This article originally appeared in the January 1997 issue of SPIN.

The Fugees‘ Wyclef Jean leaped from the grandstand stage and climbed a chain-link fence, reassuring a panicky military policeman, “It’s cool, it’s cool, I do this every day, I’m from Brooklyn.” Then he vanished into a crowd of 15,000 delirious Trinidadians. Lauryn Hill scolded local cops holding Rottweilers at the leash (“Yo, that’s some civil-rights-movement-flashback-type shit!”), and hitched a ride on a fan’s shoulders. Prakazrel “Pras” Michel, the group’s third member, turned over the turntables to a teenage-ish local DJ, who thumped soca jams while Jean’s disembodied voice thundered under the muggy sky. “Free the dogs! Go massive!”

And we’d only reached intermission. The Fugees were playing their first-ever West Indian gig, in Port of Spain’s Queen’s Park Savannah, and Haitian-Americans Jean and Michel were hyped. Jean, who takes “MC” to literally mean “Master of Ceremonies,” later organized an “Apollo Theatre Dance Contest,” Trinidad jump-and-wine style (even butt-vets 2 Live Crew would’ve blushed). And when a couple of boastful boys bum-rushed the stage, he welcomed them slyly: “You know, if you guys ain’t the bomb, they going to stone you.”

Then… well, I’m not sure exactly what happened next, since I was prone behind the sound man, but I’d guess friendly fire consisting of every water, rum, and soda bottle within 50 yards. Calmly strolling back onto a stage now speckled with shards of tinted glass, Jean announced, grinning, “All right, all right, that’s enough.” Police stood dumbfounded, walkie-talkies buzzing lamely.

All this after an hour-and-15-minute set of no-frills hip-hop that translated fluently to the West Indian throng (dancehall superstar and opening act Super Cat, asked if he’d join the Fugees onstage, replied, “This is too good, mon, I can’t afford to fuck it up”) and the “Refugee Spelling Bee,” co-hosted by Lauryn’s mom, Val (a junior-high teacher back in Newark), won by an adorable eight-year-old who liltingly, and quite appropriately, spelled “chaos.”

