Mention rock music and doctoring together, and the conversation inevitably rolls into tales of excess and the outright weird; non virtuous groupies waving priapic urethane devices at neanderthal roadies in a bid to get on THE PLANE, where toward the rear will lurk some devious spiv with a medical degree and a Gladstone bag packed with long outlawed barbiturates, pharmaceutical Merck cocaine, and a variety of chemicals usually reserved for thoracic surgery on rhinos. Just for effect, he’ll be the one looking like a candidate for doing a nickel in the Betty Ford Clinic.

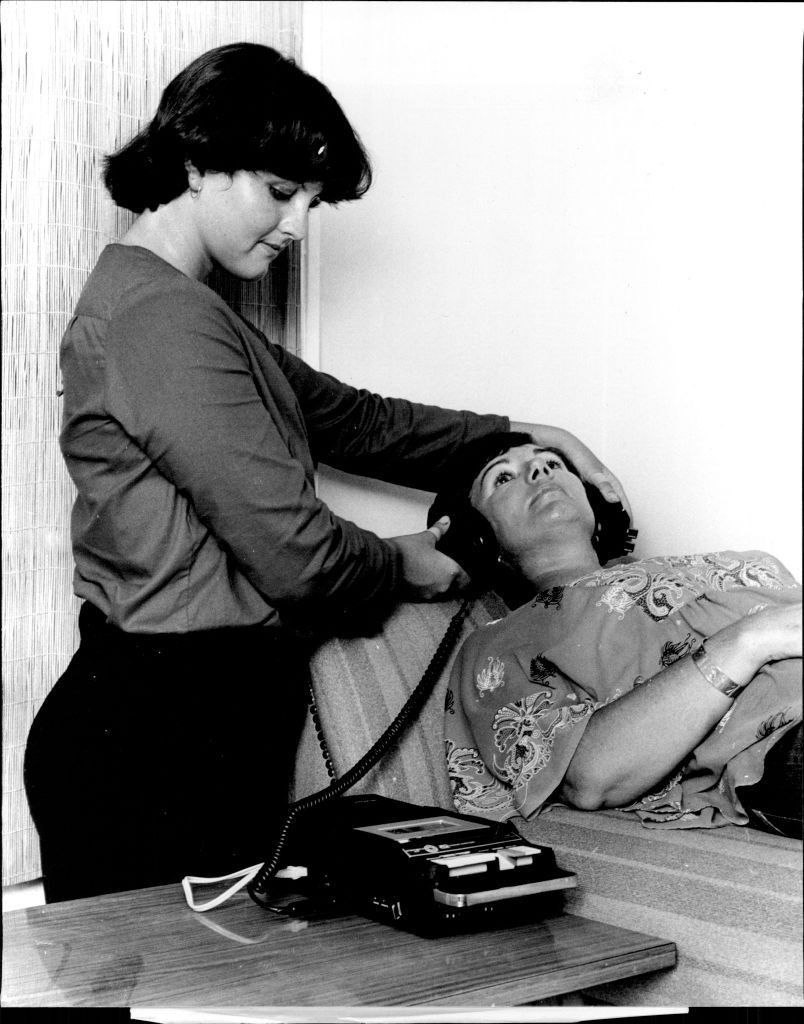

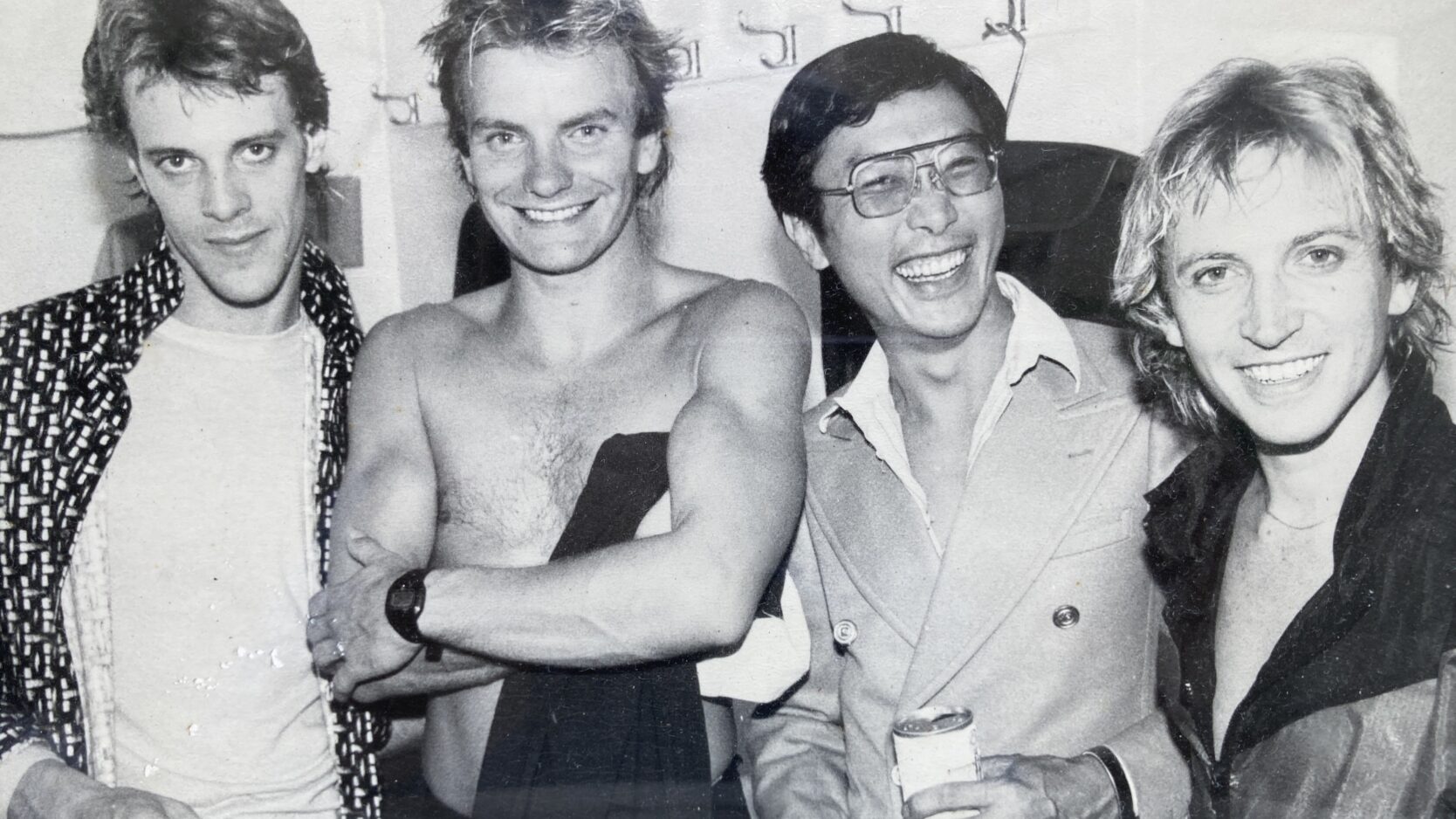

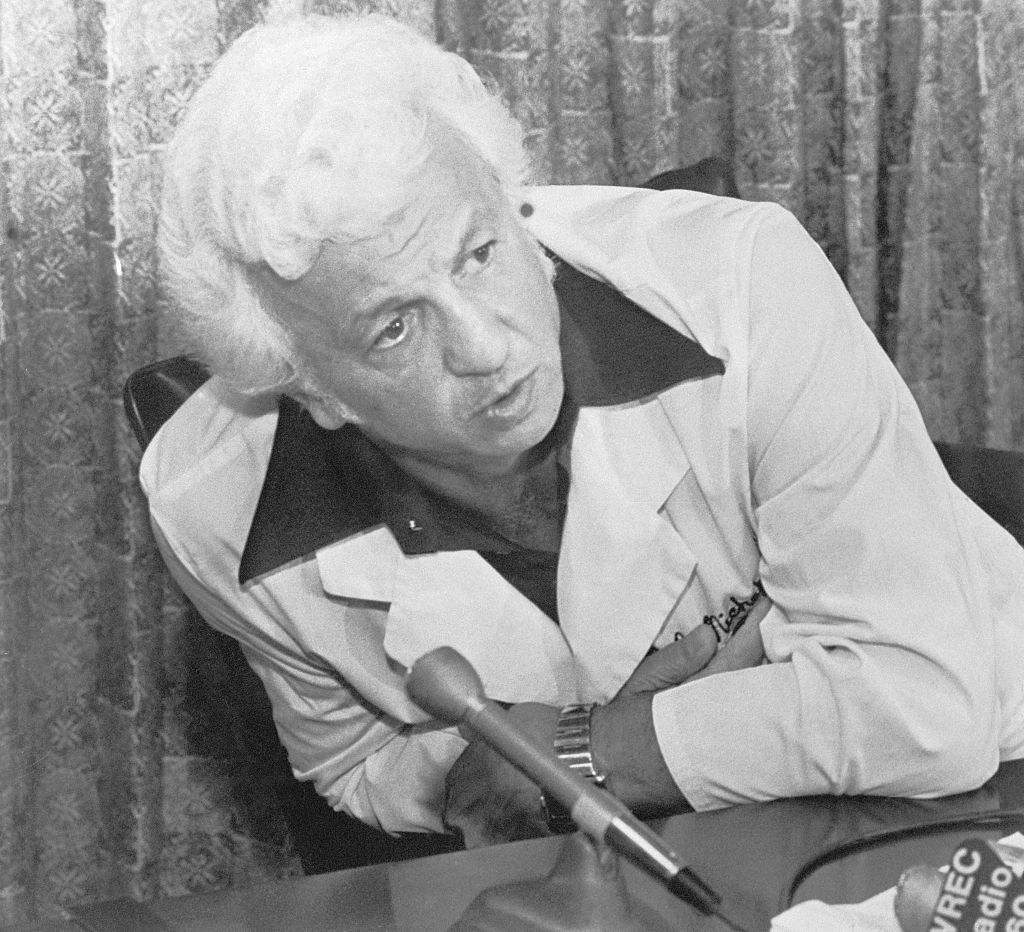

But not Ian Chung MD. For five decades this Hong Kong-born, Sydney-based doctor to touring stars has looked after the likes of Tina Turner, the Police, Johnny Cash, Janet Jackson, P!NK … you name ‘em, he’s probably helped ‘em — occasionally to the chagrin of certain artist’s fans when he has pulled the plug on their concert for health reasons (“That’s it. You need to cancel.”) Anyone after some go-to Dr Feelgood like Elvis’ Dr Nick can forget about this guy. Chung, who is a primary care physician with a Masters in Psychiatry, combines a variety of holistic disciplines, particularly hypnosis, and eschews prescribing any drugs of addiction.

