Welcome to Band Jury, a SPIN series in which artists defend black sheep albums they feel deserve another listen. These are projects that, for whatever reason (middling sales, negative reviews, a misunderstood stylistic shift) have fallen slightly out of fashion — or perhaps never reached it to begin with.

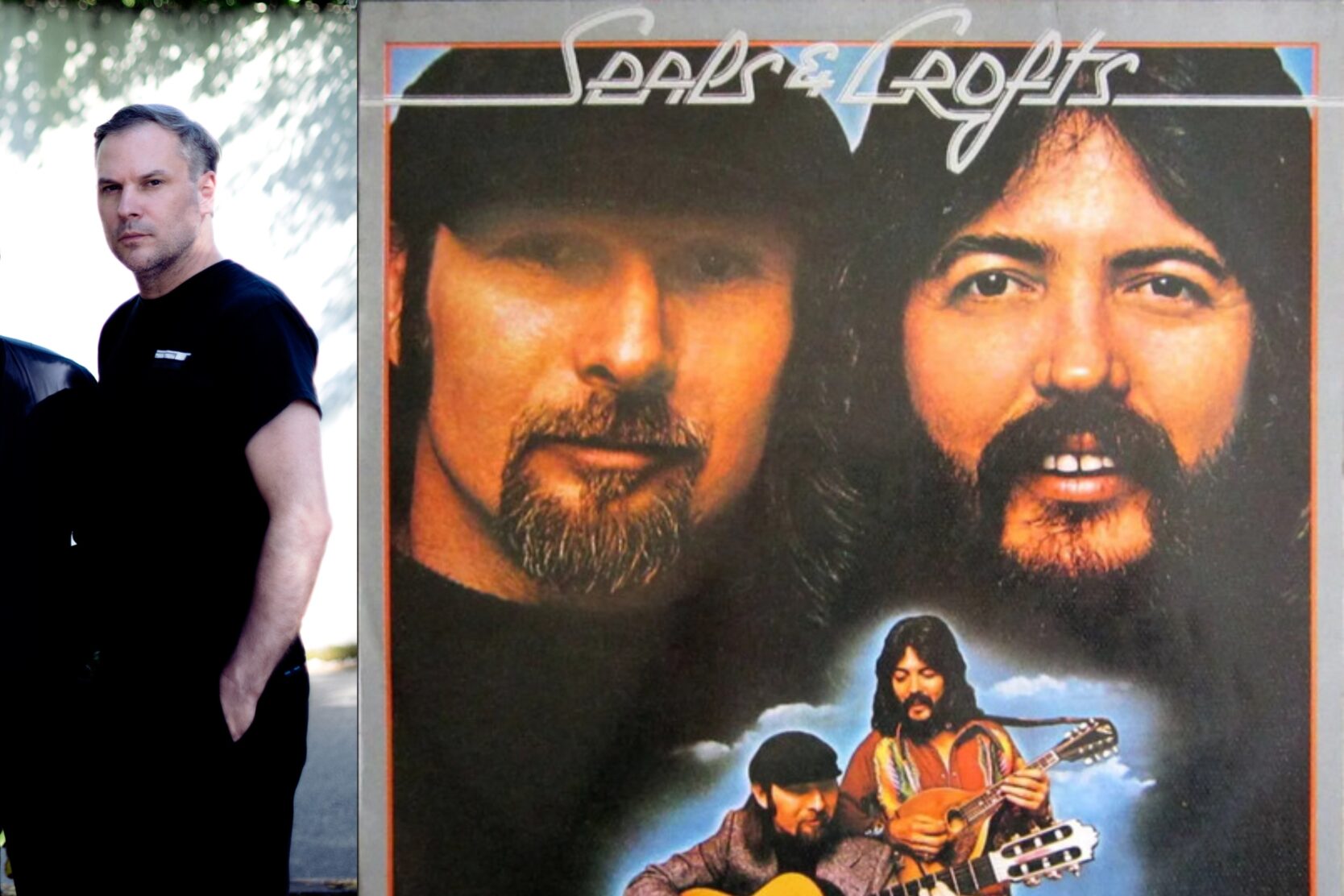

The Defender: Emil Amos

Qualifications: Genre-blurring songwriter and producer (Holy Sons); occasional podcaster and music journalist; drummer/multi-instrumentalist for multiple bands, including experimental rock quartet Grails, who released their eighth LP, Anches En Maat, in September; human who enjoys music

