“Leave me not behind unburied, abandoned, and without tears of lamentation – lest you bring the wrath of the gods upon thee.” – The Odyssey,

“It’s tough to find adventure in this new lame America.” – Jerry Garcia

By the end of the tour, I consider them all my friends. The glacially spinning pranayama wizards with their flowing Gandalfian beards and art-teacher ponytails. The middle-aged schlubs with Titleist dad hats and 24-ounce Coors cans, subtly revealing their tribal affiliation via the dancing bear on their striped polos. The writhing moon goddesses in celestial white linen, beholden to neither human nor lease, vagabonds with steal-your-soul smiles, divining off-kilter rhythms from the dark star void. The itinerant vegan grilled cheese entrepreneurs scrounging enough for gas from town-to-town in hopes of a miracle, the human mandalas with velvet loin cloths and wayfarer sandals. The wheelchair-bound Vietnam vets with mangy roaming dogs, bellowing about encroaching fascism and reminding us in a hacksaw voice: “If they’re not a Dead Head don’t trust them!”

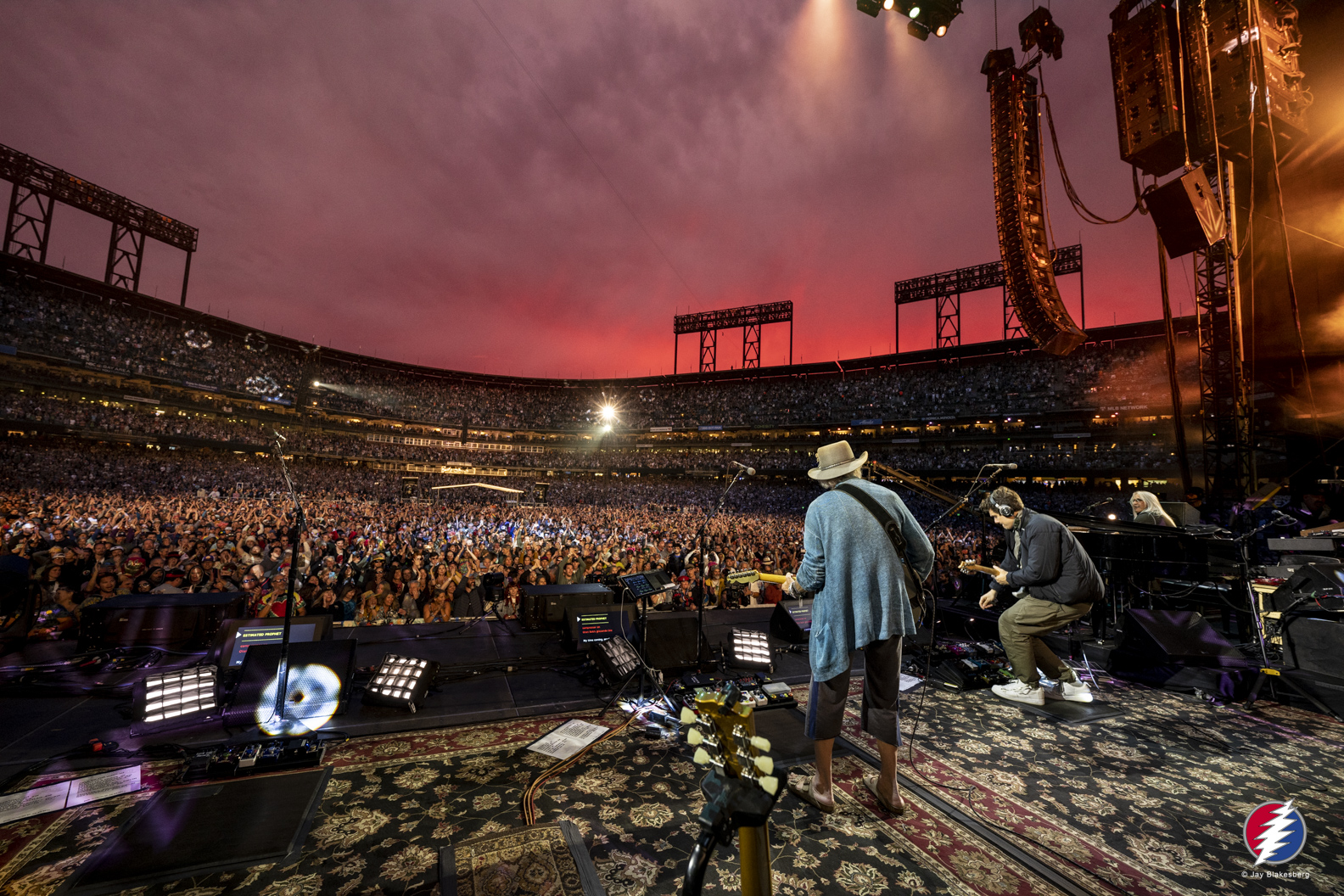

We’re gathered for a weird communion: to receive the sacraments from the wry cowboy prophet, Bob Weir, to lay roses and skulls before the shrine of St. Jerome Garcia, to fare Dead & Company well. After all, this is their “last tour,” which drew 840,000 pilgrims to 28 shows and grossed $115 million, almost the average team payroll of the baseball stadiums they’re playing in. The three hottest tickets of the summer of 2023 are Beyoncé, Taylor Swift, and the descendants of a band who achieved notoriety electrifying the acid tests alongside The Merry Pranksters, Allen Ginsberg, Hunter S. Thompson, the Hells Angels, and the hero of 1957’s On the Road (briefly Weir’s roommate).

Even though they have not ascended to the great drums/space in the sky, original bassist Phil Lesh and drummer Bill Kreutzmann are absent. But The Dead has always been more symbolic than literal. Weir ensures the unbroken chain. Drummer Mickey Hart valiantly kicks up nebulae alongside three of the most talented substitutes recruitable in Oteil Burbridge (bass), Jeff Chimenti (keyboards), and Jay Lane (drums). Of course, there is John Mayer (lead guitar and vocals) whose career metamorphosis over the last eight years has only been exceeded by the Daniels’ going from the directors of the “Turn Down for What” video to cleanly sweeping the Oscars.

