We are somewhere around Detroit on the edge of the jazz scene when the psychedelic macrodose begins to take hold. Tupac Shakur asks Tim Roth something like “ever felt your luck’s running out” and suddenly a friend beside me thrashes in his seat and the cinema’s full of people staring at us, all stink-eyes and muttering, even as the movie is racing off the screen about a hundred miles an hour with the lights flashing. And a voice screams, “This is happening!”

Then it’s quiet again. My buddy has curled forward to claw at his jeans. “It’s all real,” he hisses, staring at a spumy sea of spilled popcorn with his eyes clenched shut. “This is real.”

“Yeah – and?” I say. “So let’s keep it together.” I schlurp my drink—can’t work out if it’s hot or cold—smile at the stink-eyers in front, exchange crazed grins and knee squeezes with my girlfriend, and swivel my head back to the front.

No point telling my buddy that Tupac – the shiny bald dude dazzling us here in a cinema one winter’s day on the west coast of Australia – was thrown out of reality some months back by a gunman in a white Cadillac who pulled up beside Tupac at the Vegas intersection of East Flamingo and Koval, and shot him four times. Took him six days to die. Tupac never even saw this flick.

Yet here we are in his rippling room, his space, on stage with him and Roth and Thandiwe Newton as they flow from a strung-out caper of narco-need and crime into a beautiful fusion of hip hop and jazz.

I spay my palms to better take in the energy of this dead man as he raps:

Life is too short, I feel trapped

Hoping I don’t get caught, watch my back

Lost in the traffic, heartless and tragic

Don’t wanna get my ass kicked

So I walk in this mindless state, and this dope make me feel this way

I tell yaLife is a traffic jam, I’m stuck

Life is a Traffic Jam, from “Gridlock’d”

When will you realize you’re fucked?

Don’t try to change my ways, I’m hopeless

Victim to the games we play, stay focused

Watch for the crazy ride, don’t lie

High ’til the day we die

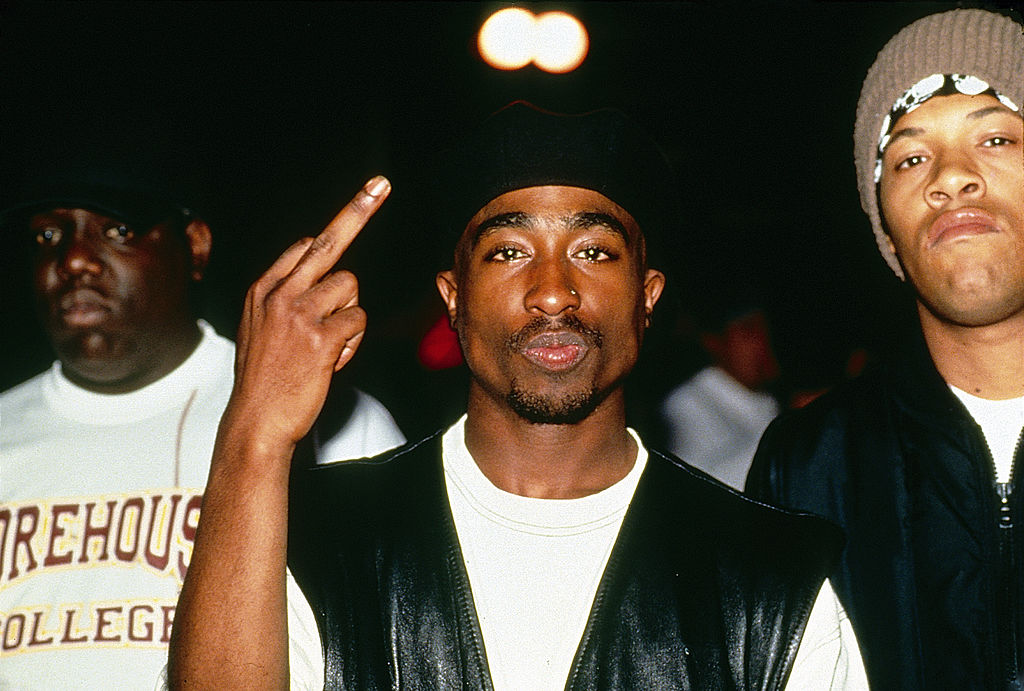

A quarter of a century and change later, with the macrodose having tapered off, I call Tim Roth to ask what it was like getting to know his ill-fated co-star. Then I ring director Allen Hughes, who shot music videos for the man but then copped a beating by Tupac’s goons after he fired the rapper from the landmark 1993 flick, Menace II Society, but who this year released Dear Mama, a deeply insightful yet gracious five-part documentary about Tupac and his late mother, Afeni Shakur.

Let’s start with Roth, a distinctive English actor born in 1961 who had settled in the U.S. after the success of his second American film, Quentin Tarantino’s Reservoir Dogs (1992) opened more doors for him.

TIM ROTH ON TUPAC SHAKUR

SPIN: Before making Gridlock’d, had Tupac Shakur ever come across your radar?

Tim Roth: No. My ignorance was extraordinary at that time. I had some concept of hip hop music and rapping and rappers, but my background was in reggae and ska, having gone to school in a predominantly Black [Jamaican and other West Indian] school in a Black neighborhood in South London. So I was brought up with that music: with Peter Tosh, Lee Scratch Perry, and obviously Bob Marley. And then with the punk movement, which had its roots in reggae and ska – the Clash and bands like that.

I was MC at a huge free concert in London [Artists Against Apartheid, 1986], which Big Audio Dynamite were playing, as well as Boy George, Sade, even Sting. I was the guy that was announcing the bands and telling you where you could find your lost children and where the toilets were. So I was there all day. I love shit like that.

So I remember Gil Scott Heron there. He came from the airport, got outta the car, went up the stairs, onto the stage, did his act, did his stuff, and then turned around and went back the same way – with a newspaper tucked in his back pocket. He was about as cool as it got. We were all blown by him. He was incredible.

By the time I came to America hip hop obviously had a solid foothold on the music scene, but Tupac wasn’t on my radar – which is pathetic if I think about it. But it was a different world: cell phones weren’t available, and the internet was in its very early stages – so you listened to radio and you bought albums, you bought CDs.

I didn’t know much about hip hop when I first came here. My wife had me listen to some music but I just wanted to make some movies and get the fuck out. That was my mantra really. I wanted to go home to the UK. I was lonely. I was a bit scared by the whole thing. But I knew that I had to do it because I wanted to be an actor. So you have a shot at it over here, and then you go home: that was basically how I thought of it.

So I came straight from Australia, where I did a not very good movie [Backsliding, 1991] and did a film called Jumpin’ at the Boneyard in the Bronx. Then I came down here to California, thought I’ll have a crack at this, and then I can get on a plane and go home.

I had an agent at the time, which I got through working with Robert Altman [Roth played Vincent van Gogh in Altman’s Vincent and Theo, 1990]. So I gave it a go. And what happened was I got employed, and not only that, but it was the beginning of the independent film thing. So I got employed in things I wanted to be in. It was fascinating. I didn’t have much of an overhead. I had a little flat and I just made films, and the second one was Reservoir Dogs. When that hit, everything changed. Independent film was what I always wanted to do. I didn’t want to be a movie star. I wanted to be an actor.

