I should probably take Conor Oberst out for a sandwich because it looks like he hasn’t had one for a while, but instead I buy him a beer. And then another. We’re at a quiet bar in Manhattan’s East Village, not far from our meet-up spot, the dog run in Tompkins Square Park. “These dogs are crazy,” says Oberst, perhaps alluding to the cosmic predicament of the city’s cooped-up, backyard-deprived bowsers.

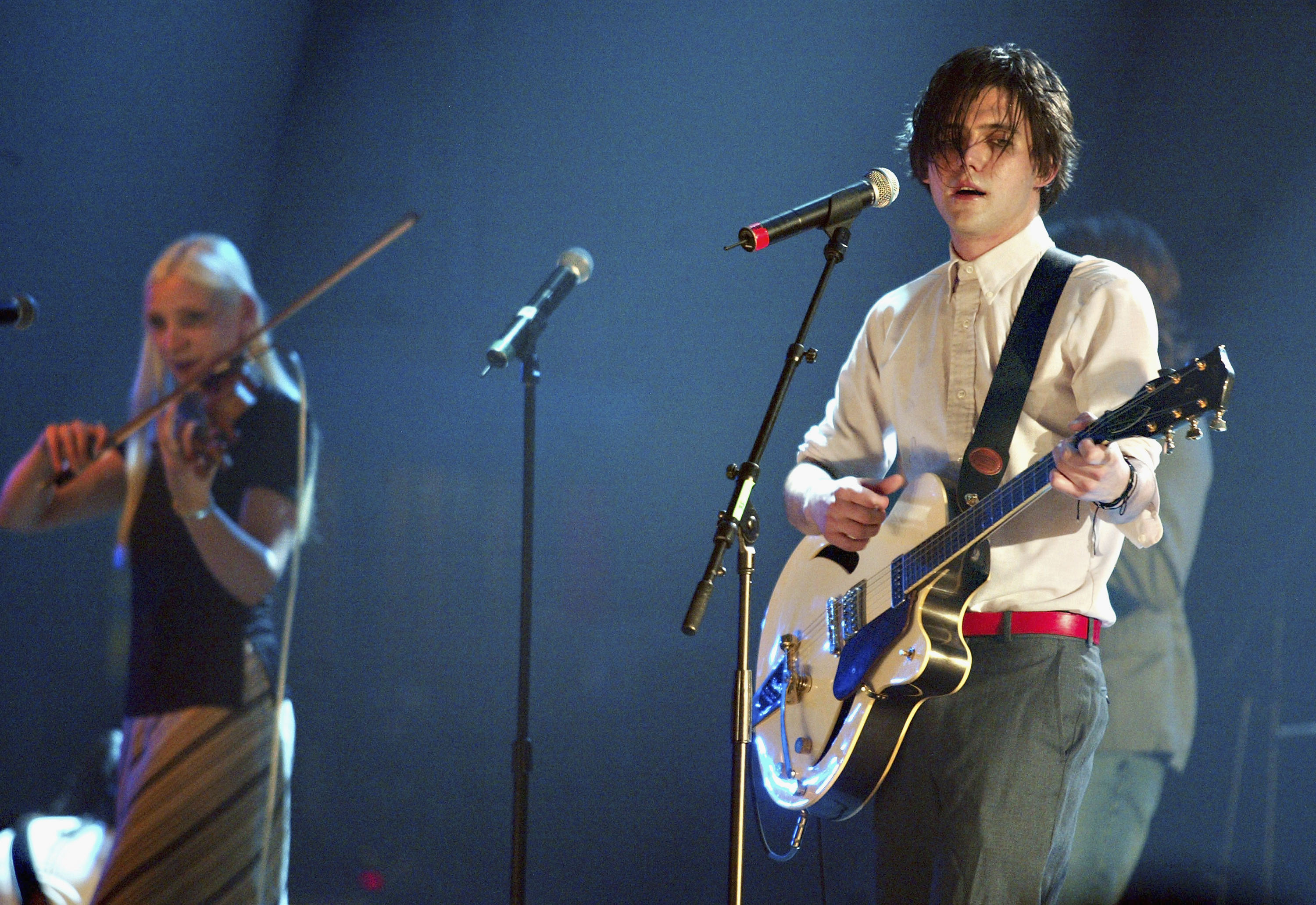

The 25-year-old singer/songwriter has lived in this neighborhood for almost two years, but a Midwesterner never gets over New York’s random unnaturalness — even if this Nebraskan’s ivory pallor and Oliver Twist indie-punk garb fit in perfectly with his adopted environs. Going on Oberst’s waifish myth, I feared the diminutive leader of Bright Eyes might be less than forthcoming. But it’s not so much that he hides behind his shock of black hair as he just doesn’t cut it. And while he lacks that look-you-in-the-eye, car-salesman’s handshake that so many Midwestern dads impart to their offspring, he seems much more inclined to carefully engage than timidly recede.