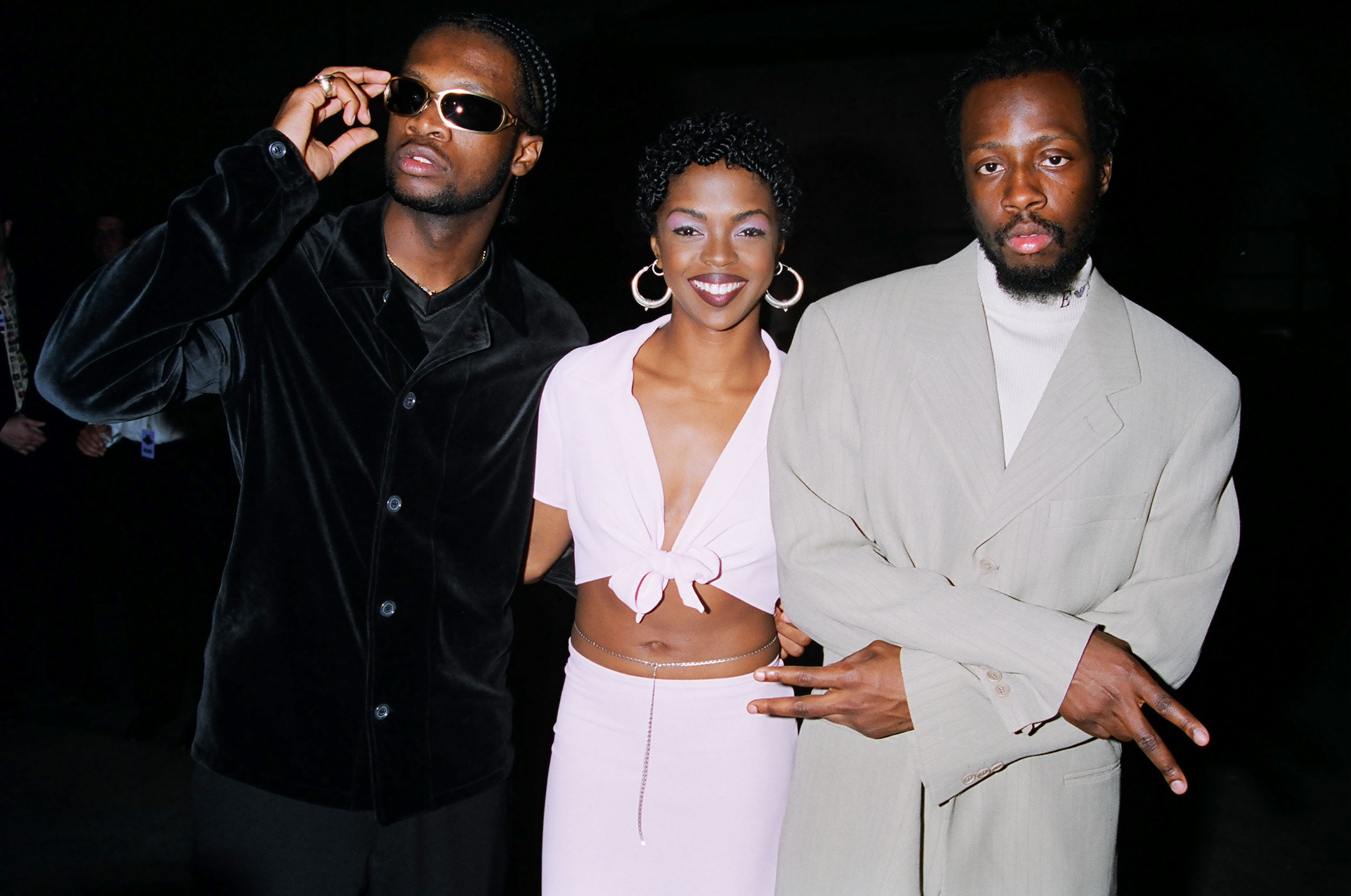

“Could you believe that shit?” says a smiling Jean afterwards, exhaustedly flopping into a folding chair in a corner of the group’s bustling tent. Hill, relaxed in an orange Armani T-shirt, denim skirt, and Timberlands, sips fruit punch nearby with her mom and her assistant Miriam, while Michel, wraparound shades propped on his elaborate cornrows, attends to the spelling-bee prize money ($300 U.S., $1.500 local currency). Between munches of callaloo stew, Jean reviews the show: “Nothing fake, nothing violent, even those cats that got stoned with the bottles were into it.” Dressed in red overalls, black briefs (which he flashed during the dance contest) and red creepers, he has the wry wink of a cocksman, but like all the Fugees, he’s got a more ambitious agenda: the humanizing of hip-hop.

“All I can say is that when I meet black kids or Chinese kids or white kids, I try to show them the universal. Any kid can be intelligent if he’s given some awareness of the world. See, I could talk about guns all day, but what am I teaching anybody? At the end of the day, nobody gives a fuck. But I feel like what were doing will help a lot of kids. Like tonight, stopping and doing a spelling bee. And. yo, the crowd was into the spelling bee. How dope is that?”

In a 1994 review of Roberta Flack’s new album (the Fugees’ breakthrough single “Killing Me Softly With His Song” was a cover of Flack’s 1973 No. 1 hit), critic Nelson George lamented that hip-hop of the past decade had been mired in “emotional reductionism—anger over romance, materialism over brotherhood, hard over soft.” With their second album, The Score, which has now sold more than five million copies in the U.S., the Fugees reversed that cycle. Unlike so many rappers who came of age in gangsta rap’s shadow, the New Jersey-based trio brashly asserted that hip-hop was pop music with the power to open up and change the world. Marshaling R&B’s intimate, vocal yearn and reggae’s boundless, spiritual pulse, the Fugees liberated hip-hop from its scowling project exile.

“I think the Fugees’ impact on hip-hop is unprecedented.” says Sylvia Rhone, chairman/CEO of Elektra Entertainment. “They’ve reawakened excitement in the genre and expanded the perception of what hip-hop is, especially to mainstream America. They dispelled all the notions about it being a violent, misogynist influence on culture.”

Without a doubt, 1996 was Endless Fugee Summer. “Killing Me Softly,” an instant classic, pumped out of every passing car from coast to coast, with Lauryn Hill’s timeless voice never losing its poignant kick. “The 21-year-old, short, dark-skinned black child,” as she describes herself, immediately went from obscurity to object of desire. The low-rent video clip, which could’ve been shot by so-and-so’s flaky third cousin Eugene, ran constantly on MTV, even winning Best R&B Video. Better still was “Ready or Not,” an eerily ambient flow of confused musings (Jean), confident harmonies (Hill), and immigrant pride (Michel), tapped insistently into your consciousness by a simple snare beat.

