Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.

The First Amendment, adopted December 15, 1791

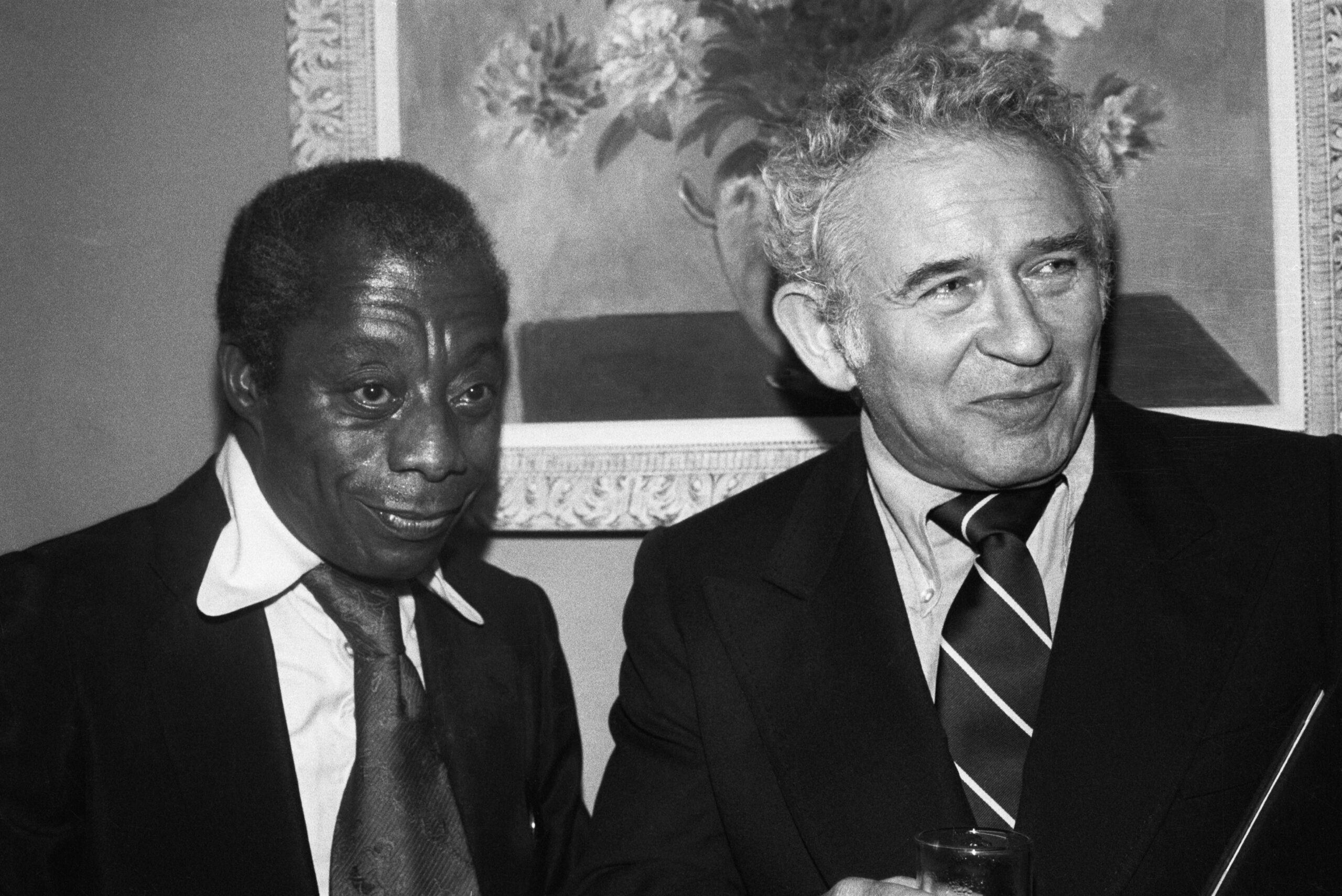

It almost feels like an opium dream to think that rich-born white conservative William F. Buckley Jr. and queer, Black struggling writer James Baldwin could debate each other in highly charged matters of race at a university of the Western world without the event being drowned out or torn up by legions of the righteous — if it was even permitted to be held in the first place.

