In 2009, I set out to launch a music-based mobile application. The iPhone App Store had just launched in 2008, and there was a palpable sense of potential in the air. I had always had a love affair with technology and music, and this was an opportunity to marry the two in a new medium.

Negotiations with T-Pain’s team commenced, but things didn’t work out. Undeterred, they went on to develop a groundbreaking product, cleverly collaborating with Antares, the creators of Auto-Tune. My partners and I had the good fortune to team up with Interscope, specifically Troy Carter and Bobby Campbell. Our combined efforts gave birth to an innovative karaoke app featuring Lady Gaga.

This was the first time an app had real artists’ masters that you could use for karaoke. It had social features and gaming. You could actually sell catalogs from other labels out of the app. The purpose of this is not to reminisce but rather to provide context for an experience that ultimately served as a crash course in music licensing.

There were multiple moments during my app development when the deal almost fell apart. If not for Lisa Rogell, who was serving as counsel at Interscope, Rand Hoffman might have crushed the deal. In those days, the natural response from labels was simply “NO.” From Business Affairs, it was an even sterner “NO.”

With that experience under my belt, I always kept a watchful eye on the companies that raised outside money and built interesting music offerings. Too often, because they did not calculate in the complexity of music licensing, they went out of business, or were sued and could not survive. Fighting a lawsuit for a startup is virtually impossible. Ultimately, the companies that made it were ones with deep funding, enough traction, or that worked with the labels early enough to clear the licenses.

However, when it came to traction, there was an interesting, even paradoxical, dynamic at play. If an app was infringing copyrights but had managed to attract millions of users, the industry often turned a blind eye, at least temporarily.

This was likely due to the potential for negotiations, given the app’s evident popularity and revenue prospects. Conversely, a similar app, infringing copyrights but with no substantial user base, would face immediate legal consequences and likely be shut down. Without a substantial user base, these apps lacked the financial leverage needed for negotiating licenses or handling lawsuits. This stark discrepancy in outcomes based on user engagement was intriguing, to say the least.

And so, I present to you my graveyard of music startups:

MP3.COM, founded in 1997 by Michael Robertson. You could stream and download music. In 2000 the RIAA sued them. A judge ruled against them in 2001. Vivendi Universal bought them that same year. Today it doesn’t exist for music.

