At the end of the title track of 2013’s Monomania, the record’s protagonist—presumably a thinly wigged Bradford Cox—speeds off down the highway on a buzzy little motorbike. On that album, one about its bandleader’s unshakeable compulsion to produce artwork, the act of leaving the scene was itself a work of art. Cox, the whirlwind of inexhaustible musical output and Web Content that sits at the center of the band Deerhunter, must create. His very breathing tends to carry a poet’s burden; no personnel change, shift in audience preference, or simple pratfall will disrupt his output. To wit, Monomania was a transition period for the band, with a new lineup taking shape as bassist Josh Fauver (up to that point the low-end ballast of every Deerhunter record) departed the group with no explanation—no explanation to the public, nor, reportedly, to the band. Josh McKay, the band’s bassist on Monomania and every subsequent recording, including Deerhunter’s latest, the bewitching Why Hasn’t Everything Already Disappeared?, stepped into Fauver’s shadow.

And while the record before us now features McKay’s solid playing, it is the Fauver era that strikes the most resonant chord at this moment, after his shocking death late last year. Revisit this live video of Deerhunter at Pitchfork Music Festival in 2011. Hand Bradford one of the tightest cuts the band’s ever written, “Nothing Ever Happened,” a short-but-sweet number that leads to one of the most-inspiring guitar riffs in modern indie rock history, and watch him stretch out its relentless bass-and-drum groove into more than 10 minutes of stream-of-consciousness motorik. It’s only near the end of this 12-minute rendition that we get a glimpse of the united spiritual conduit of this iteration of the band—a group so cohesive and telepathic in their practice that even intense summer heat can’t put a hiccup in this physically exhausting song from the 2008 Deerhunter LP Microcastle.

I just watched this clip for the first time since Fauver passed away in November 2018 at the far-too-early age of 39 (for reasons undisclosed)—and it made me weep. Not only did he co-write this song, one of the most moving pieces of music I’ve ever known, he was somehow the second Deerhunter bass player to die an untimely death. A skateboard accident claimed the life of Justin Bosworth, the band’s original bassist. How do we square these two uncanny passings with “He Would Have Laughed,” the band’s painterly tribute to the late, great Jay Reatard and the final song on the final album on which Fauver played, 2010’s flawless Halcyon Digest? Observe Fauver’s calm remove, a cigarette dangling from his lip for nearly the entire song, a song that puts him center stage. Now remind yourself this immense talent is lost. This has already disappeared. And all this is the stuff rock ’n’ roll legends are made of—because what truth could I relay to you that edges anywhere close to the truth of Fauver’s family, or the truth of his importance within this band? We will never know.

