Sitting outside of Tartine Bakery on a Thursday afternoon, Lucero’s Ben Nichols and Brian Venable stand out like a couple of blue-collar Southern sore thumbs among their Hollywood surroundings. But after a quarter-century touring the world, they’re used to not fitting in.

When you’re the nation’s deepest-seeded country-punk band drawing fans from both genres (and both political parties), you’ll find fans in most corners of America — but no one location will ever be a perfect fit. They can sell out mid-sized venues from Portland to Biloxi, yet they’ll never rock hard enough for the punk crowd, nor be country enough for the rednecks. But a dozen albums into their career, that’s never stopped (or even slowed) Lucero.

“We’re all raised in the South, but Brian and I met going to DIY punk shows in Memphis and Little Rock,” Nichols says, pointing over to Venable. “It’s funny, because we both love the standard punk rock sound that was happening in the mid-90s, but we just wanted to do something a little different. When the band started, we started rediscovering all the music that we grew up on — Southern rock, classic rock, country. So we said ‘Let’s just put it all in a big bucket and mix it all together.’”

On February’s Should’ve Learned by Now, the band churned out exactly what fans have come to expect: 10 tracks that blend a punk rock attitude with the earnest storytelling approach of country music, all delivered by their usual blend of guitars, drums, keyboards and Nichols’ whiskey-soaked vocals. While the consensus might be that the album’s more straightforward rock ‘n roll song structure and narrative are a “return to form” or a throwback to the early days of the band, Lucero’s return to simplicity can be viewed as a part of the band’s near-circular evolution.

In 25 years, Lucero has gone from releasing albums on its own to indie labels to a major like Universal then back to indies and now on their own— with some albums bringing in full horn sections, pedal steel and guest stars while others strip things back to a “home recording” sound. But in some ways, that inconsistency has allowed Lucero to embrace the ultimate consistency of being a veteran band with a devoted (if unusual fan base) and the freedom that comes along with it.

“Nobody expected us to still be a band at this point — definitely not us — but we just kept going,” Nichols says in his signature gruff voice. “We really didn’t want to get real jobs, so it made sense to just keep making records. We’re still having fun doing it.”

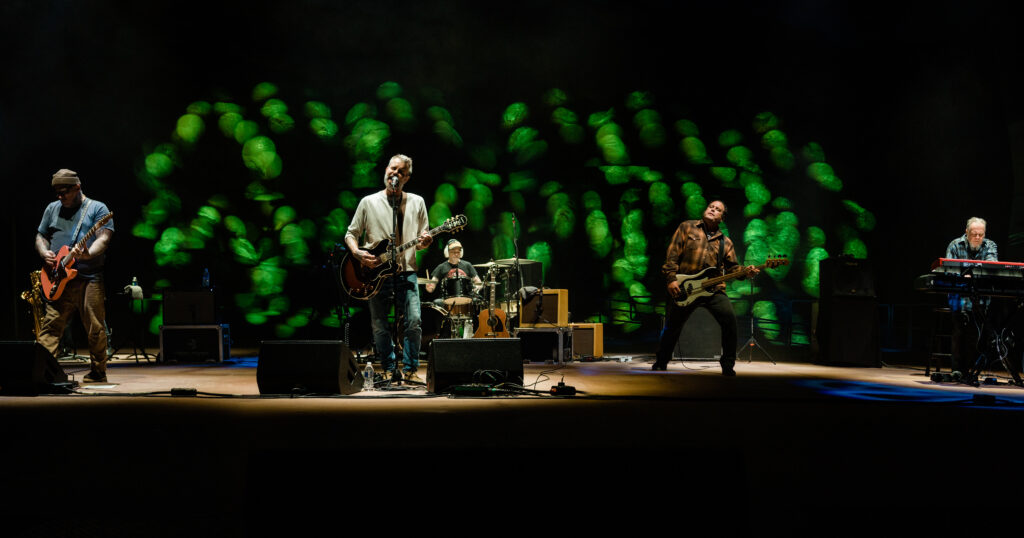

While Nichols is quick to point out that Should’ve Learned by Now isn’t the deepest or most thoughtful album Lucero has ever made, it’s arguably what they do best. Comprised of tales of cigarettes (“Slow Dancing,” as one of many examples), relationships, diners (“Here at the Starlite”) and whiskey (“Sixes and Sevens”), the latest album explores the same themes that brought them an audience in the first place, rather than the slightly more complex topics of some of their recent work. And while they’ve never had the big radio hit (although they’re not ruling out an old song taking off on a Netflix show, since Nichols had his most widespread solo song, “The Last Pale Light in the West,” appear on The Walking Dead), their stories of late-night drinking and the heartbreak that often goes with it have turned albums like Tennessee and That Much Further West into cult classics. Nichols and his longtime bandmates — Venable, drummer Roy Berry, bassist John C. Stubblefield and pianist Rick Steff — are perfectly content to see Lucero slowly grow from dive bars to theaters over the decades (even as they see their openers sometimes take off in popularity).

