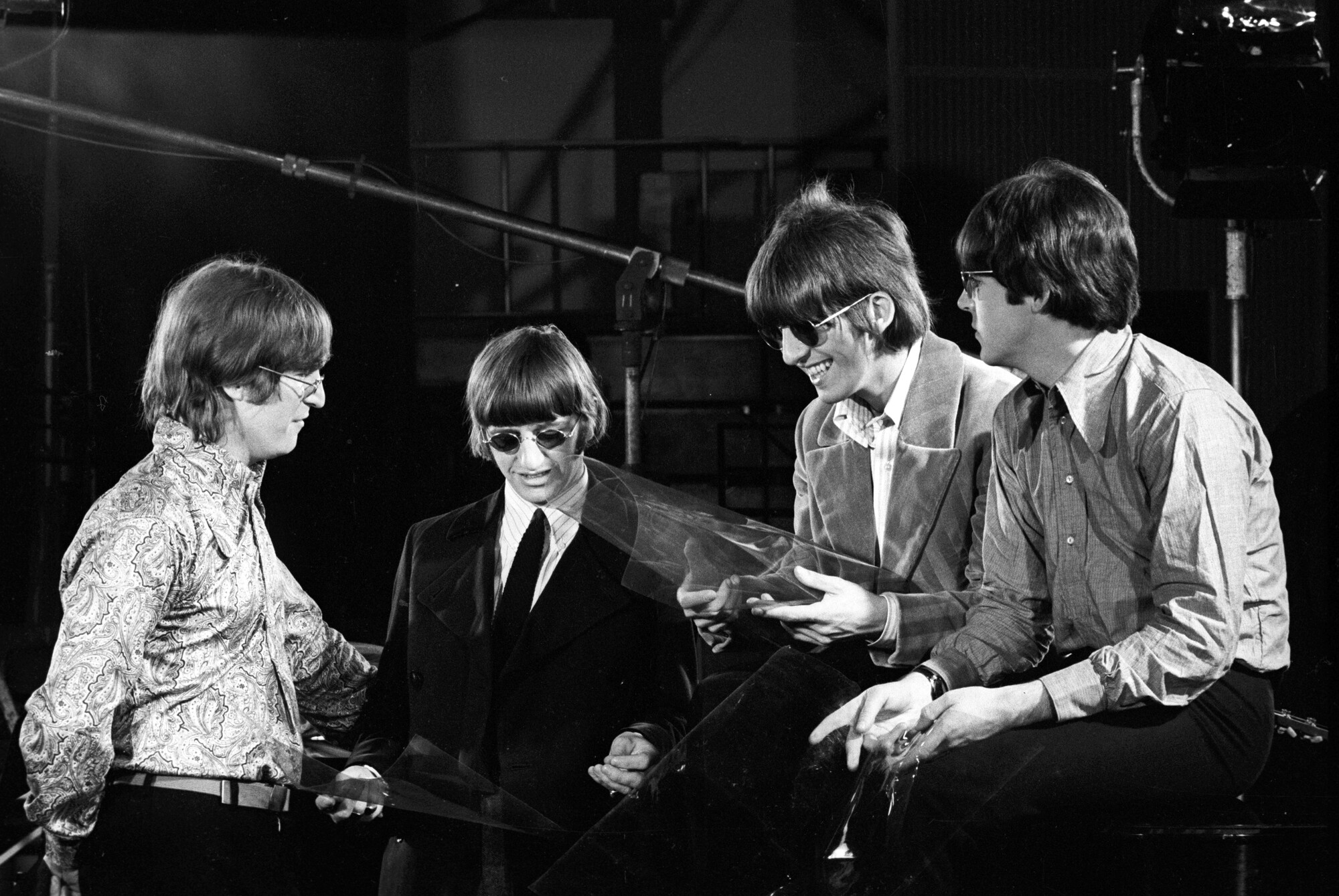

Those in the studio with the Beatles from April to June 1966, mainly George Martin, knew what the Scousers were up to. But imagine the perplexed looks from buttoned-down EMI executives when the band delivered their latest product.