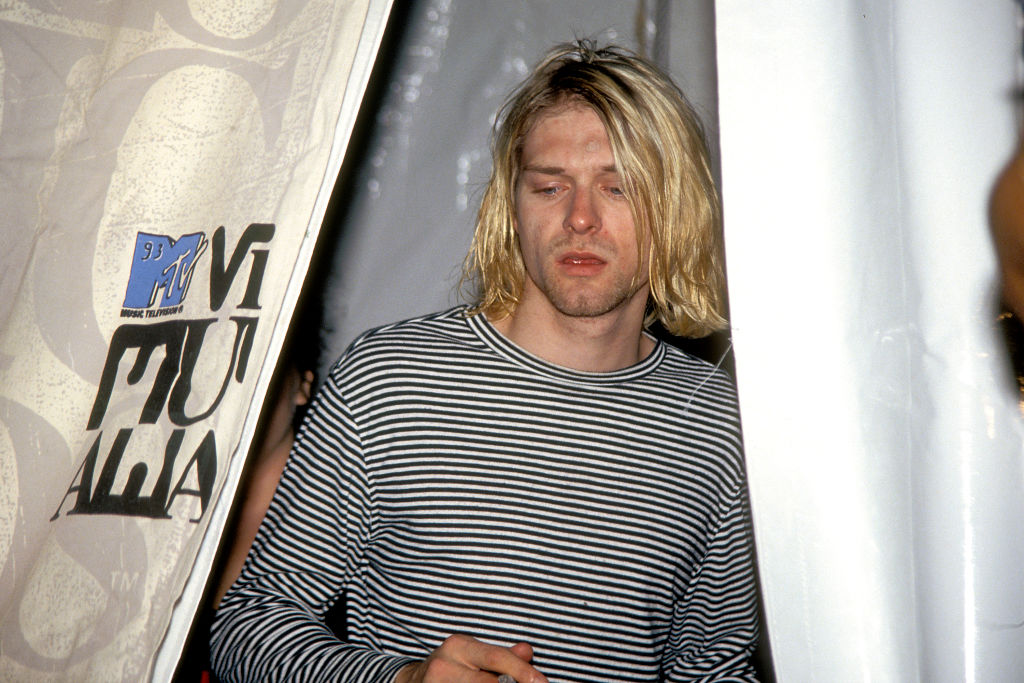

Like another of his charges, Mick Jagger, (whom Chung is six years older than) he is in obscenely rude health. When he sits down with SPIN he places a copy of Bono’s recent autobiography Surrender on the table, which namedrops Chung (Kurt Cobain also mentions seeing the good doctor in his journals, although without naming him). On one of U2’s umpteen world tours, Bono started getting sporadic tightness in his chest, even while jogging. Chung’s diagnosis led U2 to postponing three gigs. Turns out Dublin’s number one son, social activist and rock god philanthropist also had a fear of meeting people. I mean, Bono. Who’da thunk?

“There are some bits that he doesn’t write about, so I won’t reveal those – obviously for confidentiality reasons,” Chung says, tapping his finger on the tome, but without a stethoscope. “However, because of that, we ended up canceling three concerts. And one of the things that I said was that the funny thing is if you sing, you won’t be at your best because your voice is not right. And people will not say “Isn’t he wonderful!” He came, even though he was sick, then they’ll say, “Oh, he’s not quite as good as we thought he was.”

Also Read

Kurt Cobain Forever

Chung is reluctant to discuss individuals, although he did feel it okay to talk about the first—and only time—he came near smoking weed.