He’s gracious, even folksy, touched by a bit of the wide-eyed Tom Sawyer vibe that Bob Dylan has retroactively constructed for his teenage self in his book Chronicles, Volume One. But unlike chameleon Bob, young Conor only paints in varying shades of white-knuckled sincerity, which would be fine if his ravenous cult didn’t seem hell-bent on elevating him into the role of pop prophet.

In late 2004, Bright Eyes scored the No. 1 and 2 top-selling singles in America — “Lua,” from the new folk-rock record I’m Wide Awake, It’s Morning, and “Take It Easy (Love Nothing),” from the simultaneously released techno-pop Digital Ash in a Digital Urn — a testament to the apostle intensity of Oberst’s audience and a remarkable achievement for an indie artist. He’s not on MTV (yet), but the girls at this shows lose their minds like he’s bigger than Usher, even on the nights when all he does to return their affection is sip merlot and talk to his shoes. They’re not imagining things. When Oberst curls up feline-like on a couch in the back of the bar or affixes me with a tractor-beam, opal-eyed gaze, he’s as much Madonna as Dylan, except with only a shred of their image-manipulating self-awareness.

This potential star power could be pretty exciting for him, but it’s also a little troubling. No matter how successful he may get, the self-lacerating sword of white-hot authenticity is still the only weapon Conor Oberst knows how to wield.

SPIN: I’m Wide Awake, It’s Morning is similar to other records you’ve done, but Digital Ash is a big departure. Why did you decide to do something more electronic?

Oberst: I wanted to make a record that was based around the rhythms. It seemed like up until now most of Bright Eyes’ music had been melody and atmosphere, more “in your head” music, but not a lot of bodily response. And I was interested in trying to achieve something where your foot’s tapping and your head is nodding right off the bat, even before you care what’s being sung. That’s how we got into those longer outros. If we got into a groove where it felt really good, we’d kinda go with it and let it play itself out.

It seems like I’m Wide Awake, It’s Morning is more personal and Digital Ash is more universal. Did the different musical settings allow you to approach the lyrics differently?

I think Digital Ash is about the fear of death. I feel like with the Internet there’s the idea that you can have all the world’s information — every piece of art, every library, every blueprint, everything. Its essence exists, but it doesn’t have any substance. It’s not like this [touches the table in front of him]. I don’t understand mainframes and shit like that very well, but it’s not tangible and I find that amazing. I see that in the context of our bodies and love and music and souls or whatever. There’s energy that’s very real but has no physical form, and I like to think about that. These things are gonna fall apart — these things that we walk around in — and I don’t really know what I think about the afterlife, but I do think that things can continue beyond their physical being.

The line “I’m wide awake, it’s morning” comes at the end of the record. You seem to be saying that you have to get to the absolute bottom before you can see any light.

I guess the main idea for the song and [album title] was that you’ve gone through this supposedly long night and the sun’s up, but it’s not necessarily hopeful, like everything’s gonna be okay now. It’s more like, it’s gonna be a crazy busy day, and it’s a rallying call to get your head on straight; pay attention, you’re gonna have to focus because everything’s gonna happen really fast and you’re gonna have to be on point.

What do you wanna focus on?

I never wanna succumb to apathy again. I don’t wanna succumb to fear — to any of these pressures that are imposing themselves on me — either personally or in regards to the music world. Those are my things that I go through. But in general, we all have our struggles and things that weigh on us. Fear and anxieties and hopes and dreams, and you have to just get your oars in the water, ya know, carry on. Tuck and roll. And make the best of your time, however you see fit. For me, making art, finding clarity through words, and loving people and being good to people and helping people when I can — those are things worth devoting yourself to.

Did you write most of the music before the 2004 presidential campaign heated up?

We recorded the folk record in early February 2004. Everything was written in 2002 and 2003. Basically, ever since the 2000 election, electoral politics — something I really didn’t think about before — marched right into my room and woke me up at night and was constantly broadcast into my senses. The conditions here and all around the world worsen each day, and I have no choice than to be affected by it. Usually when that happens, I have no course but to try to write about it or try to understand it through some creative process.

There must have been a lot of optimism when you played the pro-Kerry Vote for Change Tour. Did you think Kerry was going to win in November?

Yeah, I had a sense all the way up until Ohio fell that Kerry was gonna win. The day of the election I was in such a great mood.

Where did you watch the election results?

We started at this MoveOn party [in Manhattan]. My friend got sick, and that was the first sign that something weird was in the air. Then we were at an apartment and wanted to go out, but we couldn’t get away from the TV. Then after [Bush won] Florida, we went to a bar. We were like. “This is starting to feel weird.” And then once I realized that it was out of my hands, I just fuckin’ ordered a real big whiskey, and when I was, like, super drunk I called Steve Earle [laughs]. I didn’t get a hold of him. I don’t even know what I would’ve said. Just some desperate plea.

What was it like playing in front of such huge audiences on the Vote for Change Tour?