More needs to be explained, but it is inexplicable to the unconverted. What I can tell you is that for a few hours, the traveling carnival promises a temporary asylum from the branded cons and schizoid alienation of modern life. These days, there are always caveats. You will have to ignore the 80-foot green steel Coca-Cola bottle at Oracle Park, the site of the final three shows, a one-time play slide until kids starting breaking their legs and parents started suing. You need to blot out the cruel erosions of time, the Soviet lines, the tickets that cost a car payment or two, the Salesforce vice presidents in greyscale Patagonia, who mistook the Dead’s quest for personal salvation and psychic freedom as justification for late Capitalist manifest destiny. You will have to reconcile the cognitive dissonance of one of Taylor Swift’s exes “crooning “Friend of the Devil” to you. Ok, that sort of makes sense.

Maybe calling us all friends isn’t entirely accurate. We are something more like co-conspirators, a mutant caste united by our allegiance to these psalms forged from woozy jug band skiffs and ragged Appalachian folk, muddy river country and moonshine string music, hellhound blues and avant-garde jazz, jukebox rock n’roll and Beat poems, after-midnight soul and Monterey purple psychedelia, sleazy insomniac disco and grandiose prog epics. A songbook ripped from the imagination of American pulp lore: tall tales of charismatic bandits and cuckolded bigamists, coked-up train conductors and Hollywood vampires, deceitful hustlers and born deadbeats.

If you are not born for this time or are seized by the notion that you took a wrong turn at some foggy crossroads but cannot retrace the trail, these songs strike a mystic chord. Ballads of death and self-destruction suffused with strength and determination. Phantom ships searching for a deeper truth, the reconciliation of contradictions, the admittance of human flaw. Something quintessentially American in their ambition, genius, indulgence, and grandeur. It’s also a fun time.

Even if Weir mystifyingly excised “One More Saturday Night” from the final setlists, the love light turned back on. Exactly 50 years ago, a landlady discovered the two-day-old corpse of their original leader, Ron “Pigpen” McKernan, in his Marin County apartment alongside a demo cassette of death letter blues. The coroner declared the 27-year-old dead from a gastrointestinal hemorrhage, and as they lay the body in the ground, Garcia proclaimed at his funeral that they all knew it was the “end of the original Grateful Dead.” In a sense, everything that follows has been a danse macabre.

Reveling in a collective afterlife is literally embedded into the band’s name. Those who have made it into the stadiums know that they are attending a Viking funeral for the deceased and living alike. Observe the nuclear families glowing from micro and macro-dosed hallucinogens. The younger generation may have been born after Jerry took his final waltz down the golden road, but they’re here to partake in a transportive spell – something to tell their disinterested future grandkids about while the sun scorches the earth. The elders need to commune with a last vestige of something they watched slowly slip away, pouring out a little for those who didn’t make it to the finish line.

I’ve lived long enough to no longer take this sort of thing for granted. When the last tour was announced, the only question was how many shows could I make it to without being forced to travel as a nitrous medicine man. I wind up at eight: two nights at the Forum in Los Angeles, three at Folsom Field in Boulder, and the final trilogy in San Francisco. My accomplices include Dead Head Hall of Fame starting center, Bill Walton, the baron of Bravo, Andy Cohn, and the white-turbaned Venice Beach eccentric Harry Perry – who followed the band from Shakedown to Shakedown all summer. It is the freaks, the heads, and the jubilant boomers bumping “Touch of Grey” from their iPhones on my Southwest flight from Burbank. It is everyone else in the fluorescent synod swaying in center, uttering familiar canticles, living for indelible moments that will soon disappear.

I’m gonna tell you how it’s gonna be

In the spring of 1957, a bespectacled 20-year old from northwest Texas found himself in a rural New Mexico town surrounded by Euclidean tracts of cotton fields and cattle ranches. What outsiders assumed was an insignificant highway offramp was really the ancestral cradle of the Clovis people (the indigenous tribe that created the first widespread culture of the Americas), and rock n’ roll itself.

Home to Norman Petty Studios, Clovis was where Buddy Holly and The Crickets decamped when his first record deal with Decca Records soured. It’s where he wrote the hits that made him one of the first teeny-bopper heartthrobs, including a B-Side that never charted called “Not Fade Away.” Less than two years later, Holly was killed along with Ritchie Valens and The Big Bopper in a plane crash on “The Day The Music Died.”

Life is short and art is long. The one-time teen Holly obsessives, Garcia and Weir quickly incorporated “Not Fade Away” into the Dead canon. They played it at the Winterland in San Francisco on the occasion of their first “retirement” in October 1974 and in all post-Dead incarnations including The Other Ones, The Dead, and Furthur. It memorably closed out the final night of the Fare Thee Well 50th anniversary celebrations in Chicago in 2015. I was there that Fourth of July at Soldier Field, while red, white, and blue fireworks exploded over Lake Michigan and tens of thousands poured out of the football stadium clapping their hands to the Bo Diddley beat, chanting over and over: “No, our love will not fade away.”

It was a moment you don’t easily forget. An acid cleanse for healthy cynicism accrued over decades uncharitable to peace and love platitudes. Jerry died before I even realized that “Scarlet Begonias” wasn’t a Sublime original. Before Fare Thee Well, I had already been to see The Dead, Ratdog, Furthur, and several cover bands. Still, nothing prepared me for the mass euphoria of 70,000 glow-in-the-dark worshippers. In this fractured and decaying era, it was evidence of something sacred and (mostly) uncorrupted. Even if I had arrived too late, it allowed me to understand the possibilities that once existed, beyond what was visible in Kodachrome documentaries.