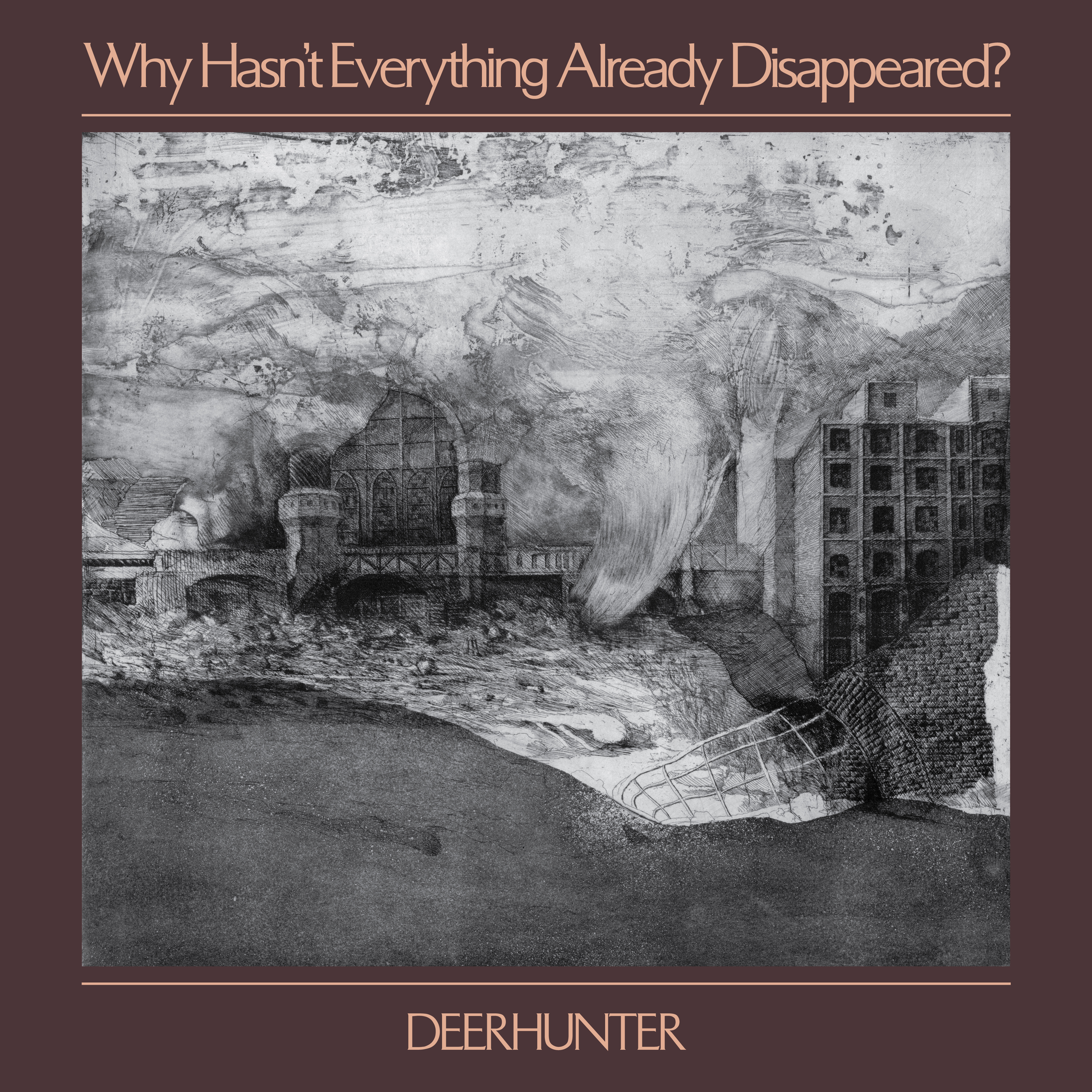

This huge loss will forever color the release of this LP for Deerhunter. Why Hasn’t Everything Already Disappeared? sits removed from the timeline of Deerhunter the people, and strictly adheres to the timeline of Deerhunter the band. Which is both tragic and fitting, because this album does not actually concern itself with the fundamental human inquiry, “Why?” Instead, the 8th LP from the nebulous Georgia-based group ignores the cultural urgency of explaining every single moment, and refocuses onto experiencing every moment. It’s a fundamental difference that discards epistemological concerns for ontological ones—modes of being supplant modes of knowing.

Because, what does Bradford Cox have left to explain? What more can we know? This person has given us so much over the 17-odd years Deerhunter has been making music. In fact, in what appears to be a favor to music journalists everywhere, he’s provided one-or-two sentence descriptions of the inspirations behind each song on the album—a courteous first. (I recall a 2013 press conference where Bradford wouldn’t answer a question about the song title “T.H.M.” Years later, I figure it might be “The Hidden Meaning.”) Topics on the new record include the Soviet Revolution, gothic architecture, a “eulogy for emotions” (“What Happens to People”), the very-present dangers of nationalism, the toxicity of nostalgia, the ruin of the environment, beams of information from both “the slipstream” and “the afterlife,” and James Dean, who spent the summer of 1955 in Marfa, Texas, working on his final project Giant, before dying in September of that year.

A chunk of Why Hasn’t Everything Already Disappeared? was recorded in Marfa, as well as elsewhere in Texas. The fascinating Welsh singer Cate Le Bon receives the lead producer credit, alongside Ben Etter and Ben H. Allen. The production has the unmistakable feel of Allen across it, in instrumentation unique not just to this album, but to a larger trend toward Baroque-era sounds. Harpsichords (played by Le Bon), various mallets, horns, all sorts of guitars, and strings from violins down to contrabass all make appearances. Tim Presley—late of The Nerve Agents and who performs with Le Bon in the band Drinks, as well as his own project White Fence—scores an “abstract lead guitar” credit on “Futurism.”

What’s fascinating about Why Hasn’t Everything Already Disappeared? happens to be how the sound of the record matches its philosophy, in that the Baroque instrumentation, here, also leads one to contemplate Baroque performance—this is a record that sounds like it could be performed in living rooms, in department store foyers, on mall stages, at any moment, anywhere. The songwriting stands strong enough that the context of the music matters less and less, and the instrumentation becomes secondary to the tonal and lyrical moves—chamber music for the microdosing set.

Still, the album captivates, a blend of tools from the Old World, the New World, and a Future World alike. A Gary Numan-esque Moog riff drives the instrumental “Greenpoint Gothic,” before a marimba pans in the stereo, recalling the undersold Aloha LP Some Echos. Bradford’s voice sits central in the mix, his sensory-loaded lyrics acting as the Virgil to the listener’s Dante—except we’re already in hell. It isn’t Bradford’s mission to reframe the world as explicitly “bad,” but to transmute the immense mantle of human consciousness into something palatable. He and Deerhunter succeed in spades. And it isn’t a sad tenor, nor is it a hopeful one. This is just the way it is.

More generally, this might be Deerhunter’s cleanest record, in not only production, but also arrangement. The lyrics to the ponderous basso continuo of “Element” stand strong on their own—as do many of the boffo lines across the LP. “They said he was gone / Never coming home,” Bradford divulges, in unassuming couplets. It’s when he hits the repeat of, “I’m gone, I’m gone, I’m gone, I’m gone,” that the bones shake. “Cancer was laid out in lines / The road was wide / The road was silent,” he sings. Because all we can really do is move forward, driving ahead, loading up our buzzy little motorbike and hitting the pavement. Because “why hasn’t everything already disappeared?” is not just the question a tired existentialist asks at the sundown of an empire. It’s also an expression of exhaustion, of knowing one’s remove from the machinations of a world around them, of the resignation permeating every interaction—except our interactions with the self, if we so choose.

Because we can never know the whole truth of Bradford, of Fauver, of Moses or Lockett or McKay or anyone else in this band or anywhere. What’s fantastic about Deerhunter is that legendary aspect, where the antiheroes, the most unlikely heroes, become the sigil for our most insecure aspects, the moments that shake us to our core. It’s not self-mythologization when the facets ring so true. I’m not sure why everything hasn’t yet disappeared. But I do know what will disappear, without a doubt: our loved ones, the actual people we hold close. Treasure not the impossible task of fully understanding. Treasure the tiny little miracle that some benevolence allows us to hear a record like this and know we’re not alone—even if we appear to be.