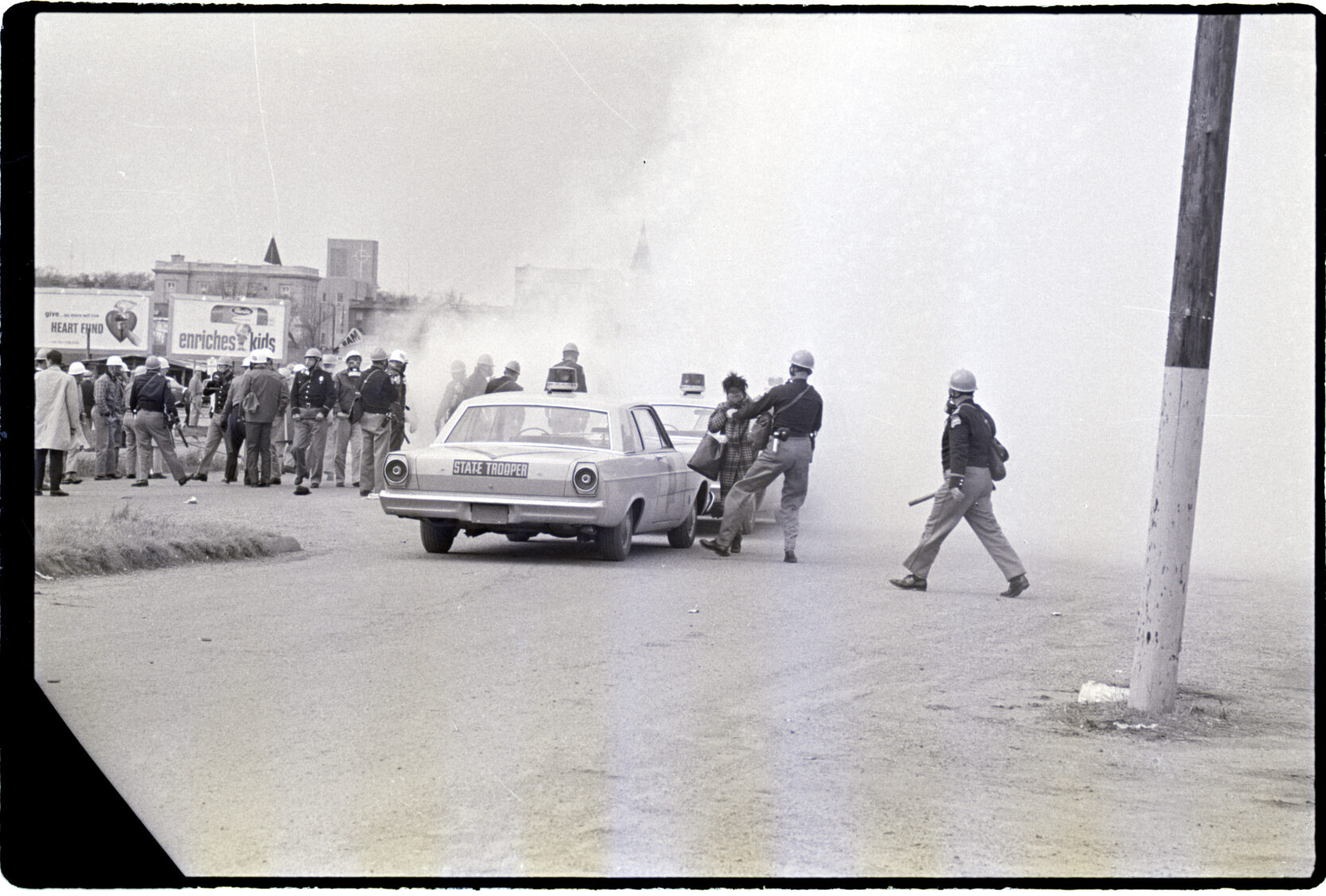

Yet debate they did on the topic of “The American Dream is at the Expense of the American Negro” at the University of Cambridge in 1965.