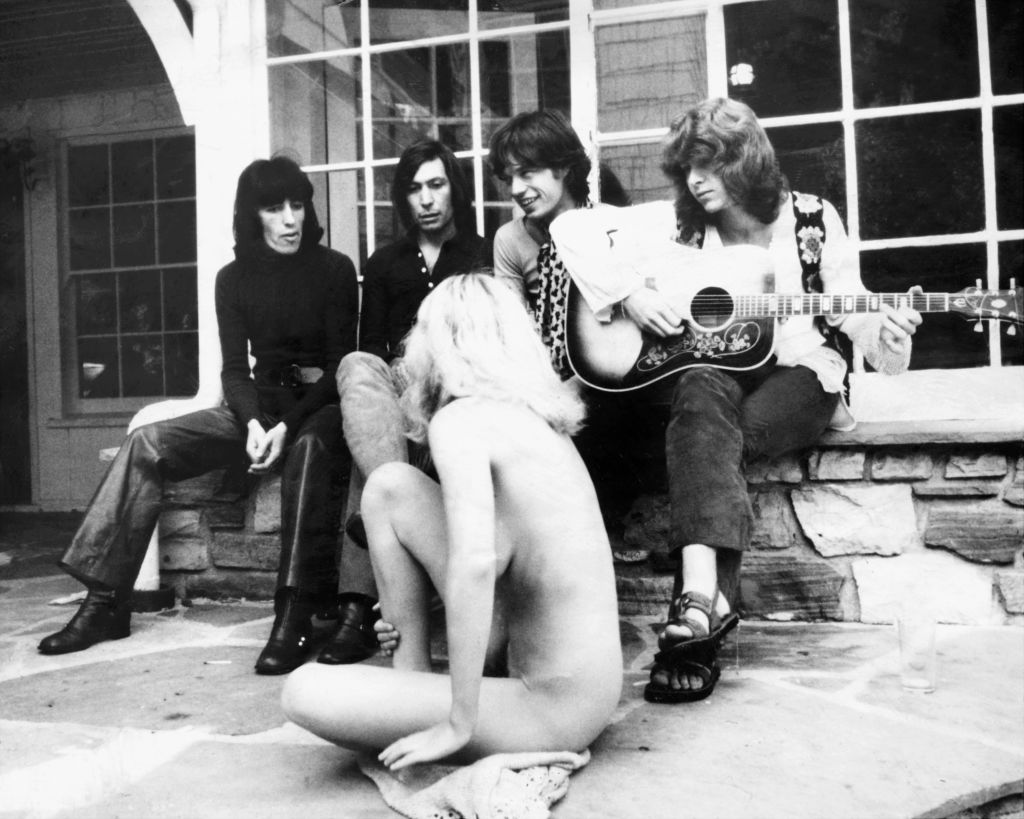

“I’m touring with the Stones and one day we’re laying about resting, and Keith says, “Hey doc, come and have a joint.” And I say I’ve never had one, and he replies “you’ve never had a joint?” I say “I wouldn’t know what to do.” So Keith tried to teach Ian Chung how to smoke a joint — without any success. He and the saxophone player (Bobby Keyes) were doing this thing called a ‘shotgun’ with a rolled up paper and I …” Chung rolls his eyes and gives a wry grin. “ Well, it just didn’t work.”

SPIN: How can musicians get into a healthy way of living when the lifestyle pushes the opposite way?

Ian Chung: They have to realize that it is for their benefit. Not just for their health and longevity, but even for their performance.

Over time I have come to recognize the bands that will—behaviorally and lifestyle-wise—make it healthily through a world tour and those who won’t.

You have to manage your pre-performance preparation and the post-show come-down. That’s fundamental. Those ones who don’t know that—who decide they’ll party on afterwards—well, it gets ridiculous.

When I was touring with the Stones we had a life between shows, and not the wild parties that people might have thought. We’d go to a really nice restaurant, maybe 10, 20 of us. And we’d have a really pleasant night. Very little wine consumed. Or we’d rent out a theater, and we’d go to the movies. A lot of us. And after the concerts, we went back to the hotel. Sure there were drug dealers following, but all they managed to sell was a bit of cannabis. So they get to hang around a bit. Maybe a couple of girls and maybe a couple of dealers, but it wasn’t like a ranting party.

How would you treat an artist with a pronounced drug problem on the eve of a major tour?

The first thing is to assess the situation. What is their state? You have to understand the problem in great detail. What actually are they like? What’s their mental state? What’s their emotional state? What’s their physical state? And that leads us to a solution.

In some instances, I may have to say, “That’s it. You need to cancel.”

And at one extreme end that’s what it may have to be, but that only happens after I’ve done an adequate assessment. I mean, if your car’s not going right, what do you do? You have to do a proper, full assessment. You don’t just say, oh, change the petrol [gasoline].

You could start with that, but this is an emergency. It may be, “Look, let’s not just fill you up with heroin. Let’s try something else that might just get you there.”

But realize that this is not going to be what people might expect of you. And you then have to decide is it worth it to go on and give people less than they expected?

I have to assess what their current state of drug use is, and to what extent, and all the things that relate to that. What range of drugs? What frequency? Is it intermittent? Is it constant? How much is it impacting their lives?

