In the acute psych wards I’ve been in, there is a kind of paranoia about music – that it’s a dangerous force which could unravel the whole system, make the patients go mad(der), induce an uprising, reduce the hospital grounds to rubble.

Phones can be confiscated; stereos don’t get through the front door. And singing is a sign you’re fucked. Talking softly is normal; bursting into song means you’re in the exact right place doing the exact wrong thing.

But this changes in those psych wards with privileges like carpet, bad art, and metal cutlery. Here music is seen as the opposite. What was denied you when you were suicidal is now compulsory. You are not only allowed music; you are obliged to both listen to and generate it.

For a musician, this only looks like a blessing. I once knew a once-pro jazz pianist who’d shifted mid-career to become a high-school English teacher. I asked him why he wasn’t teaching music at the high school instead. His four-word answer: too many bad notes. And maybe, you know, there is something about the danger of music, like caffeine and needles and rusty blades: something that the acute psych wards recognize.

—

I meet J in a lunch line. He is one of those men – a mental hospital type, even – who comes across either as a sweet overgrown boy, awkward and deferential, or someone who might knife you, right here, right now.

J is, according to all innuendo, an expert in violence. I’ve been in group with him where he recounts how he’d lost an incisor in someone’s cheek, how the tooth became embedded in a foe’s face as the result of a bite, but that the loss has less to do with the depth of the bite or the “aggro of the attack” but the poor condition of J’s gums, “receding gums because of chronic periodontal disease process,” he clarifies with a ventriloquist’s polish.

The next time I see him is in a “drum workshop.” He wears a sweat-soaked Appetite for Destruction t-shirt which sticks to his body like a fat coat of wet paint. The therapist has us sit around her in a circle, and then she hands ‘round a djembe for each of us to tap out a beat representing how we feel this morning.

The first girl smiles and then pulls out a rip-off of the start of Queen’s ‘We Will Rock You.’ That feels like cheating to me. The young guy next to her takes the drum and delivers an extraordinarily complex and a-rhythmic spray of nonsense that would be equally at home in free jazz and a toddler’s room. He passes J the drum.

J sits with the drum for a moment, and then retracts his right hand in a about-to-smack-a-child-on-the-ass position. And then relaxes it to the floor. J takes a deep breath, raises his hand again as if to start, and holds it there for a moment – before dropping it again, turning to the therapist and saying: “I don’t know what I’m supposed to do.”

“Just tap out a beat to express how you’re feeling.”

“I don’t know how to do that.”

“Just do your best.”

J raises his hand a third time. Pauses. Then hits the drum like it’s an enemy. Once. J draws his hand back again. I’m scared that this time his hand will split the skin. But he just throws the drum down and stands. “This is fucking gay,” he says. “You can all get fucked.”

He storms out, slamming the door.

There’s a moment’s silence. The therapist looks at us. “Can we just check in and see how everyone is feeling?”

Another short silence.

“Can I do a new beat?” a goth girl says.

—

Music is its own thing, not just because of where it comes from – wherever the hell that is – but where it has to land. Hearing isn’t like the other senses. You can always shut your eyes if you don’t want to see something. But, unlike some freak lifeforms (like hippos, otters, and seals) humans can’t shut their ears. It’s like not having extendable eyeballs (I’m looking enviously at you, snails). It’s a liability.

I learn this in other mental hospitals, where patients are more like hotel guests, able to bring in not just personal stereos, but goddamn instruments. (I could write a Lonely Planet Guide to Mental Hospitals, if anyone from that venerable publisher is reading this.) One girl plays Fleetwood Mac’s (so-called) White Album from 1975 like it is an ancient tongue she’s trying to decode – day and night. And slowly her focus draws down, becomes granular, microscopic. Over the course of a few days, she goes from the full album to just a few songs: ‘Monday Morning’, ‘Rhiannon’, and ‘Landslide’ – and eventually just ‘Landslide‘, which she plays day and night on a hateful loop.