It took place without fist fights and smashed windows. Without pepper spray and torn up seating. Without pipe bombs or placard battles.

It was a contest of opposing spoken, structured arguments. Pressing the case for the affirmative, Baldwin was overwhelmingly voted the winner.

Neither debater then needed a phalanx of cops to rush them out a back exit clear of furious mobs.

Impossible to imagine anything like this happening today, even if debate and the safe exercise of free speech are at the very heart of the democratic process. For even in relatively free and open societies, free speech has no shortage of enemies.

To explore the state of play, SPIN IMPACT speaks here to Nico Perrino, Executive Vice President of the Foundation of Individual Rights and Expression (FIRE), an organization that fights censorship and defends the First Amendment rights of all Americans.

SPIN: Do you agree with Noam Chomsky’s statement: “If we don’t believe in freedom of expression for people we despise, we don’t believe in it at all”?

Nico Perrino: Yes. If we only care about preserving free speech for those we agree with, free speech ceases to become a value, and instead becomes a hobby.

How do you define free speech?

Free speech is the ability to be who we are and speak our minds. It’s essential for the democratic process, peace, creative and artistic expression, innovation, and prosperity. In order for free speech to thrive, it must be protected not only by the law, but also by cultural norms that encourage its exercise.

Why is free speech fundamental to democracy?

Sigmund Freud once said that civilization started the day that man cast a word instead of a stone. And what is democracy, if not the use of our words instead of violence to solve our problems?

We debate, we discuss things, and then we come to some sort of resolution — to our conclusion about how we’re going to live in a free society.

There really are only two ways to solve our disputes: words or violence. And democracy is the use of words.

To the extent you limit conversations in a democracy, you’re limiting people’s ability to participate in the democratic process.

Now, are there going to be people who have boneheaded, repugnant, even bigoted ideas? Yes. But we solve that problem by speaking to each other.

The moment that we give up on the idea that words can change people’s minds, that words can breed compromise, is the moment we give up on the idea of democracy.

All we are left with is force to compel belief. And that’s a very facile belief.

When you censor people, you don’t change their minds — you just don’t know what they actually believe.

Which specific people and organizations in America are doing the most to undermine the First Amendment, and what are they doing?

The government is always the greatest threat to free speech. Totalitarian governments understand that in order to maintain control they must punish dissent.

New ideas are a threat to the status quo, and defenders of the status quo throughout history have always looked to censorship to preserve the current order of things.

For much of the 20th century, free speech was the darling of the political left as social justice activists utilized it to advance their causes.

Recently, particularly on college campuses, it has been of growing interest to the political right as conservatives see their voices muzzled in academia.

In America, colleges and universities have long been a battlefield for free expression. Colleges are our marketplaces of ideas, where knowledge is created, shared, and preserved. Restrictions on speech in such an environment are particularly insidious and concerning.

Where does FIRE stand on the “deplatforming” of people making statements via social media that are deemed false and/or grossly offensive to many others? This, of course, would include President Donald Trump re: the 2020 election, and Ye/Kanye West spruiking anti-Semitic comments and material.

In general, we think it’s valuable to know what people actually think. As the writer Jonathan Rauch once said, censorship is like breaking the thermometer: You may no longer know the temperature, but that doesn’t mean it’s no longer hot outside.

We should meet speech we disagree with, with more speech, not with censorship.

Are restrictions against hate speech inconsistent with the First Amendment?

Yes.

The Supreme Court has never carved out a “hate speech” exception to the First Amendment. Nor should they. Hate speech is a subjective phrase: What’s hateful to you may not be hateful to me, and vice versa. The phrase then ends up getting used by those in power to punish dissenting viewpoints.

A clear, unambiguous answer on a controversial topic? I’m not used to that.

At FIRE we are unapologetic in our defense of free speech, because we see it as a foundational human right that is essential for human progress, creativity, innovation, democracy, and peace. We don’t mince words in defending it.

Too often the defense of free speech comes with a lot of throat clearing and genuflecting before other values, before the actual defense of free speech comes out.

That doesn’t mean that the right doesn’t come with complications or consequences, but we think that on the whole it’s better to defend it than to not.