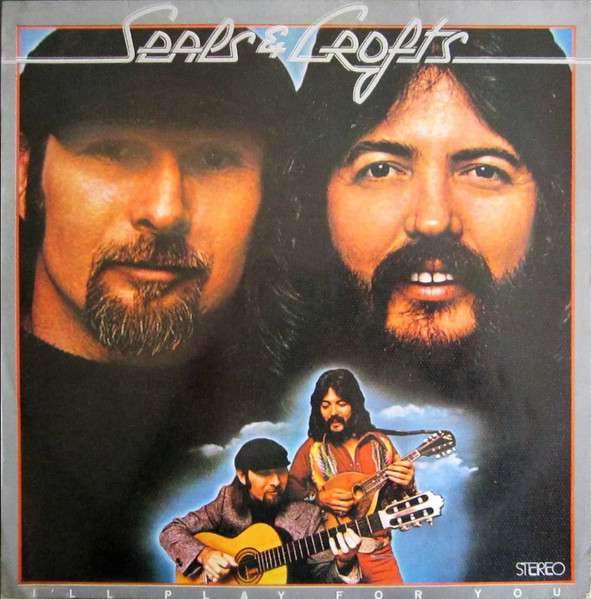

The Defended: Seals & Crofts’ 1975 album, I’ll Play for You

Overview: left little to no footprint, review-wise—not even a write-up at the generally comprehensive AllMusic; peaked at No. 30 on the Billboard 200, a modest decline after the successful run of 1972’s Summer Breeze, 1973’s Diamond Girl, and 1974’s Unborn Child; spawned two singles, “I’ll Play for You” (No. 18 on the Hot 100) and “Castles in the Sand”; earned middle-of-the-road score (3.13/5.0) on fan-review site RateYourMusic

If you consult the music-snob gospel codified in part by snarky album reviews, certain styles of music are inherently “uncool”—you might find yourself dismissing an entire genre without even exploring it, based on some kind of baked-in cultural trope you don’t fully grasp.

I experienced a variation of that scenario. As a teenager, I secretly enjoyed the mellow, melodious strains of soft-rock (like America and Bread) that I first absorbed via classic pop radio—but I didn’t allow myself to engage with it beyond the confines of a JCPenney dressing room or dentist office lobby. (At least not until years later.) I knew I’d be roasted, at least playfully, for mentioning it to a friend in conversation. But why, really? I’m not sure even the roaster would have a good answer.

Grails’ Emil Amos first started to engage with soft-rock in a real, meaningful way in the early 2000s, while “poor as fuck” and collecting 8-tracks on the cheap. After years of recording lo-fi music, he wanted to step up his production game—and he eventually learned valuable lessons from music often dismissed as sonic wallpaper.

“It was such a delightful revelation,” he tells SPIN, “that all the shit that I’d ignored held a lot more secrets and textural devices that I needed to discover.”

One such band was Seals & Crofts, who released a string of ‘70s hits (“Diamond Girl,” “Summer Breeze,” “Hummingbird”) balancing slick vocal harmony with ambitious arrangements—everything from saxophone to mandolin. And you can hear traces of that influence—along with metal, krautrock, psychedelia, and just about every other amplified genre—in Grails’ rich instrumental stew. (Amos even says there’s a “parallel to the Seals & Crofts conversation” in Grails’ latest album, Anches En Maat.)

The musician spoke to SPIN about Seals & Crofts, 1975’s I’ll Play for You, and the beauty of discovering (or re-discovering) music without preconceived notions of coolness.

“Record collecting really is reconstruing the entire narrative of music for yourself as a feat of independent thinking,” he says. “If you really want to get into why people sift and spend all this time, it appears to be nerdy, but I think it’s in an effort to find the true humanity in the creases and shut out the industry spoon-fed narrative that has crowded your field of vision for so many years.”

When did you first hear Seals & Crofts? Were you immediately a fan?

I consider myself a perpetual newcomer to Seals & Crofts, and I like to keep it that way. They embody something that I’m always curious about but don’t want to burn out, which is [partially] the extreme seriousness to their approach. Bands like Bread had a kind of fakeness, a kind of plasticity—I think Bread is one of the great American bands, but there’s something duplicitous about them. There’s something awry, something poisonous behind Bread’s repellent shell.

Seals & Crofts were a later discovery for me—their sincerity is weirdly shocking or something. I think they stand parallel to Crosby, Stills, & Nash throughout their career. The more you tighten the lens on Crosby, Stills, & Nash and accept Seals & Crofts for what they were, Crosby, Stills, & Nash starts to look like a flagship band for white-privilege music, and Seals & Crofts starts to look like a very genuine, working-class, beautiful expression. I think that’s the crux of why they’re worth investigating.

I assume, given that you were pretty committed to hardcore back in the day, that you probably didn’t immediately seek out the music from that era.

Back in the ’90s, I was such a militant lo-fi hardcore kid that, when I would experience music from the other side of the tracks, like techno, it would make me feel so gross. It sounded so foreign and so sleazy and so capitalist to my ears. But eventually, my curiosity about the other side of the tracks came full-circle. At the beginning of the 2000s, I’d moved to Portland and we were starting Grails—in my opinion, [that era] was a very global rebuilding period for underground music, which had hit a wall to some degree. The ’90s’ perceived ethics and stylistic parameters had reached the end of their road, ya know? Plus, just the commercialism of the underground had kind of spoiled a lot of what was exciting back in the Sun City Girls days. There was pretty much nothing that was risky by ’99. You saw Malkmus breaking up Pavement for good reason—there was something dead in the road, and we had to clear it.