“We realized early on that we’re not the type of band that’s made to have a big break,” Nichols says. “But the funny part is that we play festivals with bands that no one’s heard of called things like Franz Ferdinand, and then three weeks later, they’re selling out stadiums. We just did a tour with Morgan Wade, and now she’s blowing up. We’ve had a lot of great bands open for us and then get their big break. But a long time ago, I reconciled myself to the fact that we can continue to grow, but it’s not going to be that traditional rock ‘n roll big break moment. I think it would make me nervous if it ever did happen. I can’t handle that.”

Although plenty of bands may fake humility in saying that they don’t want to blow up, Nichols is genuine in his concern. He never wants to be in a position where Lucero owes money to industry folks like labels or management — which isn’t a problem for a blue-collar working band. But his bigger concern is that he’s not a fan of massive stages. The vocalist likes to watch the opening acts from the crowd and interact with the attendees. He likes to hear the shouted requests and hit venues in places that get ignored on the near-constant touring schedule Lucero has maintained for 25 years. During that run, they’ve hit festivals, opened for Social Distortion, and pulled off unconventional headlining shows — like a run in 2015 where they performed two sets at each individual show (one consisting of slow songs and another of plugged-in rockers) rather than having an opening act.

“Lucero has this split personality where we like loud rock ‘n roll songs, but we also like really quiet pretty songs,” Nichols says. “Doing those shows, we got to compartmentalize both, and it made a lot of sense to me. I didn’t have to worry about how to transition from one song to the next and try to make a setlist that flows just right. I could just put all the sad songs here and all the dumb fast songs over here.”

That diversity in their catalog also means that a Lucero show in one city might be full of cowboy hats, while the next is all battle jackets. But more often than not, their audience is a hybrid of cultures that would almost never be seen otherwise interacting. At a time when the country is as politically and culturally divided as ever, Lucero shows serve as the United Nations of American music — somewhere that anarchist punks, liberal progressives and the most diehard of republicans can put their differences aside and sing along.

“You might not want to talk politics at a Lucero show,” Nichols laughs. “You’re gonna have the whole spectrum present. I’ve got my thoughts on stuff, but we’ve never been a political band. I’ve avoided that intentionally. I’ve thought ‘Maybe I should sing songs about politics…’ but I just don’t enjoy it. For better or worse. Lucero is what it is. You can have people of all different perspectives in one room, and hopefully everybody has a good time for a couple hours having a couple of drinks and watching me make a fool out of myself. Sometimes, you’ll even get a really good rock ‘n roll show.”

Aside from the absence of politics, Nichols says the only thing he’s really ruling out from a songwriting perspective is the type of complex, high-concept album you might see from a prog band. Otherwise, Lucero is always open to mixing up their genres (particularly within their country/Southern rock/punk wheelhouse) and experimenting with new sounds or ideas. Nichols’ lyrical storytelling adapts to the project regardless of genre, and he’s willing to see how it sounds in a vast array of contexts — a mentality he’s adopted from one of his songwriting heroes, Bruce Springsteen.

“Stylistically, it’s not necessarily a straight line in any one direction,” Nichols says. “One of the good parts about Lucero is that we don’t have any rules about genre. Now, this might not have helped our record sales — as refusing to conform to any label has maybe slowed us down a little bit — but I can make any record I fucking want to make with whatever instruments I want to make. And I know that most of our fans will come along with us just for the hell of it.”

A lot of bands would be milking their 25th anniversary and the ongoing 20th birthdays of some of their signature albums. Lucero prefers to focus on the future. They’ve made up for the poor quality of some of their early LPs by doing re-releases for albums’ recent anniversaries, but they’re otherwise just glad to still be alive and making music.

“I’m proud that I can sing songs I wrote 25 years ago and still stand behind them,” he says. “It’s evolved over the years, but no matter what stylistic direction we’ve gone, I’m very happy that the core songwriting has stayed pretty consistent over such a long period of time. I’m also just glad we’re still alive because it’s insane how many times we should have died over the years. Everything we got away with as kids was a little ridiculous. I was 24 when the band started, so I’ve been in Lucero longer than I haven’t been in Lucero. Holy shit.”