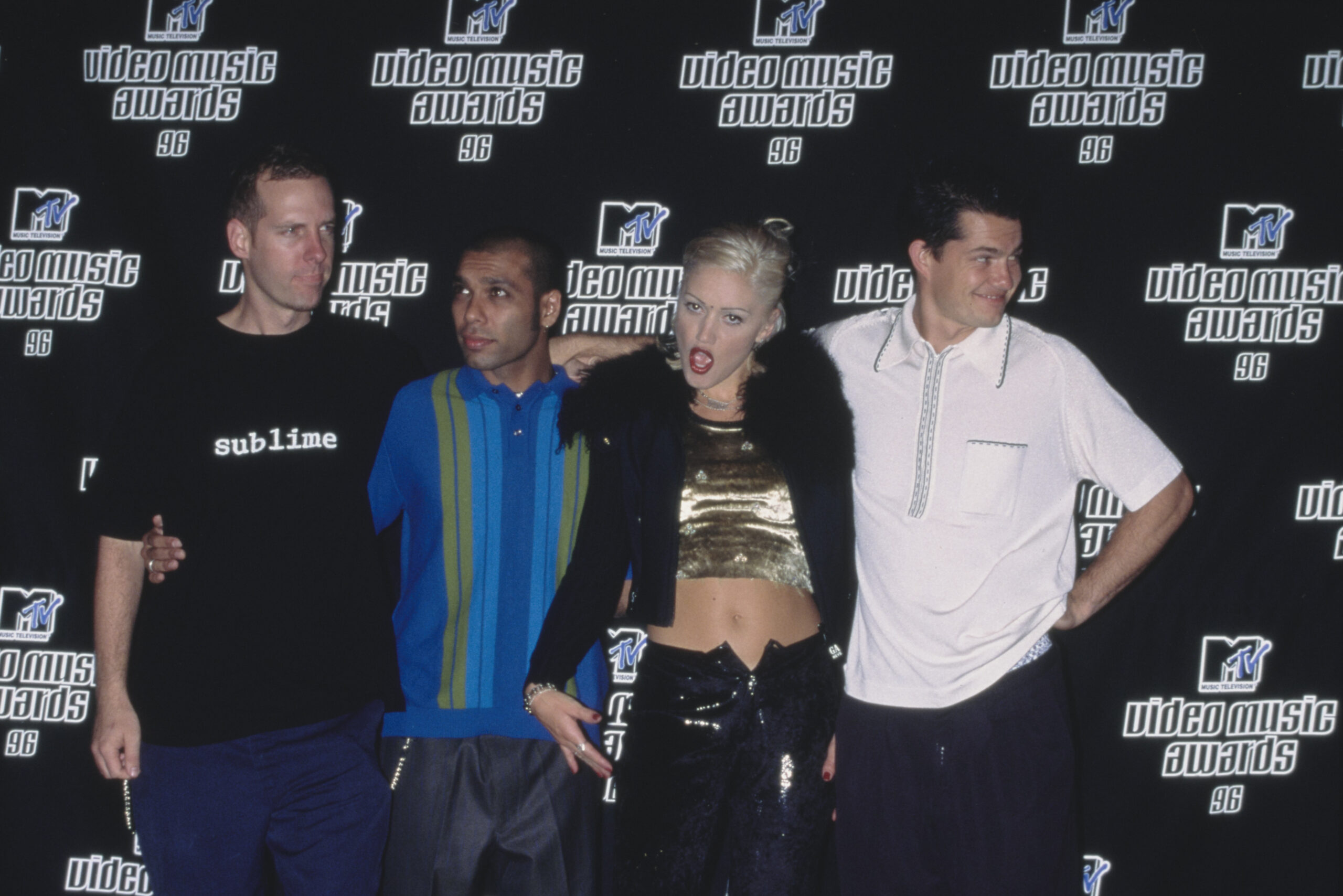

This article originally appeared in the November 1996 issue of SPIN.

A tragic suicide. A messy inter-band romance. A flop first album. Gwen Stefani and No Doubt have suffered enough heartbreak to feel your pain, they’re just not at all interested in replicating it. Finally, exclaims Jonathan Bernstein.

I guess the correct term is “Gwennabees.”

