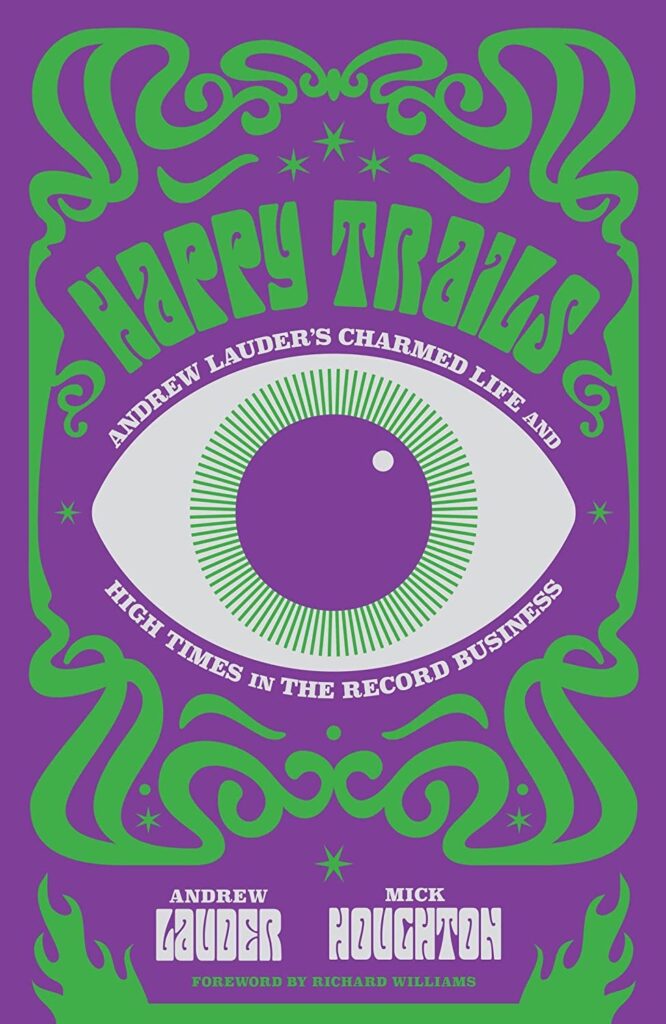

Music executive Andrew Lauder’s tale is a classic one: young and naïve country boy who came to the big city, fell into a random, entry-level but opportune position at the publishing company Southern Music, and went on to make his mark in the industry for half a century. During his tenure at various music companies in the UK–including Liberty Records, United Artists and Silvertone–Lauder released key albums from Elvis Costello, the Stranglers, the Buzzcocks, Hawkwind, Can, Neu! and the Stone Roses. At 75, Lauder has collected his storied years in Happy Trails: Andrew Lauder’s Charmed Life and High Times in the Record Business, co-written with longtime music scribe Mick Houghton.

Happy Trails is a book for music historians and crate diggers, particularly lovers of the blues from the ‘60s through to the ‘00s. More of a trainspotter’s timeline than a narrative or even a biography, there is no point in combing these pages looking for salacious rock ‘n roll stories—although there is a particularly delicious (if restrained) chapter about his experiences with Chris Blackwell during Lauder’s brief time at Island Records. (Also fun is his anecdote about meeting Johnny Cash and June Carter.) Instead, Happy Trails is a behind-the-scenes basics of releasing music, which is not as sexy as it might seem to the non-industry fan.

Still, it’s pretty exciting to hear Lauder talk casually about his youthful days at Southern Music on Denmark Street in London’s West End where, on an everyday basis, “I was rubbing shoulders with the likes of Donovan, Reg Dwight, Ronnie Wood and David Bowie, Mike Vernon who was producing John Mayall, and very soon Fleetwood Mac, or Rolling Stones manager and producer Andrew Oldham.”

