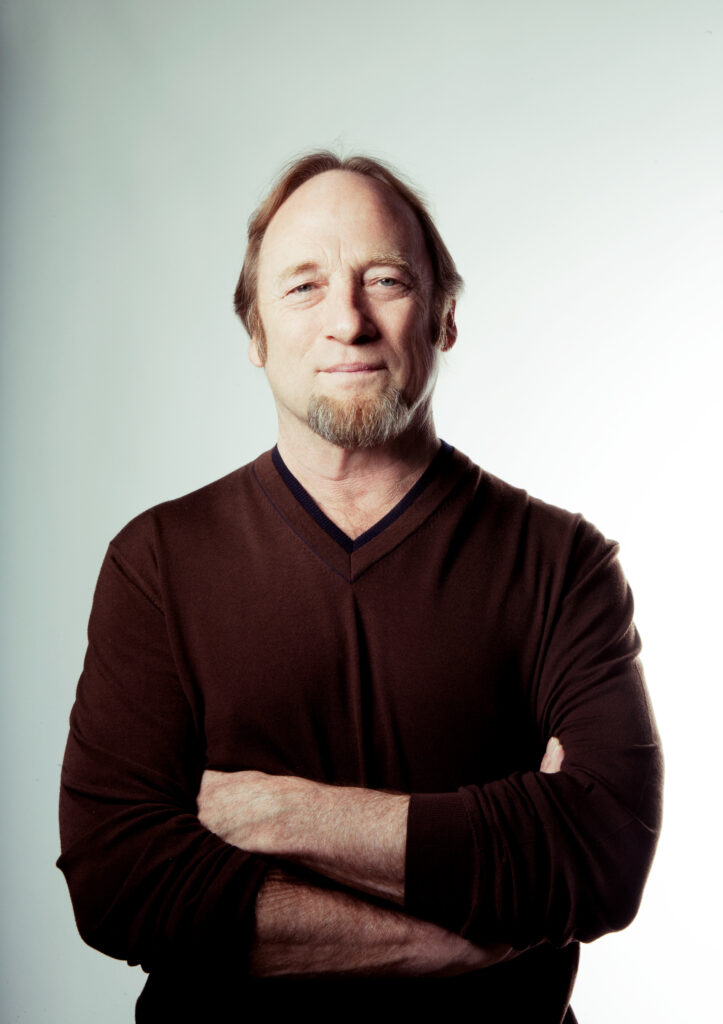

It’s been an eventful year for legendary songwriter Stephen Stills, in both good ways and bad. The bad struck like a lightning bolt in January when Stills’ longtime friend and collaborator David Crosby died after a sudden bout with COVID-19.

“He was a magical person,” Stills says over Zoom as he reminisces about his late friend. “I can’t tell you the number of recording sessions that he absolutely wrecked by him going off on standup in the studio. We couldn’t get through a take! You remember the scene in Bohemian Rhapsody where they all knocked the baffles over? Well, we did that so many times because of Crosby making us laugh.”

Though their relationship had its fraught moments over the last decade, things were in a positive place at the time Crosby died. The two men had been creatively estranged since the functional end of Crosby, Stills and Nash after a gig on the White House lawn in 2015. Fortunately, they had a chance to reconcile in person, post-lockdown in 2021, but under somber circumstances. Both men attended a funeral service for their bandmate and keyboardist Mike Finnegan, who succumbed to liver cancer.

Crosby was rehearsing for a new tour with his solo band at the time of his death. He even planned on bringing Stills’ son Christopher on the road to play guitar with him. Then one day, he took a nap and never woke up.

But as some longtime friendships have recently come to an end, perhaps the most enduring musical partnership of the 78-year-old guitarist’s life is still going strong. In April, Stills and his wife Kristen organized the sixth iteration of their Light Up the Blues benefit concert at the Greek Theater in Los Angeles to benefit Autism Speaks. Musical guests like Joe Walsh, Willie Nelson, and Sharon Van Etten were well-received that night, but the energy in the room shifted when Neil Young ambled out and began to play.