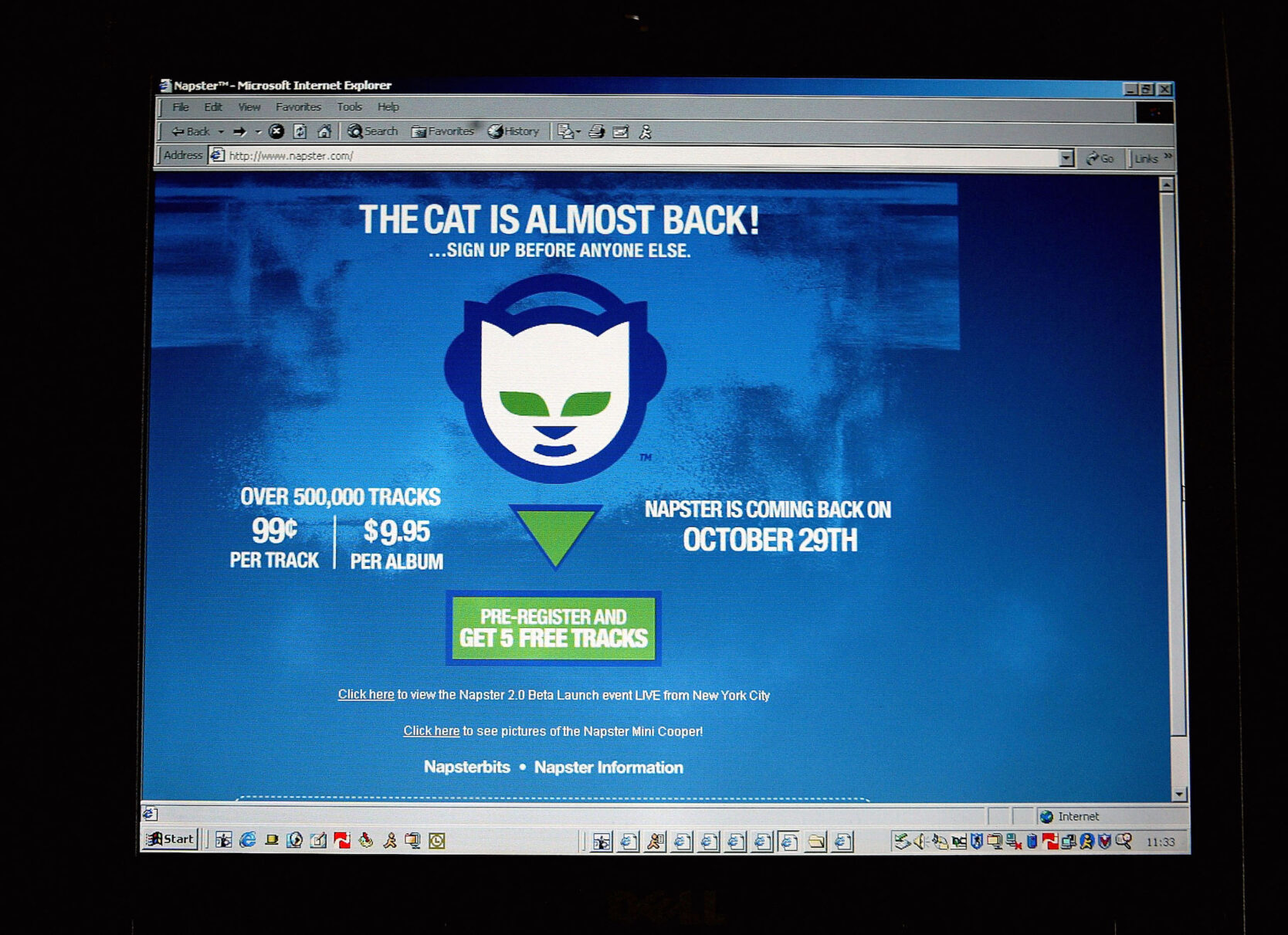

Napster, founded in 1999 by Sean Parker, Shawn Fanning, and Hugo Sáez Contreras. The RIAA sued that same year. A federal court ruled in favor of the record companies in 2001. Best Buy purchased it in 2008, but it never regained any momentum. Napster had amassed 26 million users.

Limewire, founded in 2000 by Mark Gorton. You could share and download files. The RIAA sued them in 2006. A federal court ruled against them for copyright infringement in 2010. They went out of business.

Grooveshark, founded in 2006 by Sam Tarantino, Josh Greenberg, and Andrés Barreto. They had copyright infringement problems. Universal sued them in 2011, and then several other major record companies sued them in 2015.

Beyond Oblivion, founded in 2008. They provided unlimited music to partnerships and raised $87 million. They went out of business because they could not secure the appropriate licensing and never became profitable.

RDIO, founded in 2010 by Janus Friis and Niklas Zennstrom. The competitive landscape and costs of licensing did not allow the company to flourish. Pandora bought the company in 2015.

Aurous, launched in 2015. After being sued by the RIAA, this streaming service was shut down less than two months later. Copyright infringement was the main factor.

Now for something different—companies that succeeded, or at least, kind of succeeded…

The iPod and iTunes, founded in 2001. What did Steve Jobs do differently? He transformed the music business by working closely with the labels. Apple also had a market cap of $6 billion in 2001. It was also thought that if iTunes as a music download company just broke even, the iPod would make up the margin. An iPod cost $400 in 2001.

Spotify, founded in 2006. In the beginning, Spotify struck ownership deals with the major record labels. As the company raised money, the ownership reverted back to Spotify, as record labels sold their stock. The details of advances and percentages are not disclosed. The company went public in 2018. By 2021, the record companies were completely out of Spotify. Incredibly, as the dominant force in music streaming services, the company is not profitable.

Tidal, founded in 2014. No clue if they are profitable, but the audio sounds the best due to the fact that there is no compression and is truly hi-res audio.

Pandora, founded in 2000 by Tim Westergren, Jon Kraft, and Will Glaser. They took a different approach to licensing, much like how radio works. They sold to Sirius in 2019.

To be clear, I do not believe companies should infringe on licenses. The deals made between artists and record companies should be honored. Much investment goes into the creation of a record — the heart and soul of an artist, the production, the teams behind it, the touring, the marketing, the launch — and an outside company shouldn’t get a free ride on the years of hard work that these artists and (I say this with salt in my mouth) record executives endure.

But did the record companies and all of the advisors around artists miss something here? Why is it a zero-sum game? How do you launch a business at scale with unfair economics? Tech developers love music, as evidenced by their imaginative solutions making the delivery of it so much better. Why has there not been a deeper collaboration?

This is where it changes. This new generation doesn’t seem to hold the idea of ownership and copyrights like a weapon to be used for leverage. These creators believe in collaboration. So I, for one, hope for a change as new ideas emerge.

The speed of tech development will not slow down. The question is, will the gatekeepers of the licenses allow development to happen? This may not even matter, perhaps future generations of artists will not need the support of a label in the same way and will allow the music to be shared, not unlike the way cassette tapes were passed around at Grateful Dead shows. Except it will not be an old technology, it will sound better, be delivered faster, and used in innovative ways we have never imagined.

Les Borsai is co-founder of Wave Digital Assets