Summer 2023 is proving to be the “Summer of Wham!” Forty years after the release of the pop duo’s explosive debut album, Fantastic, the Netflix documentary WHAM! took up a slot in the platform’s “trending” strip. That same week, the extensive Wham! collection, The Singles: Echoes from the Edge of Heaven — featuring varied versions of the band’s biggest hits — became available in multiple collectible formats.

Andrew Ridgeley, the sometimes-maligned member of Wham!, is enjoying a renaissance of his own. In 2019, he published his memoir, Wham! George & Me, and recently Wham!’s music has found a brand new, youthful audience on TikTok. The perennial “Last Christmas” hit No. 1 in the U.K. again last year and has topped over a billion streams.

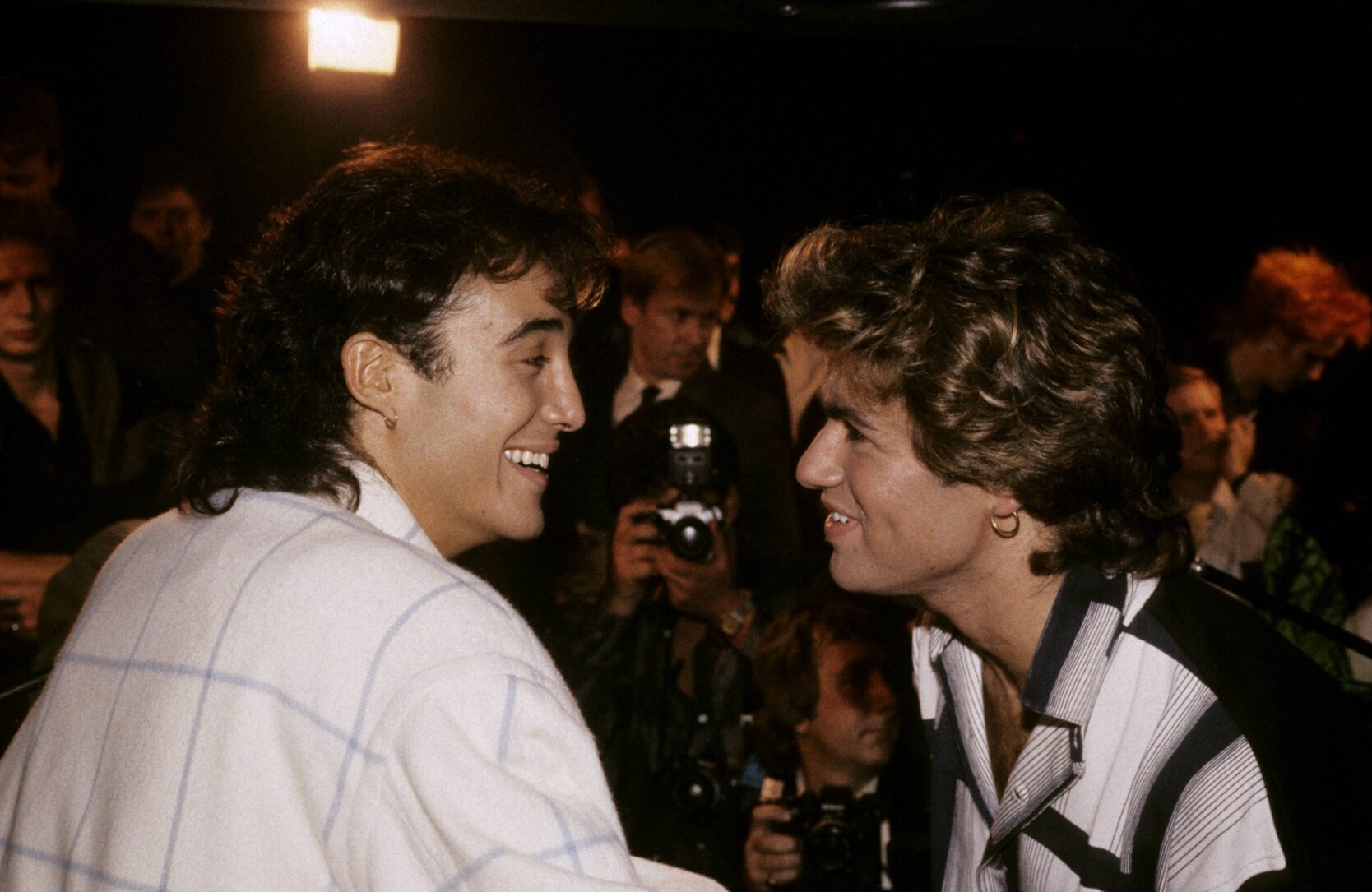

It’s the WHAM! documentary that has put the brightest spotlight on Ridgeley. The film is a charming story of a beautiful and lasting friendship that started when Ridgeley and his bandmate George Michael (né Georgios Kyriacos Panayiotou) met as adolescent schoolboys. Their friendship remained steadfast to their superstardom, culminating in their one-time farewell concert, “The Final,” at Wembley Stadium. They remained close friends until Michael’s death in 2016.