Being in the independent film world and working with new directors and first-time directors on new kinds of projects was what would give me longevity as an actor – and that’s what I wanted to be for the rest of my life. It’s the only thing I’m vaguely qualif- … well, I’m not even qualified in it, actually.

Anyway, when Gridlock’d came along I read the script, and it was an independent film – which appealed to me. There was an aspect of it I thought, meh, about, but overall, I thought the characters were funny, it was smart, it was interesting, and the story was worth a shot. And it’s this young director: Vondie Curtis-Hall, so I thought okay, let’s have a go. This looks good.

It was also out to Laurence Fishburne at the time, but he had done a long run on a play that involved drugs and addiction [as Gridlock’d does], so he backed away from it in the end. I was very keen on working with Laurence, so I was like ‘oh’. And we were back to square one.

Then the director gave me a call and said, “Listen, there’s this rapper, Tupac …”

I was like, “You can stop right there. I need an actor who’s got some fucking chops to do this And it’s comedy, which is even harder. Serious [comedic] timing is going to be needed if we’re going to pull this off.”

And Vondie says, “Just trust me on this.”

But I didn’t know who this guy—Tupac—was. I guess I’d driven past the billboards where it said Double Platinum on Sunset, and hadn’t been paying attention to this beautiful human that was looking down at me. Anyway, the director persuaded me, he said, “Listen, why don’t you just meet him?”

There was this little restaurant that me and my wife used to go to. It’s gone now, but it had a lovely terrace out the back that you could sit out, out back, and it had little corners. So I thought it’d be good to sit in a little corner and have a chat with this guy. So I got there at this restaurant, which was always a busy place, but I went through and it was empty – except for the director sitting at a table in the corner.

We sat and chatted for a minute, waiting for Tupac to show up. Then in came some security guys and did a sweep and went out. And then in came some women and they sat in the corner across the way, and then the security again, and then they went out, and then in walks Pac. And he sits down. And I’m ready to go, “Look, I really, you know, um … I really feel that I need an actor.”

Of course he’d done that. He’d been in movies before. But you know … Anyway, he’d trained more as an actor than I had. So anyway he sits down, and within a minute we’ve got a beer in front of us, and it’s like we’ve known each other forever. We’re chatting and talking and talking, and talking character – which is much more important to me. And he’s telling me about what he thinks, how he thinks the character is, how it should be played out, where it comes from, blah, blah, blah. All of that. We were interconnecting. The meeting goes on: goes on too long. It’s fantastic.

Then gets up with his guys; they all leave. And I’m sitting there and I took, I turned to Vondie and went, “Oh, yes, please.”

Then I get up to leave and I realize Tupac has just auditioned, which is the most idiotic concept, the idea of he auditioned – and not only that: he blew it out the water, but I felt that, and we talked about it later, that he obviously this pasty face London oic is sitting there. And he felt, “Well, I better let him know that I can do the job.” And he sure. He sure did. It was extraordinary, I don’t think I could ever have done the audition as good as the one he put out there – I’m terrible at auditions.

That began our adventure. He was good. He was good at what he did. He was a very good actor. It is a fucking shame that we didn’t get to see what he could’ve done.

In Allen Hughes’ doco, Dear Mama, you say Gridlock’d was the only movie set you’d been on that needed security. Did Tupac have enemies turning up?

We couldn’t afford to shoot in Detroit, which is where it was originally supposed to be – I think because of the director’s background [Curtis-Hall is from Detroit]. So we shot in downtown L.A. It was pretty rough; we were shooting in alleyways and stuff and you had to be careful.

They had that East Coast-West Coast situation which you had to be careful of. We would have crowds of opponents at certain locations. So you had to be very, very careful with that. I mean, he [Tupac] had his team and he would arrive very carefully. If there’s weaponry around, you wanna be—this being the States and all—you wanna be careful. So care was taken.

America seems so unstable – so unfixed.

Which I think gives it such an extraordinary flavor. And it’s vast. Around the time of Gridlock’d, I did freight trains across the States, and hitched. And one of the nicest things I’ve done with my boys is go coast to coast, driving coast to coast. I’ve done it a few times on my own and with them, and taken a long way – a long route.

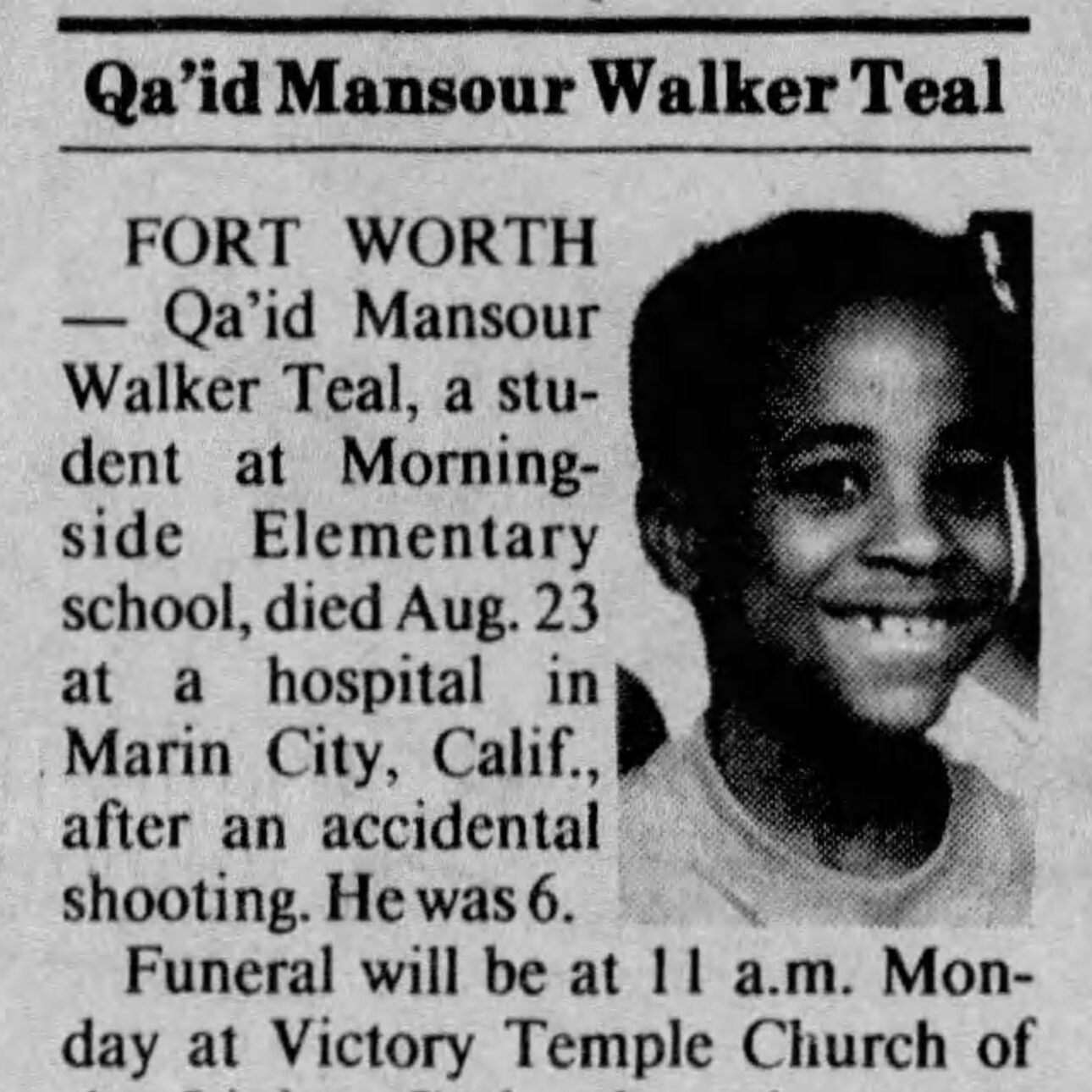

What about the various accusations and charges and convictions against him over time. Like the six year old kid who got shot and killed with Tupac’s gun when Tupac pulled a gun during a brawl. Like the gang rape allegations and conviction for sexual assault. Did he seem like a guy who might have multiple sides that you wouldn’t know anything about?