The group backed up the singles with a fully conceived album and kinetic live show, featuring a full band: Jean on guitar, Michel on keyboards, bassist Jerry Duplessis, drummer Donald Guillaume, and DJ Leon Higgins. Proving the Fugees’ commercial cachet, Hill’s songbird-swooping cameo on Nas’s hit single “If I Ruled the World” helped keep his album at No. 1 for four weeks. And A Tribe Called Quest, the Fugees’ most obvious progenitors, unexpectedly saw their album also enter the pop charts at No. 1. Hill, in addition to putting on this past summer’s Hoodshock concert series as part of the Refugee Camp Project (a not-for-profit youth organization), will probably record a 1997 solo album on the Fugees’ Refugee Camp label. Jean has released an EP of Creole folk songs in Haiti. And the group is expected to star in the The Harder They Fall, a sequel to the 1973 reggae-breaking film The Harder They Come starting Jimmy Cliff.

While there’s been much rightful moaning in recent years about the segregated nature of commercial radio, the Fugees actually embody a potentially genre-bending format. “They’re totally credible, musically, with our listeners, and they elicit a lot of emotion,” says Lisa Worden, music director for modern-rock radio giant KROQ in Los Angeles. “The Fugees are the only hip-hop group that it makes absolute sense to play on an alternative station.”

But most of all, the Fugees refocused attention on hip-hop’s artistic essence—the eager mixing of any available culture into an original voice that speaks to our mixed-up times. They convinced non- and former believers that the genre wasn’t creatively obsolete. Or as Busta Rhymes, a fellow artist on this past summer’s Smokin’ Grooves tour, summed it up succinctly, “The Fugees showed that hip-hop can be successful without killing one million motherfuckers. They showed you can be hardcore without killing one million motherfuckers.”

Even as a three-year-old, Lauryn Hill was always onstage. Enamored with Michael Jackson, she’d bust out “ABC” dance routines during Thanksgiving dinner at her parents’ house in the Newark suburb of South Orange, New Jersey. At four or five, she caught the Annie bug, warbling “Tomorrow” day and night. She even did a take-off on Brooke Shields’s Calvin Klein commercial, sporting a ballet outfit and delivering the ill punch line, “Nothing comes between me and my tutu.”

“If we had the camcorder out, she was ready,” says mother Val, an accomplished pianist in her teaching off-hours (father Mal, a computer consultant, is a singer whose high-school group had a local club following, while older brother Malaney plays guitar, sax, and drums). “I remember when she was interviewed by a local cable network when she was in 10th grade after she’d done [the network soap opera] As the World Turns. She was very clear about her future, even then.” Soon, a role opposite Whoopi Goldberg in Sister Act 2: Back in the Habit brought numerous offers, including the lead in the agit-pop Black Panther biopic Panther, which she turned down.

Now, Hill may not only be the first dominant female rapper (with apologies to Queen Latifah), but pop music’s next important vocalist, integrating hip-hop and R&B in a way that naturally expands both genres. “I’m a real fan of female singers, going back to Dinah Washington and Sarah Vaughan” says Elektra’s Rhone. ‘And this young lady can throw down with the best of them. She’s going to blow everybody’s mind who hasn’t gotten it yet.”

From the moment she discovered her mom’s basement cache of 45s (Gladys Knight, Donny Hathaway), I had soulful visions. “I haven’t slept in my bed since, like, ’86 or ’87,” she confesses. “I got these big-ass headphones with leather cushions and went to sleep on the floor listening to music. I became, like, the musical historian. My family would go, “Lauryn, baby, who wrote that song, that “Hypnotized”?’ And I’d be like, ‘Linda Jones, 1967.'”

More typical of kids in the early ’80s, was also a hip-hop brat snacking on music videos. One minute she was begging mom for fly Filas and fantasizing about flowing like a female Rakim, the next she was transfixed by Simon Le Bon’s hair (“we were down with ‘Rio.’ All that bullshit”). Then her brother’s friend Pras asked if she and her friend Marcy wanted to form a hip-hop group. After Pras’s cousin Wyclef joined and Marcy bailed, suddenly Hill was on the mike, for real. “Lauryn was principally indoctrinated into hip-hop culture by Clef and Pras,” says David Sonenberg, the group’s manager. “But who’s going to argue with her skills today?”

