This article originally appeared in the November 1992 issue of SPIN.

Cold, hard, professional and prepared, six felons head out on a diamond heist. Four return, one with a slug in his gut. The cops were waiting. Someone ratted. The cons suspect an inside job and slowly begin to rip each other apart.

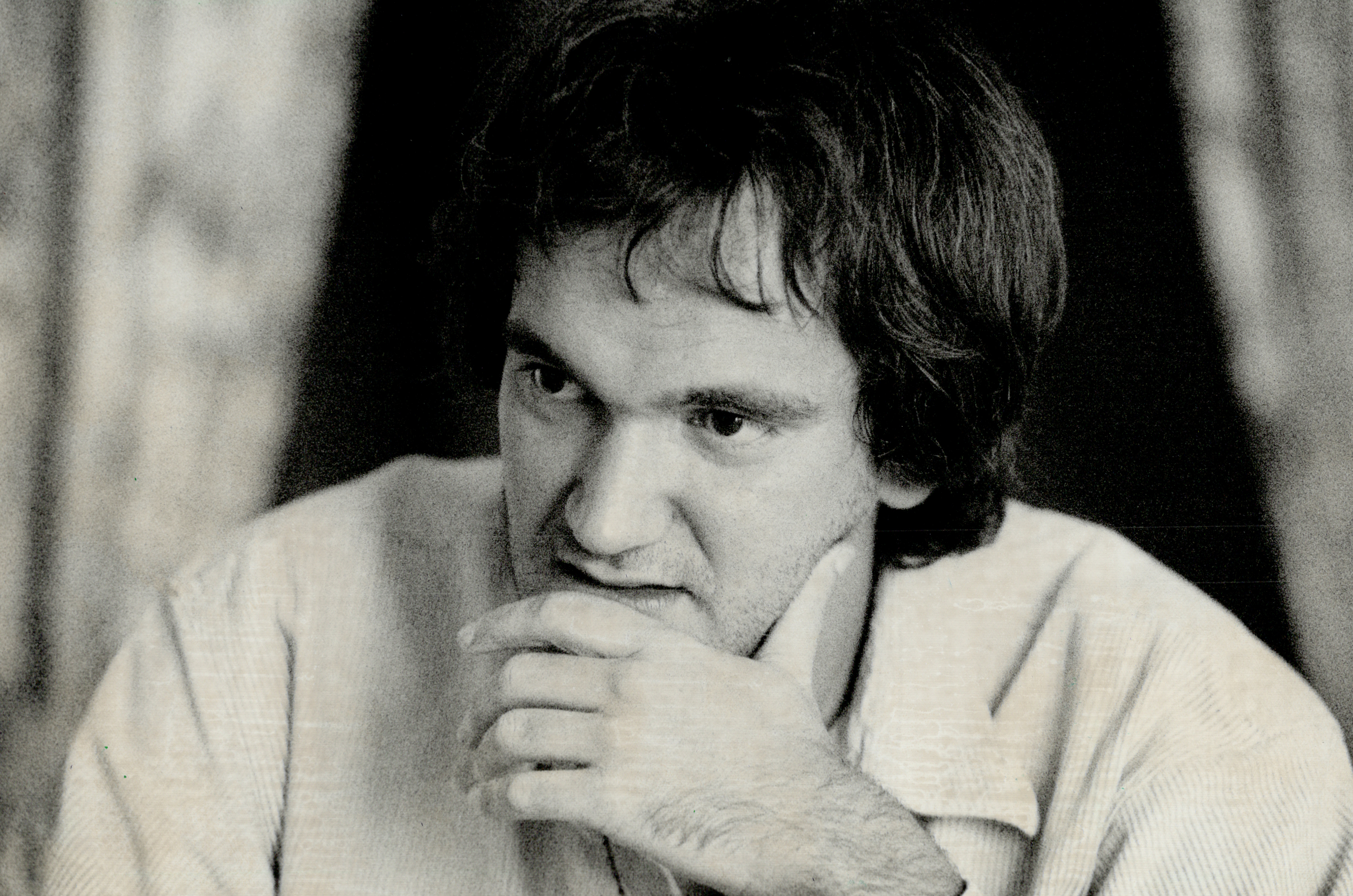

Quentin Tarantino‘s first feature, Reservoir Dogs, blends the writer-director-actor’s twin inspirations—American exploration movies and French art cinema—to produce a violent, stylized, and darkly funny exploration of underworld loyalties. The movie crisscrosses between the crime’s increasingly bloody aftermath and its perpetrator’s individual motivations and characteristics. The 29-year-old Tarantino toned his talent writing screenplays and working in a video store for five years before producing Dogs.