For the next month, I worked on a 12,000 word ramble about my wanderings at Fare Thee Well, what the Dead meant to me, and how memory, love, and sound bled into something both eternal and fleeting. But as soon as I was ready to publish the story, the Dead & Company lineup was announced. Nihilism encroached. I’d already seen the survivors play with Warren Haynes, Trey, and my personal favorite, the ersatz Jerry from Dark Star Orchestra (a garland for John Kadlecik). But adding John Mayer felt shameless and ungainly. No matter how many swimming pool epiphanies he’d had to “Althea,” I could not countenance hearing spirituals hummed by a dude who had told Playboy just five years prior: “My dick is sort of like a white supremacist. I’ve got a Benetton heart and a fuckin’ David Duke cock.”

Everyone deserves an opportunity for redemption, but I wasn’t obliged to participate. So I passed on Dead & Company – no matter how many times Deadhead friends told me that “it’s actually pretty sick,” “Mayer totally shreds” and I should just get over myself. It felt like visiting a beloved relative in hospice after already saying a formal goodbye. My final memories couldn’t become a death-knell farce. How could I watch the Uncle John’s Your Body Is A Wonderland Band sing about living in a silver mine called beggar’s tomb?

Look, I had made peace with the Dead dying again in Chicago. I could wait out what figured to be a passing stunt. If a fix was required, Weir and the Wolf Bros and Phil Lesh and Friends were still on tour. Besides Dark Star Orchestra, a new generation of Dead tribute acts (Joe Russo’s Almost Dead, The Grateful Shred) started to sell out multiple-night runs at venues across America. Phish were playing at their highest level since the 2009 reunion. And King Gizzard and The Lizard Wizard were whipping up psych-rock storms hard, fast, and filthy enough to mend the frayed social fabric between heshers and wooks.

Despite my best protests, they pulled me back in like the heist cliche. It was the summer of 2019, the sixth Dead & Company tour, and a friend had an extra to their Hollywood Bowl outing. After a half-dozen songs, my skepticism began to evaporate. Weir was front and center, a human prime meridian, both timeless and untethered from today’s world, a 49er who had discovered the secrets of the cosmos inside Terrapin Station. Mayer shrewdly understood his role: offering ballast and tasteful guitar levitations, dressing understatedly, careful not to overshadow Ace, just another gifted player in a tight but loose band. There were times when it got a little awkward, where the guitar faces got a little too “Bone Rollercoaster,” where it was a little too slowcore. But they conjured an energy vortex that had largely gone missing since Garcia finally rested his bones by the waterside on that fateful August morning in 1995.

This doesn’t detract from what preceded it. Furthur delivered the best pure live interpretation of the Dead’s music that I’ve heard. Fare Thee Well was among the most unforgettable experiences that I’ve ever struggled to explain to someone who hasn’t weathered a psychedelic war for the soul or two. But Dead & Company made it a Cultural Event again – a lightning rod to catch the odd voltage from the old trip, and allow the younger generations to expand upon it before the hour grew too late.

If you acknowledged reality with clear eyes rather than as a cultist, there was something slightly depressing about “the scene” during the late aughts and the first half of the last decade. The crowd was rapidly graying or approaching their golden years. Youthful excess had long degenerated into sad overindulgence. I will spare the full account of an acid trip at a Furthur after-party circa 2011 in a grimy warehouse district on the fringes of San Francisco – which I was only at because a chef from the Grateful Dead family invited me to discuss the notion of doing a book together. One of my college friends was thinking about joining the Marines, and I figured a trip to the mountains of the moon might snap him out of his militaristic dreams. But by 4 a.m., I was seeing lizard demons with machete claws descending from dark corners. Outside, I glimpsed Ken Kesey’s son in a jester’s hat, high as a heron, babbling at the full moon atop the recreated psychedelic bus. It was fucking bleak. The book offer never came; my friend enlisted.

You can’t strictly attribute the revitalization to Dead & Company. The critical rehab actually started in the mid-aughts when indie rockers like Animal Collective, Devendra Banhart, and Bradford Cox of Deerhunter began copping to their influence. In ’07, The Fader put Jerry on the cover of their “Icons” issue, and even received a quote from Ornette Coleman about how the Dead reached “total freedom with their creativity.” The next year, Mark Richardson’s Pitchfork column thoughtfully urged a complete reconsideration. Mind you, only 15 years prior, Kurt Cobain told a reporter: “I wouldn’t wear a tie-dyed tee-shirt unless it was dyed with the urine of Phil Collins and the blood of Jerry Garcia.”

By Fare Thee Well, the transformation was unmistakable. The after-parties were mostly booked with the usual lost-in-space holdovers, but the marquee event (for me, at least) was a salute to the Dead from Alex Bleeker and The Freaks – an ad hoc outfit that included Ira Kaplan (Yo La Tengo), Lee Ranaldo (Sonic Youth), Dave Harrington (DARKSIDE) and Ryley Walker. Even tie-dye returned to vogue, thanks to Tyler, the Creator introducing it to the streetwear generation. Nor can you discount the impact of two prestige streaming-era documentaries. First came 2015’s The Other One, an encomium to Weir on Netflix; next came 2017’s Long Strange Trip, which premiered at Sundance and was executive-produced by Martin Scorsese. In a short theatrical run prior to being released on Amazon Prime, the latter racked up one of the highest per-screen grosses of any documentary from that year.

No classic rock band was better positioned. The Dead’s historically loose copyright enforcement prefigured the age of illegal downloading, but as MP3s gave way to legal streams, casual fans and future converts could now effortlessly dig into a catalog often considered impenetrable (even if American Beauty/Workingman’s Dead/5/08/77 seem obvious entries). Becoming a Deadhead requires appreciating the radically distinct eras of the band’s live recordings and the desire to get lost in the sauce. Prior to 2015, you either needed a dependable bootleg plug or to have spent a ton on Dick’s Picks compilations. Now, it was all available for a $10 subscription fee or for free on Archive.Org. A hieratic liturgy became readily translatable.

Nothing becomes a phenomenon without tapping into a latent desire in the zeitgeist. Yes, aesthetics matter. A generation capable of saying “personal brand” without getting acid reflux discovered the most striking visual iconography in music. As lines between streetwear and high fashion blurred, the Stealie became ubiquitous. Founded in 2016, the popular Dead-centric brand, Online Ceramics, wound up in the high-end hypebeast emporium, Dover Street Market. The Grailed staple, Chinatown Market, collaborated with the Dead on a capsule run that had the dancing bears on the chests of everyone from LeBron James to Drakeo the Ruler. Even Prada started selling $1200 tie-dye t-shirts. And vintage Dead shirts on IG resellers aren’t much cheaper.

