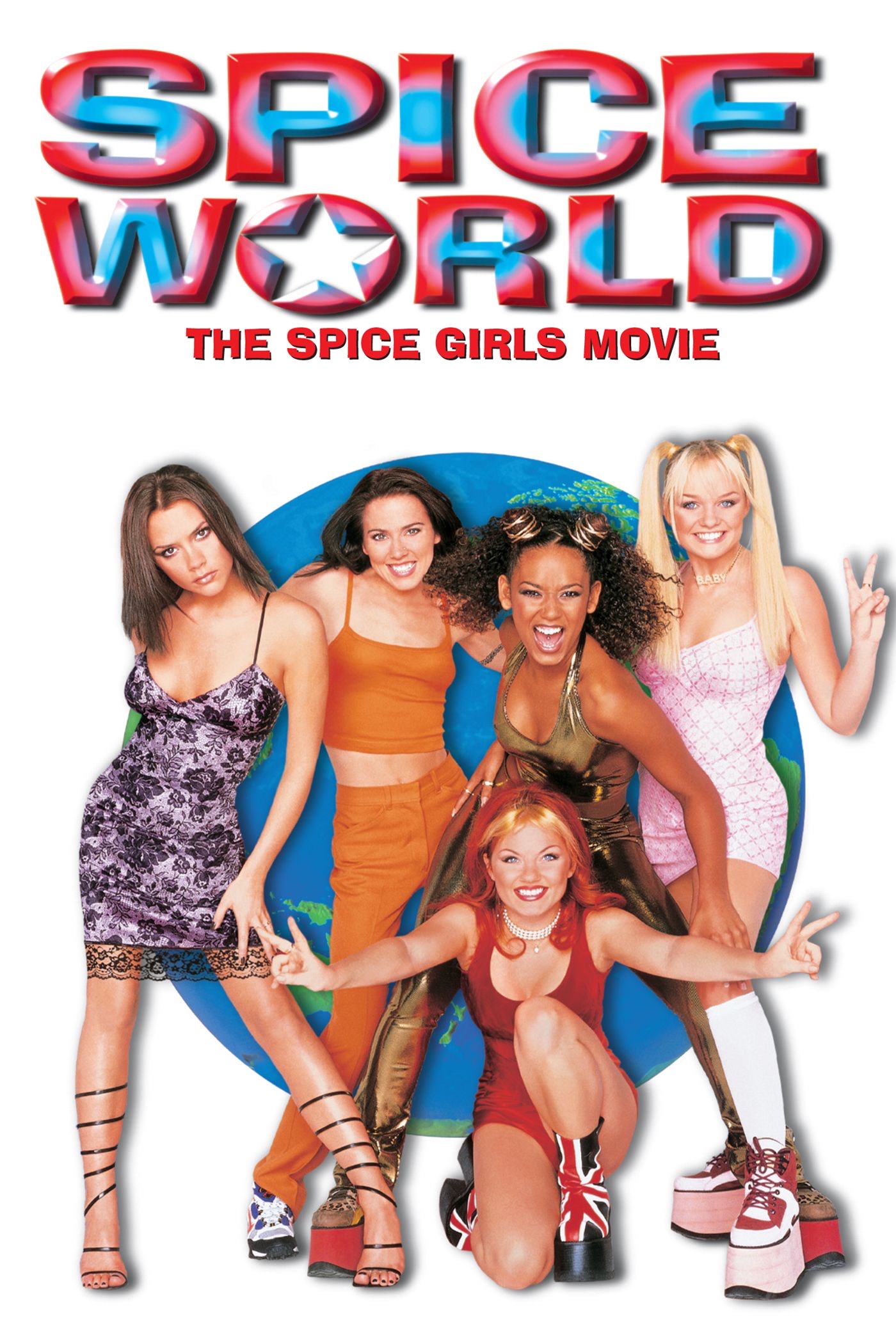

On January 23, 1997, Columbia Pictures dumped Spice World in US theaters, roughly a month after it premiered (as it should have) in the UK. A mockumentary capitalizing on the delirious success of the British teen pop group the Spice Girls, manufactured as the femme response to the boy band craze of the ‘90s, their ironic tagline boasted: “They don’t just sing,” which, of course, courted the expected critical derision in the trades.

