When Pearl Jam’s Ten came out a decade ago on August 27, 1991, pretty much nobody cared. Unlike Nirvana’s Nevermind, which a month later revolutionized music faster than Kurt Cobain could pull the hair from his eyes, Ten took a full year to climb the charts. “Jeremy,” the third single and the band’s only true video, finally unleashed the floodgates in the summer of ’92.

Yet even then we had little sense what Pearl Jam represented. A few million MTV fans and some historic live shows notwithstanding, they hadn’t fully arrived. Their throbbing, baritone sound was branded by some as a sellout, corporate version of grunge, and the band members themselves couldn’t shake the feeling that, where it counted, they hadn’t registered. Especially their lead singer–an outwardly shy but manically competitive surfer from San Diego who’d been plagued with identity questions long before anyone started debating the meaning of “alternative.”

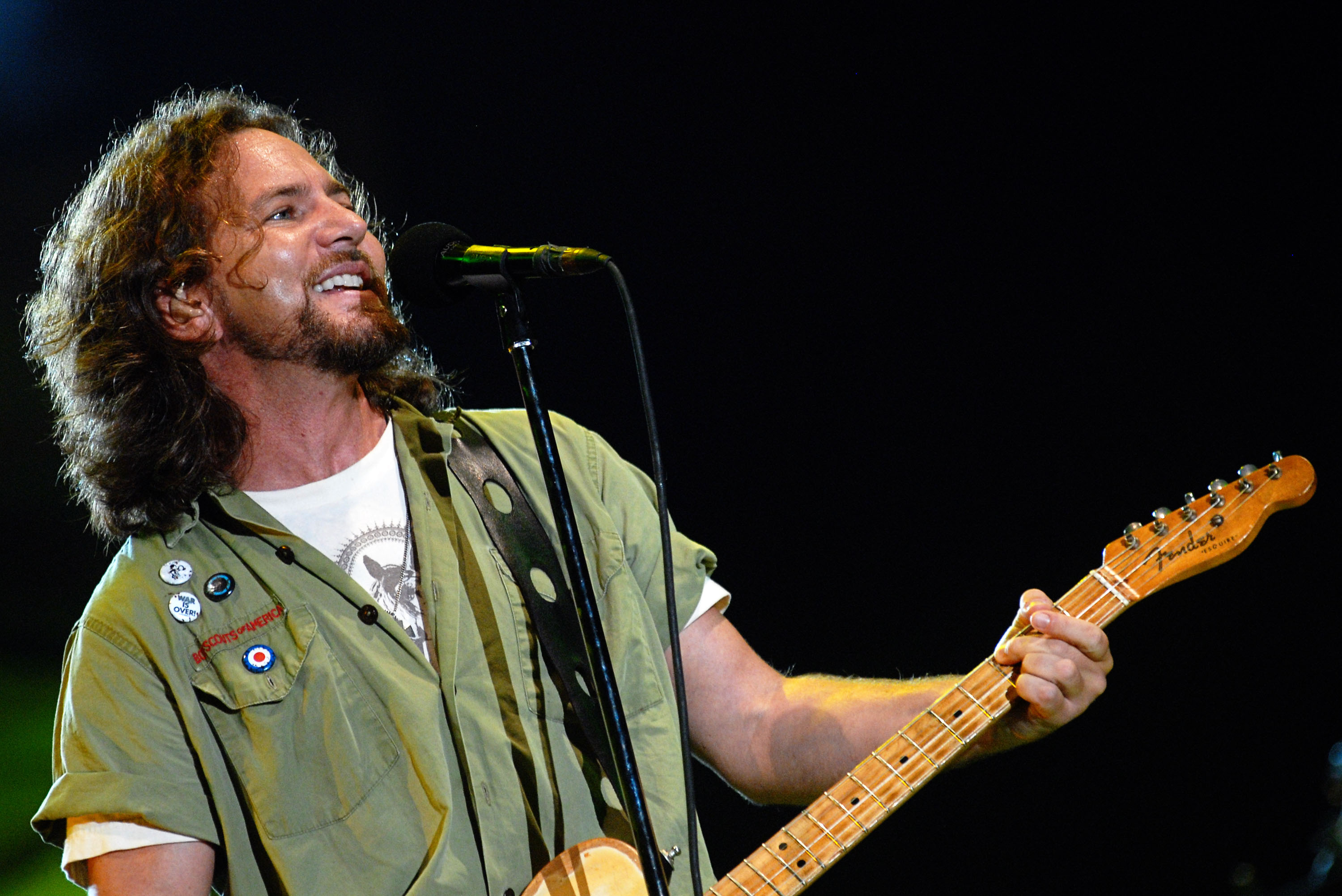

Eddie Vedder grew up with a man he thought was his father and wasn’t; when he found out, he became what film director Cameron Crowe calls “a living Pete Townshend character,” consumed with unresolved hurt. But that isn’t the Pearl Jam story–nor is lead guitarist Mike McReady’s days in the juvenile hair metal band Shadow, nor is bassist Jeff Ament and guitarist Stone Gossard’s formative experiences in the pivotal Seattle indie-rock band Green River, which would also beget Mudhoney. Ament and Gossard left Green River to pursue mainstream rock glory in Mother Love Bone, then saw it ripped away when lead singer Andy Wood died of a heroin overdose right before their debut’s release in 1990.

It’s the combination that sets up the Pearl Jam story. The vocals that Vedder added to the instrumental demos he got through his friend Jack Irons (later one of the band’s ever-revolving cast of drummers) resonated precisely with Gossard and Ament’s sense of loss. A trip to Seattle to check the fit, and the result was a band that exploded both live and commercially before anyone had had a chance to figure out what the goals were. And then a tumultuous decade, marked by inter-band squabbles, contentious back-and-forths with the pop machinery, and, long after every question seemed to have been settled, a tragic concert at which nine fans died.

The group that was once accused of being synthetic grunge now seem as organic and principled a rock band as exists, continually tweaking the industry: introducing what became their biggest single (“Last Kiss”) as a fan-club-only release; producing 72 live albums to document their 2000 tour. We talked with the band and their contemporaries–musicians, crew members, friends, and industry folks. Mixed in with some great stories is the answer to a paramount question: Why were Pearl Jam, virtually alone among their peers, the ones who kept the flame alive?

1990: Prehistory

SEPTEMBER: In San Diego, Eddie Vedder adds vocals to demo tapes of a nascent Seattle band, creating the first Pearl Jam recordings. OCTOBER: Vedder travels to Seattle to rehearse with the band. OCTOBER 22: The band play their first show at the Off Ramp.