But trends are ephemeral. As America descended into chaos, tribalization became a solace. Whether political atomization or stan culture, baby-talking TikTok NPC cosplayers, or shut-in Twitch gamers, American overzealousness always meets its proper obsession. In a profoundly lonely time, exacerbated by a global pandemic that furthered internet-bred isolation, the Dead offered the antidote. It was a culture rooted in communal love and constant real-life connection, complete with its own canonized martyrs. And it dovetailed with the rising interest in the therapeutic nature of psychedelics, the mainstreaming of Burner utopianism, and the continued sterilization of the old weird America. Here was a last bastion of originality, where every night was different. A Masada in a world of estimated prophets. The bus was always boarding.

Acolytes flocked. The first full tour made $29.3 million By 2021, they raked in $50.2 million, the fifth highest of any act that year. They more than doubled it on this last rotation. Of course, Mayer’s star power helped them scale from large theaters to arenas and stadiums, but it was an integral component among many.

For this generation-spanning experiment, the music is the only control. I understand that this is a predictable take from someone who once had a marvelous time watching a Pigpen-only cover band. But no other explanation exists for why there are now well-attended festivals across America entirely devoted to the Dead multi-verse. In the fall, JRAD will probably sell out L.A.’s 5,900-capacity Greek Theater. The closest (false) comparison to make is something like the Australian Pink Floyd – who shamelessly pilfer the original band’s notes and ideas down to the inflatable pig.

No analogy will make sense as long as Weir is alive and well enough to reveal his gymming routines on Instagram. He is why I found myself returning on New Year’s Eve 2020 and Halloween weekend in 2021. Over these last eight years, the blood ran cold in most of my heroes. Lawrence Ferlinghetti and Eve Babitz, Joan Didion and Tom Wolfe, Diane Di Prima and Pharoah Sanders. Prince and David Bowie. Mike Davis and Leonard Cohen. MF DOOM and Michael McClure. All gone. And as the universe corrodes into post-literate one-dimensionality, it was a dark omen that during this span, the Dead lost their poet-lyricists, Robert Hunter and John Perry Barlow.

People die every day, but they won’t mint more Bob Weirs. He is the last of the best, the headlight on that northbound train, the rebel child who became the rambling man who became the keeper of the flame. Weir helped birth the new world, watched its ruination, and spent the autumn of his life rebuilding it. Six full decades ensuring that the music never stopped. He has withstood time with grit, soul, and a Boddhisattva’s Zen.

One step done and another begun/And I wonder how many miles?

The road causes exhaustion, pain, and grievances. Some shows are highs, others less so. As the proverb goes: sometimes the light’s all shinin’ on me/other times I can barely see. It’s no easier when the ages of the band range from 45 to 79. At the Kia Forum in Los Angeles, the energy is askew. Maybe it was the bad vibes emanating from security guards who tackled the dervishes twirling in the aisles. Maybe it just came down to it being the tour kickoff. Rust needed shaking off. Intuitive connections required a tune-up. And forgive the apostasy, but I do not need a 30-minute drums/space/jam suite every single night. When it hits, it hits. When it doesn’t, it fulfills the most reductive stereotypes about jam bands – although it is a good time to return e-mails.

No show lacks brilliant moments. At every performance, there are flashes of suspended animation, what the Greeks called kairos, where the decades dissolve and the music flows in an alembic slipstream. The audience is simultaneously possessed by sepia memories of the past, humbling gratitude for the present, and acceptance of the dark infinity that awaits us all. Dayglo pallbearers dancing in the streets.

On the first night of the Forum stretch, Weir alights into “New Speedway Boogie,” written over a half-century ago about the murder at Altamont. When he declaims, “spent a little time on the mountain, spent a little time on the hill,” the desert prophet’s bearing and wooly Old Testament beard make him seem like Moses carrying stone testaments down from Sinai (if my notes and the mushroom gummies are to be believed.)

The next night brings increased amperage. Mayer’s twin solos on “Brown Eyed Woman” are the most original notes that I’ve heard from him. If there is a knock to his technique, it’s that he usually plays beautifully but within pre-existing grooves, only occasionally discovering the secret chamber. This time, he refutes gravity with a dunk contest imagination and verticality that can match his idols. If the talent was always there, he has learned that playing with plaintive feel takes precedence over sheer firepower. It ends with Weir singing “Brokedown Palace” as if it were a requiem for all the ghosts of prematurely fallen comrades and all the haunted souls of condemned bards, and all those conscientious objectors living outside the law.

* * *

There’s a reason that Bill Walton claims to never miss a show in Boulder. Every summer since 2016 – save for the pandemic years – the population of the town practically doubles due to Deadheads. All hotel rooms are booked from the university to the Denver airport. All available venues are packed with Dead-related after-shows. Across three nights over this July 4th weekend, Dead & Company cram over 150,000 people into Folsom Field. It’s bewildering but bizarrely comforting to wander down Pearl St. and be struck by the coral reef of tie-dye: old and young, wealthy tech entrepreneurs and deep-fried street urchins, all united in their ardor for a band that has defied common sense for almost six full decades.

There is something about the Dead that ignites charismatic fervor. They were and remain popular, but have always lacked mass appeal. A litmus test for what type of sinistral and wayward soul you inhabit – an instant bond between aloof strangers. But no matter the fanaticism of the adherents, there is a ceiling on converts willing to listen to 15-minute songs about the shadows of the moon. This is a religion composed of spiritual dissidents. Despite dozens of releases on Spotify, the Dead average only 2.7 million monthly listeners: less than ‘60s artifacts like The Lovin’ Spoonful and The Turtles, let alone The Doors (11.4 million) and Led Zeppelin (18.8 million). It’s partially because they lacked a Top 40 hit until 1987’s “Touch of Grey,” but also because of something Jerry once said: “Not everyone likes licorice, but the people who like licorice, really like licorice.”