And how threatening is it that a woman is jacking up hip-hop and replacing its sputtering machinery? “Put it this way,” Hill says, clearing her throat and shifting into gender overview mode, “men want to get over—white men, black men, rappers, doctors—regardless. They want to do what they want to do. And a woman sometimes acts as a mirror, so that when a man looks at a woman, he sees himself, he sees how he’s acting and how she’s reacting, and he doesn’t like it…. When men are with other men, they’re not going to question each other. And that’s not just hip-hop, it’s the world.”

Answering suggestions that Jean at times bogarts the mike to her exclusion, Hill says diplomatically. “It’s very important to me that the world see that the Fugees is not just me and two backup singers. Clef loves the stage. and I love to see him open up and let people see what he can really do.”

Lyrically, like Jean and Michel, Hill invokes a dizzying array of references, from childhood games (Colecovision) to nostalgic sorrow (Cochise’s death in the film Cooley High), as well as nodding to all sorts of politically charged figures (Louis Farrakhan, Newt Gingrich). “You reference something usually because its respected or detested,” says the Columbia University sophomore. “Not because you’re a foot soldier but because you want to evoke that power.”

But pop culture is a racial minefield, where references are regularly misinterpreted. This past year, an anonymous caller to the Howard Stern Show claimed that Hill had said in an MTV interview that she would rather see “babies starve” than have white people buy Fugees records. In fact, Hill had only said, in response to a question about her pop success, that she would be happy “selling my hip-hop records to a black audience.” Despite the unfounded charge of racism, the damage was done.

Columbia (the group’s label) and MTV were deluged with calls from angered white kids and parents. “Some asshole obviously twisted what I said because he was threatened by it,” says Hill. “I don’t have hate for anybody. I grew up with everybody and we should all be able to build our own culture,” she says, her voice growing angrily precise. “Unfortunately, in America we have a tradition of not wanting black people to build their own culture.” Of course, a more controversial point might be to suggest that the Fugees speak more intensely to white kids than, say, Pearl Jam. As Hill observes, “That’s when the world starts to come 360 degrees and not just 180. When white kids start feeling what black kids feel, that’s when the powers that be get nervous.”

Wearing a rumpled sweatsuit and gulping a dish of vanilla ice cream, the broodingly handsome Pras Michel is not living up to his rep as a budding Big Willie—Rolex watches, gold rings, omnipresent cell phone. For now, the dealmaking in a limo with Naomi Campbell can wait.

“This is all entertainment,” says Michel, 25, reflecting on the gap between image and reality in ’90s hip-hop. “And gangsta-ism is part of that. But you’ve got to let kids know it’s an act. At the end of the day, Sylvester Stallone and Arnold Schwarzenegger are like, ‘Listen. these are props, that wasn’t a real fire, I live in a mansion, I’m making money.'”

Michel is the Fugees’ soul in the hole, the original member whose underlying, around-the-way-guy manner balances the starchild auras of Jean and Hill. His brotherly affection for Hill is palpable. “I remember when we were doing ‘Ready or Not,’ she was singing the bridge, and she started crying, like, really crying, but she kept on singing. And yo, man, it just hit me in the heart hard…. It was like she was this angel in a cage and somebody, Christ or God, just came and freed her while she was singing.”

In Brooklyn’s Crown Heights, Michel’s fundamentalist Baptist parents banned all things “worldly” from the house, music included. “Haitian families enforce that shit 24-7,” he says wearily. When he was 12, the family—mom a nurse, dad a factory worker—moved to Newark, where Michel attended Vailsburg High (“a real bad ghetto school”) for a year with Jean. But when Vailsburg closed, Michel’s mother sent him to Columbia, a prestigious, predominantly white, suburban public school, described by Hill, a fellow student, as “just like Fame, everybody wanted to be the star.”

Michel shined, eventually scoring 1350 on the SAT and getting accepted to Yale on a bet with his adviser (the wife of infamous baseball-bat-wielding principal Joe “Lean on Me” Clark). “I wasn’t even tripping on Yale,” says Michel. “But I wrote the essay to prove I could do it.” He ended up at Rutgers for two years until the Fugees found success, which his parents (who now live in Florida) have only recently acknowledged.

“They thought I was going to hell with a mike in my hand,” he says, forcing a laugh. “But now, we’re not out there saying, ‘Fuck our parents.’ We respect them. My mom had, like, nine brothers and sisters and she was the only one able to come to America and further her education and do for her family back in Haiti. I respect what she went through for me.”