EDDIE VEDDER: I always had the kind of clip-on-tie, stocking-the-shelves-at-drugstores jobs. And for that first week of rehearsing with the band, I wasn’t going to have to go to work. It was just going to be about music. We practiced in an art gallery, in the basement. And the alley that we were on was like crack-alley central. I remember having to use the restroom upstairs and going through these rooms that smelled of oil paint and sawdust and stuff. The guys would come in, and we’d practice and then maybe go play some pool and then come back and keep working, surrounded by Gatorade bottles with piss in them for those times when you didn’t feel like walking up the stairs.

KELLY CURTIS: Eddie was this shy guy. It was just the opposite of [Mother Love Bone frontman] Andy Wood, who was this flamboyant, David Lee Roth kind of guy.

JEFF AMENT: The minute we started rehearsing, and Ed started singing–which was within an hour of him landing in Seattle–was the first time I was like, “Wow, this is a band that I’d play at home on my stereo.” What he was writing about was the space Stone and I were in. We’d just lost one of our friends to a dark and evil addiction, and he was putting that feeling to words. I saw him as a brother. That’s what pulled me back in [to making music]. It’s like when you read a book and there’s something describing something you’ve felt all your life.

STONE GOSSARD: I don’t think I appreciated Eddie like I do now back then–his words and where he was coming from. Writing songs like “Release” of “Even Flow” in that basement together, I knew immediately when he was singing it felt good. But it took Ed and me a long time to get to know each other. We were very different kinds of people.

MIKE MCCREADY: I’d never been in a situation where it clicks. It all happened in seven days. It was very punk rock. Eddie would stay there in the rehearsal studio, writing all night. We’d show up and there was another song. And then he had to get back home to work. I remember giving him a ride at about five in the morning, to Sea-Tac Airport. I remember him saying, “Don’t be late!”

MICHAEL GOLDSTONE: This little experiment ended up turning into Ten within a six-week process. Ed went up to Seattle initially, came home, moved up there, and never came back.

CAMERON CROWE: I love Mother Love Bone, so when I was writing the movie that would end up being [1992’s] Singles, I wanted to interview Jeff and Stone to explore the whole coffee-culture, “two or three jobs, one of which is your band” lifestyle. The terrible turn of events that took place was that Andy died. And everybody just instinctively showed up at Kelly [Curtis]’s house that night. For me it was the first real feeling of what it was like to have a hometown–everybody pulling together for some people they really loved. That was a pivotal moment, I think, for a lot of people there. It made me want to do Singles as a love letter to the community that I was really moved by.