If the Bay was the ancestral cradle, the energy shifted towards the mountain west. The hippies that left California headed to places like Boulder, Crested Butte, and Manitou Springs when land was cheap, the risk of wildfire low, and the drug policies lax. Over the next few decades, back to the soil, ski bum, and jam band dreams flourished in these arcadian corners. Colorado incubated The String Cheese Incident, Keller Williams, and The Yonder Mountain String Band, along with hundreds of more obscure bands that knew their way around a mandolin. As a 2019 Denver Post headline read: “Are We High, or is Colorado the #1 Market for Jam Bands?” As for Phish and The Dead, they might as well have their faces carved into the red sandstone slabs of the Flatiron Mountains overlooking the edges of Boulder.

There is no evidence that Walton actually attended any of the Boulder shows, but his spirit looms over us, a logical outcome for a 7-foot septuagenarian in flamboyant color. On the first night of Boulder, the band achieves a forcefield that I’ve only seen them summon twice before (Halloween 2021 at the Bowl, New Year’s Eve 2020 at Chase Center). “Let the Good Times Roll” cruises into “Truckin’” to start the weekend with a statement of purpose. They cover Howlin’ Wolf and Weir namechecks South Colorado and Denver on “Me and My Uncle.” It’s a holiday and the set list is filled with nothing but the bangers you’d want to hear on your final Saturday night: “Eyes of the World,” “Shakedown Street,” “Sugar Magnolia,” “Scarlet Begonias,” “Deal,” “Dear Mr. Fantasy” with a “Hey Jude” coda. On “St. Stephen” and “Terrapin Station,” they teleport to the other side.

To be there and willing to take the ride is to revert to your most atavistic self. In Boulder, I see spinning dance moves that owe no allegiance to rhythm, time signature, or self-consciousness: the funky egret, the Tasmanian shaman, the Telluride holy roller, the sorcerer’s shimmy, the Rocky Mountain dreidel. But for once, my eyes don’t roll and my caustic sensibilities malfunction. Any contempt for such silly but pure joy feels cheap and mean-spirited. You cannot conceive of a world outside of this moment, these hymns being played, and these people surrounding you – who you probably have very little in common with outside of a reverence for the Grateful Dead, but somehow, that is enough.

Among the circuit of fellow travelers that I run in, everyone says the Wrigley shows were remarkable. The one-off Barton Hall show in May has already become fabled. But the Boulder trilogy is the most consistently formidable that I’ve ever seen them. The final evening is interrupted by a freak rain and lightning storm, which feels like a round of applause from providential sources – especially because it comes shortly after “Cold Rain and Snow.”

The real applause comes at the end of the night when Dave Matthews joins the band to sing covers of Bob Dylan and The Band. The crowd detonates. Maybe it’s a matter of taste, but watching Matthews and John Mayer duet on “Knockin’ On Heaven’s Door” leaves me feeling like I have been suddenly transported to a Jewish summer camp that I purposely never attended. Someone around me suggests that maybe after Bobby dies, Dave and John can tour as Dead and Company, and it feels like the long black cloud is coming down.

Where have all the people gone today?