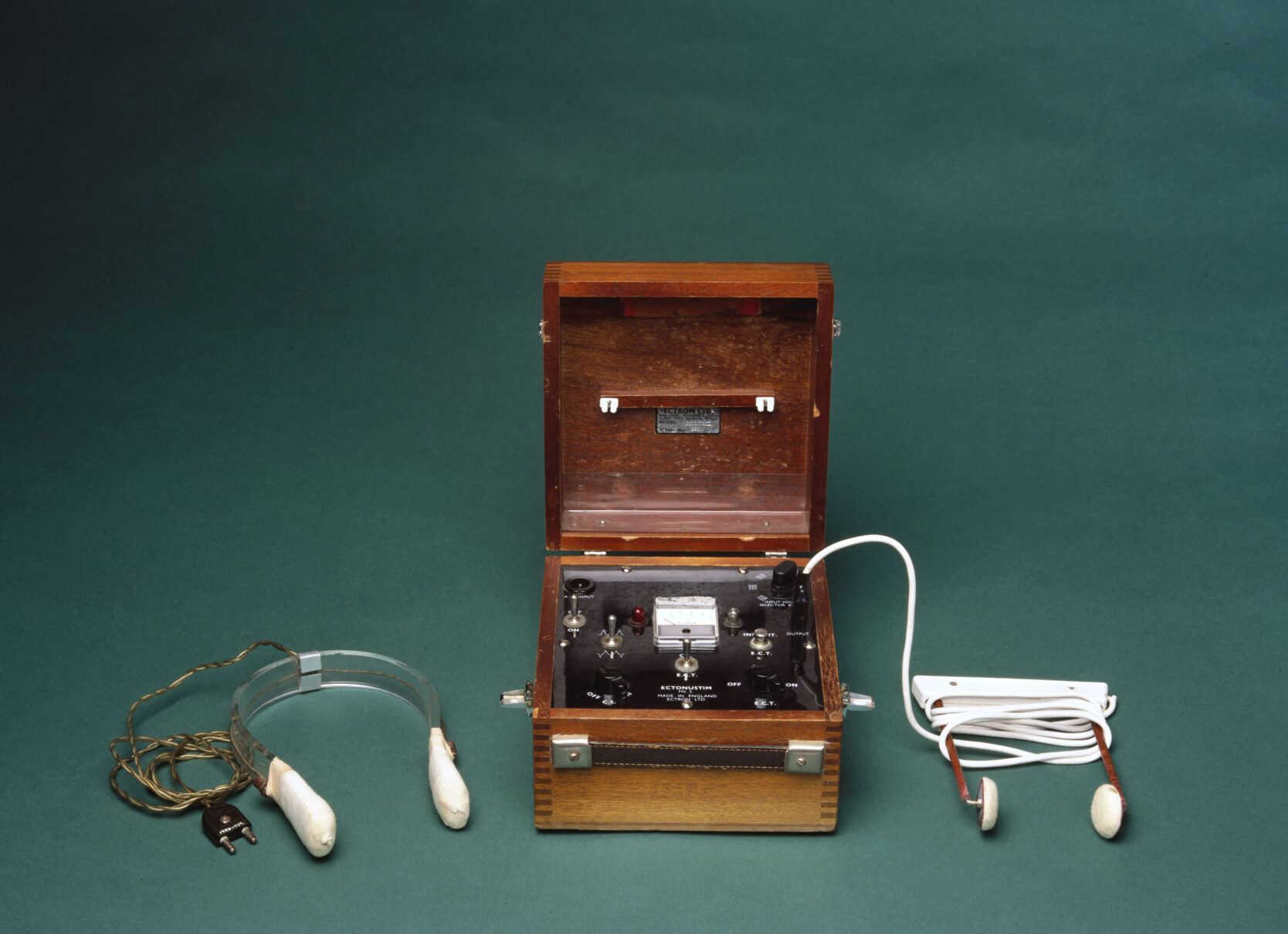

I wouldn’t have dealt with it well at any point, but I am in that hospital getting ECT, and shock treatment messes with my hearing. Sometimes things sound like they’ve been stripped of all treble, like a stereo in a closed-up car; and sometimes the distance collapses between my head and whatever is making a noise, like the world suddenly puts headphones on me to play me its bad demos.

So Stevie Nicks is nowhere and suddenly she sings directly into my head like I am her microphone – and then she does it again. It wears down my teeth, makes me retch. The pit comes when a new patient, walking past the Fleetwood Mac war room, overhears it and knocks on the door. “Oh my god I love that song. Can I borrow the CD?” I didn’t want the CD. I wanted guns, knives, hand-grenades.

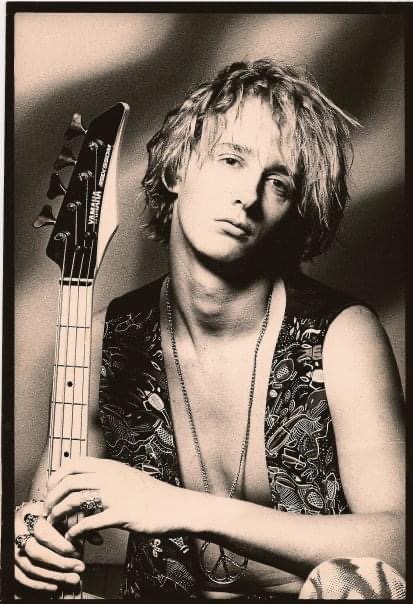

This was torture – albeit unintentional. But we know music is used deliberately to this end. On Christmas Day, 1989, the Panamanian autocrat Manuel Noriega sought asylum in the Vatican’s embassy in Panama City after the US incursion. American troops surrounded the building, but Noriega wouldn’t budge. In response, a fleet of speaker-laden Humvees arrived and proceeded to assault the fugitive with a playlist engineered with exquisite cruelty: Twisted Sister, Billy Idol, Bon Jovi, New Kids on the Block, Def Leppard. A bit over a week later, predictably, Noriega surrendered. Who wouldn’t?

The US military has since repeated the strategy, assaulting David Koresh’s Branch Davidians with Nancy Sinatra and Tibetan chants, the Taliban with 90s metal. Most terrifying of all though was perhaps the deployment of Barney the purple singing dinosaur against uncooperative captives in Iraq, who were forced to listen to his ‘I Love You,’ whose chilling opening verse runs:

I love you, you love me.

We’re a happy family.

With a great big hug,

And a kiss from me to you,

Won’t you say you love me, too?

Amnesty International responded by suggesting that such tactics contravened the Geneva Convention and could be considered “torture”. The sane are obviously with Amnesty International.

The power of music, of sound more generally, allows it to seep right past those front parts of the brain and tap into something more reptilian, over which reason has no jurisdiction. This is why we can come to blows with neighbors over it, why we might break up with someone for their snoring, weird breathing, sighing, or their Spotify playlist crimes. And time can wreak havoc on even these cruel adjudications.

When I was floor-bound, coming off junk (the first time) I listened to Sigur Ros’s second album on repeat. There was something in it that soothed me at the same time that its melancholy didn’t seem like some denial that I was flat on my back, sweating, joints on fire. I still think the music is jaw-dropping, but that album is now poison to me. It’s a nervous system time machine and there’s no fucking way I’m going back there. The acute psych wards at least get that right.