Hardly as beloved as their albums, it arrived in the midst of the celebrated sweet spot of their popularity, and eventual hobbling, only several months later, thanks to Geri Halliwell’s surprise exit. Although assembled in the spirit of The Monkees, they were the most significant musical sensation out of the UK since the Beatles, though lacking the cultural staying power of their predecessors. There was further disparagement in comparisons to Richard Lester’s A Hard Day’s Night (1964), the beloved swinging sixties artifacts which remains revered while Spice World’s tongue-in-cheek time capsule is better remembered on lists like “The 100 Most Enjoyably Bad Movies Ever Made,” at least according to The Golden Raspberry Awards (a.k.a. the Razzies).

Looking back, Spice World serves as a wonky prototype for the kind of pop-reality personalities which would proliferate television superstardom consumed by aging millennials, and the technology-defined reality of the social media-nursed Zennials. And while not exactly ripe for recuperation, it’s a film which was a bit more savvy and lovable than elder prognosticators immediately determined, marrying icons and false prophets in a zippy film which wasn’t ever really giving more than its main players professed to offer.

Also Read

9 Can’t-Put-Down Music Memoirs of 2022

Spice World was actually the second film directed by Bob Spiers in 1997. Coming off his Christina Ricci-led remake of That Darn Cat, Spiers was approached with the project purportedly not knowing who the musical group was. Convinced by his Absolutely Fabulous collaborator Jennifer Saunders (who has a wink-wink cameo being rude to Victoria Beckham, then Victoria Adams) to take the gig, the script is credited to Kim Fuller (who has the distinction of also having penned 2003’s From Justin to Kelly), but the final product suggests a lot of improvisation and rushed edits (such as excising mention of the recently deceased Princess Diana and then as a means to distance itself from Gary Glitter, arrested in 1997 on child pornography charges). The gossamer thin plot finds the Spice Girls performing “Too Much” before immediately vocalizing their difficulties with newfound fame and fortune. As they travel London on a double-decker tour bus driven by Meat Loaf (wherein a non-functioning toilet explains a trip to the woods for a group urination and surprise meet and greet with alien fans), they prepare for a performance at the Royal Albert Hall. Unbeknownst to them, an irate newspaper owner, Kevin McMaxford (Barry Humphries) employs a photographer, Damien (Richard O’Brien, best known as Riff-Raff from The Rocky Horror Picture Show), to catch the women in a compromising situation so he can tarnish their reputations. Simultaneously, Piers (Alan Cumming) is toggling around with his film crew in pursuit of the group for a documentary project, while their manager Clifford (Richard E. Grant) is fielding inane ideas from two Hollywood screenwriters for potential film projects featuring the Spice Girls.

Not unlike A Hard Day’s Night, one might have to be of a certain age, or a particular mood, to enjoy the jocular frivolity such films employ. But Spice World was routinely dismissed, if not downright ravaged, by the critical gatekeepers. The usually somewhat diplomatic Roger Ebert was exceptionally cranky, accusing the women of not being able to lip-synch to their own songs, and concluding “the Spice Girls could be duplicated by any five women under the age of 30 standing in line at Dunkin’ Donuts.”

Such blasphemy hardly plagued the fanbase, with the film raking in $100 million at the box office and breaking records for highest-weekend debut for Super Bowl weekend.

What’s lacking, as far as the film’s legacy, is its failure to have any distinctive longevity, maybe because the group’s kismet was violated only several months after the film’s release, and maybe because it was tethered to an industry where such saturation and popularity is a disguised death kiss to creative endurance. As a film, it was hardly worth such derision, clearly trying to be fun and frothy while peppered with a ton of notable British cameos who all apparently wanted access to Spice Girls merch to give to their tween relatives. What’s not to love about a strange Bob Hoskins or Elvis Costello appearance? Or a dapper Roger Moore as an industry demi-god with a menagerie of animals at his disposal. Doing more of the heavy comedic lifting are some under-appreciated performances from Cumming and Grant, proving, as they usually do, how to turn a potentially throwaway role into a charismatic display.