I spend quite a few sessions with them. I won’t know that after just one. Let’s take something as simple as smoking. “What age did you start? Did your parents smoke? How much do you smoke? Have you tried to stop before? What methods did you try? How well did they go? Oh, you’ve had hypnosis. What happened?” Et cetera. And so it goes on until you actually know.

I don’t want to replicate what didn’t work before: hypnosis, patches, or whatever else. That’s not to say they don’t work. Maybe they just weren’t used the right way. I mean, there is hypnosis and there is hypnosis. Some people know how to do it and some don’t. So until you have an adequate, full assessment of the problem and where the current status is, you don’t know where to go.

Once you know that, then you’ve picked the point where you can enter into resolving the problem. And it may be this day they’re ready and committed to get on with it. They’ve done two, three detoxes—which haven’t worked—but this time they’re sick of being sick. They’re ready now to go into detox and take it seriously. Maybe they’re near dead.

Or they may be “Oh, detox? No, no. I could do it on my own.”

How can you start anywhere without knowing these fundamental, attitudinal things?

Is there any root cause for musicians getting addicted to drugs?

There’s no single root cause to anything.

And in terms of musicians, multiple factors concentrate what exists throughout society.

There is an aspect of it [drug abuse] that is fashionable — good publicity, maybe. With some, it helped their image.

But it is also a fact that there is a certain level of performance anxiety for everybody. For some it’s extreme and they need to take something before every performance.

If you are about to perform, there’s anticipation, or it could just be excitement — but it can feel like anxiety, and then you may use the wrong method for dealing with it.

Another factor is that being a musician can be a very insecure life. And that life creates other forms of insecurities: in relationships for example.

It’s very complex and it can be existential, meaning that their sense of direction is not clear. A lot of musicians don’t really know where life is going, or what style of music they should do, or what teacher they should use, or who they should team up with, or where they’re going to live, or even what they’re going to have for dinner.

The musician’s life is not for everyone.

What are the main health challenges musicians face?

It’s broad and connected with a multiplicity of things like the type of lifestyle they’re having to live. So therefore having an ability to comply with the circadian cycle; how do you do that? Your gig doesn’t finish till, say midnight, and then there’s a wind-down period. So how do you then get into the circadian cycle after it?

A lot of musicians have no idea that it’s a necessary thing, so what they do is to use drugs for the wind down. Well, that’s not very helpful. Having a healthy diet is important for your mental health and your physical health. But they may not have either the nouse or the time or inclination. Added to this is a sleep problem, an element of stress, and maybe some drug and alcohol use.

Multiple factors.

You have a great reputation for helping singers that are having problems with their voice. What’s your approach?

Well for an ENT [ear, nose, and throat] doctor, they would be saying, “Let’s look at the vocal cords and see if they’re inflamed or swollen” and so on; that’s their focus.

If for some reason somebody got to the point of thinking [that] maybe it’s psychological — maybe because he’s been on the road so long he’s anxious, the psychiatrist would then look at his psyche.

I am aware of anxieties, so I would be assessing that along the way, but my approach would be firstly to make sure there’s nothing wrong with his throat. Because I don’t want [to miss] anything physically wrong and have that damage [go untreated].

The thing I’d be aware of most of all is the fact that he’s been on the road for 12 months. Those vocal cords have got to be tired.

And number two, he’s been in hotels for 12 months and been in all parts of the world. He would be in an air-conditioned room all night long, which dries out his throat. Then he’d go out into whatever atmosphere—could be anywhere—a place where it’s snowing or where it’s a heat wave. That is going to affect his throat. Therefore, I take a holistic approach to the throat. It could be physical, medical, it could be psychological; he’s fit, but it could be just the way he’s living his life.

That’s my approach to all things. Don’t have this narrow, mono-therapy attitude towards things [and towards] fixing them. Usually multiple things are contributing. And if I don’t address several of them, it’s not going to fix it.