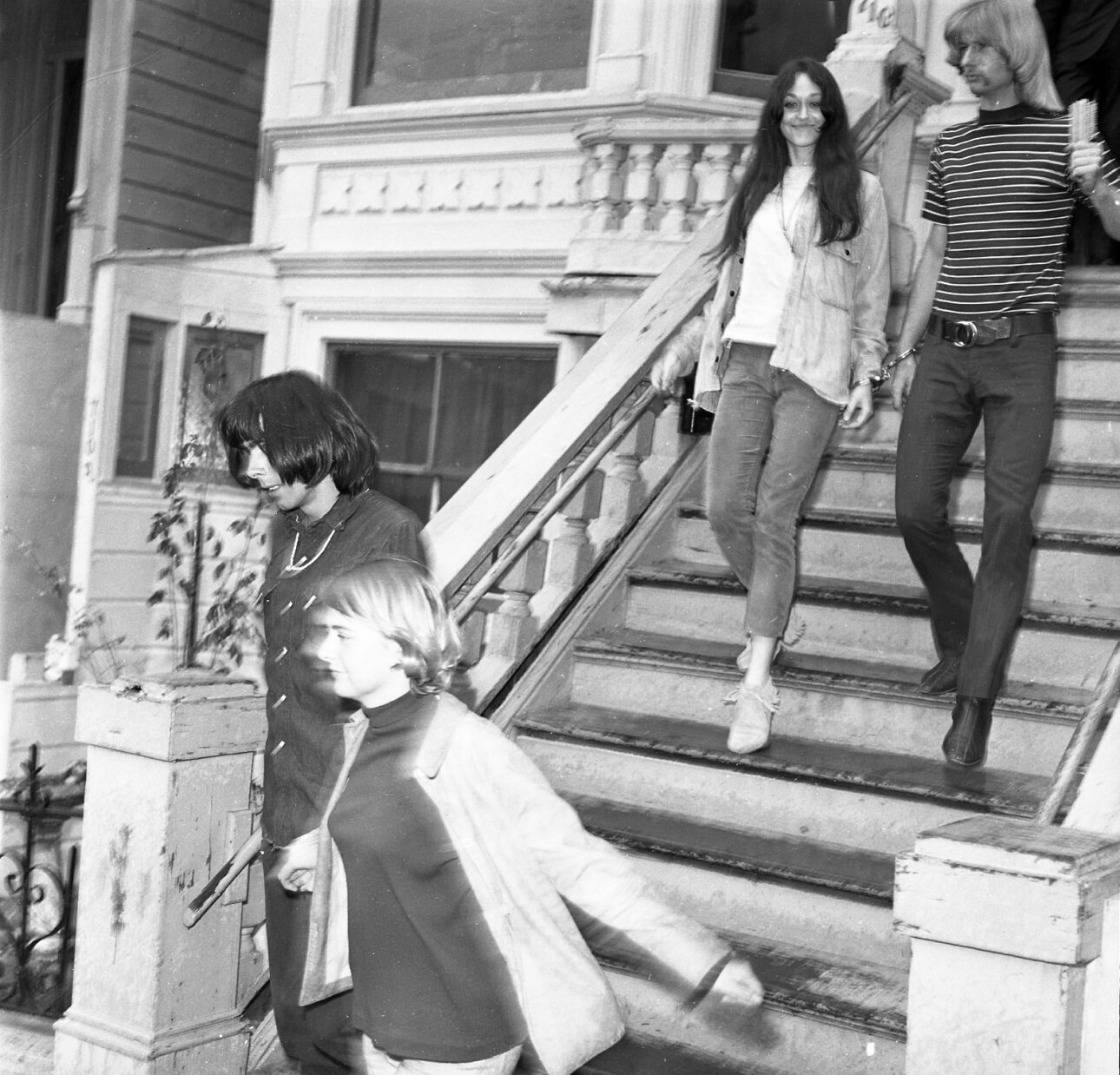

There is an Aston Martin parked in the open garage of the house next to 710 Ashbury St. Two khaki-panted, sunglassed programmers in their mid-30s lazily tinker on the $200,000 sports car. Alternately, they gawk at the tie-dye Haji posing for Instagram photos outside of the freshly painted two-story Victorian. No plaques commemorate the time that the Dead spent here from 1966 to 1968, but during the final weekend of the final tour, it might as well be the Grotto of the Apparitions.

In the fall of ‘67, the San Francisco police famously smashed in this door in search of drugs. Without a warrant, they arrested Pigpen and Weir, two managers, and seven others including Phil Lesh’s girlfriend. Outside, a Greek chorus of hippies jeered. In the kitchen, state narcotics agent Jerry Van Ramm (actually his real name) taunted the band: “That’s what ya get for dealing the killer weed!”

Head a mile in any direction from this part of the Haight and you can traipse past the one-time homes of Janis Joplin, Sid Vicious, Jack London, Graham Nash, and R. Crumb. There’s a large red apartment nearby with a Jimi Hendrix mural that the San Francisco Tourist Association once claimed as his former residence, but it turned out to be false intelligence. It’s fitting for a part of the city that’s become an Age of Aquarius Theme Park – pocked with the landmarks of past glory, but financially inhospitable to modern creative existence. The confiscated terrain of tech bros and bio-hacking “founders” inspired by Steve Jobs’ acid revelations. Zillow estimates that the Dead house would cost a cool $2.5 million on the open market. But the historical cache would mean it would be snatched up for twice that by like the 17th employee at Google, who is probably really into Burning Man and collecting autographed guitars.

The parishioners come in all ages and accents. Jerry photos on their torsos and Cats Under the Stars leg tattoos and freshly purchased San Francisco Giants-themed Dead and Company shirts. The young girls are dressed like Janis Joplin with berets and floral dresses, Woodstock vests and long ropes of beads around their necks. Aided by her granddaughter, a beatific older woman with white hair and a bright purple titanium cane struggles up the hill. She basks in the sunflower dust of memory.

A middle-aged couple in Gap jeans and reflector shades cheese with a “we’re going to Deadsneyland” smile. You either die a hero or live long enough to watch your old address become a tourist trap.

A very blonde, very sunburned Southern mom with a Cracker Barrel twang and an “I’m not like all the other girls” shirt politely approaches the tech overlords next door:

“Is it always like this?”

“You mean, are we always changing our oil?” They snicker and she appears wounded, and they try to backtrack and tell her that this is actually a particularly crowded weekend.

I stand there for a while trying to picture what it must have been like 57 years ago, but I know that I have no idea. Even if you’re able to process the whiplash epiphanies in real time, there’s no way to hold onto them. It’s only later with the fuzzy contortions and cracked glaze of memory that it starts to make sense, and by then it’s too late. What’s clear is that they saw and heard and incited things with a slippery magic that will never be replicated. They were among the last oracles. Now, this is the name of the software multi-national that paid $200 million to rechristen the ballpark where I will witness the Dead’s final form.

Shortly after Garcia decamped from the Haight to the forests across the Golden Gate Bridge, he described the band as a pointer sign whose arrows gestured towards the expansive universe and potential experiences available. But he added, “We’re also pointing to danger, to bummers. We’re pointing to whatever there is, when we’re on, when it’s really happening.”

On that first night in San Francisco, the quote echoes. I can’t help but feel like the cataracts are approaching. Maybe it’s the abrupt contrast to the alpine cheer of Boulder. This is no longer the city immortalized by the quote hanging in the old Beat bar Vesuvio: “San Francisco is 49 miles surrounded by reality.” It is now a place of brutal and rigged Darwinian reality. A black-throated wind blows off McCovey Cove in the middle of July. The congregants favor achromatic colors. The twirling here only gets half a bar.

During the first 10 minutes, teams of emergency medical technicians attend to crises on both sides of me. To my left, a gray-haired woman in her early ‘70s wilts, balled and grimacing in her Burgundy puffer coat. To my right, a balding man cog with blue Vans and Ecto-Coolor shades drops to one knee, then slowly collapses to the ground. The band opens with “Not Fade Away.” No one around me seems to be noticing the triage, certainly not when “Shakedown Street” comes on.

Unable to snap her to sentience, the medics carry the woman off on a gurney. The Yelp executive limps off on his own, lurching into the bowels of Oracle Park in search of water. Seagulls soar above. It’s one of those bitter San Francisco nights on the waterfront where it feels like the wind is poisoning your blood. Tonight’s “Cold Rain and Snow” sounds a little too slick, a little too smooth, a little too expensive.

This is not to say that the band is even remotely bad. But tonight they are a step slower, the arrangements a touch frail and perfunctory. Maybe it is the aseptic chokehold of the big tech goons. The field is dotted with wealthy middle-aged Jasons who got rich off dumb luck and avarice and proceeded to make American cities unlivable for anyone and everything worth preserving.