Smatterings of breathlessly excited, blonde-streaked, sparkle-lashed 14-year-olds litter the backstage area of San Francisco’s fabled Fillmore. Oblivious to the portraits of Janis, Jimi, and the Jefferson Airplane scattered around the venue, these girls line up to press tokens of esteem on the recently adopted object of their devotion, No Doubt’s bare-midriffed, high-octane, dreamboat frontwoman, Gwen Stefani. “You inspired me to start my own skateboarding magazine for girls!” enthuses one such acolyte. Then she presents the 26-year-old singer with a painting, thankfully explaining the elements contained therein—”That’s the sky, that’s the river, that’s the castle”—and before anyone can ask “Uh, what is it, exactly?” Stefani gushes gratitude and holds the piece out to me. “Isn’t this amazing?” she gasps. Of course, I find myself with a headful of retorts of the “I can’t tell till you wipe the vomit off” variety. I search Stefani’s eyes for a glint of cynical complicity, find only earnest appreciation, and, feeling like a grinch, mumble, “Interesting. Very unique.” Another devotee pleads to use the phone in No Doubt’s dressing room. Against the advice of the group’s road manager, Stefani lets the girl in. She rushes to the phone, dials seven digits, and shrieks “I’m in No Doubt’s dressing room!”

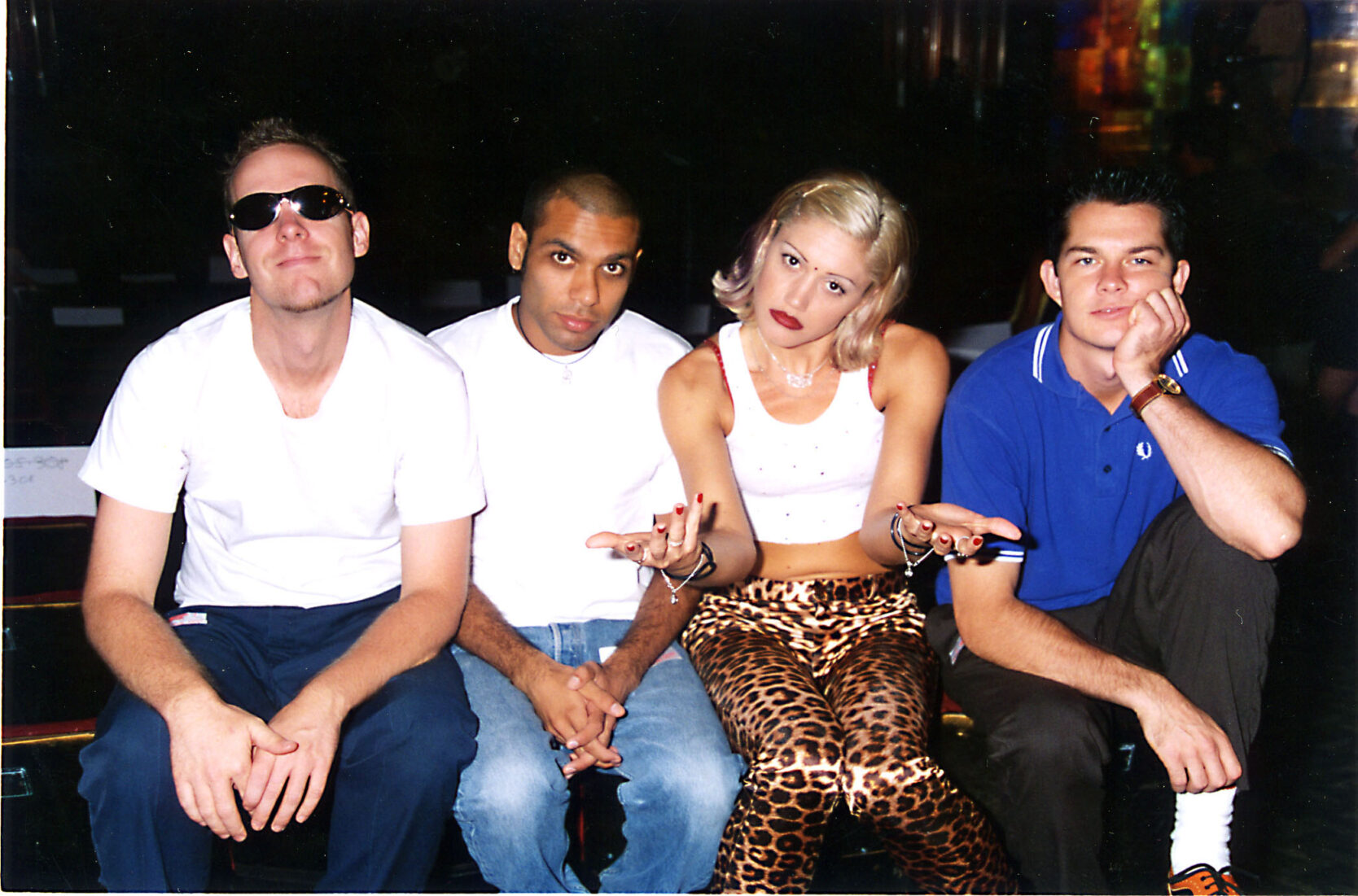

Such heartwarming scenes of girly empowerment, acted out nightly and with increasing glee during No Doubt’s unlikely climb to stardom, must no doubt be growing commonplace, maybe even tiresome, to the boys in the band: bassist Tony Kanal, drummer Adrian Young, and guitarist Tom Dumont. Once the changing area is finally cleared of teens spirited, the four members of the group slump into a business-as-usual posture, and the Fillmore dressing room takes on the tone of just another stop on their nine-year uphill trek.

“I don’t know whether to wear this onstage or not,” frets bassist Tony Kanal. “How does it look?”

Silence.

“You guys, can I get some feedback here? How do I look?”

No reaction.

Stefani sits in the corner wrapping yards of gauze around the foot she broke during a typically combustible performance the previous month. Kanal, meanwhile, doggedly solicits opinion on his choice of onstage apparel, a billowing striped gray jumpsuit that conceals any evidence of crotch and butt. “It’s polyester,” he grumbles. “I’m sweating already.”

“I think you look cute,” says Stefani, finally, looking up from ministering to the throbbing foot that has earned her a Kerri Strug-like reputation for grace under duress.

“You look like Woody Allen in Sleeper,” smirks Young, whose own visual hook—hair slicked up into devil horns—has recently been shorn into a flat-top. The jumpsuit is jettisoned.

