Few pop songs evoke such an overwhelming, immediate rush of pure joy more than Dexys Midnight Runners’ No. 1 hit “Come On Eileen.” In the world of 1982 pop radio, there was simply nothing like it – with its Celtic melody and fiddle – its relatable musical-telling of the exhilaration of love and innocence, felt by millions across the globe and throughout the decades that followed.

But Britain’s biggest-selling single of 1982 almost didn’t happen, according to frontman, Kevin Rowland, who co-wrote the song with Jim Patterson and Billy Adams. Rowland recalls being under extreme pressure to produce a hit amidst turmoil with the band and following several disappointing singles.

“By about 1981, end of the year into ’82, a good few in the band were starting to give up on the dream,” Rowland says. “I’d said to them, ‘Look, guys, the first album did well. We’re going to write a new album that’s going to do well. It’s going to be great.’ Some of them weren’t getting paid too often. There was a bit of an atmosphere, quite a lot of an atmosphere. I was a very strict leader as well, too strict, I’m sure. I really felt under pressure. The last couple of singles hadn’t really set the world alight. We weren’t flavor of the month with the record label.”

The video served to further the song’s story and the band’s enticing lore, just when the ‘80s British invasion was introducing America to a new wave of talent. In the video, we witness Rowland wooing “Eileen” – played by Máire Fahey, sister of Bananarama’s Siobhan — and introducing us to an entire fleet of overall-clad, unmistakably English ragamuffins strumming banjos and rocking the accordion on a working-class London street corner. The heartwarming portrayal of characters seemingly from a different time served to make them – and the song – sweetly timeless.

Amongst all of its achievements, and despite its ominous beginnings, “Come on Eileen” took home the award for Best British Single at the 1983 Brit Awards.

Kevin Rowland continued making music throughout the decades, by 2012 he and a newer version of the band shortened the name to Dexys, “just to say it’s us, but we’re different now,” Rowland explains. In July, Dexys released their fifth studio album The Feminine Divine, continuing the band’s tradition of alluring, heartwarming storytelling in a full concept album. “It’s got a narrative,” Rowland says, relaying how the songs reflect one man’s internal evolution, sparked by his renewed attitude towards women.

“It’s quite personal,” he says, of his songs and his process, “and when you put it out, you feel like you are really bearing yourself.”

