You don’t have to read far in the biographies of Little Richard, Sam Cooke, Aretha Franklin, Wilson Pickett, and Otis Redding to discover that they grew up singing in one church or another. In fact, practically every classic-era soul or R&B singer either first lifted his or her voice in sanctified settings, or was directly influenced by those who did.

Unfortunately, such origin stories can give the impression that African-American churches were a farm system whose only purpose was to supply the “big leagues” with marquee talent.

A more accurate baseball metaphor would be the pre-Jackie Robinson Negro leagues. Like the action taking place on those segregated diamonds, the sacred “action” taking place in or emerging from the musical quarter of the black Christian community could easily hold its own with the action taking place on secular playing fields.

You’ll sometimes hear it said that the original gospel singers — slaves in the American South — used their songs as code for secretly expressing feelings, thoughts, and aspirations that would have otherwise gotten them whipped or worse, that the songs’ messages of Christian hope meant little if anything to them, coming as they had from the same white men and women who were holding them in bondage and treating them like beasts.

Maybe.

But even now, when the ancestors of those slaves have no need of code, gospel music thrives. Anyone who listens to it and comes away thinking that its references to God, Jesus, and Heaven really mean something else (government? George Floyd? the NAACP?) is in serious denial.

Choosing the 10 best gospel albums of all time is tough. Many of the genre’s seminal recordings were made before the “album” concept solidified, taking instead the form of 78s, 45s, or other discrete formats. So it is that the following list excludes performers best represented by box sets of three discs or more.

The resplendent Mahalia Jackson, for instance (see The Apollo Sessions: 1946-1954 on Westside), did more than anyone else to hip white audiences to what they’d been missing, and the unconventional stylings of the guitar-wielding Sister Rosetta Tharpe (see The Original Soul Sister on Proper) have gotten her into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame (ahead of the New York Dolls and the MC5, for what that’s worth). But neither woman in her prime made or even tried to make a great 30-to-40-minute collection of mutually reinforcing songs that would stand alone as an artistic “statement.” And the first 37 years (1871-1908) of the world’s first official gospel group, the Fisk Jubilee Singers, went undocumented in sound altogether.

But if choosing the 10 best gospel albums is hard, identifying 10 great gospel albums is easy, because they abound. They work as artistic statements and as statements of belief.

So we’ll call these the best, and they are great. Their peaks are emotionally overwhelming. Whatever (or Whoever) it is that they have, you’ll want it too.

And if you’re not careful, you’ll get it.

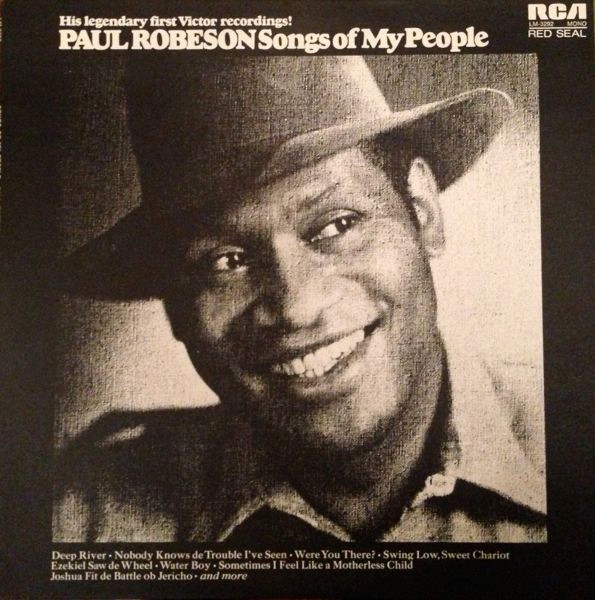

Paul Robeson: Songs of My People (RCA, 1972, rec. 1925-29)

Paul Robeson excelled at sports, stage, and screen. (He practiced law awhile too.) A preacher’s son, he also achieved fame as a performer of the slave songs known as “Negro spirituals.” These renditions of “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot,” “Nobody Knows de Trouble I’ve Seen,” “Joshua Fit the Battle ob Jericho,” “Ezekiel Saw De Wheel,” et al. — recorded by Robeson and the classically trained pianist Lawrence Brown for the Victor Talking Machine Company during the Roaring ‘20s — were more redolent of Carnegie Hall than of plantations. But Robeson was selling in, not out. Like the Motowners who decades later would imbue the “Sound of Young America” with class and soul, Robeson considered the sublimation of intense emotion to his day’s standards of artistic decorum to be a step up, up, and away from an excruciating past that for African-Americans of his generation was never far from becoming all too present.