Showtime approaches. And despite the whiff of lethargy hanging over the hallowed room, this clearly isn’t just another stop on the trek. The fifth date on No Doubt’s first-ever tour as a headliner, a double-platinum-plus-and-rising album under their belts, this is major. In recognition of their altered status, the group links arms for one of those arcane collective motivational psych-up rituals. Kanal gives me a look. I make to leave. “You too,” he says. I link arms with No Doubt while they recite their aims for the rapidly approaching show. “Last night was great. I want to take this one to a higher level,” says Kanal. “I just want to enjoy myself because I’m totally selfish,” giggles Stefani. “I’m not going to dance tonight,” promises Dumont. I mumble something about attempting to be less tardy with my rent check. The quartet breaks out of the circle, slam their fists together and, in unison, emit the cri de coeur “No Doubt!”

Myself, I had doubt. Two fists full. My first fleeting impression of No Doubt was gleaned from their gaudy presence among the maudlin, slope-shouldered worry warts enjoying MTV rotation. “Who are these prancing nincompoops?” I wondered. “Who is this buff blonde with the dot on her forehead who looks like she’s just been peeled off the side of a WWII bomber?” I harbored such questions because I didn’t quite get No Doubt right off the bat. I failed to immediately ascertain that they trafficked in a commodity called Entertainment. I forgot—and, after the onslaught of rock’s funereal last five years, who could blame me?—that groups could be fun, and if they were fun that didn’t automatically make them pariahs or confidence tricksters. I knew what I had to do. I went back to the smash Tragic Kingdom, with its rinky-dink keyboards, farting horns, staccato guitars, and vibrato-spattered vocal gurgles, quacks, and squeals. I removed it from the company of Live Through This, Little Earthquakes, and Exile in Guyville, where it stood out like an artfully manicured sore thumb, and filed it next to Parallel Lines, Beauty and the Beat, and She’s So Unusual. That manner of hook-strafed, femme-fronted, quirky radio fodder was once in heavy supply. Now it’s available from a solitary source. No Doubt is the Last American New Wave Group.

It should come as no surprise that Gwen Stefani and No Doubt hail from the last bastion of Anglophilia. Somewhere between the endless blue sky and the manicured lawns of suburban Southern California lurked a lingering discontent that led a generation to seek solace from a colder climate. Countless Cali teens spent their formative years crying in the sunshine to British doomsdayers like Robert Smith, Siouxsie Sioux, and Dave Gahan. The less pallid and passive in the audience spiked their hair and attempted to modulate their vowels in accordance with the rules laid down by the Anti-Nowhere League, the Exploited, and GBH. Others, taken by the porkpie hats, ticking-clock rhythms, checkerboard apparel, and “Rude Boy” pins of England’s 2-Tone movement, adopted ska as the soundtrack to their lives.