What are your thoughts on Elon Musk? After presenting himself as a champion of free speech, since buying Twitter he seems to be thrashing about.

Elon Musk is a man for whom I had a lot of hope. I mean, Twitter in the past has censored far more than it should have. It removed journalism about Hunter Biden’s laptop that it tagged essentially as misinformation but ended up actually being true.

That’s one of the problems with the “misinformation” category in general: It’s used to censor.

They took off conservatives who expressed conservative viewpoints about gender ideology. They removed a satirical conservative publication, kind of like the Onion, called the Babylon Bee. They often did this with little transparency and utilizing speech codes that were vague, overly broad, and it was not easy to know what offended them.

Enter Elon Musk. He says that free speech is important for the future of civilization: check. He says free speech is important for understanding the world as it is: check.

Then he takes over Twitter, and very shortly and without notice starts implementing new speech codes. Very little transparency. He suspends the accounts of critical journalists. He suspends those who share links to competing platforms. Things that offend the ethos of the modern open internet.

And he often does this through polling Twitter users, which, when freedom of expression is something that should not be up to a majority vote, is troubling.

I’ve been discouraged by his recent actions. And, more broadly, as people see that some of the most vocal advocates for free expression are themselves hypocrites on free expression, it’s tarnishing for the brand, and it makes the work that we do at FIRE more difficult.

But Elon Musk is now the man with power, and he’s suffering from the curse of power, which is censorship.

It looks like a shiny tool when you have it in your hands and have the option to use it.

Social media is the hot space right now. There’s a lot of efforts to regulate it, often with deleterious consequences for freedom of speech. This is what happens when new technologies come into being. They bring in new challenges, and often legislators seek to use the bluntest instrument possible to address those challenges. And that is censorship, and that can’t be counted as constitutional.

When are restrictions against free speech appropriate or defensible?

First Amendment jurisprudence is the longest sustained meditation on how to have free speech in a free society, and it has generally done a pretty good job of carving out reasonable exceptions to free speech, such as incitement to imminent lawless action, true threats, fraud and perjury, defamation, and speech integral to criminal conduct.

But some of the exceptions are dead letters. They haven’t been given teeth in recent years, and they’ve never quite been overturned, but for all intents and purposes they’re dead letters.

Take the concept of “fighting words,” for example, whereby through their very utterance they can supposedly animate people to anger and violence.

In the free-speech world, there’s this principle that we shouldn’t deprive people of agency. So, the idea that I can say a word that deprives you of your agency and throws you into a fit that results in you committing violence is not what we should expect of a society in which we privilege personal responsibility and individual freedom.

Another dead letter is obscenity: the idea that something has no intrinsic artistic or literary value and so offends the standards of common decency that it should be censored. It’s an exception that’s very rarely seen these days.

How has support for free speech changed over time?

FIRE President and CEO Greg Lukianoff calls free speech “the eternally radical idea” because it is always under threat.

The arguments for it need to be made with every generation, because it’s not something that comes intuitively to us: “Let’s let the people we disagree with speak.” We’re not evolutionarily designed to allow for that. We’re tribal creatures who seek to expel discomfort, and free speech is discomfort.

Poll results are always a mixed bag. People get asked: “Does the First Amendment protect hate speech?” And many of them [incorrectly] think it doesn’t.

Then you ask them, “Should the 1st Amendment protect hate speech?” And many say it shouldn’t. It’s about 50-50.

And then you ask them, “What does ‘hate speech’ mean?” Turns out it means different things to different folks. That’s part of the reason why the Supreme Courts never outlined a definition.

I want to mention the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU). Even growing up in Australia, I saw coverage of it defending the First Amendment rights of neo-Nazis and the Ku Klux Klan. But with all the free speech dramas these days, I just don’t see the ACLU on the scene. So I did some reading and saw some of the old guard — former Executive Director Ira Glasser and longtime ACLU lawyer David Goldberger — publicly saying that the ACLU seems to be deprioritizing the fight for free speech. Do you see FIRE as picking up the baton from the ACLU?