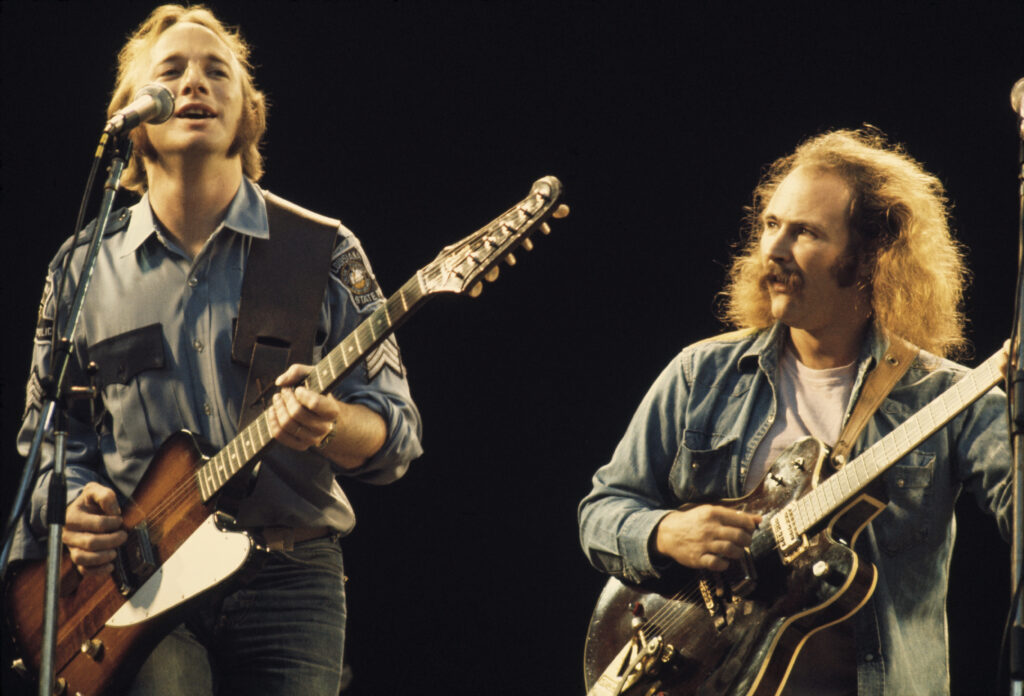

Stills and Young have been swapping riffs and solos for going on nearly six decades now, but it hasn’t always been easy. Their seemingly unbreakable bond was cemented during sweaty Thursday nights in the mid-1960s, jamming onstage as part of Buffalo Springfield at the Whisky A Go-Go. Even after the Springfield went up in flames not long after Monterey Pop in 1967, their friendship lasted. Somehow, they managed to survive the subsequent mayhem and mania that defined the existence of CSNY throughout the 1970s. They even endured as the Stills-Young Band for a short time after that, though that collective moniker might be due for an update.

“I think at this age we’re going to call it the Young-Stills Band,” Stills jokes. “We decided that years ago. It’s like, first, we call it Stills-Young, but when we get older, we’ll call it Young-Stills, and Bob’s Your Uncle.”

Outside of a quick, two-song acoustic set at a protest rally in Victoria, British Columbia, Light Up the Blues was Young’s first major public performance in years. “The whole thing was really neat, and evolving the set was fun too because I was electric and Neil was acoustic,” Stills says. “The obvious thing was to have Neil go first, which he did. And then we sang together. Then I went for three by myself and with Joe Walsh. Then Neil came back, and then we played more together. So, Rolling Stone of course characterized that as an 11-song Neil Young set.”