Eric Stefani of Anaheim, Orange County, California, was one of the latter group. Among the oddities he brought home from the local import bin was the picture-sleeved seven-inch Stiff single “Baggy Trousers” by Madness. For Eric’s little sister, Gwen, that record was a revelation. Ask her now about her teenage years and she’ll flatly retort, “In high school, the only thing I was really into was Madness.” She fell for their vaudevillian swagger and the way they dealt with the bleak mundanities of everyday English life—taking the bus, standing in the rain, the British school system—all housed in a romping environment.

“When I get into somebody,” says Stefani, “watch out, because, like, I’m into it. I think about him the whole time.”

A Loara High School classmate, John Spence, was similarly stuck on ska and it was he who, in early 1987, motivated the Stefani sibs to form a band. The core of Eric’s keyboards, Gwen’s teeny harmonies, and Spence’s hoarse bellow, plus a few makeshift musicians, popped up at various Anaheim parties. “We sucked,” recalls Gwen, “but for some reason there was automatically this built-in following. People loved the fact that it was a girl, that it was 2-Tone, that it was me and John up there.”

Tony Kanal was born in India, raised in England, and was relocated to California at age 11. He saw No Doubt in their party-band incarnation, heard they were looking for a full-time bass player, and, by the time the group played their first promoted-and-paid show, had become a permanent fixture. Five months later, he was both the group’s manager and Gwen’s boyfriend, neither of which position he currently maintains.

In December 1987, Kanal received a phone call from Eric Stefani: “He just said, ‘Come over right away.’ I got there and he said, ‘John’s dead.’ He shot himself in the head.”

“There were some problems there,” recalls Gwen. “He was kind of in and out of high school. His mom kept taking him out of school. He wasn’t really in with a bad crowd, but his mom was really paranoid about it. For all the years I knew the guy, I only went to his house one time, but compared to my family, The Brady Bunch family, church every Sunday—it was different.”

Alan Meade, described by Gwen as “a disco-smooth dork,” took over on vocals until he purportedly got his girlfriend pregnant and left the band to get married at 17. That left Gwen as sole proprietress of vocals. Tom Dumont, who along with his sister laid down the screaming twin leads for Anaheim metal-lurgists Rising (“That’s Rysing?” I ask, hopeful. “No, two i’s. We didn’t go all out”), joined the group in 1988. Longtime No Doubt audience fixture Adrian Young became the full-time drummer next year.

The group’s burgeoning reputation as a festive live spectacle attracted niblets of label interest, but it wasn’t until Tony Ferguson, a Brit who used to work at Stiff, home of the hallowed Madness, and who now labors in an A&R capacity for then-just-debuted label Interscope, that anyone took a serious look at No Doubt. Ferguson brought along Jimmy Iovine, Robert Cort, and Ted Field, the industry heavy hitters behind lnterscope, to see the group.

“Jimmy told someone, ‘That girl will be a star in five years.’ That was in 1991,” marvels Gwen.

“It wasn’t a scientific insight or anything,” says Iovine, a music-biz vet whose presence as both a producer and label boss has loomed large in the careers of John Lennon, Bruce Springsteen, Dr. Dre, and Trent Reznor. “They were young. I knew they needed a lot of work. Five years was just a figure. I can’t believe she remembers that.”

Glaring proof that luck laughs at No Doubt came when they set to recording their Interscope debut at the exact same moment that a pungent gust from the Pacific Northwest was about to render their peppy skank about as welcome as a melanoma on prom night.

Packed with reedy rhythms and novelty songs, No Doubt’s self-titled first album was released in 1992. It was instantly embalmed by Interscope. The label withdrew tour support and refused to give the group a green light to record a second album. “But we never lost faith in the ability of Gwen Stefani to become a star,” insists Ferguson.

At the end of 1994, the band finally got the go-ahead to make another record. The album that would be known as Tragic Kingdom remained in a cryogenic state of artificial existence for a year after its recording. During that time, Eric Stefani left the group—he now works as an animator on The Simpsons—and Kanal relinquished his duties as Gwen’s boyfriend.