I don’t know. I mean, I only saw the one side of him. I remember … um. I don’t … I don’t. I mean, I don’t know. I don’t wanna get tabloidy on it.

Well, I’m trying to get a sense of how complicated he came across as.

I think he was a … I think he was … you know, yes, I think he was complicated, and I think he was an artist and he was brilliant. Um. I don’t know about that stuff.

I mean, I worked with him unexpectedly, very unexpectedly, in this bizarre little world – this little film world. This tiny film world. I only saw what I was … what I got.

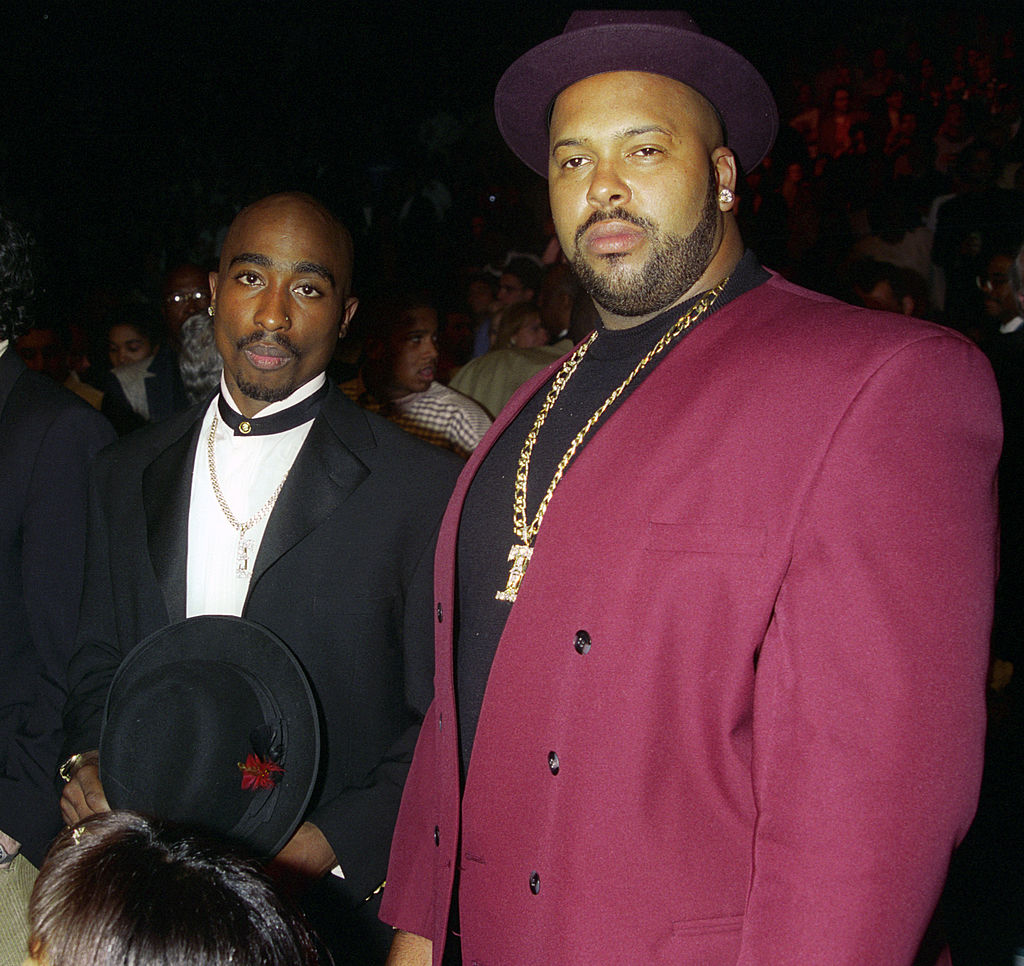

I mean, we had Suge Knight at base camp sometimes, and all of that stuff. I got to see and steer clear of him.

How did you find out that Tupac had been killed?

[First let me say:] I remember sitting with him, talking, and he helped a guy. There was a guy who’d been shot up [and was] walking across the bridge towards us in downtown L.A.. He was covered in blood. Tupac went and got him off the bridge, and got the medics in.

This guy had been shot five times. And Tupac was joking with him. He said, “Well, you got one more on me.”

We would sit; we would sit together. And I remember saying to him, “What are you going to do with all this? You know: the weaponry that has invaded – the gun thing?” We’d talk about that for ages.

But he just said: “There’s a bullet with my name on it. It’s coming my way.”

I said: “You’ve got to stop. You’ve got to put it … there has to be some kind of disarmament. It has to stop.”

Tupac said that while he loved the idea of it stopping, that wasn’t gonna be the case.