Yes. And Ira Glasser is a mentor of mine. I made a documentary about his life: Mighty Ira. He is a member of FIRE’s advisory council, and David Goldberger is a FIRE legal-council member. A lot of the old-school ACLU folks are working with us these days. I grew up revering those old-school civil libertarians.

Norman Siegel [former Executive Director of the New York Civil Liberties Union] said that if he had a tattoo, it would be the phrase “neutral principles” across his chest. This is the idea of equality under the law; the same rights that benefit our enemies also benefit us.

And that’s the principle that they upheld. But they uphold it at a time when you saw free speech being used as a tool for civil rights activists, gay rights activists, suffragettes, and they understood the costs of cutting down those rights to go after neo-Nazis in Skokie [Illinois]. Or, the Klan in the South.

I fear that my generation in particular is forgetting those same lessons that the older generations learned and that motivated their defense of free speech rights. That’s why I made that movie, Mighty Ira: to remind my generation why these principles are important, and of the costs that come with not having them because we’re pursuing political expediency instead.

The ACLU’s first annual report was called “The Fight for Free Speech.” The second annual report was called “A Year of the Fight for Free Speech.”

Right now the ACLU has 19 different issue areas, of which free speech is one.

Sometimes those issues are in tension, and it’s more difficult to navigate 19 different areas than it is to navigate one.

If you look at Michael Powell’s New York Times profile of [free speech tensions within] the ACLU, Ben Wizner, their foremost free speech lawyer, says FIRE only has one issue — free speech — while the ACLU has many more, and so it’s easier for them [FIRE] to do this work.

I don’t work at the ACLU, so I can’t speak to those challenges. All I can say is the thing that motivates a lot of the work we do at FIRE today is the same thing that motivated many of my heroes, like David Goldberger, like Ira Glasser, to defend free speech in the most hostile environments.

If you watch my documentary [Mighty Ira], you’ll see David Goldberger sitting there on the Phil Donahue Show in 1978, surrounded by Holocaust survivors, a Jewish man himself, making the argument why neo-Nazis should be allowed to rally in the town [Skokie] where these Holocaust survivors live.

God.

Talk about earning your third-degree black belt in free speech advocacy.

Now the ACLU and its position at Skokie is revered, but in 1978 it was reviled. So, there is something to be said for standing on principle, waiting for cooler heads to prevail, and making the arguments to bring people around to these fundamental values.

That’s why we’re pursuing our advocacy. We try to stay focused on the principle when everyone else is calling for censorship. We understand that in the long run censorship has always been a losing play.

We don’t look back on the efforts to ban comic books or censor the radio or censor the printing press as worthwhile endeavors. In fact, we look back at them silly — futile — but the people who were advocating for that censorship thought of the free speech taking place in those forms as just as dangerous as how people today look at speech happening on social media, for example.

The censor never wins in the long run.

By holding firm on free speech, does FIRE finds itself positioned differently over time in the political spectrum, with a changing cast of allies and enemies?

Oh, yeah.

One day last year we were defending pro-life students at the University of North Carolina who were going to have their funding for campus events revoked, and the next day we were defending pro-choice advocates in South Carolina, where that state legislature was looking at passing a law banning speech about abortion.

One day we’re defending a Jewish student group on campus. And the next we’re defending the Students for Justice in Palestine group on campus.

Or one day we’re defending a Turning Point USA group that’s being denied the right to be a recognized student group on campus because people find their MAGA viewpoints offensive. And then the next day at Georgetown we’re defending the Bernie Sanders group on campus that has been told they can’t become a registered student organization and advocate for political beliefs.

We get accused of being conservative because we’ll defend the right of a student group to invite Gavin McInnes, founder of the Proud Boys, to speak at Penn State. But the next minute we’re criticizing Elon Musk for passing speech codes at Twitter and banning journalists that are critical of him — after him saying that he’s a free speech absolutist.

That’s one thing that you learn in doing this work. You’ve always got to expect to defend speech on opposite sides of any issue. So in some areas people will see you as conservative, and in other areas they’ll have the opposite view.