These are not the hippies, but the party-crashing Alex P. Keatons that came in at the end and then went off to make millions and tuned back in once they became a Thing again. It’s so crowded that I can barely lift my elbows. And I keep looking at the break-a-leg Coca-Cola slide in left and the banner reminding me to buy Levi’s and fly Alaska. This is tolerable for everyday life, but I am here to avoid this grim hustle. The set list is impeccable and the songs meticulously played. I would rather be at the most mundane Dead & Company show than almost anywhere else, but tonight, there is the sense that the signposts are tilting in the wrong direction. A bummer. It’s starting to feel like it’s time.

But the fate of the votary is to require and receive a constant renewal of faith. On the second night in San Francisco, Dead & Co’s telekinetic powers are back. Weir has returned in his felt Stetson and a long blue work shirt that looks like a robe. His eyes are wise and ancient, like cryptic glyphs carved into a rock of cold mountain. Last night’s jitteriness has faded. It partially helps that I decided to take half a tab of acid smuggled back from Barcelona – bestowed upon me there at 1:30 a.m. one night by a new friend from the Bay.

San Francisco is no longer an effective place for hallucinogens. Half a tab is plenty. Anything more and the vibrations will start to pick up on something sinister. There is a sense of suffering, the escapable inferno of the streets and sympathy for those stalwarts trying to save their native land from the crush of greed and moral bankruptcy. Earlier that afternoon, I watched an unhoused man overdose on Market Street. As he lay motionless on the pavement, several other dispossessed men circled his stricken body and screamed: “He’s gotta get Narcan’d! he’s gotta get Narcan’d!”

For a penultimate performance, night two is oddly devoid of the anthems you’d hope to hear once more. There are stretches where the cosmic explorations wander into a meteor field (though they find their way out). But there is such palpable exuberance during “Playing in the Band” that it restores your belief in the boundless capacity of this music for reinvention. Chimenti never fails to discover new pockets in these familiar wrinkles, carefully listening to Mayer’s liquid crystal leads and conjuring his own form of iridian jazz-funk. On the big screen, neon blue lasers fill in the rest of your imagination.

After a 45-minute second set detour of “The Other One” into “Terrapin Station” into “Drums/Space,” they unlock “Uncle John’s Band” with a flourish that recalls a psychedelic and orchestral Django Reinhardt. When they sweep into the hook, the 42,300 in mass recite the words like these were the first syllables memorized out of the womb. This is an epistemology that rewards your belief in the irrational, where what makes sense on the page has little bearing on what transmits from the speakers, where absolution is available to all – provided you can handle the superficially absurd.

There is no whimsy in “Morning Dew.” The Dead performed it for the first time only a handful of miles from here, at the Human Be-In at Golden Gate Park. Jan. 14, 1967. The Gathering of the Tribes had been summoned in the wake of LSD being outlawed in California. It’s where Timothy Leary appeared on the West Coast for the first time and told the masses to “turn on, tune in, and drop out.” And Allen Ginsberg chanted om’s and turned to Lawrence Ferlinghetti at a neurotic moment and whispered, “What if we’re wrong?” Owsley brought free white lightning acid for 20,000 and the Dead opened up with “Morning Dew,” a folk song first covered by Fred Neil around the time of the Cuban Missile Crisis, which Garcia had recently discovered and would include on their debut album later that year.

“Morning Dew” is a dystopian love ballad about a couple wandering amidst the ashes of nuclear apocalypse. The vaporous mist of the morning dew is really the phosphorescence of toxic radiation. A misheard baby’s cry is the scream of someone slowly dying. It is a gorgeous baleful a.m. lament about an extinction-level event, where you find yourself improbably amongst the survivors. It was sung by Garcia until Weir assumed the mantle after his passing. If you listen to the early recordings of Weir, he brays with a galloping ranch-hand charm. But it’s herky-jerky, as if a horse is trying to buck him mid-stanza.

As the years have elapsed, Weir settled into a soothing worn-leather baritone. If he used to rush the lyrics out, he now cradles them with amniotic gentleness. He’s still capable of doing rotgut blues and rollicking badlands getaways, but it’s the slower numbers that take on an otherworldly quality. Something like Johnny Cash towards the end of his run or even Dylan – an immortal dispatch from a familiar but unreachable dimension.

Here he is now, bathed in emerald-green smoke, singing a song that he first played when he was barely 19. The kid whose rhythm guitar was once buried in the mix, whose now Vedic presence and endurance mean more than anyone ever hopes to translate into hyperbolic praise. The specters of those that deboarded early are buried in the fog, the band is taking it higher and further than anyone could have ever dreamed, and I can’t help but think about what it will be like when Weir is no longer around to lead these seances. But that is a prosaic reality too painful to process. Right now, it is better to accept the supernatural parts of this transference. For a minute here, you can see everything, all the way down the line.

You’re Going to Know Just How I Feel

No one actually believes that this is the end. The band has been playing too well and the fan devotion is too strong and the money is too abundant. After all, the members of the group and their management have slyly stressed that this is merely “the last tour.” It’s a matter of course that Dead & Company will host Playing in the Sand, their four-day festival on the Mexican Riviera. But unless you are a wealthy Boomer, accepting money from a wealthy Boomer, or are adept at selling plasma, few under 50 have that level of disposable income.

The best guess is that they’ll do a few multi-night stretches a year until it becomes untenable. Maybe a Halloween fun run. A New Year’s swing. The Fourth of July in Boulder or Chicago. At least that’s the hope buoying the crowd at Oracle on the final Sunday night. If the atmosphere was excited but uptight over the first two evenings, this is somewhere between pagan solstice and jazz funeral. The rumor is that Bob Dylan might join them tonight. Or at least Kreutzmann. Or maybe a Jerry hologram (sponsored by Open AI).