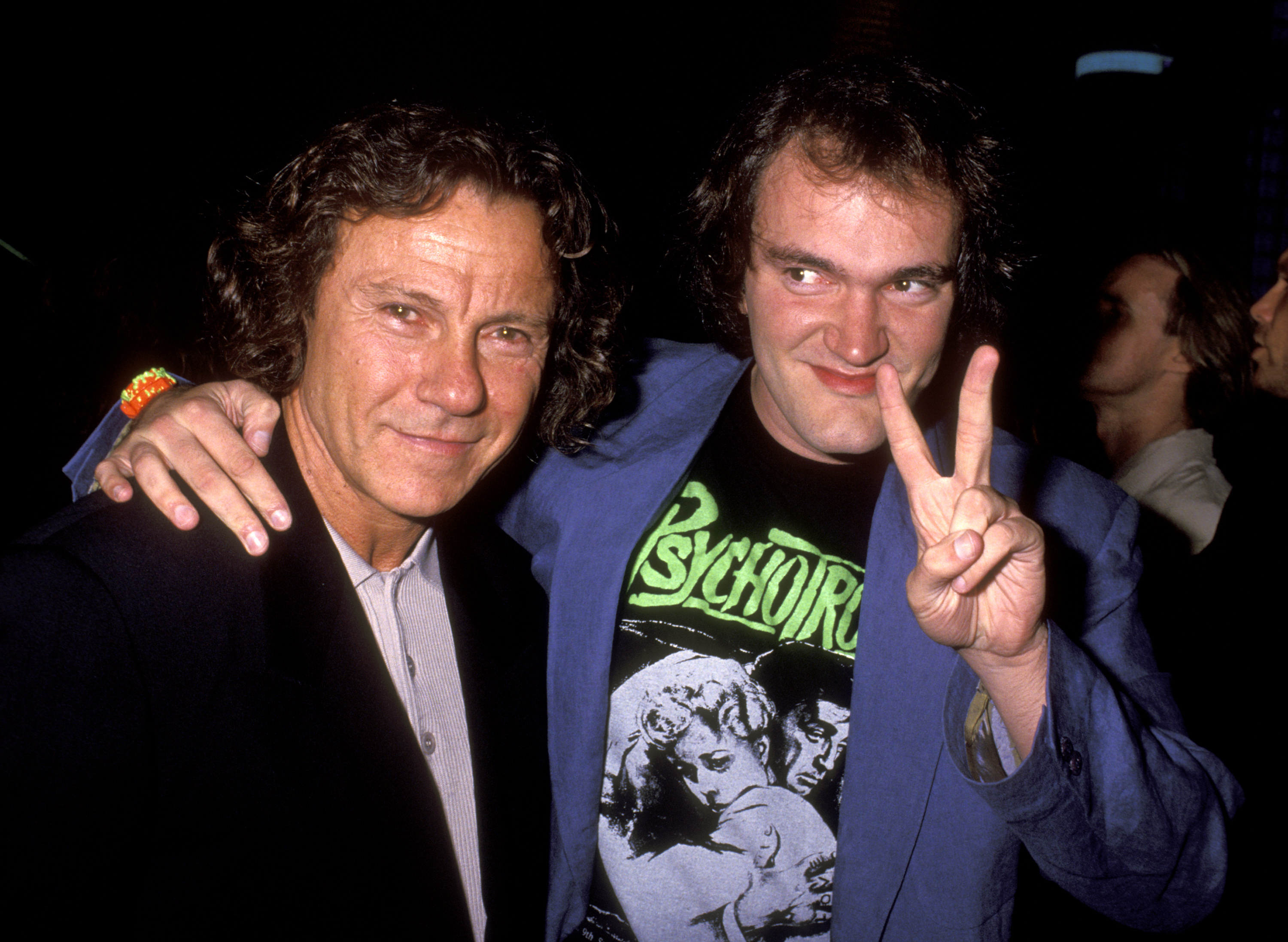

Originally intended as a dirt-cheap, 16-millimeter black-and-white exercise, the project received a boost when it attracted the attentions of Harvey Keitel and Roger Corman alumnus Monte Heilman (Two Lane Blacktop). With those men of weight signed on as coproducer-actor and executive producer, respectively, Tarantino’s screenplay gave off sufficient industry heat to induce an agent feeding-frenzy.

After auctioning platoons of male actors on both coasts, the director culled a fearsome selection to give life to his color-coded cast of cons. Keitel is the solid stickler for criminal etiquette, Mr. White. Britain’s hooligan dynamo Tim Roth gushes blood copiously as the wounded-in-duty Mr. Orange. Pop-eyed Steve Buschemi bristles with indignation as the outraged professional, Mr. Pink.

Also on hand: big Chris Penn; that irascible heap of flesh, Lawrence Tierney; and, in the movie’s showiest role, Michael Madsen. Madsen embodies the psychotic Mr. Blonde and ensures the film’s destiny as a future seat-filler via a scene in which he tortures a hapless officer of the law, all the while cutting a rug to Stealers Wheel’s ’70s one-hit wonder, “Stuck in the Middle With You.”

Commenting on his wrecking crew, Tarantino notes: “You have a collection of acting styles. You have Harvey, who is Method; Steve Buscemi, who comes from an underground theater background; Michael Madsen—a very naturalistic, unaffected, un-actor-y sort of actor. Lawrence Tierney has his Lawrence Tierney thing. You have all these personalities working together and that’s what creates the tension—and creates the fun about it.”

High-octane pulp though it is, the film’s several set-piece violent altercations are considerably more jarring than the beautiful choreographed carnage to which we’ve become accustomed.

“That’s what’s cool about it,” attests Tarantino. “The other stuff is action. It’s wild and crazy, it’s a cartoon. It’s nutty, and that’s fine. I’m not saying my violence is better, I’m just saying I want my violence to hurt. I want it to get under your skin. When Harvey’s kicking Steve around, that’s how fights are, they’re very ungraceful. They’re trying to fuck each other up. It’s not the hot things you see in movies, it’s very spastic. When you do it well and it’s effective, it’s disturbing. You get to people. They don’t like to be disturbed.”

The movie opens with a pre-felony roundtable discussion of, among other topics, the subtext of Madonna‘s “Like a Virgin.” The voluble Mr. Brown (played by Tarantino) claims that the catchy pop hit is a paean to deep and painful penetration.

The director is equally rigid in this conviction. “Someday I’m going to meet Madonna,” he says, “and she’s going to say, ‘That’s exactly what that song was about. You hit the nail on the head.’ I know I’m right about that. I know that’s what was going through her head.”