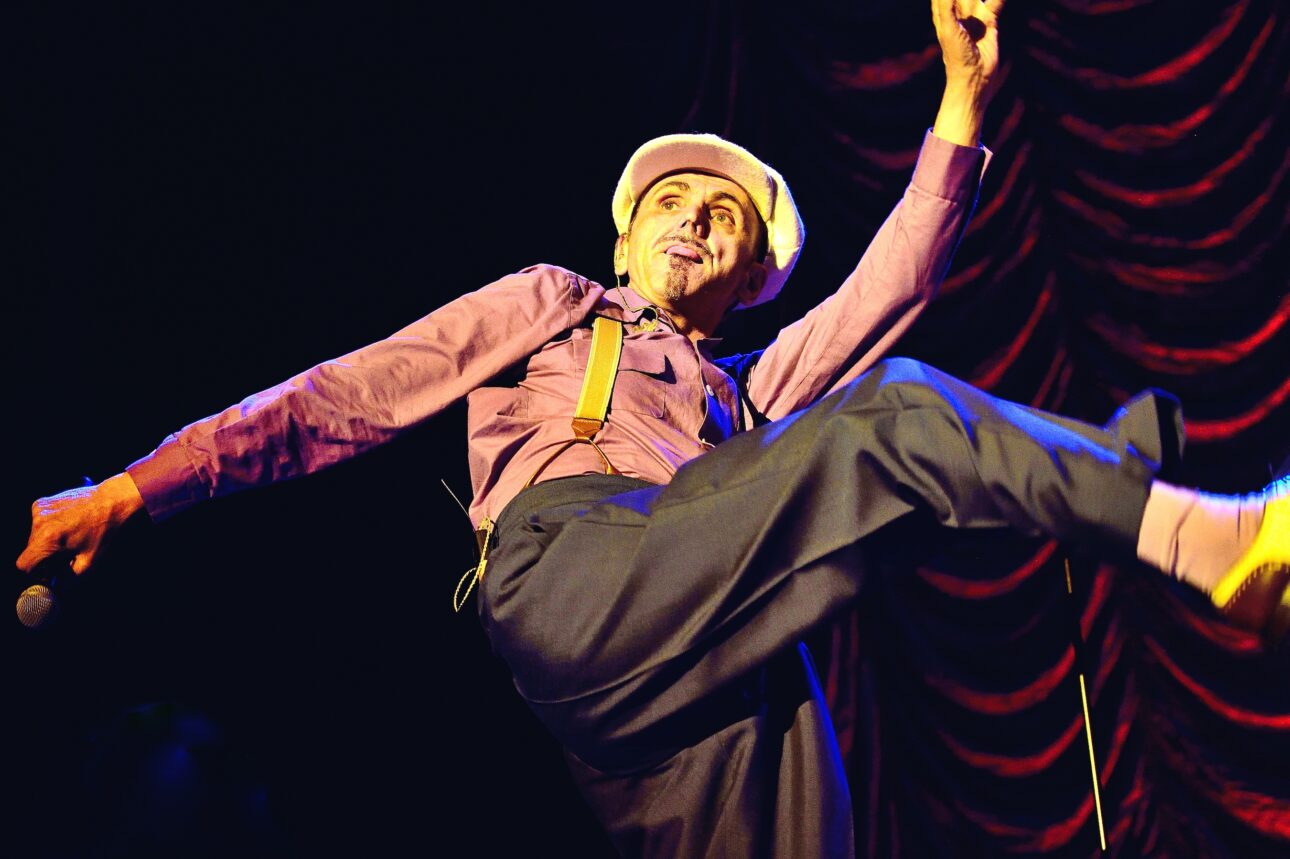

Their tour this fall will include the US – for the first time since 1983. Rowland promises a “very theatrical performance,” with the first half of the show “acting out” the new album. And yes, they’ll be playing “Come on Eileen.” All these years later, he feels the song belongs less to him and more to its audience. “I’m grateful for what I’ve been given from it, but it’s not mine anymore. It’s your experience or whoever it’s making feel good. It’s out there and it’s got a life of its own. My job as an artist is just to keep moving forward and that’s what I’m into. I’m totally into what I’m doing now, but still grateful for it.”

From his home in Northeast London, Rowland tells us the whole story behind the beloved megahit.

My songwriting partner was Big Jim Patterson. Most of that album [Too-Rye-Ay] we wrote together. This would be late 1981 into early ’82. We were under a lot of pressure. Our first band broke up in 1980. About half the band left. Then we just got some new guys in. For some reason, we had an eight-piece band, and of course, they had to be paid. It wasn’t always easy to pay everybody.

We definitely got the impression if that album didn’t do well, it would’ve been bye-bye. There was a lot of pressure internally and externally around the band. The manager was losing interest. He was having to put his own money in to pay wages, and he was getting fed up. He was clear about that.

We’d written a song, Jim and I called, “Yes Let’s,” and it had some of the lyrics that later ended up in “Eileen,” like Poor Johnny Ray sounded sad upon the radio, but a different melody, a different rhythm. We started to write this thing, Jim and I. We had a few bits for it. We had that chorus which I knew was good. We had diverse melody, but we had different chords under it. Jim was under a lot of pressure. He was getting fed up.

I just didn’t understand why anybody would want a life outside of the band. Jim wanted to go home and see his girlfriend. Invariably I’d say, “Jim, come on. Let’s go and write this evening,” after rehearsing all day.