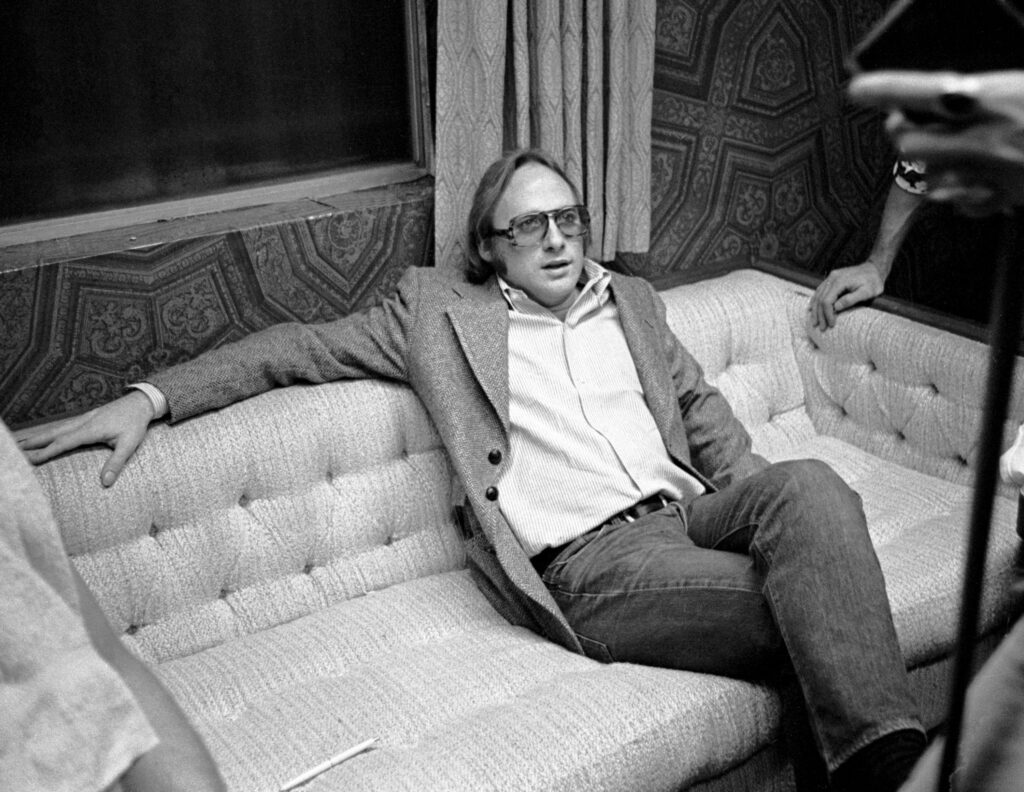

Stills has always been someone eager to work out new musical ideas. That was especially true in the early 1970s when he was releasing solo records, contributing to supergroup projects, and forming new bands seemingly out of thin air. The breadth of his work during this period really comes into focus on the newly released Live at Berkeley 1971. Accompanied by the iconic Memphis Horns of Stax Records acclaim, Stills blasts his way through some of the best material of his career in front of a rapt Northern California crowd. There’s even a brief and stellar cameo from Crosby, who sings on “You Don’t Have To Cry” and “The Lee Shore.”

I recently had the opportunity to speak with the man they call “Captain Many Hands” to talk about some of his old friends, his new live record, and how he’s handling life following his own two-time struggle with COVID.

SPIN: How did it feel to play the Light Up the Blues event last month?

Stephen Stills: Warm and fuzzy. It was like it always is with Neil after an absence. We’re really glad to see each other and played really well together.

You’ve played with each other for decades. What’s the chemistry like between you both at this point?

Well, we went out to dinner about six weeks before and mutually admitted it was time to knock off the rust from COVID. We rehearsed. We actually got into my studio and went through songs and did some deep dives. There were a couple of mishits, but that’s okay. There was one song called “Everybody’s Wrong” that’s really profound. But just like the original Buffalo Springfield recording, we missed the track by a mile. We kept fiddling and I came up a zany idea to do a banjo – which I really can’t play — but it was comic relief and it actually sounded really good.

It sounds like it was a fun process.

We were discovering all those old songs and playing together. At first [Neil] didn’t want to play electric at all, but I got him to. The whole night is such a blur for me because every time I’d leave my dressing room there would there’d be staffers with 20 questions.

Are there any moments that stick out?

The highlight for me was “Wooden Ships.” I thought we just killed that. And having [David Crosby’s son] James Raymond there … nobody knows this, but he sounds just like Crosby when he sings. And so when we rehearsed it … I don’t grieve over the top, but there wasn’t a dry eye in the rehearsal room. I couldn’t get through the song. Unbelievable. And then on the night, it came off really good. Christopher [Stills] was just, of course, himself. Tigger. That’s his nickname. Tigger.

How are you handling the loss of David?

It’s really sad. A lot of my life is tied up with that guy. He filled in a lot of blanks for me at the beginning. I was really shy, and David will talk to anybody all day. Croz was just a very special human being. He could make you feel just great about everything, and then 10 minutes later say two more words and make you feel [shrinks two fingers together] that big. So, he had this power.

What were some of your experiences with him like outside of the studio? Did you ever go sailing on his boat, the Mayan?

When I went sailing with him was on the Gulf Stream. It was Graham [Nash] that made the big jaunt around through the [Panama] Canal and up to California. I couldn’t see being on a sailboat with those two at the same time for that long [laughs]. I’ve been sailing before and [by] week two it could have been a bit much. And they of course submitted several legends that turned out to be almost true, which I spent a lifetime correcting.

I want to ask you about this new live album, Live at Berkeley 1971. I personally really love the music you were making during this period of your career. You were writing so many songs for your solo album Stephen Stills 2 and then afterwards for Manassas. What was this period of your life like?

Everybody hits a creative spell like that I’ve noticed. Like, [Paul] McCartney wrote three albums at once back in the day. It’s a matter of course, you know? Get a little wind in your sail and you’re feeling good about yourself and everything else is going. It’s got its own dynamic. I pulled back to myself and went up to Colorado and just went on a tear.