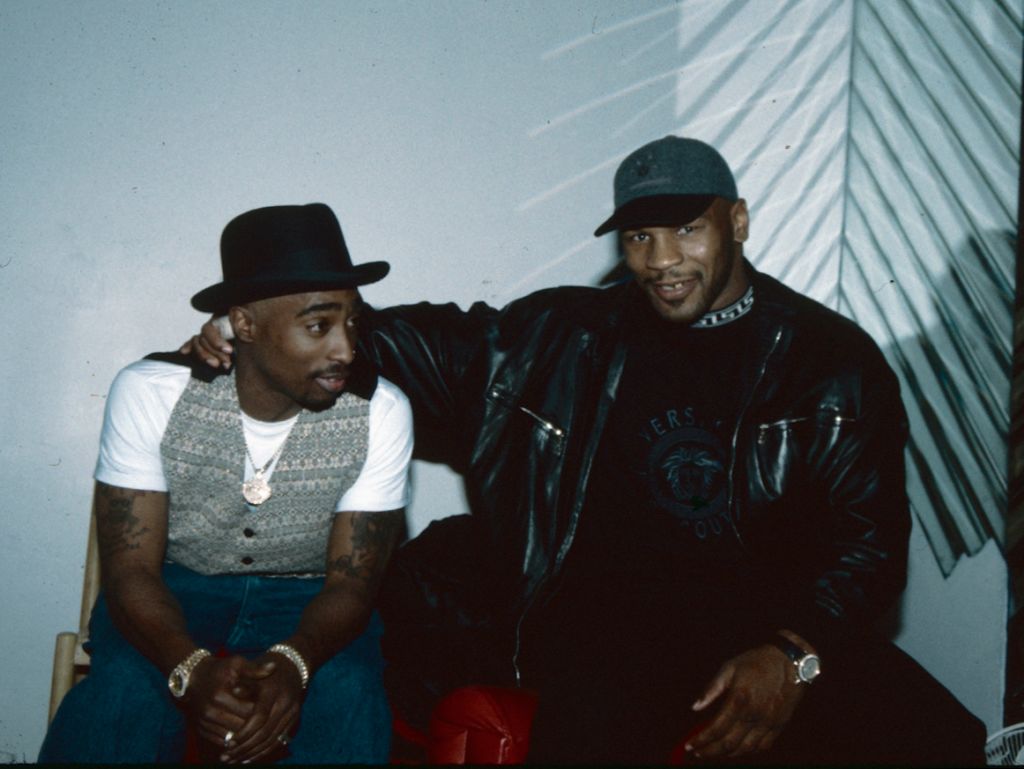

Then while they wrapped up editing, he went down to Vegas [for a heavyweight championship bout in which Mike Tyson dispatched Bruce Seldon in one minute and forty nine seconds]. We were about to do ADR [automated dialog replacement] on the film. And so we would get to see a little bit of the film. They were even thinking about showing us a rough cut, and we would get to finally spend some time together again. I was really, really looking forward to it. He was flying in from Vegas the next day, and we were gonna meet at the sound studio.

Then I remember I was in my living room at home, and the phone rang. I picked it up and it was Vondie. He said: “Pac’s been shot.”

I was like, “Is he – is he dead?”

And Vondie said no, that he’s in hospital—in surgery—that he’s out, but he’s alive.

In my brain I’m going, “Is this going to be all right?” Because we’d had long conversations about the time up in Times Square [when Shakur survived being shot in 1994]. And he’d been through a lot, that guy. Yeah. He’d shown me his scars. So I thought that he’s gonna make it – absolutely gonna make it.

They’ve taken out one of his lungs, but then they went in to get a section of the other one out, and his body just couldn’t take it anymore. We were blown away. I mean, I truly believed he was gonna survive it.

Did you have any dreams about him after he got killed?

No. I wish I had, to be honest. I do remember one of the nicest times we had – this scene: we were in the back alley and I stab him so we can get into hospital. It was a really rough back alley, but there’d been a Brad Pitt film shot in that alley, so they knew that it was possible to contain it. They hosed it all down and cleaned it out as best they could.

While we were rehearsing a very small rat, like a baby rat, scuttled across the alleyway, and Pac screeched and jumped into the air, which of course brought him much ridicule from the film crew and absolutely shut us down. We were laughing and laughing, and giving him such a hard time about it. So I saw that side of him. When we were working, all of the macho bravado stuff that was very much part of that scene he was in was gone. It just did not exist.

We lived in each other’s pockets for a time, and the idea of someone getting gunned down was alien to where I came from, you know? It was a very strange and sad circumstance.

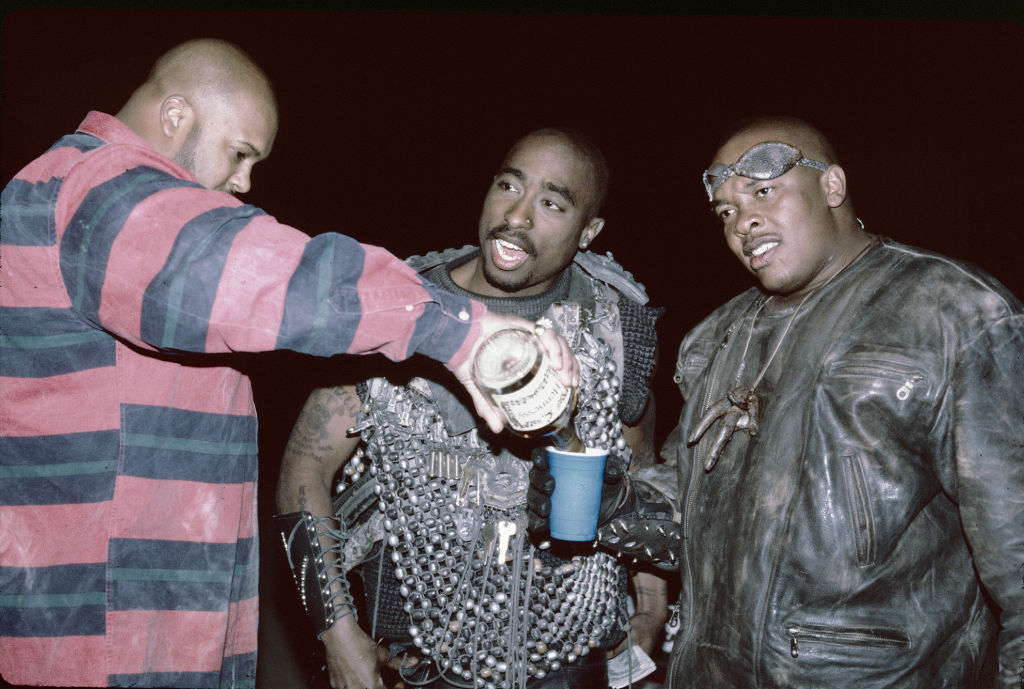

And I remember when we were filming – he was such a dick – and we were talking about Death Row Records, he said, “Let’s go down there. We’re gonna do some recording. I want you down there.” So me and him and Tandy [Thandiwe Newton] went down to Death Row. As I walked in there with Pac he was laughing his ass off.

We walked down the hallway through the doors, and people who’ve been waiting to see somebody about their music were staring at him going, “Oh my God, it’s Pac.” But they’re also looking at me going: “There’s a little white guy.”

He was crying with laughter at it. And we went into the recording studio, and he showed me around the boards and said, “Okay, let’s rap.”

I said, “What?”

He said, “Yeah, let’s do something.” So we got up in front of the mics: me and Pac and Tandi. And started rapping together. And he was crying at how bad I was. I didn’t know what the fuck I was supposed to be doing. He laughed and laughed.

Did you meet his mother, Afeni Shakur?

When we took the film to Sundance—which was back when Sundance was different, when it was this small, peculiar festival which we all loved, and not the big craziness it is now—his mum came. And she hadn’t seen the film.

We had dinner. There was no PR. No paparazzi. None of that stuff. We were just sitting – having a bite to eat in a little restaurant. I had never met her before.

We were going over to see the film, and she hadn’t made up her mind whether she could see it or not. Eventually she decided not to. Too much. Too much to see her boy that way at that point.

I’ve been going through the grieving process recently [one of Roth’s sons died of cancer last year], and I can absolutely understand that. It’s not where you can be when it’s so raw. So we just sat and chatted.

