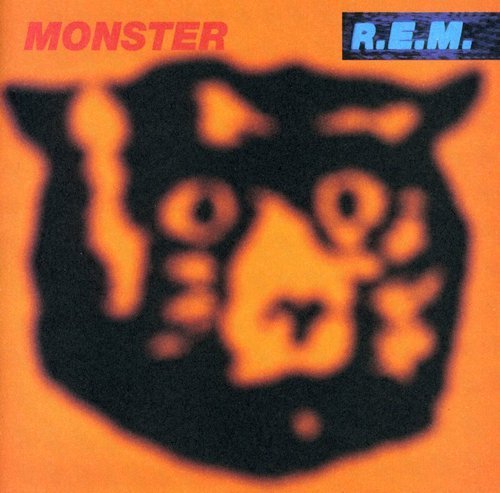

With Monster marking its 25th anniversary on September 27, 2019, we’re republishing our review. This piece originally ran in the November 1994 issue of SPIN.

Rating: Go directly to your record store. Buy this album. Immediately. Kill if you must.

In the beginning, R.E.M. brought forth “Radio Free Europe,” the airwaves were seized by a blurted code no one could quite crack, a call to arms and terms of surrender in the same asthmatic breath. The song held out asylum in place of utopia, ritual instead of desire. (Here, pilgrims bathed at a shrine consecrated to the memory of “Love Will Tear Us Apart,” and washed their wounds among the broken idols.) “Radio Free Europe” was an opening and a closing, first light and last rites: the muffled echo of unanswered prayers in the corridors of power.

With Monster, it’s as if R.E.M. has set out to dissolve not only the intervening years, but the weight of a world it helped shape as well. Noisy, jagged, as brutal as it is blissfully silly (“Circus Envy” indeed), this is its most implacable—and convincing—music since Murmur. As Michael Stipe’s voice shakes off layers of carefully applied self-importance, you can finally hear what the band’s impeccable surfaces had rendered mute: seething confusion, suppressed appetites, the cackle of unearthed skulls behind every loose-limbed chord.

RELATED: R.E.M. Announce Deluxe 25th Anniversary Reissue of Monster

But as with all of R.E.M.’s finest gestures, “I Don’t Sleep, I Dream,” “Let Me in,” and their ilk are intensely satisfying and impossibly ephemeral. The more deeply they draw you in, the further their essence recedes to a vanishing point of its own devising. Monster conjures a rough-trade beast (“Bang and Blame,” etc.), but beneath the leather and distortion, it’s still a shiny, happy one. (With R.E.M., the Alien always turns out to be their little exchange-student cousin E.T.) Peter Buck has temporarily shelved his trademark campfire-in-heaven rhythm strum, but his earthier attack is still rooted in a certain ancient decorum, an innate sobriety. Even as Monster flirts with unreason and breaks down old taboos, it observes the strict protocols of the forms it plays havoc with, bowing respectfully to what it undermines.

“What’s the Frequency, Kenneth?” lifts its catch phrase from the dadaist mugger who attacked Dan Rather a few years back. The song, wryly straddling the pop-irony curtain dividing Reservoir Dogs from stupid-pet MC David Letterman, revels in a nagging resonance that signifies nothing, but wants to say everything. Making nothingness feel like deliverance is R.E.M.’s genius and curse, the mystique Pavement gratefully sends up in “Power of the Picket Fence” and remakes in its own futile image on Crooked Rain, Crooked Rain.

For “Crush With Eyeliner,” R.E.M. goes out on a severed limb to invoke the mad, corrupt dazzle of Roxy Music’s “Street Life.” The incongruity of R.E.M. straying so far from hallowed ground is a stunning rush, yet the reversal of expectations produces no equivalent reversal of perspective. Beyond R.E.M.’s wish to throw away its accumulated maps and legends, to lose itself in adventure, the aura of sightseeing clings to every good move. Rock as guided tour through the bowels of its own amnesia: a city of discount artifacts, vendors hawking merchandise that proclaims, “I PASSED THROUGH THE BELLY OF THE BEAST AND ALL I GOT WAS THIS LOUSY T-SHIRT.”

Monster divides the last record’s brazen “Everybody Hurts” in two, as “Tongue” and the tremulous, pledging-my-soul “Strange Currencies.” Both are better than their tearjerking predecessor, but that’s almost beside the point—the shamelessness of “Everybody Hurts” is what struck a nerve, that naked need to have someone who understands (a Neil Diamond of our own). So while “Strange Currencies” is actually more subtle, even beautiful, it comes off as somehow more overwrought. Maybe a shade hysterical, too: passionate expressions rehearsed in a ceiling mirror.

Before R.E.M. could begin to lose its religion, it needed to invent one. Stipe draped himself in flinty empathy and a customized Turin shroud—a priest-with-no-name raising his flock’s naiveté from the dead, scattering hymns like incense. “Say a prayer at every station,” goes a mocking line in the new “King of Comedy,” but it’s too late to turn back. Not that the song, which sounds like it failed the audition for a U2/Zoo TV outtake, would if it could. “I’m not commodity,” Stipe sings with helpless sincerity. He can only mean instead of the impersonal, processed kind, R.E.M. represents the good, true commodity—organic, high in fiber, the communion wafer that melts in your mouth, not in your hand.

I’m reminded of that measured, sinister line from “Man on the Moon”: “Here’s a little ghost for the offering.” Holy ghosts and dead souls, moving from host to host, offered in tribute to a monster everyone likes to pretend is just imaginary. As long as “Bang and Blame” or “Let Me In” plays, insinuating themselves into every crevice of the moment or crawling out of a hole in your unconscious, it hardly seems to matter that the lumbering creature keeps eluding its supplicants. But there’s a name no one can utter, a face no one can look into: After the end of the world as we knew it, good old “Wendell Gee” grew up to be Forrest Gump.