Narrated by the duo, Michael’s input is, in large part, taken from interviews conducted by BBC Radio 1 DJ Mark Goodier. It aligns perfectly with Ridgeley’s present-day commentary. WHAM! is less about music and its creation and more about what made the pop phenomenon the singular entity that it was. It has the guileless and excitement of youth.

Post-Wham! Michael became one of the biggest-selling artists of all time, ultimately disintegrating on a personal level. Meanwhile, Ridgeley has led a seemingly idyllic existence in his long-term home in Cornwall.

In between cycling trips, Ridgeley has been making the WHAM! promo rounds and winning hearts all over again with his natural charisma. Here, he reminisces about his Wham! days with his lifelong friend, whom he still affectionately refers to by his childhood nickname, “Yog.”

SPIN: How did the WHAM! documentary come about?

Andrew Ridgeley: In the wake of the publication of the book, I was approached by Sony Pictures, who wanted to make a biopic. The George Michael estate had no appetite for that. Interest in the book rights and meeting people at book signings made me aware that Wham’s story and its music held a special place in a lot of people’s experiences and affections. Also, we had a 40th anniversary coming up. As the George Michael estate wouldn’t consider a feature film, I thought maybe a documentary would be the way. Whenever Yog went on tour or released records, there was always an element of Wham! legacy in his wake. Legacy is a proactive matter, and I felt that a documentary would be an excellent way of projecting legacy, reaching fans, and giving them more of what they want.

The George Michael estate was okay with a WHAM! documentary being made?

We had a few philosophical obstacles to surmount, but we did. I think maybe the reticence was a consequence of so many unofficial accounts. They were a little skeptical as to whether it would be done in a way that will be acceptable for them. But it was always going to be. They were convinced of that from the fact that Simon Halfon was involved — who is a longtime friend of mine, and also was a friend of George’s. That allayed those fears to a degree. The film was never going to be anything but a celebration of what gave Wham! its unique character. There’s nothing to be fearful about the Wham! story. It’s a story of the best things in life and the most optimistic and positive aspects of life. You can’t make it a gloomy or negative documentary about Wham! It’s impossible.

Was the documentary based on your memoir?

Chris [Smith] said, more than once, [that] he came to the project not knowing anything about Wham! He read my memoir — and I don’t know whether he read Bare or any of George’s subsequent biographies, but he said to me it gave him a template. He saw this fundamental thread, which was our friendship, informed and gave substance to Wham! and the music we made and the way that we saw things. That’s one of the essential attractions of the film is that he frames it in the context of what was Wham!’s perhaps most unique character and that which gave it a personality, which was the friendship that fused it with everything that I think people found attractive.

How come the documentary keeps such a tight focus on WHAM! without getting into you or George before and after?

That was very much my objective, and also perspective, insofar as it had to be about Wham! and Wham! as more than the sum of its parts, not about the parts. Nothing on either side really mattered. Obviously because Wham! is inextricably linked to our friendship, and in many ways a manifestation of our youthful friendship, necessarily the early days of the friendship are in the film. Beyond that, the Wham! story has a beginning, a middle and an end, so it sets its own parameters. It’s an easier story to tell in that context. That’s all it ever needed to be.

The telling of the story through archival content with you and George as the narrators drives the WHAM! story in such a powerful way.

Simon suggested purely archive footage. The home movie stuff, my dad was an amateur cameraman and photographer. He took a lot of cine and stills when we were growing up, in masses and masses, so there was a very rich archive. From the point that we became Wham!, most of it is documented. There are some gaps, and there’s footage that we thought we had, or could find that we didn’t end up getting. But largely, I think there’s enough new footage to give the story real substance and flesh out the account.

Chris’ contextualization of the narration with just George’s voice and mine was a bit of a masterstroke. I had several discussions with Chris. He recognized certain events and subjects that are pertinent to the telling, and then drew the dialogue from those things. He and Gregor Lyon, who edited it, had a lot of materials go through and hard work drawing out, creating, or at least imagining the narration, and then fitting the parts to it. It’s not easy, but he did it very skillfully. A lot of people have said to me that it sounds like you’re in the room with the two of us and it’s a conversation. It’s intimate. That’s exactly what Chris set out to achieve, and he has, in spades. It’s remarkable.

