2020 was challenging for Lucinda Williams. The three-time Grammy winner—also named America’s Best Songwriter by Time—had a stroke that impaired her left side. If that wasn’t enough, a tornado damaged her home in Nashville. Williams spent months rehabbing, relearning everything from scratch, including how to walk.

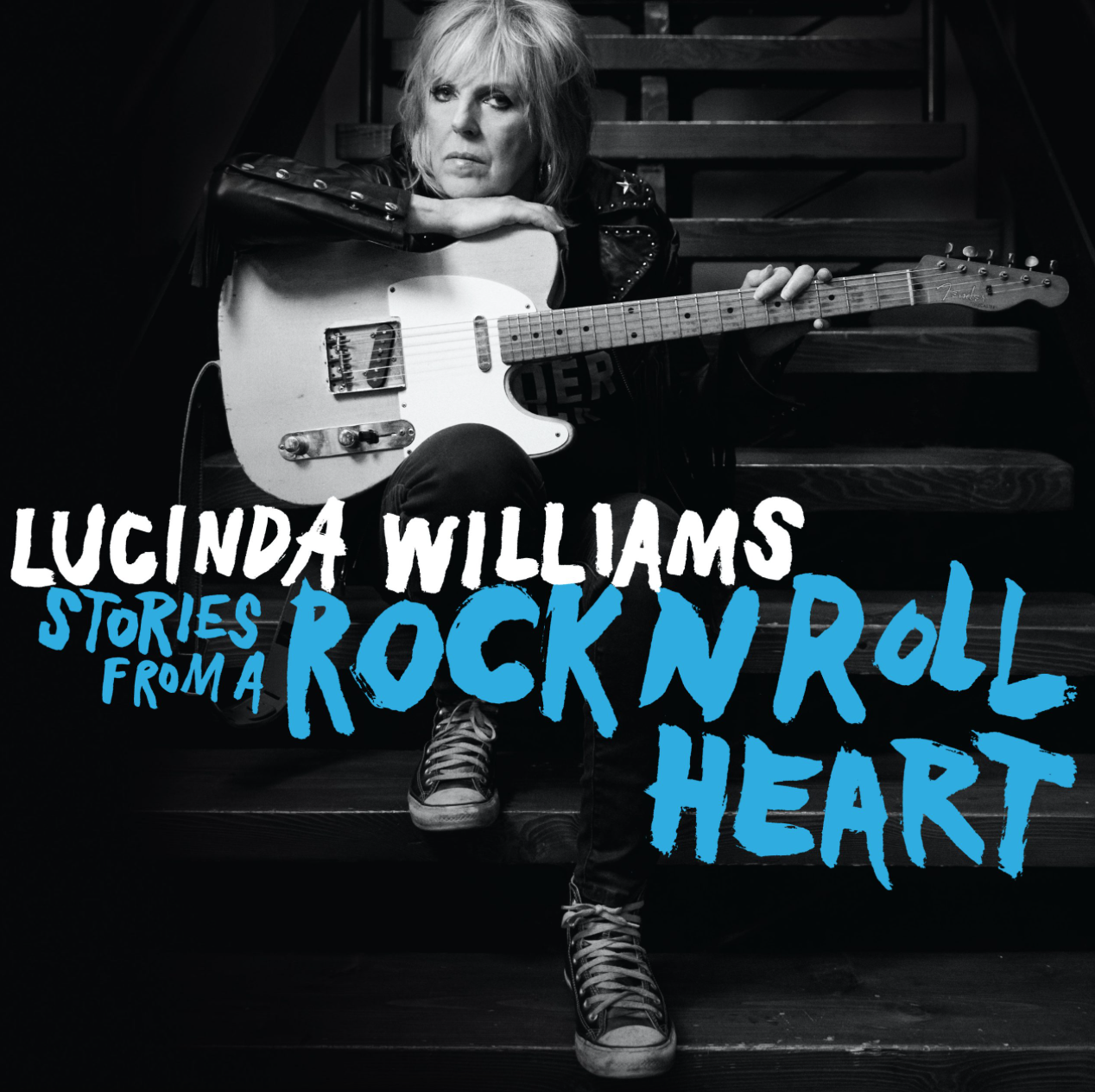

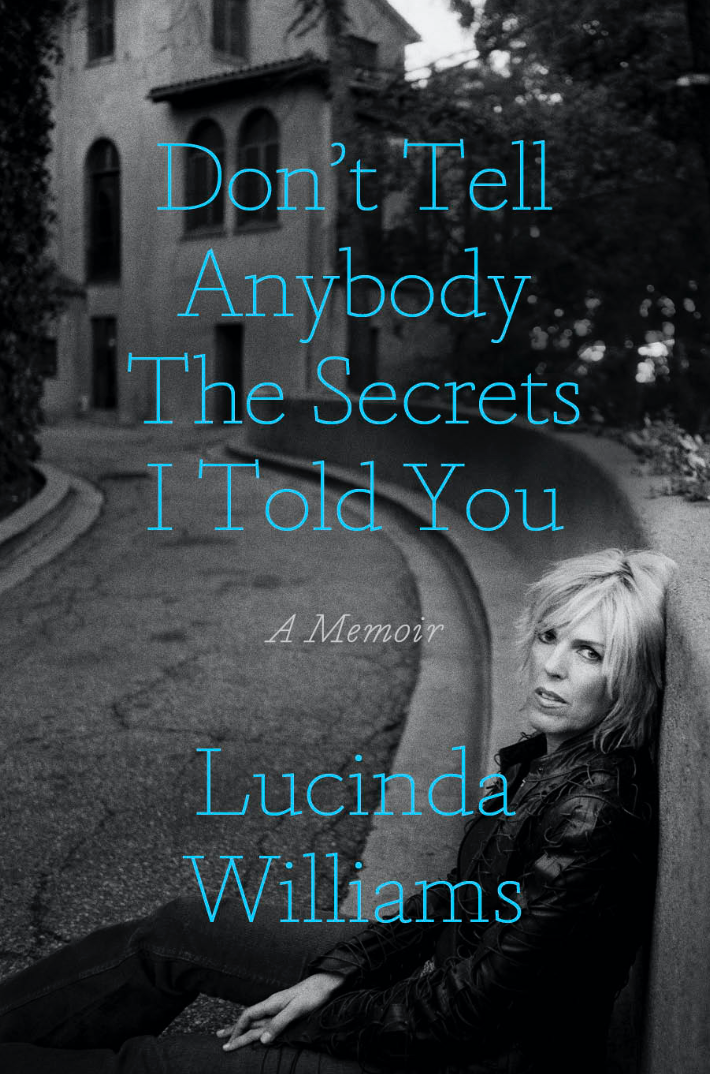

Three years later, Williams is back with a vengeance. This past April, the 70-year-old singer-songwriter—considered a national treasure by her contemporaries—published her memoir, Don’t Tell Anybody the Secrets I Told You, which hit No. 5 on the New York Times bestsellers list. In June, she released her 15th studio album, Stories from a Rock n Roll Heart, which has collaborations with Bruce Springsteen, Angel Olsen, Margo Price, and Jesse Malin, among others. The album features a dream team of pedigreed musicians who have played with everyone from Stevie Ray Vaughan to Dolly Parton and is co-produced by Ray Kennedy, whose relationship with Williams goes back to her seminal 1998 album, Car Wheels on a Gravel Road.

Perhaps Williams’ most valuable collaborator, and most unexpected for her, is Tom Overby, her husband-turned-manager-turned-co-producer-turned-co-writer. Overby stepped into the co-writer spot on Williams’ Grammy-nominated 2020 album, Good Souls Better Angels. On Stories from a Rock n Roll Heart, Williams allows outside input even more. She is, as yet, unable to play her guitar, but in the process of working with other creatives, Williams has expanded her songwriting. Her signature storytelling comes through stronger than ever.

Williams’ resilience is tangible, even in this remote interview. When she speaks to me for SPIN, she is wearing a black T-shirt with the statement “You Can’t Rule Me” in bold, white, all capital letters. That’s an understatement.

Did not being able to play the guitar impact your songwriting?

I still work on lyrics. Thank God I can hold a pen and write with my right hand. With the guitar, I play chords and try to find a melody in my head at the same time. The guitar helps set off the melody ideas. Without the guitar, it’s definitely harder.

It led to collaborations with other people to get the songs done, which ended up being a positive experience.

As a musician who has been self-sufficient for the majority of your career, how did it feel to have to rely on others to get your songs over the finish line?

It can feel like your space is being invaded. It has to be the right person. It turns out my husband, Tom, had been into creative writing long before we met, which was a surprise to me. It’s not something he ever talked about. He’s real smart. He’s one of those brainy types. That’s what attracted me to him to begin with.