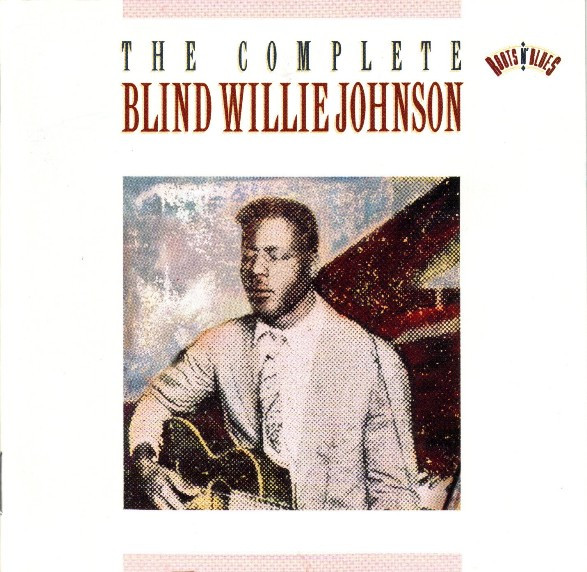

Blind Willie Johnson: The Complete Blind Willie Johnson (Columbia/Legacy, 1993, rec. 1927-30)

Blinded at seven and dead before 50, Blind Willie Johnson lived the quintessentially hard life of a street-singing gospel-bluesman. Except for “When the War Was On” (a mini-history of World War I), this comprehensive two-disc set reflects the rich tradition of spirituals, hymns, and revival songs unique to the South in general and to Johnson’s native Texas in particular — none of which would matter if Johnson’s singular style hadn’t transformed them from items of historical interest into living testaments of faith. Over his eloquently lyrical slide guitar, he sang in a barbed-wire-on-gravel growl that brooked neither sentimentality nor pretense and that lifted “God Don’t Never Change,” “Dark Was the Night, Cold Was the Ground,” “It’s Nobody’s Fault but Mine,” and “Lord I Can’t Just Keep from Crying” into the ranks of the most powerful acoustic music, gospel or otherwise, ever recorded.

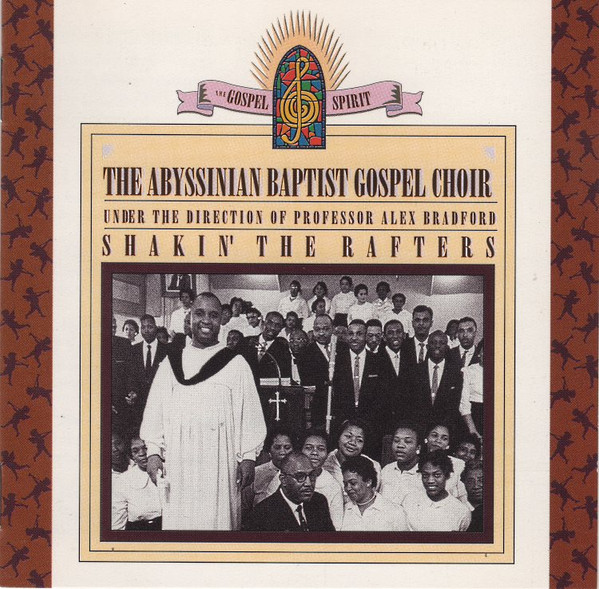

The Abyssinian Baptist Gospel Choir Under the Direction of Professor Alex Bradford: Shakin’ the Rafters (Columbia, 1960)

If “Said I Wasn’t Gonna Tell Nobody” had been the only number that Columbia’s engineers captured when they set up mics in Newark’s Abyssinian Baptist Church over 60 years ago, the effort would have been worth it. Beginning with Alex Bradford’s signature piano riff, the song charges into a rollicking, organ-enhanced boogie-woogie that for five-and-a-half minutes undergirds an almost comically ecstatic call and response between Calvin White (who’s coming unglued with joy) and the choir (whose 100-plus voices could easily be a thousand). That none of the other 11 songs come as close to shakin’ the rafters is probably just as well. No need to get your church shut down over something as mundane as the building code.