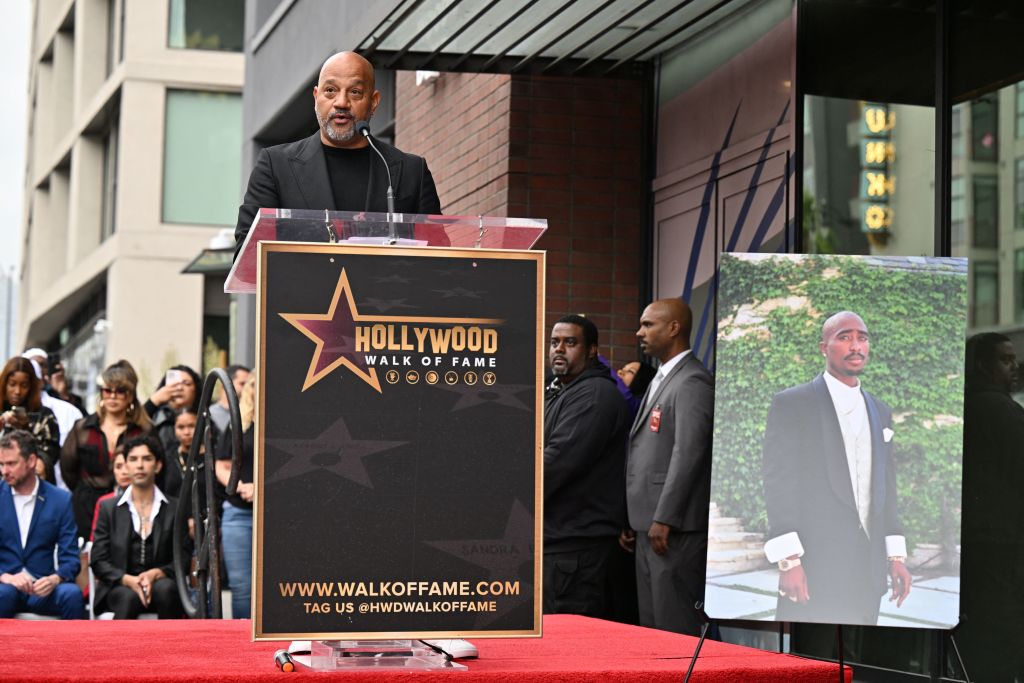

ALLEN HUGHES ON TUPAC SHAKUR

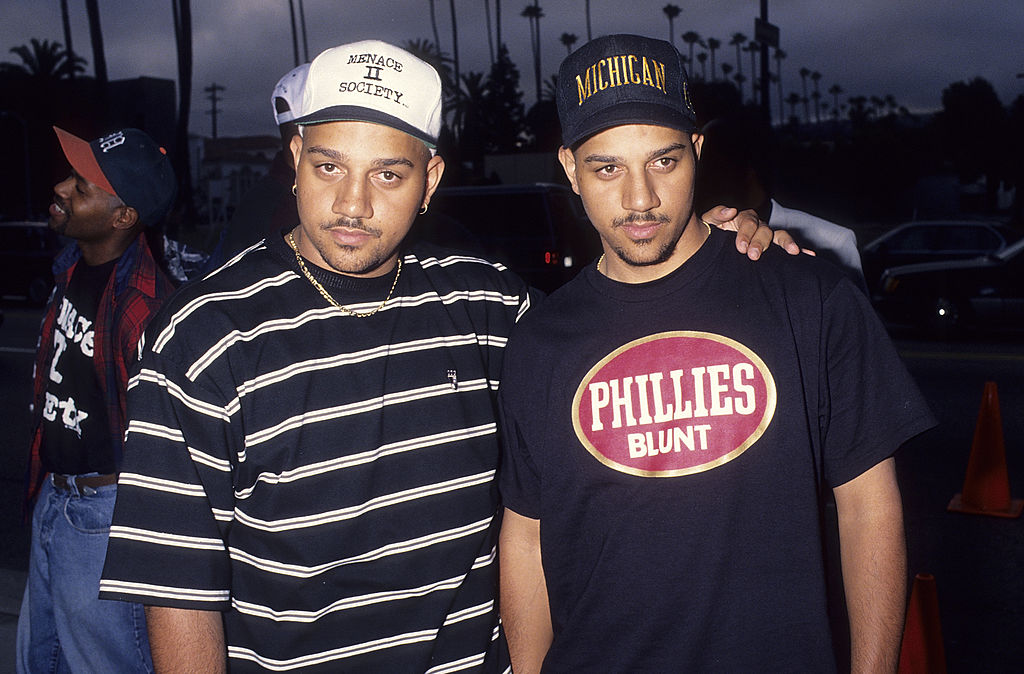

Now I call Allen Hughes, who shot with his twin brother some of Tupac’s most acclaimed music videos—including “Brenda’s Got A Baby”—before firing Tupac from Menace II Society. Hughes was then beaten by a pack of Tupac’s thugs, before this year releasing Dear Mama, a five-part documentary about the slain rapper and his late mother.

SPIN: When did Tupac first come on your radar?

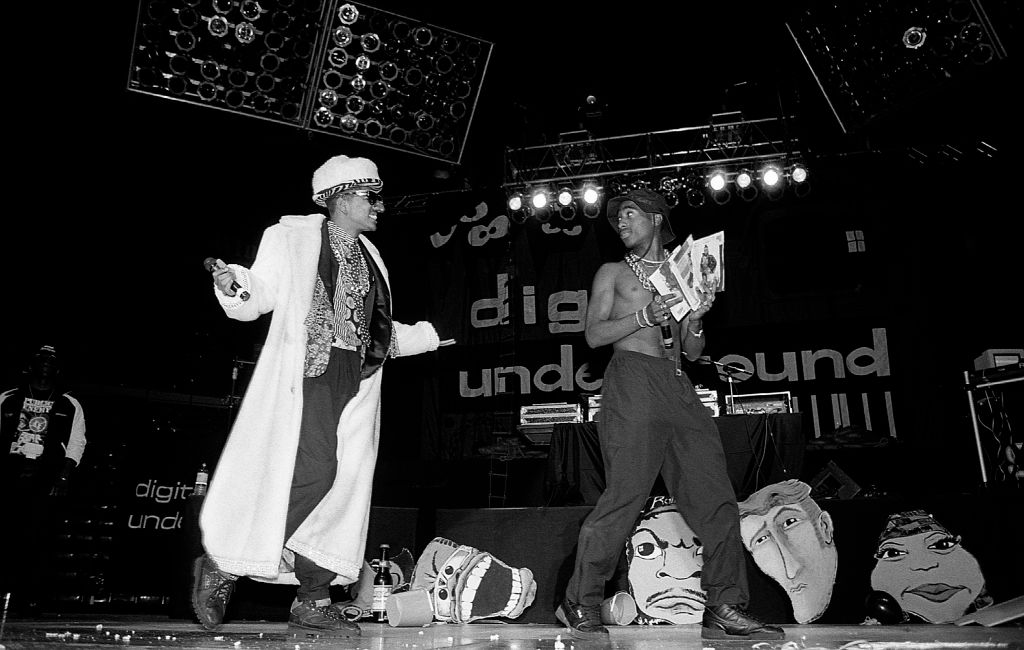

When I went up to meet Digital Underground in ‘91, ’cause we were doing our first music video for a spinoff group. We met them at a Pancake House and Tupac was at the end of the table. He was a nobody then, but I was taken with him immediately. And that’s just what it was with him. You’re like, “Who is this dude?” I was completely captivated. Everyone in that room was taken. Tupac had the floor and never ceded it to anyone.

How old were you then?

Nineteen.

What was it about Tupac?