Paul Palmer, who had just mixed labelmates Bush’s Sixteen Stone, was drafted in to apply similar sonic skills to Tragic Kingdom. “I thought they were fantastic the minute I heard the music. It was all there, even in its roughest stages,” avows Palmer, who was not only a studio doyen but also co-owner of the boutique label Trauma, which had just gone into partnership with Interscope. “I had a feeling about the band I couldn’t let go of.”

In the first sustained slice of good fortune to waft No Doubt’s way since the dawn of the ’90s, Palmer’s enthusiasm saw the group shifted from Interscope to the nurturing environs of Trauma, where they were, at the time, one of only three bands on the label. Tragic Kingdom was released in October of 1995. Buoyed by visible record-company support, the group set out on tour, which, a year later, is where they remain. Their sweat has borne fruit in the shape of inescapable airplay for “Just a Girl” and “Spiderwebs,” and the Top 10 presence of Tragic Kingdom. “I can’t believe this is my life,” gasps Gwen. “This is my loser band?”

“You don’t have to be singing songs about angst and pain to be credible,” says Tony Kanal. “We’ve gone through just as much stuff as any band. We just don’t choose to sing about it.” He pauses and thinks about his last statement. “Well,” he amends, “maybe we do choose to sing about it.”

“I forced Tony to go out with me,” says Gwen Stefani. “He wasn’t even interested. When we made out that first night, I think he thought it was more of a one-night kiss. But then we started going out and after the first year, I was going ‘When are we getting married?'”

Among the album’s kaleidoscope of styles, moods, and tempos lurk songs celebrating individuality (“Different People”), songs expressing demographic empathy (“Sixteen”), and songs about living in the shadow of Walt Disney (“Tragic Kingdom”). Mostly, though, Tragic Kingdom is filled with Gwen and Tony songs. Specifically, Gwen-Left-Broken-Hearted-by-Tony songs. Vengeful declarations of independence (“Happy Now?”), tear-stained refusals to accept the inevitable (“Don’t Speak”), and vain attempts to cling to a few shreds of self-respect (“End It on This”). Like Fleetwood Mac and Abba before them, the group’s success has both come at the expense of and has openly exploited the heartbreak of a central couple. But while Lindsey Buckingham could pen a stinging critique of Stevie Nicks’s perfidy and flakiness (“Go Your Own Way”) and then force the object of his derision to mouth his words, in No Doubt, it’s the otherwise sweet-natured singer who nightly picks the scabs off old wounds for public consumption.

“When we broke up, I still forced Tony to kiss me,” says Gwen. “I was in denial. I might have lost the title of girlfriend, but in my eyes we were still together. For, like, a year, he didn’t have to come to my house when I demanded it. He didn’t have to do anything, but when he felt like it, I was there. It was horrible.”

As female revenge scenarios go, Stefani has landed in an unbelievably juicy position. Imagine, as a dumpee, you wind up worshiped and adored for warbling songs that berate the dumper. And he has to stand there and play those self-same songs! “It’s fucking surreal,” says Kanal. “Think about being onstage playing these songs. I’m opening my personal life up to all these people. But I just can’t get attached. I’ve got to separate myself from the music and lyrics.”

“At first it didn’t seem to get to Tony,” says Dumont. “He was like, ‘I don’t know, for some reason it doesn’t bother me that all these songs are about me.’ Maybe he liked it. But now I think it’s starting to bother him a little. Some guy wrote an article about us saying, ‘Why is Gwen so sad? What did Tony do to her to make her write all those lyrics?'”

While Stefani admits to phoning Kanal and reciting the lyrics to “Happy Now?” (“Are you happy now? / You’re by yourself / All by yourself / You have no one else”), this self-admitted Woman Who Loves Too Much maintains intense loyalty to her ex. “Everybody’s like, ‘God, that guy is a jerk,’ which is not fair because he didn’t have his lyrics to talk about me when I smothered him and he didn’t have a life. It must be hard for him to take when people write ‘How could you leave Gwen, she’s so great.’ But they don’t know me. They don’t see my faults. They just see me however they want to see me. They think I have abs and I don’t. I have fat.”