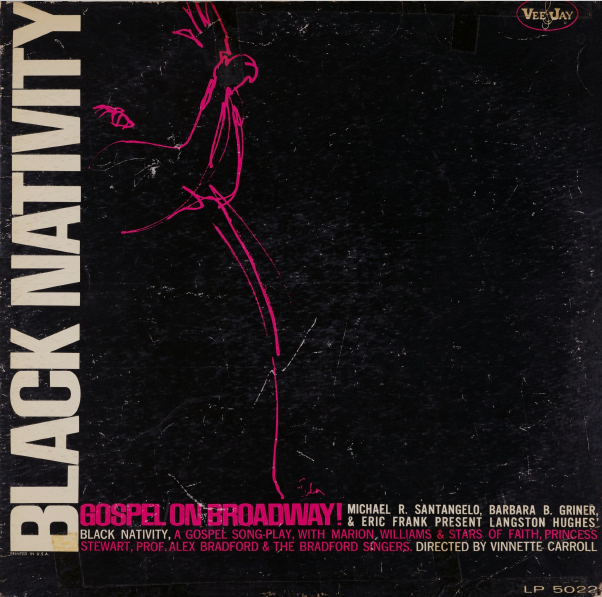

Black Nativity: Gospel on Broadway! (Vee Jay, 1962)

That Langston Hughes conceived this 1961 “Christmas-song musical” made it seem like the final flowering of the Harlem Renaissance. That it became an off-Broadway hit made it seem like the first flowering of gospel’s finally having arrived. “For cultivated musical ears,” wrote the New York Times’ Howard Taubman, “a little gospel singing might go a long way, but how these singers can belt out a religious tune!” (For the time — and for the Times — that was high praise.) Credited to Marion Williams and the Stars of Faith, Princess Stewart, and Professor Alex Bradford and the Bradford Singers, the carols and the spirituals intersect like the meeting of Africa and Europe that they were, their bond fused by a revival-worthy piano and organ. As for telling the female soloists apart, Stewart is the molasses-voiced alto, and Williams, who even at her most powerful seems to be reining herself in a little lest she uncork more than the audience can handle, has the brighter, more flexible voice. Whether you award the women the victory on points or frame their achievement as a knockout, their one-two punch could really deck the halls.

Clarence Fountain: In the Gospel Light (Jewel, 1970)

A founding member of the Five Blind Boys of Alabama and their best-known lead singer, Clarence Fountain launched his six-album (give or take) solo career with these exuberant sessions. And, frankly, he sounded thrilled to be on his own, punctuating the uptempo numbers with mighty shrieks, wringing every drop of sentiment from the slow ones, and beginning “It’s Done Got Late” with this entirely believable sermonette: “I was standin’ in the record studio the other day. A man walked up to me and said, ‘Son, you see, I be-lieve that you have a nice voice. But I tell you what you oughta do, you oughta go out in the world and sing some rock ‘n roll and make you a pocketful of money. But I told him, I said, ‘I don’t mind singin’ rock ‘n roll, but you’ve gotta sing the way I wanna sing. You’ve got to rock for Jesus, and roll for God!” Talk about putting the “cross” in “crossover.”