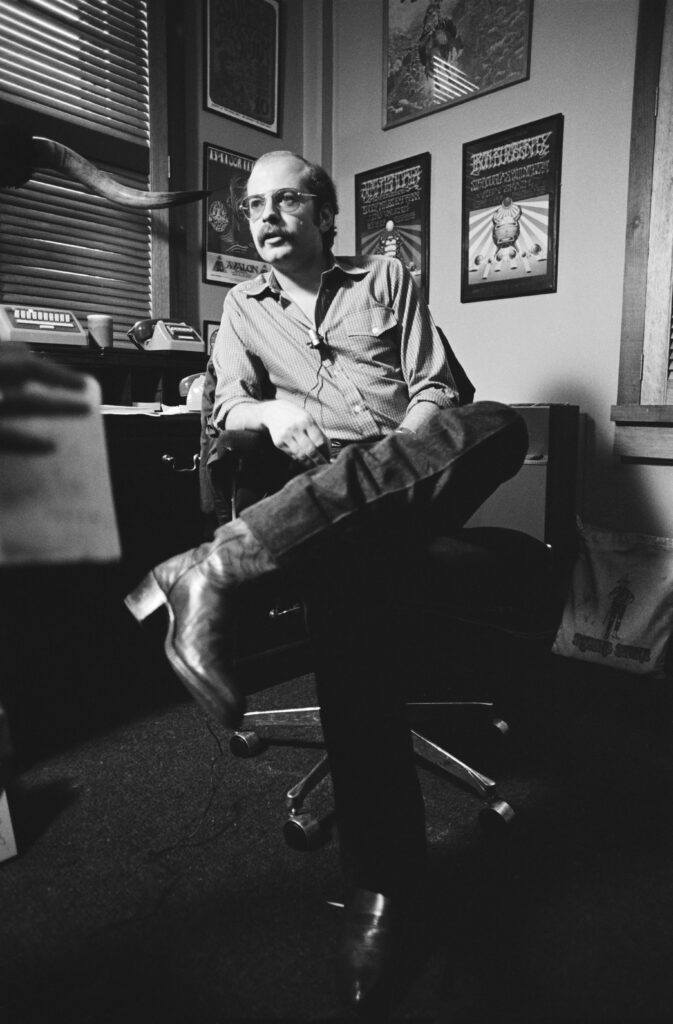

From his home in the British countryside where Lauder is living his best retired life, he traces some of his most memorable hits and misses for SPIN.

You missed the Beatles rooftop performance, and you didn’t stop to watch Tina put the Ikettes through their paces. Which of your “if I had to do it all over again” events do you wish you could have experienced?

With the recent death of Tina Turner, I wish even more that I’d stuck around to watch her rehearsing the Ikettes, but I probably would have been asked to leave anyway. If I could go back in time, there’s no way I wouldn’t choose the Beatles’ rooftop performance. It’s arguably the ultimate “you should have been there” moment in rock ‘n roll history. The fact I was invited along and said, “No, I’m too busy” because I had a couple lunchtime meetings now seems like a moment of complete madness. Our offices were only a block or two away from the Saville Row building. I did open the windows, but never heard a thing. It’s so galling because I only have to see those very familiar images of the Beatles on the rooftop to start kicking myself again.

Pre-internet, putting ads in music papers was the genesis of a lot of landmark music figures, partnerships and bands in the UK. Tell us about bringing Elton John and Bernie Taupin together during your time at Liberty Records?

It was Ray Williams who put an ad in the New Musical Express in June 1967 that simply read “LIBERTY WANTS TALENT” and he got a sea of responses. Among these were letters from Reg Dwight–soon to become Elton John–and Bernie Taupin. One described himself as a singer/pianist who couldn’t write lyrics, the other said he could write lyrics but couldn’t play music. Pre-teaming with Bernie Taupin, Liberty had turned Reg down after recording demos with him.

What were your early impressions of Elton John?