It’s really tough to find principal donors who are going to stick with you after you go after their side. So we have a goal to create a free speech army: a group of principal free speech advocates who are not going to abandon the cause as soon as their side has the power to censor.

We lose donors all the time because they get annoyed by things that we’re doing, but at the same time we bring new donors in. For the past 10 years, we’ve grown considerably. When I started at FIRE in 2012, we were 15 staffers with a budget of $2 million a year. Now we are 100 staffers and have a budget of $18 million.

Part of that came from the growing profile of the issue that we focused on exclusively for 23 years: campus civil liberties, with our bread and butter being free expression. That issue rose in prominence over the last decade. As a result, funding to support our organization increased and we were encouraged to expand our mission beyond campus.

We found broad support for a principled, unapologetic defender of free expression in America which can become that tent pole organization that others can rally around when not just legal free-speech rights are threatened, but also the cultural values that support those legal rights.

These include the ability to talk across lines of difference, to play devil’s advocate, and to support the sort of idioms that define many people’s American childhoods:

Sticks and stones may break my bones, but words will never harm me

It’s a free country

To each their own

These aren’t idioms that you hear as often anymore, because the culture for free expression is waning in a way that we need to reverse.

I think of the pushback against free speech by people critiquing what they see as institutional racism and deep social inequalities of power. This is the argument that free speech favors those with the biggest platform and most cultural capital. Is that one of the bigger arguments against free speech? That it’s not free given power relationships?

Yes. It’s one of the bigger arguments.

It’s also one of the most bogus arguments that’s made against freedom of expression.

And here’s why: In a democracy you have the vote that protects the majoritarian rule. The Bill of Rights, with its protections for freedom of expression, then defend against majorities exercising their political power to shut you up.

Freedom of speech is always the tool for the powerless. If you don’t have power, all you have is your voice.

So if you are pushing for censorship, you are tacitly acknowledging that you have power. Or you’re just pursuing a tactic that’s going to be used against you once that power is given to authority.

On college campuses, why would you want to give an administration the power to determine what speech can be heard?

The 1964 Free Speech Movement at Berkeley was a movement to take that power away from the administration, because it was being used to censor civil-rights activists and anti-war protestors.

So sure, give away more power to those in authority and see how well that works out, because history hasn’t demonstrated that it ever works out. Give the power to Barack Obama today. Well, Donald Trump’s going to be in office tomorrow. And how do you think it’s going to be exercised? And I always ask people, when I give speeches on campus, who would you have decide for you what books you can read? What music you can listen to? What speeches you can hear? What movies you can see?

There’s not an angel in this world in whom I would entrust that power to censor.

But it’s never about censoring for me. It’s always for the other guy. We always think that other people will be led astray by arguments — that other people are not sophisticated enough to be able to rebut arguments.

One of the things that you find about arguments for censorship is that if you know enough history, they’re ancient arguments.

Arguments you see today about banning books related to critical race theory — saying that it harms our children — are no different than the arguments that were being made in the 1940s and ‘50s about how comic books were resulting in juvenile delinquency and harming children.

Or about the printing press. They wanted to ban books. They said the masses wouldn’t know what to do with books; they wouldn’t understand truth from falsity; they would lose their faith if they were confronted with criticisms — like the whole Protestant Reformation.

And maybe the Catholic Church was right about that.

But that’s what happens with every new technology. We’re seeing it happen with social media right now.

Another big argument is that words are violence. That words cause stress, and stress prolonged over time causes trauma, and that has deleterious physical effects on us.

Those arguments come from the ‘70s, ‘80s, and ‘90s. It’s Catharine MacKinnon [author of Only Words, in which she argues that America’s free speech laws entrench inequality]. It’s Richard Delgado [co-author of Words that Wound, which argues that America’s free speech laws are rooted in racism].

Those aren’t new arguments, but if you buy them, well, okay: Words are stressful, and stress can produce trauma, and trauma can cause physical pain. So then is my argument with my wife that lasts a week violence?

And if words are violence, doesn’t logic dictate that you can respond to words with violence?

It’s a slippery slope down to authoritarianism and fear.

These are the arguments you hear, and there are more, but they’re old arguments and they’ve been posited before. They’re just being applied to new speech or new times.