When I would come home from work, and I was poor as fuck, I started collecting 8-tracks. I would hit the bong and flip through this forgotten music history that you could get for a quarter because everybody had abandoned it. At the start of the 2000s, I needed lessons in record production. I needed to understand how to step up from lo-fi to the world of hi-fi because I was very intimidated. I’d spent 10 years on a four-track. Grails was getting signed, and Holy Sons, my solo project, was coming out with my first record. I knew that, to enter the dialectic of music history, I better come with some fucking schooling, or else I was gonna embarrass myself.

In listening to the 8-tracks, tape after tape—and digesting the Carpenters for the first time, really, and Bread under a microscope, and America for their greatest attributes—and it was such a delightful revelation that all the shit that I’d ignored held a lot more secrets and textural devices that I needed to discover. The first time you really hear “Summer Breeze” for what it really is, outside of the culture of car commercials, it’s kind of taking things about the Band and the Beatles—the great organic bands—and really improving certain aspects. The way Seals & Crofts approach yacht-rock is much more like Morricone—like an Italian professional classical arranger. There is no fucking time wasted. There is no fat on these arrangements. The execution is so technically unreal.

It sounds like they made a pretty big impact on you as a producer.

When you want to get into the sort of depth of what they’re giving you, there’s a lot to discover there. I don’t want to burn it out, so I only put it on every once in a while, but I’m still figuring out shit about them. I just learned they were in the Champs and did the fucking song “Tequila,” which takes you back to the ’50s in Texas. If you really want to get into the science of record production, Seals & Crofts should be 101 in schools.

You specifically highlighted the album I’ll Play for You, partly in reaction to a quote from your buddy Lou Barlow. In a 2017 Facebook post, he wrote the following about the title track: “I totally forgot about this song…so familiar yet so truly awful, really…not because it’s cheesy ‘70s crap, I love cheesy ‘70s crap…this just straight up sucks.”

I probably only thought to choose them because Lou Barlow is a buddy of mine and we’re putting together a compilation of his great early works right now. He posted that I’ll Play for You” was literally the worst song ever written or something. I thought, “Well, clearly they’re hated.” Then I put it on, and I actually like that song because it’s so foreign to me. Lou’s a little older, so he experienced all the true connotations of that song culturally, whereas I’m fully removed from it, so it just sounds like a funny Epcot Center escapade to me. The song actually has great production; it’s super bizarre.

As I sort of walked through my house stoned over the years, I slowly realized that the rest of that [first] side is probably one of the best sides of the ’70s. I think if you need a conversion track, “Golden Rainbow” is the song to play for people. I know it because I just did it—I played it for Grails in the van while driving from Estonia to Latvia. You could see in their eyes that they understood Seals & Crofts for the first time. They heard the classical guitars in perfect meter. The mixing is immaculate. There’s still this kind of burnout purity that makes you feel like it’s perfect comedown music. It’s there to help you, to rescue you. It’s good for you. That’s a more mature take on life and records, right? You don’t want to just hear someone making a bunch of fucking noise. You want someone to have a reason why they’re providing you with this.

It’s functional.

Right. I think the rest of the side presents a vivid picture of their contradiction. They are at work—they’re businessmen—but they treat the business with respect, like a fucking gunslinger. They approach their harmonies and guitar parts like no-nonsense Clint Eastwood. Listening to records and talking to other people can be really crazy-making—it’s like a game of Rashomon. There’s something about Seals & Crofts that seems to elude people’s ears. Anna at Temporary Residence was like, “You should do The Eagles [for Band Jury]!” She knows that I grew up kind of appreciating them in the ’90s that other people had difficulty with.

Going to Boston and kind of trolling around in the underworld and doing hard drugs and stuff, I came to a great revelation that the music of the streets and the music and heroin addicts and Vietnam vets and the music in the homeless shelters that I’ve worked in is the Eagles and Seals & Crofts. That’s the music people OD to—it’s not Aphex Twin. I just got really sick of the kind of pretender culture that likes to take drug experience and throw it into trendy corridors. For me, it was like, “Oh, I’m really touching the Earth’s soil. I’m really there and seeing the music of the disenfranchised.” That was a great revelation to me. But also, as a day and night practitioner of songwriting and arrangement, my perspective on the Eagles is just inherently different from everybody else. What I’m trying to pick up is what they’re good at. Everybody else is just trying to rehash some dumbass Lebowski line.

As a musician, you’re interested in this music in a different way than some wiseass cracking jokes about the album covers. You want to look under the hood a bit.

It’s easy to feel like an outsider in your own culture when indie-rock has largely been the sound of white privilege, when indie-rock has been the sound of boring people being bored and offering some sort of legitimization of that worldview to their bored audience. It forced people like us to go back and find a more complex picture.