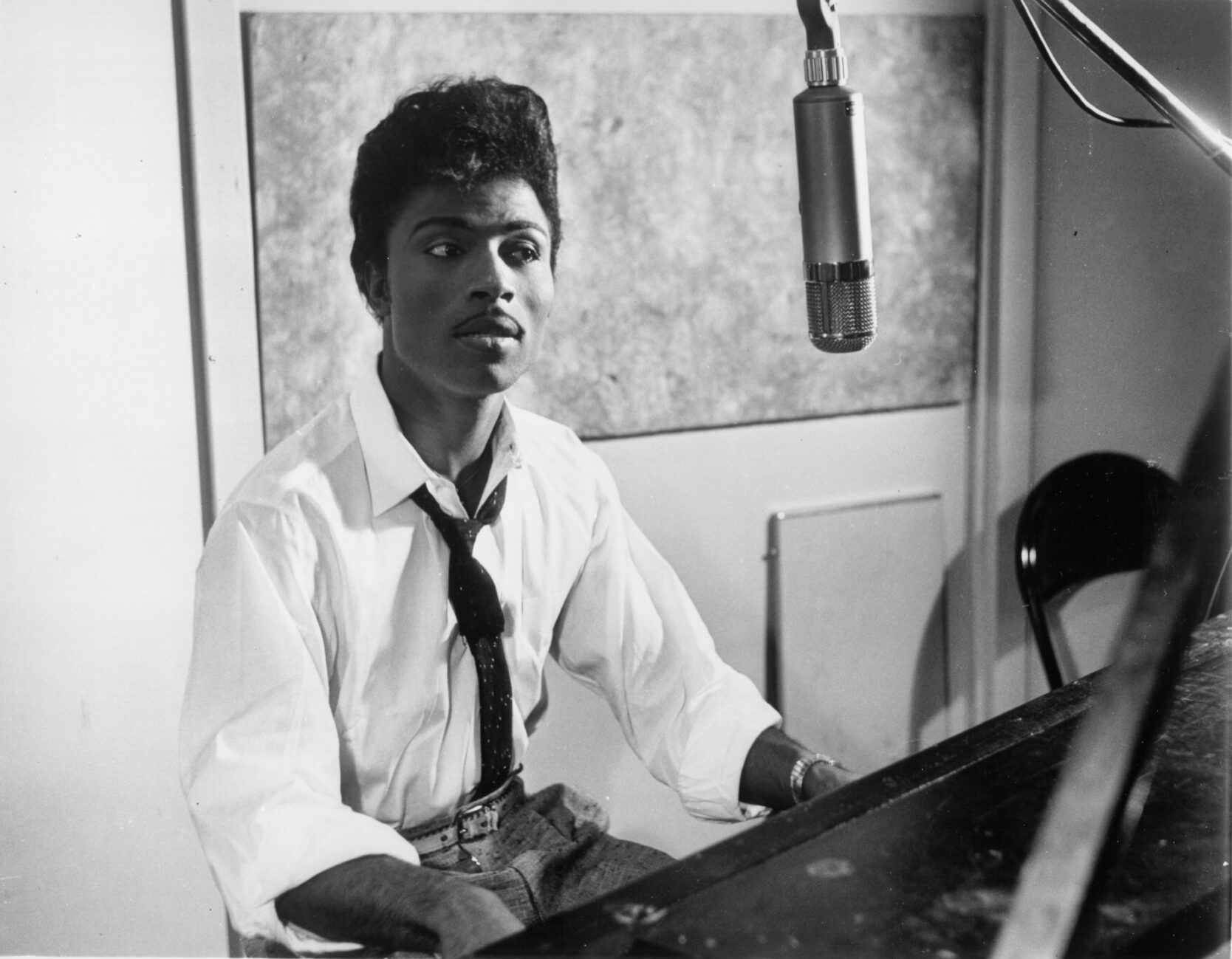

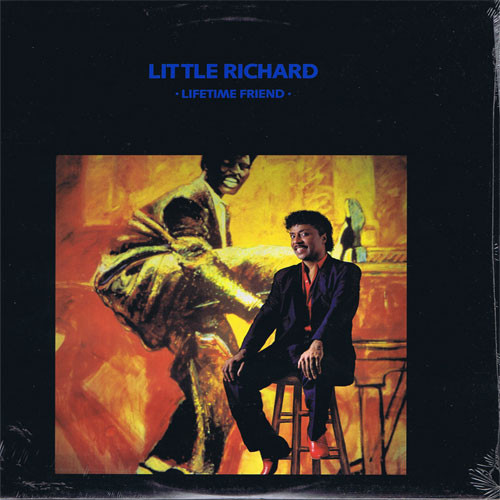

Little Richard: Lifetime Friend (Warner Bros., 1986)

Lifetime Friend was Little Richard’s last official long player (unless you count his children’s disc for Disney and his re-recorded-hits disc with Masayoshi Takanaka), and it should’ve been a hit. The romping, stomping “Great Gosh A’Mighty” doubled as the lead single from the Down and Out in Beverly Hills soundtrack and rotated heavily on MTV. But it missed the top 40, and the album stiffed. As a gospel LP in rock ‘n roll clothes, it accrued little mainstream cachét. Barely mentioning God and never mentioning Jesus (the producer Stuart Colman had a pronouns-only policy), it was no shoo-in at gospel radio either. Still, Richard and his mostly uncredited band (Travis Wammack played guitar and wrote or co-wrote four tracks) threw themselves into the proceedings, creating the antithesis of the Mahalia Jackson-like deep-soul gospel sides that Richard had cut circa 1960, the first time that he tried leaving everything behind to follow Christ.