Lucid and loquacious when holding forth on subjects ranging from No Doubt’s checkered path to Prince’s far-reaching ’80s lineage (he bests me with Tamara and the Seen, I call his bluff with Jill Jones), Kanal’s speech is peppered with pregnant pauses when discussing how he and Stefani found themselves taking up residence in Splitsville. He glances out of the window of the Seattle hotel restaurant where we’re having breakfast. Out on the patio, a wedding is in progress. He watches the couple take their vows and it’s possible he’s hearing Stefani’s oft-repeated plea “When are we getting married?” and maybe wondering if she’s up in her room watching the ceremony, maybe even tensing himself for the prospect of her charging across the patio in time to catch the bouquet. He turns back from the exchange of rings and ponders his perception as something akin to a ska-punk Ike Turner.

“It’s very tough,” he admits. “I care about her a lot. I’m not given the opportunity—nor do I want it—to write my own lyrics. But hopefully people with some logic will realize that it wasn’t just me, that it’s not just a one-sided thing. I’m not such a bad guy.”

Stefani claims her post-Tony love life has not been a densely populated affair. But there were those rumors linking her to tousle-headed labelmate Gavin Rossdale. “Everyone wants to know about me and Gavin,” she smiles. “We’re just friends. Although he’s definitely cute.” Pondering the dichotomy between her naturally self-deprecatory nature (the inside of her vanity case is festooned with stickers bearing the word DORK) and her sudden ascension to paragon of bare-midriffed yumminess, she continues. “A lot of boys like me now. But it’s not like I’m making out with people, you know, ‘Hey baby, come back to my room.’ I’m the kind of person who would way rather just spend time with my boyfriend watching a movie at home than going out to a party. That’s the way I’ve always been. I’m not used to being on my own, to not having a boyfriend. When I get into somebody, man, watch out, because, like, I’m into it. I think about him the whole time.”

Turning plaintive, she sighs, “I want to have a time when I don’t need a boyfriend. But it’s just nature to want someone. There’s nothing better than that.” She pauses for a second then leans towards me. “So what did Tony say about me?”

If existing in an unattached state is taking its toll on the singer, the rigors of the road have left a similar mark on Dumont and Young. As Gwen and I head down to the Quality Inn hotel bar, we come upon the guitarist and drummer locked in each other’s arms, swaying to in-house one-man band Steve Merriam’s haunting rendition of Chris Isaak’s “Wicked Game.” Later that night, Young will tell me he’s counting the days till his girlfriend Christine joins him on tour. His anticipation is made more urgent because he smuggled a shoeful of mushrooms from Germany for the purpose of celebrating the reunion. As he talks, an inappropriately coquettish, over-40 Asian woman crisscrosses the bar, continually attempting to catch his eye, then making a big show of looking away and laughing. “It’s a lonely life,” he sighs.

Modern Woman, a beauty supply store in Bremerton, an hour outside Seattle, isn’t the most densely stocked outlet in the planet, but its displays of Wella and Clairol are sufficient to elicit an involuntary sigh of happiness from Stefani, who loads up with shampoo, conditioner, and lip-liner. “I just recently got ragged on for the girly stuff,” she says, referring to reviews that have taken her fondness for cosmetics and navel-displaying stagewear as compelling evidence to impeach her as the sort of pliant, submissive fuck toy of which we should have been long rid. “Maybe I should be more of a tough chick. But I’m not. That’s not me. I love makeup. I love getting my hair done. I love getting pedicures. I’m the furthest thing from a rock chick.”

Going on to tabulate further examples of Non-Rock Chickdom, she brings up examples such as her yearly trips to Knott’s Berry Farm to see the Ice Capades, her recent visit to Paris where she went jogging without money or I.D., got lost and had to call her father back in the States to find the address of her hotel and, most heinously, that she still happily resides at home (as does Kanal). “I don’t pay bills. I don’t pay rent. The only thing I pay is my phone bill and my car insurance.” She does, however, harbor vague notions of one day moving to L.A. “If my dad will let me.”

“I love makeup,” says Stefani. “I love getting pedicures. I love getting my hair done. I’m the furthest thing from a rock chick.”

Adrian Young rises from his hotel bed and glances at the golf bag propped up against his table. A dedicated player who prefers his time on the links to his hour onstage, Young’s been practicing for a radio station pro-celebrity game. “I was going to play today, but we’ve got a group meet-ing,” he says. “A lot of people don’t realize that this is a democracy. They’re like, ‘Ask Gwen if this mix is okay.’ Or we’re doing some TV show and it’s like, ‘Ask Gwen how this feels for her.’ I make fun of these people. I have to do something. I can’t fake it all the time.”