It’s clear from the first notes that there is no time to waste. They’re playing at a pace that suggests that something was held in reserve. “Bertha” burns into “Good Lovin’.” Mayer and Weir have largely split lead vocals this summer, but Weir is steering the locomotive tonight. He growls “Loser” with the pained delusions of a dead-broke gambling addict. I can pay you back with one good hand. Mayer riffs like he made a deal with the devil that involved a $100,000 Rolex. Chimenti channels the spirit of Jelly Roll Morton. As soon as it ends, Burbridge croons “High Time” with an ecumenical grace that adds a gospel dimension. A white hand is painted on his face with a missing finger to honor Jerry.

Everything feels intentional. The biblical motif continues with “Samson and Delilah,” a song taught to Weir by the blind South Carolina blues legend, the Reverend Gary Davis (born 1896), during the last months of his life in 1972. The link to the origins of American folk music made explicit. Next, it’s Mayer’s moment, the weekend’s rendition of “Althea.” It has become the band’s never-fail knockout punch, his consistently most inspired and impassioned performance, the perfect blend of his skill set and the post-disco leisure-suited Dead. No less than four people send me a viral tweet posting a clip of the performance with the caption: “What John Mayer did on Althea last night was absolutely ridiculous.” Even the most inveterate hater cannot argue. This is the type of guitar solo that expunges all transgressions from the permanent record.

It’s axiomatic that the Dead is an acquired taste. If you ever question the extent of your dedication, 1975’s Blues for Allah, is the litmus test. These are sprawling multi-part prog-jam-jazz-world music suites full of obtuse lyrics about flaming angels and hopes of paradise. There are post-Watergate parables about America losing its way vis a vis the Liberty Bell metaphor of “Franklin’s Tower.” For the first thirty minutes of the second set, Dead & Company inhabit this orbit. It’s artfully executed, virtuosic, and funky. But you really have to love licorice. I finally spot Bill Walton for the first time all tour. A row of people bow in his honor.

We hear a searing “Estimated Prophet” and the dopamine valentine, “Eyes of the World.” It ends with “Sugar Magnolia,” arguably Weir’s most beloved song – a reverie that captures the sweet dazed headrush of falling in love, real love, for the first time in the April of your life. Even if the sunshine daydream affair didn’t last, 53 years later, everyone fills in their own blanks. The first time they heard it. The first time it really made sense. Where are they now?

We are sentimental and slightly melancholy and to use the parlance of the times, “in our feelings.” From the grandmother with the purple titanium cane to the shirtless dreadlocked spinners, the tie-dye families agnostically praying and even the Patagonia Mafia, whose spiritual deep freeze is thawing. A young couple hug each other tightly; his shirt reads “Don’t Be Sad, It’s Over. Be Grateful, You Were There.”

What else can they play but “Truckin?” The first song of the encore, the “On the Road” of neon-roadhouse, lost highway, psychedelic country blues. Behind them, a yellow and black animated highway appears on the screens. The band’s faces are framed in large rearview mirrors. When it comes time for “Busted down on Bourbon Street,” they flash to Jerry’s shit-eating mug shot grin, captured after the New Orleans vice squad found drugs in their French Quarter hotel room in January 1970. Is there a more evocative but open-ended lyric than “What a long strange trip it’s been?” And since then, a series of wild left turns, blind leaps, and unforeseen tragedies have led to this final destination. It is hard to imagine it ending any other way, but even more difficult to believe that it is still going, let alone at this velocity.

For the last hour, as each song fades out, the suffocating sensation of the clock running out prevails. The certitude about their return only goes so far. To listen to these songs is to wrestle with extramusical loss. When I first became a fan in my early 20s, I instinctively gravitated toward the up-tempo numbers, the mythic figures from a vanished world, the adventures awaiting me on the infinite and unbroken asphalt. But there comes a time in everyone’s life – if you’re lucky – where the cul-de-sac comes into view. You cannot help but notice that those teenage dreams may not come true, your expectations are reduced, and friends that you figured would be alongside you every step of the way are now ashes scattered in the Pacific – or immured in a marble tomb at a gravesite that you keep telling yourself to visit.

When they harmonize into the elegiac, “Brokedown Palace,” the raw emotion on the field becomes overwhelming. Tens of thousands crying or noticing the lump in their throats. The provisional bliss juxtaposed with grievous finality. Robert Hunter’s words as clear as hazard lights. A farewell to your only true love, whatever and whoever that may be. One final trip down to the river to rest your weary bones. Echoes of lost lullabies still faintly ringing. A weeping willow planted by the banks to continue the cycle after we are long gone. This is goodbye, for now. Fare Thee Well, fare thee well.

But it is too heavy for the end. The familiar 3-2 beat kicks once in more. The crowd reflexively whoops, waiting to join, but the band keeps them at bay, teasing what’s coming with an extended organ funk riff. Buddy Holly’s puppy love malt shop rock n’ roll repurposed for this numinous oath. “Not Fade Away” once again. The audience shouts every word of this reprise: I’m gonna tell you how it’s gonna be/You’re gonna give your love to me/I want to love you night and day/No our love will not fade away.”

Weir and the crowd move in synchronicity, repeating “No our love will not fade away” as a pledge and mantra. The lightning bolt flashes on stage, a floodlight prowls, the rainbow array of stage lights pulse. Over 30 times, Weir and Mayer and the crowd utter this phrase in call and response, until all the instruments cease and it is merely the words and the claps and invocations of 40,000. Then it is only the roar of the devoted. The band comes to the forefront of the stage, linking arms, and bow. All around me, people wipe away tears and yell “Thank you so much!!!” Mickey Hart takes the mic for a final gesture of gratitude: “Without you, there would be no us.”

In the sky above San Francisco Bay, a thousand drones form in electric formation. It’s the Uncle Sam Skeleton, complete with red, white, and blue top hat, which doffs to the dazzled crowd. Then slowly, it puts it back on its illuminated head and disappears, to be replaced by the dancing bear, turning burgundy and yellow and green and purple until it morphs into a glowing red rose in full bloom.

Finally, the Stealie Skull appears high in the firmament, psychedelic color swirling on its crown, while the crowd keeps whooping and clapping in time. But then that too fades into the darkness, leaving everyone satisfied but adrift. Some have already gone, but most remain, staring into the blank sky, wondering where they’re going next, waiting to see if the lights will turn back on again.