Part of the innate appeal of the Spice Girls was their marketing and manufacturing, presenting a quintet of ladies who were branded with ‘unique’ attributes, allowing space for there to be “someone” for “everyone” to like. Never mind what these labels were exactly, though why Mel B., the only Black member of the group, had to be “Scary” uncomfortably channels the colonialist traditions of early Hollywood depictions of African stereotyping, such as dangerous and mystical voodoo priestesses (her anointment as the “scary” one even supersedes the troubling subtexts of Marlene Dietrich donning a gorilla costume while singing “Hot Voodoo” in 1932’s Blonde Venus).

The group’s vague but imperative incantation of “Girl Power” rests somewhat uneasily atop their inherent sexualization, a mantra eventually left in the dust considering how the press treated female pop icons in their wake, like Britney, Christina or the Paris Hilton/Lindsay Lohan drama of the mid 2000s. Fashioned as filling a void in response to an industry saturated with boy bands, the Spice Girls were a veritable prototype of things to come. However, they’re lodged indefinitely in ‘90s aesthetics. While something like Danny Boyle’s Yesterday (2019) revolves around a plot where everyone has forgotten the Beatles except one man, suggesting enough of an inescapable iconicity to generate a recognizable cultural given, there’s hardly the same comprehensive acknowledgement in support of the Spice Girls (although ABBA did release an album forty years after their pop sensation heyday, so, you never know).

Like a time capsule perhaps needing to stay buried a bit longer, each group member represents a particular stereotype, some more troubling than others. Mel C as “sporty” suggests athletic women are inherently butch, while Emma Bunton’s “baby” channels the doll-like Susannah York in The Killing of Sister George (1968), defined by youth, immaturity, and manipulability.

Victoria Beckham’s “poshness” has aged the worst of the bunch. Constantly mean-mugging and undeservingly surly, it’s unclear what’s exactly “posh” about her, but she provides a template for a world eventually to be saturated by the Kardashian clan and their equally questionable abilities beyond cosmetic vapidity. It’s probably most difficult to describe what exactly Geri Halliwell’s skillset was to the uninitiated (i.e., Billie Eilish), nicknamed for the color of her flaming mane of clown-red hair speckled with white bangs resembling a vat of crab legs at a seafood buffet.

And yet there they all were, poking fun at themselves as much as they were the overproduced industry which brought them to fruition as mysteriously as Zeus birthing Venus from the sea. In one scene, they discuss the difficulty of these labels, each of them switching personas in a corny montage. But these weren’t the concerns of the teenage fanbase who obsessively consumed them through their music and their merch.

1996’s Spice had the distinction of being the first CD I had ever purchased for myself, at twelve, making my mother put replay limits on “Wannabe” whenever she drove my younger sister and I around in her Jeep Grand Cherokee. And while my parents rolled their eyes — for various reasons — about the Spice Girls, sometimes we’d get to extend that limit by a few plays. In short, it was more difficult not to like Spice Girls in the late ’90s. Looking back, their lyrical content wasn’t nearly as juvenile or shallow as they’ve been routinely trivialized as. There was a sense of unity and invitation, which likely enhanced their enduring popularity amongst gay men even more than a generation of young girls who moved on to consume similar artists. Their lone cinematic offering is silly, sweet and likely most meaningful to those captivated by them while in their youth, and represents a kind, loving snapshot of a time and place. Never seeming like they weren’t aware of their critics, singing “I’d rather be hated than pitied” in “Naked,” the joke’s on the naysayers, including Mr. Ebert, who arguably wasn’t qualified enough to look past his pretensions to divorce his disdain for their music from the purposeful (and at least semi-successful) frippery of escapist fan fiction.

Watch Nick and his husband Joseph review (and spoil) films on their YouTube channel, Fish Jelly Film Reviews. Their podcast of the same name is available everywhere.