Probably the only starlike indulgence practiced by Gwen Stefani is her predilection for checking into hotels under the pseudonym “Darla Blue.” Nevertheless, her undimmable onstage kilowattage and generous allocation of Personality Plus has singled her out as the group’s Star-with-a-big-S. In the endless obstacle course of their nine-year career, the last and most potentially damaging impediment to No Doubt is that they’re now irreversibly engaged in a process to which experts refer as Becoming Blondie.

Like Chris Cornell, Kim Deal, Eddie Vedder, and, uh, Evan Dando before her, Gwen Stefani shines in a solo setting from the front cover of this magazine. Such public acknowledgement of a band member’s ascension from singer to Star-with-a-big-S caused heartburn for the rest of the group. “We want people to know that we’re a band” asserts Kanal, who is able to recount at some length the number of photo sessions in which he has participated only to open up the subsequent magazine and find himself cropped out. “For many years, we talked about what would happen if we ever got offered this sort of stuff. ‘We’re going to stick together. We’re not going to do it. We’re going to say “It’s the whole band or nothing.” ‘ But when you’re actually put in that situation and you see that your friend has the opportunity, maybe the once-in-a-lifetime opportunity, to be on the cover of a magazine, why would you hold someone back from that?”

“Everybody just wants to focus on the girl,” admits Stefani. “I think that’s the one outside stress thing that has come into the band. We’re getting over it. The others sit and bag on me constantly now. Like, ‘On MTV News, Gwen broke her foot last night blah blah blah…and in less important news, Tom Dumont was found dead.'”

“This crowd has not yet been rocked.” So pronounced Rob Kahane, co-owner of Trauma Records, gazing out at the vast expanse of pierce-holes and skate wear favored by the audience at Endfest, an annual internment camp with brief musical interludes, sponsored by Seattle’s modern-rock station, KNDD, “the End.”

The previous day, No Doubt had played a ramshackle acoustic radio session at the End. Stefani’s voice was ragged (“I’m being visited by a horse”), and Dumont’s playing hand was injured (“Someone asked for an autograph. Then, when they realized I wasn’t in 311, they grabbed the pen back and cut my hand”).

After the set, two starstruck Gwennabees approached Stefani, paying shy homage and asking for tickets to the upcoming dirt-bath. She apologized for being unable to accommodate them. They wandered off disconsolately. Then the group’s road manager said he could put them on the guest list. Stefani squealed “Little girls!” and scampered off after them. On hearing the news, they threw themselves at her like she had attained Fairy Godmother status in front of their eyes. “Work hard, stay in school, don’t kiss boys,” she cautioned them.

I don’t know if those girls were out in the crowd today. Part of me hopes not because they might have caught any kind of disease out there or, worse, the perfunctory sets by Everclear and Filter. But if they were bouncing around near the front rows, they would have seen No Doubt shine among the murk. They would have seen Stefani’s wackiest-ever rendition of “Just a Girl.” Downshifting from the song’s pogomatic power to a skeletal repetition of that niggling opening riff, Stefani adopted scaredy-cat eyes, a trembly-lipped pout—when Laverne wore a similar expression, Shirley referred to it as “the boo-boo face”—and a cowering posture. Whimpering “I’m just a girl” repeatedly, she prostrated herself on the stage, regressing back to infancy, looking like she might be huddled up in a steaming puddle of pee, until she screwed up her defiance and railed back at the ignorance and oppression of this manmade world under whose heel she’s squashed with a crowd-galvanizing “Fuck you, I’m a girl!” They would have seen Tony Kanal finally sporting his billowing striped gray jumpsuit. They would have seen the hulking brutes from Goldfinger and the Deftones herded on stage to sing along like happy campers with the group’s wedding-band encore of “Ob-la-di, Ob-la-da.” They would have agreed with Kahane when, at the show’s close, he declared that the crowd had finally been rocked.

“I never thought that me, this loser from Anaheim, could have any effect on anyone,” says Stefani after the show. “I never had any creativity or anything. Then, suddenly, I’m what everyone is looking at. It’s such a strange thing, but it’s so exciting, ’cause I remember the way those two little girls from yesterday felt. You have to keep it in mind, whether or not you feel like shit or whatever. You think that maybe if you bring a little happiness to these kids, they’re going to remember that. Like I would talk about Madness, they’re going to talk about No Doubt? How cool is that!?”