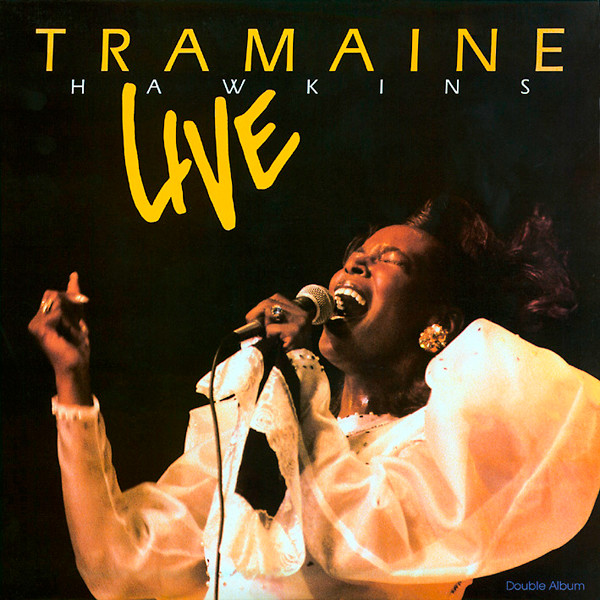

Tramaine Hawkins: Live (Sparrow, 1990)

There’s plenty to rave about: Hawkins’ diva-worthy pipes and the way that she keeps them under control until she can’t, the guest turns of Jimmy McGriff and Carlos Santana that light a fire under “Lift Me Up,” the medley of songs by Hawkins’ then-husband Walter that at 25 minutes never seems too long. But what’s most rave-worthy about this soundtrack to a live-in-Oakland TV special that can nowadays only be seen as a VHS rip on YouTube is the explosive performance of Calvin B. Rhone’s “Praise the Name of Jesus.” The song detonates and detonates. And just when you think that neither Hawkins nor the choir could detonate again, they modulate upward and do just that. The album version fades out at 7:28, the TV version at 8:45. If the complete take ever surfaces, get thee to a fall-out shelter.

West Angeles Church Of God In Christ Angelic Choir: Little Saints in Praise (Sparrow, 1990)

By 1990, splashy synthesizers and an increasingly glitzy sheen were becoming common in gospel, boosting the music’s commercial appeal (theoretically) but distancing it from the earthiness that had made and kept it vital. For this children’s choir, though, the approach worked. Perhaps it was a case of two kinds of cute canceling each other out, which is as good an explanation as any for why the de-Bono-fied “Pride (In the Name of Love)” never gets old. But it’s on the high-energy medleys, especially the one comprising “Kum Ba Yah,” “Sweet Jesus,” Joy Bells,” and “Yes, Lord” that these kids really say it loud: They’re believers, and they’re proud.

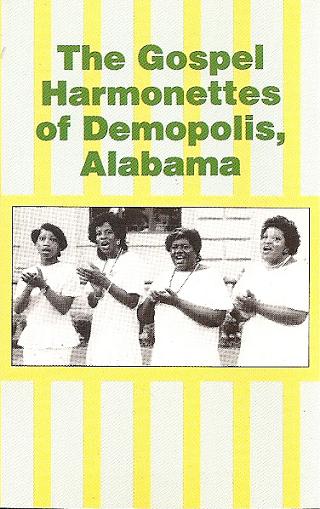

The Gospel Harmonettes of Demopolis, Alabama: The Gospel Harmonettes of Demopolis, Alabama (Global Village, 1992)

These four a cappella-singing Alabama women had just begun performing outside their home county of Marengo when this cassette appeared, and even then their clothing-factory day jobs restricted their 100 or so annual performances to the immediate Southeast. Named after Dorothy Love Coates and the Original Gospel Harmonettes, the quartet honors its namesakes with bright, solid harmonies that build and build. But in lieu of instrumentation and dominant lead singing, they rock the rhythms harder than their Birmingham forebears, striking a balance somewhere between Africa and the Jordanaires and nailing uptempo riffs that ring in your head long after they end.

Kirk Franklin and the Family: Kirk Franklin and the Family (Gospo Centric, 1993)

Kirk Franklin didn’t realize it at the time, but when he debuted with this live-in-Fort-Worth game changer, the giant on whose shoulders he was standing was Andraé Crouch, the gospel performer who did more than anyone else to blend black and white Christian-music audiences in the ’70s. Like Crouch, Franklin shared lead vocals with members of his extended “Family” (Crouch’s was called “the Disciples”) and preferred hymn-like, quiet-storm chord changes to those rooted in the blues. Unlike Crouch, who, though his choir ended up enriching Madonna’s “Like a Prayer” and Michael Jackson’s “Man in the Mirror,” never crossed over himself, Franklin went platinum his first time out. And lest anyone think that he might’ve just been using gospel as a stepping stone to secular glory (he’d top Billboard’s Hot R&B/Hip-Hop chart with the Funkadelic-sampling “Stomp” in 1997), he led with “Why We Sing,” in which he embedded the following couplet: “If somebody asks you, ‘Was it just a show?’ / Lift your hands and be a witness / and tell the whole world ‘No.’”