It was everything. Sense of humor was the number one thing. He was the funniest guy in the room – roasting everyone at the table. Snapping on them, as they say – used to be called the dozens: talking about people’s mothers and this, that, and the other. It was the charisma, the laughter, the smile. But I don’t think I noticed his looks initially. That wasn’t the thing that struck me: it was the spirit. When I meet a star—and here I’m talking about a person that’s a rock star in life that no one’s ever heard of—I naturally gravitate towards charisma.

How did it go shooting his videos?

Really well. The first music video was “Trapped“. The second music video was “Brenda’s Got a Baby“, which was our crown jewel at the time: a beautiful black and white narrative. The last video was “If My Homie Calls”, and by that time our relationship was fracturing.

He had just booked the John Singleton movie, Poetic Justice (1993). He was dealing with the challenges of fame. And he was starting to show signs of being erratic. So much so that with shooting “Brenda’s got a Baby”, his manager says, “You guys only have a couple hours with him in the morning, then he has gotta fly to somewhere.”

And we were like, “Thank God.”

We shot Tupac in downtown Oakland – it was January of ‘92. We shot him out in two hours, and he left, and then we shot narrative for the rest of the day. With the relationship fracturing we were happy to shoot him out that quickly. But you wouldn’t know it. When you see the video, you’re like, “God he’s so powerful.”

So 1992 is when a six year old boy is shot dead with a bullet fired from a gun Tupac drew during a brawl. Did you get a sense his persona and behavior were changing?

Yeah. When Juice (the 1992 movie directed by Ernest R. Dickerson) came out he saw that gangster character really worked for him with the critics and the audiences. They really responded. In my opinion that was really the beginning of it for him.

Tupac signed his record deal three years too late. He signed in ’91, when hip hop is all about gangster rap, ’88 was when the music he wanted to make would’ve fit in more. That was when you had Public Enemy and you had the X Clan and very Afrocentric groups talking about social justice and activism. That was ’88. But later—even later in ’88—you had N.W.A. and Straight Outta Compton. And the rest is history: everything becomes gangster rap.

You see him—that conflict within him—on the first album (2pacalypse Now, 1991), and then especially on the second album (Strictly 4 My N.I.G.G.A.Z.., 1993). There’s these meaningful, poignant, profound tracks. And then you hear these gangster tracks. On these first two albums he was trying to reconcile that.

But ultimately he gave into the gangster image and lifestyle as a means to garner attention. He thought he needed to get the message out, but unfortunately, he got swallowed up by the image and the lifestyle.

There is remarkable footage of Tupac in Dear Afeni saying that being all gangster works for him: it pays. He says that before he acted the thug he was broke, but now he’s rich. It’s like he sees clear financial rewards for taking that persona.

It’s very complex when it comes to Tupac because he had all the intelligence, all the poetry, the lyricism. He also had the random hecticness that makes any great rebel attractive and dangerous, ’cause it was seemingly random when he would go off in those tangents and he was uncontrollable. No one can tell him anything.

He was always this live wire: this third rail. One moment he could be very compassionate, understanding, almost really sensitive. And the next moment he’d just be running into a fire. He was like that from the moment I met him.

Who knows, you know, how he came up, the trauma that he inherited, that he was born into, the expectations from the [Black] Panther party that he was born into, and all that the FBI did to his family and friends. The paranoia that comes from that: from seeing the feds dismantle your family one by one, send ’em to prison, shoot ’em dead, or run ’em outta the country.

I’m sure that’s what led to all that emotional alchemy that was Tupac, what made him so great and what made him the fallible figure he is.

It was an intense time and circumstances he was born into – the Panthers setting up in Algiers with the Algerian government recognizing the Panthers and Timothy Leary taking refuge with them there and –

That’s some deep shit, man.

So what happened with Tupac and Menace II Society?

He was meant to play the nonviolent Muslim role of Sharif but, as we started getting towards production, he started becoming very problematic. He just wasn’t agreeable, and it was hard to contain that. I tried to discuss it with him, and he wasn’t listening to reason, so we had to let him go.

Who did Tupac want to play?

Oh he had agreed to play Sharif. But when you’re looking at the timeline of things—back to the gangster thing happening in the culture—once we got around to doing it, he was uncomfortable playing the nonviolent role. He wanted us to write in how he got to be nonviolent. And by that time, the relationship was so fractured that I didn’t want to do that. He made it to two rehearsals and that’s when it imploded.

Did he have an entourage at this stage?

He had three, four guys at all times. Not when we were in rehearsals. He was there by himself, but he would get dropped off by a crew.

So what happened with the beating you got?

He showed up to a music-video set for Spice 1 for the Menace soundtrack. Tupac was already there with like 10, 12 gangsters all liquored up and weeded up.

We had a confrontation, and I could see in his eyes that every time he asked me a question, he knew what I was saying was the truth because Tupac wasn’t a liar. But he had already taken it to that point where he had all those guys.

When it was one-on-one, it didn’t look too pretty for him, so those guys he brought handled business for him.

There’s a palpable sense when there’s 12 guys on you. You’re going, “I’m probably gonna die right now.” But your adrenaline kicks in, and you don’t feel anything. Your body’s moving, but you don’t feel a thing. But I remember in the moment going, “I better be prepared to die right now.” It got pretty ugly: 10, 12 guys on me.

Then they screeched off, and I had to go to the hospital.

Was your brother (twin and co-director) Albert Hughes around?

[Hughes holds up his hand and wiggles his fingers like a person running away]. I’ll just do like that. He didn’t get caught up in the thing. He escaped.

That cause any problems between you two?

Sure, but especially recently. Back then I was really glad that Albert didn’t get mixed up in, because it would’ve been ugly for Tupac if my brother had gotten attacked. I was always the big brother in that way. So if I had seen them put their hands on my brother, it would’ve been a different story. Let’s put it that way.

What state did the beating leave you in?

I was bloody and bruised. Don’t know if I was concussed or not. I protected my neck, but the worst was a laceration that I still have on my nose.

Had you fought much as a kid?

I had fights every year. I had never been beaten up. Right. Even the fight that I lost in junior high, I never got beat up.

Ever done any boxing?

I’d done boxing as a young teenager.

Boxing works.

Oh yeah. Way better than karate or kung fu.

After the beating were you in shock? How did it fit into your life?

I don’t even remember being shook by what happened. I had no time to be traumatized by what happened. You gotta look at the timeline; we were showing up for the music video for the Menace II Society soundtrack, which went on to do platinum and do very well. We then went to the Cannes Film Festival and we’re like the toast of the town out there. Siskel and Ebert [film critics Gene Siskel and Roger Ebert] ran up on us, and their reviews were insane.

We were caught up in such a whirlwind, you know, and the New York Times, the New Yorker, Richard Avedon shooting our photo, the Today show, our Arsenio Hall show – we were everywhere, and we were shocked because we didn’t like the film, but people were reacting to the way we wanted them to react to the film we wanted to make. We were like, ‘Holy shit!’, so there was no time.

I never thought about it until doing interviews for Dear Mama. I never thought about it. I never knew there was even any trauma there – that new word that we use now: trauma. Never thought about it.

The show must go on.