We had a draft of the song, we had a draft of “Eileen.” I always felt nervous bringing a song to rehearsal to show the band because you never know. You feel it’s good, but you think it could be rubbish and they’re going to laugh at you, or they’re going to say, “That’s crap. I’m not playing that,” or whatever. This day was a particularly tense day, the day we brought “Eileen” in. I was showing the band, showing them the chords, and Jim was showing the brass guys what to play and stuff. I was getting everyone doing the backing vocals. We didn’t have the words for the bit that goes, Come on Eileen, ta-loo-rye-a. I was getting the guys to sing bap bap bap bap ba ra ra ra, bap bap, just to give an idea.

I could just feel the tension in the room. Whereas when they had joined a year, 18 months earlier, they’re all listening to me, “Oh, yes, Kevin, what do you want to do?” Now they weren’t listening to me. They were just pissed off, no money, working hard. I was showing Brian, one guy, the alto sax player, this bit to sing. The rest of the band, the other six were watching this. There was a bit of this play-acting going on between me and him. I was trying to encourage him to sing and I said, “No, no. It’s not so soft, it should be more of a chant, like a chant. Can you do it like a chant?” He went, “I know what it is, but I don’t like it.” I suppose I was quite crestfallen in front of all the band, they’re watching. I snapped. You know what I mean? I was under pressure and I snapped. I was, “Well, if you don’t like it, fuck off,” which was out of order of course, but that’s what I said.

Jim says to me, “You can’t talk to him like that. If he’s going, I’m going,” but Jim walked out. [laughs] He didn’t come back and neither did Brian. They came back and played on the album as session players which we’ll pay them as session players, but that’s what happened. Billy Adams, who was a guitar player in the band, he helped me finish it. We finished it off and as we were writing it, I did feel this could be a really good one.

We never tried to write for a hit, but we always tried to write as good as possible. To me, commercial just means that people like it, so we never had to make a choice. In the end, it almost wrote itself.

The fiddle player, Helen O’Hara, real name Bevington, was introduced to me by Kevin Archer who was in the first Dexys, known as Al Archer, but he’d left at the beginning of ’81 to form his own band, the Blue Ox Babes. Now I was already experimenting with strings, I was trying cello and a small string quartet and stuff like that. It was sounding okay, but it wasn’t sounding amazing. He played me his demos and I liked it better what he was doing with strings.

I said, “Who’s the violin player?” He said, “Helen Bevington.” He said, “She’d be good for you.” I said, “Where’d you get her?” He said, “Down the music college,” so we went down the music college and we got Helen in it. Also, we were definitely influenced by Kevin Archer’s sound. Not the music, not any notes, not any chord sequences, not any rhythms, not any lyrics, but the style of music. He was using a Tambourin piano. We used three violins. I thought, “Oh, it does sound a bit close to Kevin Archer’s,” but we were quite competitive at the time. We’d slightly fallen out and I was just like, “Oh well, screw him.”

He had a song called, “What Does Anybody Ever Think About” by his band, the Blue Ox Babes, and that also had a breakdown in it and a speed-up which violin does. I mean, it wasn’t a unique idea, but it was an unusual idea. So I nicked that basically. Just full disclosure, Kevin gets a decent percentage of the songwriting royalties to this day and he will continue to do so.

Julien Temple was assigned to direct [the video]. We knew Julien Temple. He filmed early Sex Pistols stuff and did The Great Rock ‘n’ Roll Swindle, which was pretty awful, I must confess. We were at Top of the Pops, the UK big pop show. He came down at lunchtime and we talked and he said, “I’ve got this idea. You’re all in a club. You’re all dressed in suits. You’re playing businessmen and the waitress is called Eileen.” I said, “I don’t really fancy that.” I just said, “I think it’d be better if we could do like this,” and explained the story, what we had in mind. I don’t know where it came from, really, but I just had that idea.

He said, “Okay. If you wanted to be literal, fair enough.” I said, “Well, literal or what, but I think that’d be better.” I explained the area we wanted, like a ton of houses that I grew up [with] really, up to the age of about 11. He said, “Okay,” and he found the location and everything, and we shot it. It was a long day. Our clothes, we put a lot of thought into that, how we looked. We blew all over that.