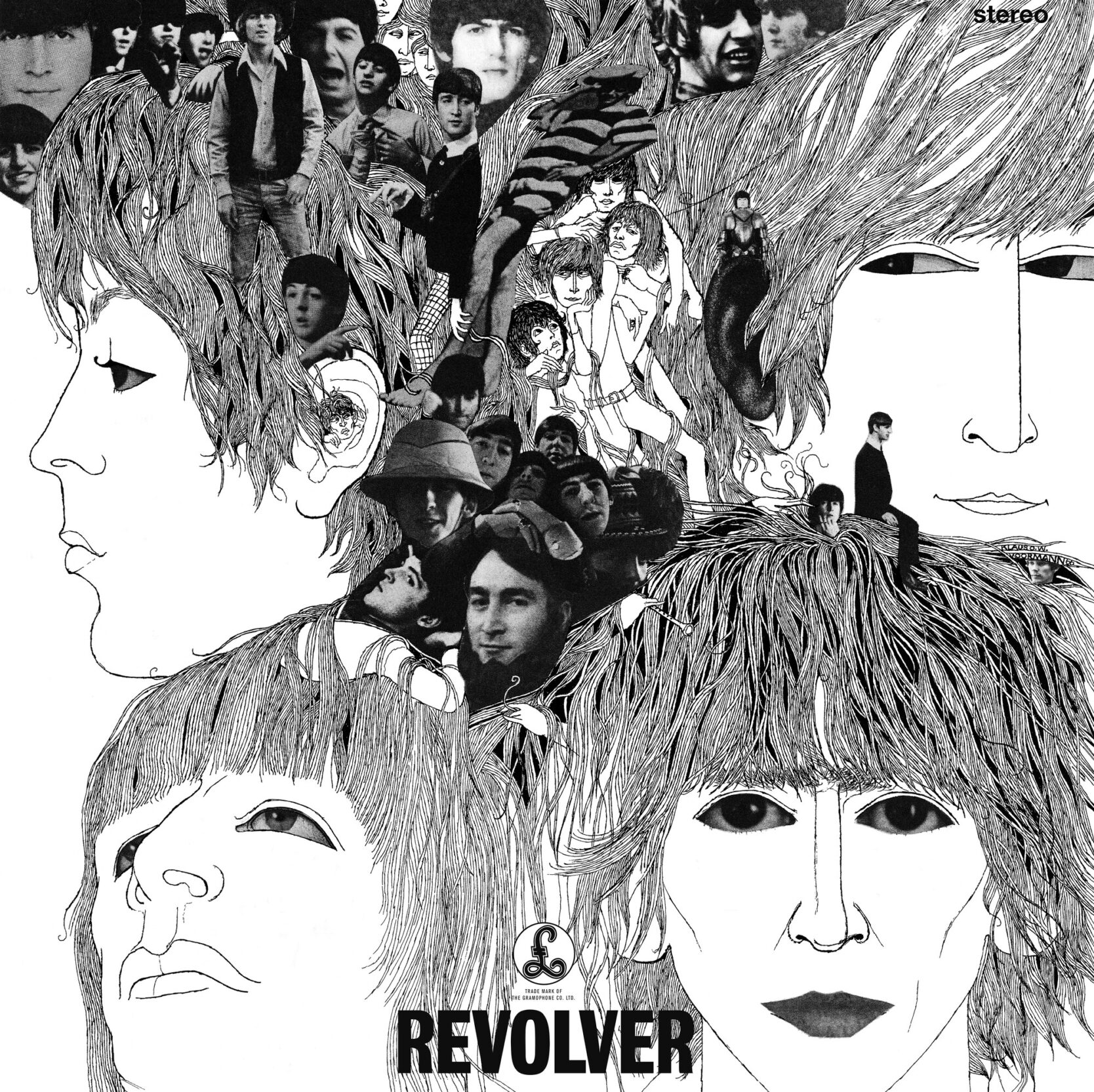

Revolver was the band’s most experimental work to date, filled with exotic instrumentation (the sitar), radical production techniques, children’s sing-alongs (Ringo would warble “Yellow Submarine” down the ensuing decades), and topics like taxes and drugs. What’s a record label to do?

It had been four months since their prior recording sessions, and that relatively open calendar pushed them further into the studio — and away from the grind of being pop stars constantly in the public eye.

