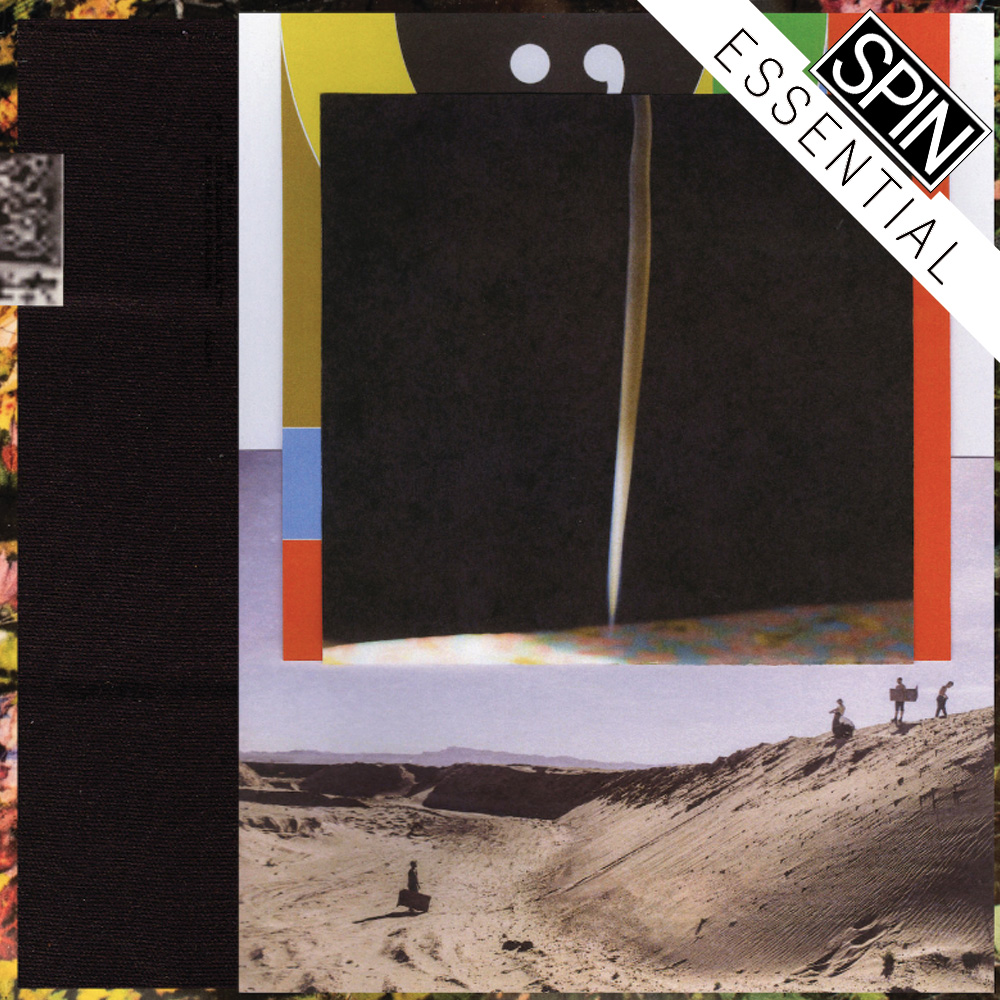

Bon Iver, the amorphous collective helmed by Justin Vernon, have only expanded over time. What began in the solitary quiet of a Midwestern hunting cabin has grown into something open and communal: the solo folk act becoming a real band, its shivering heartache giving way to warm, grandiose experimentalism. After the humble beginnings of For Emma, Forever Ago, the orchestral, optimistic Bon Iver felt like a radical statement of purpose. Then, thrown by the critical and commercial success of those two albums, Vernon pivoted toward the inscrutable on 22, A Million, with dense, electronic production and an accompanying visual language of codes and invented runes. To call it a retreat would be to misunderstand it—Bon Iver were, and are, still growing, integrating diverse collaborators and compositional structures for an ambitious but interior new sound.