Wyclef Jean was a child prodigy, but not as a musician. “When I was born I had the gift of the spirit in me, and my father [a Church of Nazarene minister] knew it. Ever since I was little I could take a mass of people and influence them.”

In the late ’70s, when Jean’s family left the dictatorial squalor of Jean-Claude “Baby Doc” Duvalier’s Haiti for the Brooklyn squalor of the Marlboro Houses in Coney Island, Wyclef’s gift, plus a handful of change, got him a ride on the F Train. So he hung around gangs, at one point lifting money and appliances from his parents’ apartment. The apartment itself was a cramped hostel, with as many as 12 different sisters, brothers, grandparents, aunts, uncles, et al., passing through. To keep Wyclef out of mischief, his parents encouraged him to take up music. But when his musical interests strayed to the secular, hip-hop became his calling.

“When Jesus roamed the earth he was barely in the so-called church,” Jean now says. “So when I’m singing or rhyming or whatever, there’s always that connection with God. When people look at the Fugees onstage, I want them to go, ‘Oh shit, something is with that motherfucker.'”

Jean’s family moved to New Jersey when he was 13 and his musical obsession deepened—jazz band, concert band, even maintaining a church band. “Clef was notorious as the king of the Newark talent shows,” Hill recalls. Though he adopted the name MC Nelle Nel (“I had a serious Melle Mel complex,” he admits, laughing), Jean was also intrigued by rudeboy-prophets Bob Marley and Peter Tosh. Setting up shop in his uncle’s East Orange house along with cousin and current Fugees bassist Jerry Duplessis, he experimented with reggae-inflected hip-hop tracks in what became known as the Booga Basement, where The Score was eventually recorded.

But first, Jean did a stint at Long Island’s Five Towns College, a music and business school on Long Island (“they weren’t too excited about some kid coming in there thinking he was Jimi Hendrix”), led the funk band Exact Change, had a minor raggamuffin club hit (“Out of the Jungle,” which soaked up free-Nelson Mandela sentiment), and watched as the Fugees’ demo tape induced across-the-board yawns from hip-hop A&R types. Even manic, live auditions in manager Sonenberg’s Manhattan office drew duh-uh stares.

“I think it was all too much,” says Sonenberg of the Fugees’ presentation. “Clef, I mean, he’s like a cultural ventriloquist who also plays the guitar, Pras was this hard street rapper, and then Lauryn’s singing a soulful version of ‘Imagine.’ These record-company guys probably thought it was some weird stunt. You could see them thinking, ‘Is it R&B or is it rap?’ when they should have been thinking, ‘It’s both.'”

Finally, Ruffhouse/Columbia’s Chris Schwartz and Joe “The Butcher” Nicolo got it. After a production mismatch sabotaged 1993’s awkwardly hyper debut Blunted on Reality, Jean took control in the studio, and The Score resulted. “The way Clef strips things down, like on ‘Killing Me Softly,’ and leaves the sound so open, yet with such emotion, its genius,” says Nicolo, engineer for Schoolly D, Kris Kross, and Cypress Hill. “It works perfectly with Lauryn’s voice. I mean, every A&R guy is dying to reproduce that sound.”

The Fugees are the history of hip-hop’s future. They take the music back to its West Indian sound-system roots, revisit the Sugarhill era of instrumental backing bands, and recombine Run-D.M.C.’s “Rock Box” hard-posing with the conscious innovation of Public Enemy and the Native Tongues posse (De La Soul, Jungle Brothers, A Tribe Called Quest). Animating late-’80s ragamuffin hip-hop, they bring R&B vocal sampling to life, and once and for all, get up in gangsta rap’s face with a righteous, furious wit. For anyone who’s followed hip-hop’s emergence as the most influential pop music of the past 20 years, its damn near stupefying to see that journey so effortlessly condensed on The Score.

But with the Fugees’ commercial appeal, there’s been an inevitable backlash. The contentiously talented Brooklyn rapper Jeru the Damaja recently took some potshots at the group in Ego Trip magazine for covering “Killing Me Softly” (“Fake-ass R&B”) and for reworking the lyrics to Bob Marley’s “No Woman No Cry” (“That’s like blasphemy to me”).

The argument isn’t really over the Fugees’ hip-hop authenticity. Unlike so-called “alternative rap” groups such as Arrested Development and Digable Planets, the Fugees aren’t boho outsiders (“The core audience knows them and believes them,” says Nicolo). The question is whether black cultural expression can be both authentic and universal. Can the Fugees speak to both so-called “inner-city youth” and suburban kids? Can West Indians speak to African-Americans? When will we acknowledge that identities will always be mixed?