It was a learning experience. We’ve played similar-sized things, but it’s a lot different when it’s outside in a festival atmosphere. The first night I was horribly nervous, but it made me feel good playing with Bruce [Springsteen] and R.E.M. and these legends — huge names in my music history. But after a couple shows, I realized that it’s only as weird as you wanna make it. At the end of the day, they’re still doing the same thing that all my friends in bands are doing. They write a song and they get up and they sing it to people. My parents were huge Springsteen fans, and he was one of those voices that I grew up hearing. At some point I just went back and rediscovered the records. He’s really an amazing. sweet person, and he went out of his way to make us feel like it was gonna be okay. The first night he came to our dressing room and was like [adopts gruff voice], “You’re gonna be fine.” And he came back afterwards and said it went great. He called after the election, too. I was still pretty down in the dumps, and he was just like, “It’s not over. This is just the start.”

Do you believe that?

I do. On good days I totally believe it, on bad days I can despair for a little while. But I think the really beautiful thing about America is its ability to reform itself and become better. It’s done that throughout its history, and right now we’re at this real strange time, and I think inevitably the pendulum will swing back.

On the electronic record you sing about “the sorrowful Midwest.” In 2003, you moved to New York from Omaha. How has your perspective on the Midwest changed since then?

Well, I’m kinda split down the middle. On one hand, it would be too frustrating for me to live in a place where I’m politically in the minority and feel so out of touch with the mainstream, which is the case in Nebraska. Being in New York, I feel a lot more at peace — just kinda like safety in numbers. Most people here feel similarly, and that makes it easier on a day-to-day basis. But at the same time, I am from the Midwest, and I feel very like that shaped me. And the people in Middle America deserve more credit than they get at times. They’re not simple people, and they’re capable of thinking outside the lines that are drawn for them. Basically, the Bush administration has managed to pull the wool over everyone’s eyes through the vehicles of fear and this war on terrorism and war on Iraq and all this pseudo-nationalism and aggressive psychological campaign on America. And it’s worked. But they aren’t serving those people. Bush’s policies are horrible for average Americans. He’s not helping Joe Six-Pack in Omaha, I can tell you that.

You had two singles — “Lua” and “Take It Easy (Love Nothing)” — debut at No. 1 and 2 on the Billboard Singles Sales chart. Do you feel like a pop artist or that you have any relationship to the world of pop?

I can’t consider it, because it has nothing to do with me. It’s not something you can control. Public image is a very strange thing to me. It’s not you at all. People get lost and believe their own myth and get into this really dangerous place where they’re doing everything they can to see the reflection and living on people’s response to their actions and their songs. To me, that would be a really bad place to be in. So I’m forced to ignore it. I mean, with the Billboard thing, I thought it was rad just because, apart from it being my band, it’s cool that an indie label [Saddle Creek] can outsell all these labels that have way bigger budgets. It’s a triumph for this idea that there are music fans and that you don’t have to be played on the radio or on MTV.

Your fans are obviously very intense about your music. Do you wish you could get more control over your image and how people perceive your music?

I’ve thought about that. I think about people like Dylan and David Bowie, who’ve managed to re-create themselves so many times, and I think they’ve gone to that next level and they’ve realized they have to live with this other thing — this evil twin, this person who’s you but not you. So they make the most of it. They actually use it to their advantage. They twist it to the point where it’s, I dunno, artistic, and to me that’s really exciting. It’s like, “Hey, if you’re gonna project all your own bullshit onto me, I might just turn around and fuck with you.” I think that’s cool.

Do you think that might make playing live a little easier?

With performing, I haven’t really mastered that yet, and I figure that the best I can do and the most honest thing I can do for the fans is to behave how I feel like behaving that day. Not in the sense that I plan it out, but if I feel like being quiet and reserved and not talking between songs, just playing my shit and leaving, I’ll do that. If I feel like telling jokes and making small talk with the audience, then I’ll do that. It’s a conversation. I mean, I’m not much of a “showman,” ya know. Maybe sometime I will be.

You pretty much always sing in the first person. Have you ever considered writing a song that didn’t use the word “I”?

I’ve tried. And it’s hard. It doesn’t matter if I’m trying to imagine being an old man or a girl. You can’t help but think people are gonna hear it as you. I have taken lines out of songs because I thought people might assume it’s about them — and I liked the liens. But it doesn’t seem worth it.

What protest is “Old Soul Song (For the New World Order)” based on?

The Iraq protest. It was my birthday: February 15, 2003. It was the last big protest before the war started. It was amazing because you felt very empowered and sort of hopeless at the same time. It’s strange how that works.

That combination of possibility and hopelessness seems to be a theme on the two records.

I don’t think the albums go far enough to answer that. I’ve thought a lot about it lately. Where do I go from here? It’s hard. I don’t want politics to consume my whole life. I don’t write love songs, or whatever kind of songs. To me, I’m just a songwriter. I just wanna write about every aspect of life if I can, however simple or complex or subtle. Right now what’s going on in the world is just on my mind a lot. Maybe it won’t always have to be on my mind as much. That’d be nice.