Where did the idea come from to include the Memphis Horns on the tour?

My managers, Michael Garcia and Michael John Bowen, suggested the Memphis Horns. I went, “Wow, that’s really a far-out idea!” I had a school band background and learned how to work with an ensemble. It just fit together. And God, what a magnificent bunch of guys to play with! There were old salts in there like [saxophonist] Floyd Newman. He was the boss, really. He and I took to each other like two ducks. When we went to Memphis to rehearse, I used to leave the band and go up into the balcony and listen. [Drummer] Dallas [Taylor] would put them through their paces and it was fabulous.

Tell me about Dallas Taylor. You worked with him on several projects through the years, including the first Crosby, Stills & Nash record. What was it about playing with Dallas that you enjoyed?

He listened and he played the song. We could correct all the rest of it, but the instinctive things? He did all that. We could read each other’s minds and stuff. The things you can’t teach, he already knew. We could work off the groove. And he would let me play his drums and show him.

Oh, see now there’s a thing.

Even Joe Vitale had trouble with that. But the great ones will always recognize another drummer and say, “Oh sure, sit out and show me. Just don’t readjust my drums.” A lot of those Latin pulses and stuff, it’s a feel that I have innately, and it escapes some gringo musicians.

This set really does exemplify a lot of the different flavors that you’ve exhibited throughout your career. Acoustic. Electric. Country. Soul. “Love the One You’re With” is a great opener.

I couldn’t believe how fast “Love the One You’re With” was.

It’s speedy.

Yeah, well, we were excited. It was the opening night.

And then you got David to play on “You Don’t Have To Cry” and “The Lee Shore.”

Well, first of all, he didn’t play on “You Don’t Have To Cry.” He sang. That was me and Steve Fromholz on the two guitars on that. And then he played on “The Lee Shore” because it’s his song. He had the grace to come and see me with my solo act. We were backstage before the show and I said, “We do ‘The Lee Shore.’ Come on and do it with us. You take the lead.’” And we just walked on and did it. We didn’t obsess about it or go on a trip. We just threw down.

That’s amazing. Why did you include “The Lee Shore” in the rotation?

Because I sing it really well.

There you go.

It was easy to step aside and let David take the lead. I’d sing a low part or I’d sing the high part and Steve Fromholz would sing the low part. Steve Fromholz was a great musician. He could really flat pick. He died a few years ago, and it was quite a loss. He was a really great folk singer from Texas that I met in Colorado.

I know you knew Chris Hillman before this time, but is it true that you kind of linked up with him and began kicking around the idea for Manassas during this tour?

Chris Hillman looms large in my legend. He actually wanted to produce the Buffalo Springfield. And he was responsible for us getting at the job at the Whisky [A Go-Go] in the first place.

Wow.

Chris is a standup guy, man. I’m telling you what. He’s been my dear friend for all these years. I owe him a visit.

How did the Manassas band itself coalesce?

Well, Chris and I put it together. [Steel guitarist] Al Perkins was the first bit. And Dallas bought into it. And then we had Joe Lala to keep a Latin influence in and [bassist Calvin] “Fuzzy” [Samuels]. And then [keyboardist] Paul Harris came along. Don’t argue with it. Sounds great. Just everybody play a little less because there were a lot of guys. You can’t overwhelm the singer. And for all the time that we spent on lyric police, if you cover up the lyric with too much of a wall of sound, you’re defeating your purposes.

As the bandleader how do you manage all of that? What do you listen for?

How it fits together. You like jams, but there’s nothing worse than eight guys jamming, because it’s chaos. If you like anarchy, great. But I like a little organization. And then you leave room for the jams.

Obviously, you’re a guitar player first, but you’re also famously known as “Captain Many Hands.” What other instruments do you specialize in?

I play keyboard and bass. I was second in the voting with the Playboy Jazz All Stars one year because of my bass playing. I think Stanley Clarke won that year.

Is there anything new that you’re currently working on?

I’m very relaxed because I’m not putting any stress on myself. COVID left a couple of presents about my wind and stuff like that. I had it twice.

Oh no.

I’m building my strength back up. Knocked me on my ass a couple of times.

I’m sorry to hear that.

It happened. It killed a lot of people.

It did. I got it, too. I didn’t die, so that was good.

Well, there you go. You’re here. Obviously, it didn’t cost you energy either.

I got oodles of that. I’m thinking about climbing Mount St. Helen’s next month. I got big plans, Stephen.

You’ve got that personality buddy. I appreciate your enthusiasm.