On i,i, Bon Iver’s expanding universe feels at once new and familiar. The core band, whose members now include Wye Oak’s Jenn Wasner, is only the center of a much larger constellation of producers and instrumentalists. James Blake, Aaron Dessner, and Francis Starlite all find their moments on i,i, as do Young Thug producer Wheezy and longtime creative inspiration Bruce Hornsby. The string arrangements of Rob Moose make a welcome return, and Chris Messina, whose production was responsible for some of the most strikingly garbled moments on 22, A Million, remains indispensable. Vernon is still the dominant creative force, but on i,i, he steps confidently into the role of curator and conductor (an approach he may have adopted from his work with Kanye West).

The result of this collective energy is an album that’s both frank and easygoing, reveling in the magic of close personal relationships. This is made clear immediately by the 31-second intro, “Yi,” which pulls from one of Vernon’s early noise recordings with Trevor Hagen as Hrrrbek. Over lo-fi shuffling and stray feedback, the last gasps of 22, A Million escape into the ether—breathy, digital yelps that squirm and sputter before writhing out of existence. The first words on i,i aren’t lyrics, but studio banter: “Are you recording, Trevor?” “Yes!” Where 22, A Million opener “22 (OVER S∞∞N)” was a spare, anxious solo piece, i,i begins with Vernon’s best friend audibly in the room.

i,i begins in earnest with “iMi,” raw blasts of noise filtering into measured columns, lending the track its skeleton. “Living in a lonesome way / Had me looking other ways,” admits Vernon, the instrumental receding to accommodate his hushed delivery. The sonics are rhythmic and airy, underpinned by a beat that meticulously aligns string plucks and percussive claps. On the chorus, chantlike repetitions of the phrase “I am” emerge as some of the most sincere affirmations in a catalogue defined by sincerity and affirmation.

Though the album touches on the crises of spirituality that governed 22, A Million, i,i applies an almost devotional approach to the secular. On the sweetly intimate “Hey, Ma,” Vernon sings about a maternal figure “back and forth with light.” “Faith,” with its magisterial sheen, tracks both a broken personal relationship and a distance from the divine, never bothering to distinguish between the two. “Fold your hands into mine,” sings Vernon, closing out the bridge with a rare note of desperation. “I did my believing / Seeing every time.” On both songs, moments of sociality and connection feel sacred. “RABi” conjures a similar energy in delicate pastoral scenes: “There were six of us sitting creek side / Sifting fistfuls through the green / Every which way could be seen.” The God of i,i is the God of the personal, its power tangible and human.

“Sh’Diah” harkens back to the glittering ambient of “21 M◊◊N WATER,” hinting at a porousness between spiritual and secular, the self and others. Vernon’s falsetto is ecstatic: “Well, you find the time / Don’t you / For the Lord? / But you can find the time / Oh, can’t pass it around?” Lyrics give way to muddled whispers, and bleed into a stunning, 2-minute sax solo that seems to do what words can’t. Staring directly at the unnamable, it’s a near-perfect distillation of the album’s conceptual m.o., and one of the prettiest songs Bon Iver have ever recorded.

Even in its title (which at first scans as some kind of Bible reference, but is really just short for “Shittiest Day in American History”), the song finds profundity in the profane. “Holyfields,” too, dusky and sublime, scans as both a reference to Elysium and Evander. How many of Vernon’s koans are really just about his love for the Packers? Or about good weed? Vernon says the word “toke” more than once on this album and still manages to eschew self-parody. Collapsing the space between the silly and the sacred, Bon Iver bring levity to what might otherwise be staid and overwrought.

Like many of the tracks on i,i, “Sh’Diah” was first performed with Minnesota’s TU Dance as part of an interdisciplinary concert series called “Come Through.” Designed with original choreography in mind, the album is spacious and welcoming. In lyric videos for songs like “We,” “Naeem,” and “Jelmore,” dancers inject a refreshing physicality into the band’s typically obscure, cartoonish visual grammar. Vernon’s expansive ethos extends to both sound and space, with free-associative movement as a governing principle. There’s nothing here that you couldn’t dance to, if you really wanted to. Vernon calls “We” a “fucking banger” in the album’s Apple Music description, and even the stripped-back “Marion” has its own somnambulant choreography. The physical component only deepens the album’s collaborative, humanistic spirit.

Renewed by that physicality, and by the strength of the collective, Bon Iver remain dead-set on evolution. As the band has grown, so too has Vernon’s philosophical outlook. “So what of this release,” asks Vernon on the closer. “Some life feels good now, don’t it?” It’s less a question than a declaration—prismatic and free, i,i arrives, simply, at contentment.