It started with…I would be sitting working on a song, and he would think of some stuff and come up with some ideas and write some lines down and shyly hand them to me, and he would say, “I just got this idea for something. You don’t need to use it if you don’t want to, but I just wanted to show it to you.” At first I thought, “What if I don’t like it?” But they were good.

Did the fact that you had already broken the pattern of working entirely solo on the last album—when you didn’t necessarily need to–make it easier to do it for this album, when you actually needed the assistance?

Yeah, definitely. It wasn’t just my husband. It was also Jesse Malin and Travis Stephens, who is also our tour manager. Everybody jumped in, and it was fun. Having so many people involved is not something I would necessarily have said I wanted to do. But then I thought about Tom Waits and his wife, Kathleen, because they write together, so that made me feel better about it. At first, I was a little shy about telling anyone that I’m writing songs with my husband. I didn’t know what people would think. But as I said, the whole thing was a real organic process. It happened naturally.

How did the Bruce Springsteen collaborations on “New York Comeback” and “Rock n’ Roll Heart” come about?

Tom, my husband, said, “Wouldn’t it be great if we could get Bruce on this song?” There was a time when that would have been like, “Oh yeah, right.” But Jesse Malin—who knows everybody in New York City; he’s been called the unofficial mayor of the Lower East Side because he’s one of those movers and shakers—he said, “I think I can probably get a hold of Bruce for you.” And sure enough he did. He got in touch with Bruce’s people and got the message through to Bruce. Bruce knew who I was and was familiar with my music, and he, and his wife, Patti Scialfa, also, said yes. We sent them the tracks. We didn’t tell them what to do. They went into a studio and improvised. I still get excited about it every time I hear his voice on there. He’s so sweet. I’m such a fan. He’s so handsome and cool and such a great artist.

You have two songs about artists who have passed away, Tom Petty and Bob Stinson. Why those two in particular?

Tom, my husband, brought “Stolen Moments” [the song about Tom Petty] to the table. Usually, if he had an idea first, I would look at it, mess around with the lyrics, and come up with the melody and the arrangement and everything. But he got that idea and it grew into this other thing. I kept thinking, “What is this song about exactly?” I wasn’t familiar with the phrase “stolen moments.” This is part of collaboration. It made sense to him, and I had to find out how it made sense. Tom Petty asked me to do his Hollywood Bowl shows with them. That was a huge deal for me. And then he was gone. I’m still grieving him. I wish I’d been able to write with him. That’s what “Stolen Moments” is about. Those feelings that come unexpectedly.

“Hum’s Liquor” [the song about Bob Stinson] was Tom’s contribution too. Tom’s from Minneapolis. He was living in an apartment downtown, and he could see Hum’s Liquor from a window in his apartment. Every morning, without fail, at about a quarter to 10, like clockwork—he said he could have set his watch to it—he’d see Bob Stinson walking to the liquor store. Every single day at the same exact time. That’s what that song came out of.

How did you come upon the topics you speak about on the album?

Topics just come to me. That’s the beauty of being a songwriter. I could hear somebody say something and think to myself, “Wow, that’s a good line,” and write it down so I don’t forget it, and then that’ll show up in a song somewhere. Or I might be watching the news and get real affected by a story. It’s in your face. It’s hard to ignore. The good thing is, I’m not at a loss for ideas, and that’s the first step when you’re writing songs.

Some musicians say the songs are already there; they’re just the conduits. Is that how you feel?

That’s it. I love that you’re saying that because one of the songs on the album is called “Where the Song Will Find Me,” and that’s what it’s about: being ready for the muse, because it does kind of just go through you. At the risk of sounding all “woo-woo” about it, a lot of times, you don’t know where it comes from. It’s hard to describe because it’s so ethereal.

Was music therapeutic in your recovery from your stroke?

Yeah, absolutely. Let’s bring back the clichés. Let’s own those clichés everybody’s so worried about. I was really fortunate to get into physical therapy right away. I didn’t want to slow down. At first, I couldn’t walk across the room without falling down. They had me try a cane. They had me try a walker. That’s when I went, “Okay, that’s it. I’m not going to walk around with this goddamn walker, lifting it up going, “you kids get out of my yard!”—that stereotype. I kept imagining this old woman trying to walk down the street. People always tell me, “You’re so strong and brave.” But I’m just stubborn. It works for me.