It would’ve been worse if Menace was a disaster and bomb. I’m sure I would’ve thought about it, you know, but it wasn’t. And as the legendary football coach and on-air analyst John Madden always says, victory is the best deodorant.

Did you have any kind of hate afterwards or threats after the falling out?

No, because he apologized right as he was going into prison [in 1995 Shakur served eight months for sexual abuse]. He apologized to us and he apologized to Quincy Jones [Tupac had allegedly insulted Jones and his daughters because their mother, Jone’s wife, was not Black]. I would have more problems [in later years] with online fans. But back then there was no threat. I never was around that Death Row stuff that Tim [Roth] was referring to. The Death Row stuff was just so hostile. It was like the wild west at that point, you know – all that street stuff happening in Suge Knight’s wake. It was very dangerous.

An interesting character, Mr Knight.

Say the least. How you fuck all that up is beyond me. How you have tens of millions of dollars—over a $150 million company—and continue that type of activity, and people say you’re smart. I’m like, “Sure he is.” If I was making that kind of paper with those artists I would move everyone to Hawaii and just shut the fuck up.

Tim Roth was saying Tupac was still a boy and there was so much growth to go through. It brought Richard Pryor to mind: how Pryor changed, how he went through serious shifts over time.

Hell yeah. Tupac would’ve become a different artist. I think as he matured he would realize that he didn’t have to personify a gangster. He could personify what his original intent was, which is what Dear Mama‘s about. Like, what’s the purpose here? What’s the meaning of this journey? What’s the melody in this narrative?

And it was social justice warrior: art as activism. I think he would’ve came around to purely doing that. That’s what I hear from his family and friends, and from when you study his writings and his plans – ’cause he wrote on everything.

Death Row was something he was moving through – a temporary thing. An end to a means. He meant to get back to the community work he wanted to do. He wrote this out: all the meaningful songs and lyrics, and he was planning on getting back to that.

So the unfortunate thing was when he was cut down, he had plans to be more into the moving, poetic community, active-activist stuff that he always wanted to do.

He was angry when he was in prison. He didn’t sit in prison and cool off. He sat in prison and got angry. He felt that he was double crossed. He felt no one had his back. He felt that here he was making these poignant songs like “Dear Mama” and he wasn’t really being acknowledged for it. So it was “What am I doing all this for?” He talks about this in the film [the Dear Mama documentary]. They [interviewers in prison] are like, “Your album’s number one with Dear Mama.” He’s goes, “I didn’t get no awards for it, though.”

Did your thinking about him change doing the doco?

Yeah. I had never realized that I didn’t have much compassion for him before. And through the journey of making Dear Mama I came to big time compassion for him now: complete understanding and compassion.

I didn’t understand a lot before. And I’m a pretty tuned-in guy, pretty aware, pretty empathic, but there was a lot about him I didn’t understand, and I just didn’t have any compassion.

Now I have compassion off the chart for him and his journey, and especially for his mother and her journey. I feel him and I understand him, and I don’t have any question marks anymore. And I hope that anyone who did, when they walk away from Dear Mama, there’s no question marks there.

What about things like six year old kid who got shot in the head? Or the sexual abuse? Seems there is a lot of collateral damage around this kind of lifestyle. I can imagine a lot of people judging anyone involved in all that fairly permanently. Writing them off as thugs and that’s that. But is all that just part of life in a messy world?

When you’re running around hectic like he was, things are gonna happen. Especially at that time: it was a dangerous time in hip hop because the streets—the ghetto streets—were in the executive suites now. Art was imitating life, and life was imitating art, and that had never happened before.

You got gang culture in music big time now, so if you’re moving hectic the way Tupac was – things are gonna happen. And Tupac was hectic. That was his middle name. Even though in the case of this beautiful boy, Tupac didn’t pull the trigger or have anything to do with that part of it. That was the event he was involved in, though, so he had to carry that guilt and that burden the rest of his life.

America seems like a turbulent, unstable place.

The foundation of this country is crime and guns. That’s just what it is. And race and space. And we’ve never gotten away from crime and guns. This is who we are. It’s in our DNA. So it’s very American.

Handgun violence or shooting someone to take their shit is as American as apple pie. That’s the Wild West. And before that it’s the Boston Tea Party.

It’s also an articulate, verbally uninhibited place.

It’s interesting you say that because, when you think about an uninhibited, verbal, articulate place, hip hop is the complete manifestation of the wild, wild west. Hip hop is the only art form outside of stand-up comedy where you can literally say what the fuck you want to say when you want to say it, and how you want to say it.

And let’s think about stand-up comedy – one of the art forms I love the most. You mention Richard Pryor: he’s one of my great heroes. There were only a few who could do that. George Carlin, Richard Pryor, Lenny Bruce, and then it was Mark Twain.

But hip hop was the only art form where you can literally do that on steroids to a dope beat, to a Minnie Riperton sample, gospel, country and western—whatever the fuck you want—it enveloped it. Hip hop, like America, colonizes everything.

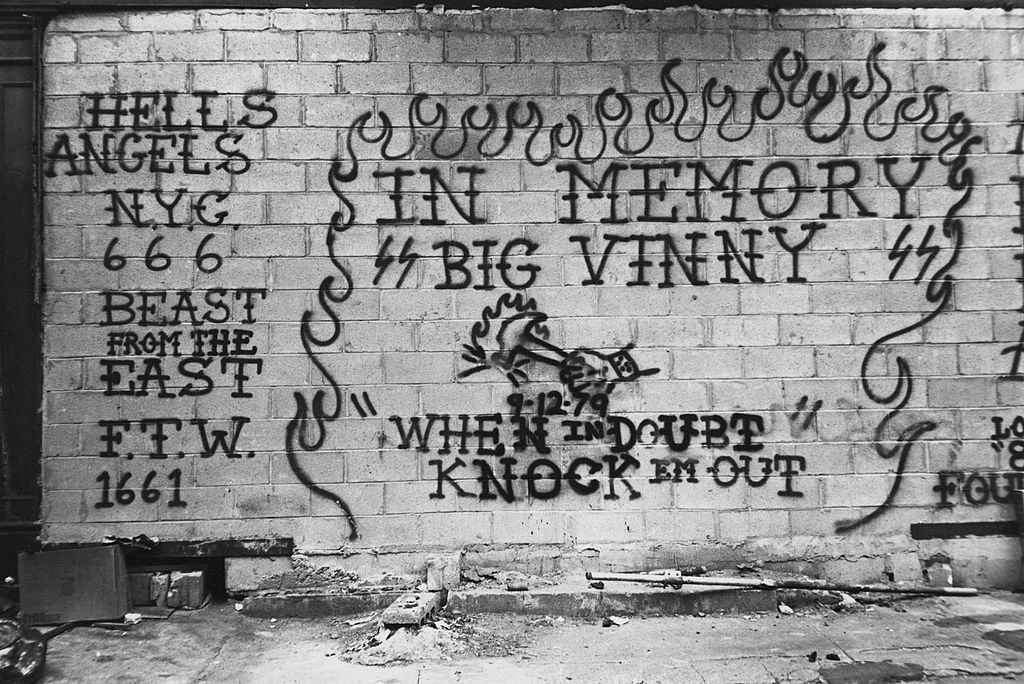

So is hip hop a philosophy and ideology? Is it more than its components? What is it?