When Elton wasn’t out on tour with his band Bluesology, he was employed in the trade department at Mills Music across the road from Southern. I sometimes had to take packages of sheet music to the post office in Soho. Elton did the same job for Mills Music. We’d be racing along Denmark Street, dragging a railway porter’s trolly behind us, trying to catch the last post. Elton was always really friendly and hugely knowledgeable about music. Even after signing to DJM, he was still working at a record shop called Musicland part-time. I used to go in there at the end of the week because that’s when the imports came in from America. Elton knew what I was into and would put them to one side for me.

You had some of the earliest Lemmy experiences in the industry. What is the most memorable?

Lemmy had been playing in various bands and working as a roadie, including with Hendrix. He was the last and most crucial part of the jigsaw when he joined Hawkwind just as they were fully developing what became their trademark “space rock” sound which traded on spectacular lighting and magnificent artwork courtesy of genius designer Barney Bubbles. When Lemmy joined Hawkwind, he’d never played bass and his unique style came from having been a rhythm guitarist which gave Hawkwind that pulsing, propelling drive as a live band. He added a wild, rock-biker presence that grounded the band. Both on stage and off, his image and personality made him a natural frontman—however much Hawkwind was very much about the sum of all its parts. When we recorded “Silver Machine,” which was originally sung by the band’s resident poet Bob Calvert, it was manager Doug Smith who suggested Lemmy should take over the vocals. It was a massive hit that effectively pushed Lemmy even further to the fore. He became very much the figurehead for fans and the media. That didn’t sit well with some of the band and would ultimately contribute to his being ousted.

You released the first records from seminal groups Can and Neu!. What are some key memories you have of the music and those two groups?

The first Can album, Monster Movie, was the only album they made that you’d class as a rock album. The first time I heard it [it] totally blew me away. They evolved in a much more experimental–some would say challenging–direction after that. Can’s music was hugely influential, though not so much at the time we released their albums between 1970 and 1975. Albums such as Tago Mago, Future Days and Ege Bamyasi were seized up by the post-punk generation. Can set the tone for experimental music in the ‘80s. Neu! brought something else to the party with their pulsing, hypnotic drive, repetitive drones and rudimentary raw vocals.

At the time, none of these albums sold at all well. They even confounded most critics. They baffled people because they sounded nothing like any American or British bands of the day. That was the appeal to that post-punk generation. Can and Neu! provided an antidote to prog and pretentiousness.

Being “The man who signed Can” has become something of a calling card for me. In truth, I only licensed their LPs from the German office but [at the time] no other label in Britain was conspicuously releasing much coming out of Germany.

You mention a few bands you missed out on including Motorhead, King Crimson and Roxy Music. Who is the ultimate “one that got away?”

I could have signed Queen, but I simply didn’t like them at all. It wasn’t my kind of music and—not just in hindsight, I did think they’d be successful. Maybe not that successful; not that it would have made a difference. I could never sign a band I didn’t like.

Motorhead are “the one that got away” and even more so because we had them signed to the label. I loved Lemmy’s idea of wanting to form the loudest, dirtiest, nastiest rock and roll band in the world. He put the first trio together within weeks of leaving Hawkwind, but they weren’t ready. It was a brilliant idea on paper that it hadn’t been thought through and I made the mistake of putting them into the studio at Rockfield too soon. I thought Dave Edmunds would knock them into shape, but he only recorded four tracks before he bailed out to do his solo album for Led Zeppelin’s Swan Song label. Without Dave in control, the rest of the recordings sounded like demos. Lemmy hated them and he made me promise never to release them. He then brought in a new guitarist and drummer in what is now accepted as the classic Motorhead line up which made all the recordings we had in the can pretty much void.

Plus, Lemmy was taking up more and more time because his manager had left. So Lemmy was in and out of the office all the time and quite a handful—no surprise there—so I let them go. And of course, they eventually got the sound right and were able to slot in somewhere between punk and metal—appealing equally to both sets of fans. Inevitably, United Artists did release the original album On Parole, but I’d left by then so I never broke my promise to Lemmy.