“See, you have to remember I have two lives, the West Indian life, and the black American life,” says Michel. “It’s like being the child of an interracial marriage. You’ve got two cultures, two worlds inside you, and that’s what makes the Fugees, because Clef is the same way. Our perceptions can’t help but have more of an edge. We never see things just one way.”

Even Hill’s mom, whose students admire the Fugees and study their lyrics, has faced the issue. “A teacher I work with confronted me recently and said, ‘I know how you raised your family, blah blah blah, how is it that your daughter can relate to ghetto kids? And I was quite taken aback… Lauryn relates because of her humanity. She’s not limited to people who look like her or were raised like her… Why do we think of hip-hop so narrowly? It has to be from the ghetto, everybody’s got to be dysfunctional—who said so?”

A conspicuously blonde voice emanates from a carload of underaged girls with ski-lift tans and more rouge than the law allows. “Are you the lead singer for the Fugees?” I glance over at John Forte, the misidentified Fugee who produced and rapped on several tracks on The Score. Natty in a spotless Nike track suit, Forte shakes a head full of dreads, and smirks, “Is this a trip, or what?” We’re loitering outside the Radisson motel in Park City, Utah, before driving over to Wolf Mountain resort, tonight’s stop on the Smokin’ Grooves tour. Earlier, a different enthusiastic fan had seductively asked a member of the crew, “Hey, you want to come up to my room after the show and drink Jagermeister and play darts?” Welcome to pop music’s wholesome, white underbelly.

It’s hours before showtime, and the Fugees are in ease-back mode — Clef is already at the venue, working on remixes in a mobile mini-studio; Lauryn’s test-driving a scooter Clef just bought her; and Pras is inside the tour bus, busting open a FedEx package of Armani swag. The rest of Team Fugee is in full hustle. It seems the only vice around this group is careerism, from road manager Hassan Shard’s TV commercials to drummer Guillaume’s endorsement deals. Only Wyclef’s brother Sam, lawyer for the Refugee Camp, declines to hype. “No scoop, I’ve got no scoop,” he says, backing away in tabloid retreat.

A recent Teenage Research Unlimited poll surveyed teens about which music acts they were “familiar with” or “liked very much,” and the Fugees topped the rankings, skunking Alanis Morissette by five percentage points, Mariah Carey finishing a tepid third. The Park City crowd bears out those numbers. There’s a high-school-football-game giddiness in the crisp late-August air. And despite my big-city preconceptions, this is no isolated Village of the Mormon Damned. Apparently, the local malls stock loads of Nautica and Hilfiger gear, and everybody’s on their feet chanting “Bonita Applebum” along with A Tribe Called Quest.

The Fugees aren’t hip-hop’s first, or only, band to put on a theatrical live show (see Stetsasonic, Schoolly D, L.L. Cool J on MTV Unplugged, the Roots, Beastie Boys, Goodie Mob, etc.), but they’re both the most choreographed and the most spontaneous. Tonight, Hill’s voice is scratchy and her freestyle rap fizzles, so Clef immediately takes control, playing Busta Rhymes’s “Woo-Hah!! Got You All in Check” on guitar, freestyling in Japanese and French, beckoning for a bass line (Grandmaster Melle Mel’s “White Lines (Don’t Do It)”) or drumbeat (Special Ed’s “I Got It Made”) or record (“Where’s that Beenie Man shit?”) to quicken the pace. Pras moves into the crowd during “Ready or Not,” spreading his arms Messiah-like against the mountainous backdrop. The show is salvaged, in style.

Onstage and on record, the Fugees have a group dynamic previously unimagined in hip-hop or pop—Jean’s one-man-band, son-of-a-preacher-man bluster pushing and reacting against Hill’s self-possessed artistic repose, while Michel dispenses straight-up street poetry in the syrupy baritone of a playground sage. Its a complex mix of personalities that manifests the group’s high-minded ideals.

“Everybody’s upbringing was different, so I don’t point the finger,” says Jean, assuming an almost prophetic air. “Like us Haitians got treated like shit by black Americans because they’d been treated that way. But let’s don’t go backwards, blaming kids for things they had no control over.” He pauses, luminous brown eyes fixing me fervently. “Now, with this music, we have a chance to move beyond all that.”