There’s no difference between hip hop and a motorcycle club or motorcycle gang [except aesthetics]. Within the motorcycle gang, they listen to rock. They wear certain things. They roll a certain way. They got a certain lexicon – a vernacular.

But unlike the Hell’s Angels, hip hop is not limited to one thing like that. It is unique in its ability to mutate, transform, takeover, inhabit, in its insidious ways.

I don’t believe in the whole thing that the white establishment is trying to control it. I don’t. I think everyone’s always trying to monetize. Control is a whole ‘nother thing, where you’re like, “I gotta dominate these niggas.”

I don’t think that’s a conspiracy theory. I think they want to monetize it. And obviously it worked: to the point where it’s the number one genre in the world right now.

What was the last time you saw Tupac?

At the courthouse. After he wouldn’t agree to meet me, and I said, “All right, well, we’re gonna go to court,” and there was an altercation in the court hallway.

And that’s sad, because the only regret I have about that really was that I didn’t have the maturity to go see him in prison. We were making Dead Presidents in New York at the time, and I could have gone up there one weekend and saw him. And because I would have had a captive audience. I know we could have we could have connected again, and that’s my bad.

Did you think about going to visit him?

No. There was always this anger down there that I didn’t acknowledge. I wasn’t mature enough to go, “Hey, Allen, you should go see him. He’s not going anywhere. He’s in prison. And he’s gonna be open to the connection.” So it just was me. I was in a place where I hadn’t forgiven him. And I didn’t realize in time. It wasn’t till I was doing press on Dear Mama, like two months ago, that I realized I just now forgave him.

What is your next project?

A bio-pic of Snoop Dogg: his life leading up to the Chronic [Dr. Dre’s 1992 album which features the then-emerging Snoop], and then Doggystyle [Snoop’s 1993 debut album] and what happens to Death Row. That period of time. It’s like Snoop 17 to 27.

Who’s playing Snoop?

That’s the million dollar question. Who can play Snoop?

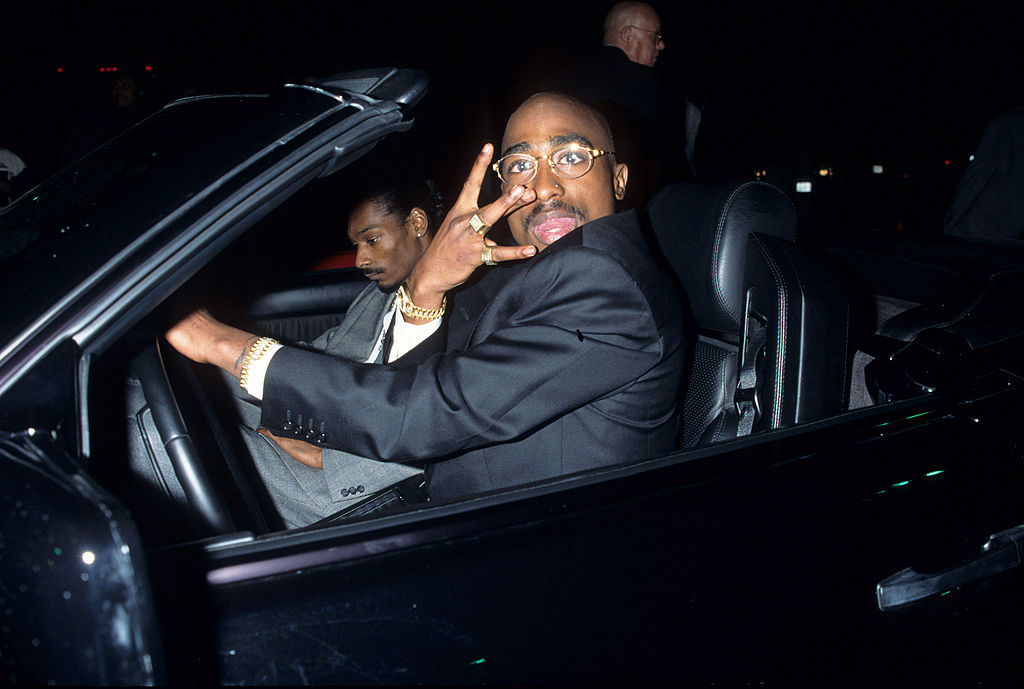

While watching Dear Mama and seeing Tupac being shiny and charismatic, I found myself really intrigued by Snoop. While Tupac is radiant and talking all the time, Snoop’s such a intriguing cat: angular, and holding things back.

Snoop is a remarkable human being. There’s that moment in Dear Mama where they’re backstage at the MTV video awards and Tupac’s doing all this [gang-style puffery]. But Snoop really did gang bang. Snoop really sold crack. Yep. Snoop really was Crippin’. Snoop really comes from Long Beach. And that’s what you see: a wise soul sitting back going, “This shit has got to stop.” You can see it on him. He knows something’s gonna happen. He has the street knowledge and acumen to know that something’s funny [as in, something’s off].

Snoop really does look like: “Would you just shut up.”

Straight up. He knew Tupac is an artist, a myth maker, a fight of fantasy. He [Tupac] is living in that. The thing that I discovered on Dear Mama was he truly is an artist. He’s a poet. He don’t see the world the way normal people see the world. He don’t see danger the way normal people see danger. I got in trouble with the [Shakur] family when I said this, but pure artists are delusional. Yeah. That’s part of what makes them great artists: they’re delusional. They’re sharing their delusions with us. But they don’t think they’re delusions : it’s real to them. So they don’t see the reality of things. They see the dream of it all. They’re living in a dream. That’s part of what made him so special.

Tupac was subjecting us to his fantasies, but they weren’t fantasies to him.

Did Snoop take him seriously?

Yeah. Snoop really respected Tupac. I think Snoop knew that that [Tupac’s public mouthing-off] was crossing the line. But Snoop respected him. At first I didn’t understand why, because when Tupac came Snoop was the rockstar. But he dimmed his [own] light for Tupac. Snoop says Tupac couldn’t bring gang-banging to hip hop, but what Tupac could bring was his military mindset and his discipline – the community-organizing mindset that he got from the Panthers. He could bring that military structure – that discipline that the Panthers had.

That’s what Tupac brought to hip hop. He was trying it to bring to the streets; he was trying to bring it to Death Row. And Snoop says, “We didn’t have that.” And he says that Tupac had a work ethic that Snoop and them had never seen.

And Snoop is a Libra and Libras are balance and options. And Snoop recognized that this dude’s a rockstar – as Snoop is. And Snoop has a gift that I’ve rarely seen in any star of his caliber: he’s a soldier-leader, so he could be a leader, but he can also be a soldier. He could be just as comfortable being a soldier as he is a leader. Snoop has that ability. So when Tupac came, Snoop wanted that [Panther-style] leadership, he played the soldier to Tupac’s leader. Which is very unique for someone in Snoop’s position.

[The discussion turns back to a striking scene in Menace II Society where gang-bangers about to do a drive-by close on their target, some bare-faced and others in ski-masks.]

That’s why Tupac was bringing discipline: like we all wear masks or we’re not wearing masks.

The title of this article, “How Dangerous A Mask Can Be”, is a quote from The Name of the Wind by Patrick Rothfuss.