“One thing’s for sure,” Lennon said a few weeks before the band’s studio return, “the next LP is going to be very different.”

He was correct — a fact illustrated by the album’s newly expanded reissue. The set, available in several editions, lets us poke deeper into the recording process through Giles Martin’s new mix and a treasure trove of unreleased early takes. Across 63 tracks, we are swept back to the accelerating arc of the Beatles’ creative prowess.

Martin (son of original producer George) has dialed back some of the controversial moves he made on earlier remixes, but here only purists will be stomping their feet. The super deluxe 5-CD edition, housed in a slipcase, is accompanied by a lavish, 100-page hardcover book that puts the whole shebang into context.

The mono version reflects how most listeners heard the original release; stereo was only beginning to get traction in the mid-’60s. The band worked meticulously to get that mix exactly right, leaving the seemingly inconsequential stereo version to the engineers. As such, hearing the original mono in this new context makes for interesting listening. There is something charming about its simple yet powerful pleasure, sounding as originally intended and heard by the band.

There is no film footage of the Beatles recording these songs, so we won’t have the experience provided in Peter Jackson’s eye-opening documentary Get Back. Nonetheless, the studio chatter on the two Revolver “Sessions” CDs gives us a voyeuristic perspective on the band’s creative process.

Prior to “Taxman,” the Beatles released 78 original compositions, but only five were written by Harrison. Opening the album with his observation about oppressive tax schemes was bold on an artistic and political levels — ninety percent of their earnings went to…the taxman.

The early takes of “Tomorrow Never Knows” show Lennon in a glum mood, with McCartney experimenting with tape loops (years before it became a de rigeur studio tactic). We are then quickly ushered into McCartney’s more upbeat efforts by bringing in the brass section for “Got to Get You Into My Life.” Various harmony arrangements are jettisoned, including some falsetto proffered by Harrison and Lennon. Eventually, Martin supplies horn arrangements, and we get to hear them highlighted in an instrumental mix. It is a direct link to the band’s initial desire to record at Memphis’ famous Stax Studio, and their deep appreciation of American soul music.

Harrison’s “Love You To” starts as a solo acoustic ballad, but then he picks up the sitar and completely changes the tone. He was given space for three compositions on Revolver, a massive jump from prior albums. Nearly everyone has acknowledged that Harrison’s efforts were subsumed back in the day, which is understandable in the face of the competition — McCartney and Lennon are generally regarded as the most successful songwriting duo in history. But with each successive album overhaul, Harrison’s star continued to rise.

The bevy of outtakes provides a glimpse of works in progress. “Paperback Writer” loops through several iterations, each anchored by Paul’s chiming lead guitar. “Rain” is heard in a galloping instrumental, but the expansive liner notes advise us that the version we’re accustomed to was slowed down for the master tape. Similar manipulation of tape speeds gave “I’m Only Sleeping” its ethereal sound, perplexing and endearing many listeners at the same time.

“Yellow Submarine” unfolds as a sad acoustic guitar folk song soon evolving into a knees-up ditty tailored for Starr’s limited (but improving) vocal ability. George Martin was in his element with the song’s sound effects, as he had cut his teeth previously doing comedy records and various avant-garde productions.

“Here There and Everywhere,” with its gorgeous stacked harmonies, is revealed as McCartney’s favorite of his songs. It was influenced by the the Beach Boys’ stunning Pet Sounds, which would in turn catalyze the Beatles’ landmark follow-up, Sgt. Pepper’s.

In the new package, Questlove provides an erudite essay, riffing on how he moved backwards into the Beatles catalog, mostly through hip-hop samples or R&B cover songs, like Aretha Franklin’s “Eleanor Rigby.” He does a great job of explaining why Ringo’s drumming consistently remains undervalued. He also points out the mutuality of interest about why soul artists are drawn to the Beatles: “It’s mutual. The early Beatles cut their teeth on Little Richard and Chuck Berry and Motown.”

Overall, the Revolver reissue is a worthy reassessment of a crucial and ground-breaking album — one that opened the door for several monumental LPs to follow, collectively cementing the Beatles as the most influential band ever.