What you’re saying about the Bill of Rights and its purpose brings to mind John Stuart Mill and his writings about the tyranny of the majority.

When John Stuart Mill wrote his seminal 1859 book On Liberty against that sort of majoritarian rule, he wasn’t talking about the law. He was talking about the stultifying conformity of Victorian England and how it prevented talking across lines of difference and exploration of ideas. The dogmatic orthodoxy within society was stultifying to creativity, innovation, and progress.

In America we have this very strong and robust First Amendment right. We say that we defend free speech because the First Amendment protects it. But that’s a circular argument.

Why do you want free speech in the first place? Why should the First Amendment protect it?

Part of our goal at FIRE is to make the cultural arguments that are necessary to sustain the constitutional rights which, without broad-based support, end up becoming only a “parchment barrier.”

Do you think there is more anti-free speech traction now than there was 10, 20, 30, 40 years ago? How is it trending?

I don’t think it’s easy to say. Throughout the 20th century, you had the political left strongly in support of free speech. You see this today with old school liberals like Ira Glasser.

But they were strongly in support of free speech because they saw what was happening with civil rights marchers. They saw Tipper Gore trying to censor artistic expression when she pulled Dee Snider [of Twisted Sister] and John Denver in front of Congress to testify about heavy metal music.

Over time, those battles were won. They are never won completely, but they got the Supreme Court to be more protective of free speech than probably at any point for any nation throughout human history.

Then many people against censorship got into power, and they then suffered from the censor’s curse.

The censor’s curse is when even strong free speech advocates, once they gain power, see censorship as a convenient tool to get what you want. And so, in higher education, in the media, even in big tech, conservatives saw themselves being censored.

So free speech advocates for a short time have had a marriage of convenience with conservatives in pushing back against censorship.

But now conservatives see “woke” as the big boogeyman. And in states where you have conservative controlled legislatures like Florida or Texas, you see them passing laws to go after the ideas they find most objectionable, like critical race theory, or “wokeism,” as they call the concepts.

The one through-line that you find is that people are always looking to censorship as a tool to go after their opponents. And those opponents are always looking to free speech to defend themselves.

When things swing one way, they have a tendency of swinging back. If I look at any one decade, maybe it’s liberals for whom free speech is the cause of the day. The next decade it might be conservatives. It just depends who’s in power, and who needs free speech to fight the people in power.

How do you look at the arena now?

Freedom speech is in a weird place. We had that marriage of convenience with conservatives in recent years, but conservatives now have a power in institutions that they didn’t before. And now they see D.E.I. [Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion] and woke and C.R.T. [Critical Race Theory] issues as being a bigger threat than the censorship of conservatives in higher education, for example. And now they’re using those same tools that they once opposed to advance their interests.

So how do we get to a society with a good base in reason instead of rampant idiocy and delusions?

Censoring ideas allows conspiracy theories to enter. Do we want the government deciding what is true, what is false? Yeah. Uh, they can certainly make the case for it, but under penalty of prison or deplatforming or collaborating with private actors to censor is very, very dangerous.

I’m sympathetic to concerns about the existence of falsity in our society, but I’m more concerned about some of the tools that are used to combat it.

The best we can do in a free society is confronting false speech with the truth. Not with censorship and more conspiracy.

And civic literacy. Right?

Let’s teach people how to understand what makes a reputable news source. How do we bolster our arguments in a free society? What does a good argument look like? And what does a bad argument look like? How are we looking for facts? Let’s not privilege perceived authority — let’s look at the data.

Censorship is a quick fix, but it isn’t the long-term fix. It prevents us from knowing what the problems actually are. That’s dangerous.

So more instruction in logical and critical thinking?

Yes, that would be helpful. And forcing people through our educational systems to engage with people they disagree with: to learn how to think through counterarguments and rebut them.

I feel like we’re teaching a generation easy tricks for getting out of an argument, saying, “It’s a concern, but that’s liberal.” Or “That’s just a white male talking.”

These are ad hominen attacks: easy tricks that are unfortunately gaining credence in our society and preventing people from learning how to confront ideas.