It’s extraordinary how much it feels like a dialogue between you and George finishing each other’s sentences.

The narration can seem like a discourse at times because we saw things so very much the same way. Our recollections and how we recall certain events, we didn’t revise history, and therefore, people can see that, “Oh, crikey, that’s evidently exactly the way it was because both George and Andrew tell the same story.” It’s not like that has to be manufactured because if you go back and look at interviews that we did in ’83 right through, we were saying the same things. Nothing changed. That has an authenticity, and therefore the account itself has real authenticity. It’s authentic to the telling of the stories, authentic to our friendship, authentic to our recollections. People get that openness, and they respond to it.

Yours and George’s senses of humor is another thing that comes through in the documentary.

He had a very silly sense of humor, and he was very funny. That remained always the case. That stupidity and silliness was enhanced. There’s no denying we brought it out of each other. That’s the central theme and pillar of our friendship, silliness and the enjoyment we derived from each other’s company. We made each other laugh.

We have a little cassette as part of the seven-inch vinyl collection carry case format of Echoes From the Edge of Heaven. For the inlay, I didn’t want to repeat the formal photos used in the other formats, so I chose informal photos. I felt those photos really illustrated the bond we had, and the silliness. There’s a photo of us at “The Final,” where evidently something that has made us both smirk. It’s a really natural, informal, un-staged snap. It captures quite a seminal moment that, essentially, nothing had changed at all.

The film highlights how, without you, Wham! or anything that came after wouldn’t have been possible. Does that feel redemptive to you at all, especially when it comes to songwriting?

If people’s assumptions have been altered, if people’s preconceptions have been confounded, then they obviously weren’t paying attention or had missed something. The writing credits have been there since 1982 for “Wham! Rap” and “Careless Whisper” and “Club Tropicana.” Maybe people just didn’t believe it. George talking about the writing of “Careless Whisper” as it was worked up over the course of months, perhaps people thought, “Oh, crikey, well, it was a collaborative effort.” That may confound other people’s misconceptions, but only validates that which I know. That would have been a big ax for me to grind over 40 years. It wouldn’t have even been a hatchet now, or a butter knife.

There is a marked contrast in yours and George’s confidence levels, and it’s illustrated by one of your standout statements in the film about how you always knew who you were and one of George’s standout statements about how he was trying to be you.

He said that, not me. You look at the photos of the two of us at 19, and then you look at the George Michael that strode onto Wembley Stadium stage and the transformation is one, complete, and two, incredible. His sexuality was something that compromised him in some ways, but he had reached a point of confidence in himself as an artist and a person. He deconstructed the persona in order to fulfill his ambition. There was still an element of him that was Georgios Panayiotou, but he had assumed the confidence of the George Michael persona, and it allowed him to flourish.

Do you feel your backgrounds with immigrant fathers from different parts of the world and your upbringing had an impact on your personalities?

That’s an interesting point. Part of the reason I was able to say that I knew exactly who I was is because I was Andrew Ridgeley. My dad had changed his family name from Zachariah to Ridgeley. As kids growing up in 1970s England, there was no question mark over whether I was English or not. My name is English. I was English. For Yog, that was different. He never said it, but I think he intimated it in the things he said about his lack of confidence. A kid growing up in ‘70s, England called Georgios Kyriacos Panayiotou, that’s not easy. How do you fit into English culture with a name like that? Everything around you is Elton John or David Bowie or Freddie Mercury.

With 40 years of hindsight, is there anything you would have done differently?

I regret not touring “The Final” and not giving our fans the opportunity to say goodbye. I thought we were under an obligation to them, but I also understood Yog’s rationale that there is only one “final” concert.

If I were advising the younger AJR from this point in time, I’d be saying, “Don’t completely walk away from songwriting. Work at it, and you never know. You’re not utterly without talent. It’s work and you need to work. Everyone needs to work.” George needed to work. Me being feckless and lazy, I didn’t.

I don’t know that I would call you “feckless and lazy.” You are “content and realized.” You don’t seem to have any resentment or a chip on your shoulder.

I never had any resentments. I didn’t have chips. We never fell out over Wham! We had some serious conversations along the way about how we were going to achieve what we wanted to achieve, but it was never going to come between us. Neither of us created a band for glory or fame or celebrity or money. We did it because we wanted to write songs and perform them and, God willing, one day record them. That was fundamentally all that mattered. As long as we were doing that, then things were hunky dory. I never thought I was owed anything that I didn’t have.