Few people know this, but Stone is actually in [Crowe’s 1989 film] Say Anything… He plays a cab driver, and Ione Skye looks at him and kind of flirts with him a little bit as they’re stuck in traffic on her way to graduation.

AMENT: I definitely don’t talk like Matt Dillon. But I made a couple of thousand bucks loaning him my clothes.

MCCREADY: I really liked Stevie Ray Vaughn, so hey–I tried to look like him. At least I had gotten out of my mullet phase. Eddie just had his punk rock thing. He wore what he wore and still does. [Jeff and Stone] dressed a certain way, because that was their clique–that sarcastic, playing-like-you’re-at-an-arena-to-30-people look.

GOSSARD: For a long period of time, me and Jeff would have loved to be in Get Your Wings-era Aerosmith, or Iggy Pop, or David Bowie. But there was something going on in Seattle that added a different element, a kind of garage approach.

CROWE: Eddie was painfully shy. It was weird because he was… barely there. But you couldn’t take your eyes off him. There’s a guy sort of sitting across from you, with his hands on his lap, and looking down, and you wanted to reach out and let him know that he didn’t have to be so shy. He was and still is an amazing listener. When he locks in and he’s talking about something that matters to him, the whole world disappears. Hours can go by. The first time I met him, we mostly talked about Pete Townsend. He knew every detail. I remember very clearly my feeling that Pete Townshend could written this guy as a character. He was a living Pete Townshend character.

SUSAN SILVER: They played their first show at the Off Ramp, a female-motorcyclist bar. It was the same club Cameron shot Soundgarden in for Singles. And everyone was nervous, wanting to see the phoenix rise. There was such an intense connection among all of them.Even though the Off Ramp show was amazing, and people wanted to see Stone and Jeff win, when they opened for Alice in Chains [on December 22] at the Moore Theatre, there was still a lot of grieving about Andy. He was such a special guy, such a character, so fearless and outrageous–the whiteface and the sparkly spandex outfits. So this was the first time that a lot of fans saw Eddie, and the feeling I was picking up from the audience was “Who is this guy? Is he good enough to fill Andy’s shoes?” It felt like the place wholeheartedly accepted him.

CROWE: At the Moore Theatre, the first song they did was “Release,” and I remember looking over at Nancy [Wilson, Crowe’s wife], and we were like, “That’s the shy guy? Oh my God!” Soon he was hanging from the rafters. It was sort of like the end of Eddie as the excruciatingly shy guy.

1991: Given to fly

MAY 25: Drummer Dave Krusen fired. AUGUST 2: “Alive” single is released. AUGUST 23: Drummer Dave Abbruzzese plays first show with band. AUGUST 27: Ten is released. OCTOBER-DECEMBER: Tour with Red Hot Chili Peppers, Smashing Pumpkins, and Nirvana.

CHRIS CORNELL: Stone and Jeff were in Green River, and Green River and Soundgarden always had a friendly rivalry. I’ve had discussions with Johnny Ramone about the New York scene when the Ramones were coming up, and he was very surprised at how well bands like Soundgarden and Pearl Jam would get along, because he said that in the New York scene, bands weren’t very nice to each other.

NANCY WILSON: There was a really cool night when a whole bunch of those people came to my house, a farm near Seattle. Kelly and most of the Pearl Jam, Soundgarden, and Alice in Chains guys showed up. We pulled out guitars and had a hootenanny. It was one of those nights that you never forget, like camping out together. Some people were chemically altered and were giving champagne to my horses when I woke up the next morning. Eddie and [wife] Beth [Liebling] were just like little Eskimos in their sleeping bags.

MCCREADY: Recording Ten, we probably did “Even Flow” 3o times. “Yellow Ledbetter” [the B-side of “Jeremy”] was probably the second take; when we did that song, Ed just started going for it. But [Ten] was mostly Stone and Jeff; me and Eddie were along for the ride at that time.

AMENT: I’d love to remix Ten. Ed, for sure, would agree with me. Three, four years ago, I picked out a cassette, and it had the rough mixes of “Garden” and “Once,” and it sounded great. It wouldn’t be like changing performances; just pull some of the reverb off it.

DAVE GROHL: The first thing I remember of Pearl Jam was hearing “Alive” on the radio while I was living in Seattle. I pictured Mountain or some serious. ’70s throwback. The music just seemed like classic rock to me, so I pictured the singer being some husky, fuckin’ bearded, leather-jacketed Tad type, big and fat and tortured and scary.

GOSSARD: We thought metal was pretty much a joke at that point, but we also knew that it was an area where we could get some fans. Headbangers Ball and Rip magazine, all that stuff. You’re going to do whatever you can to get it going.

We made an “Even Flow” video that never came out that I’m sensitive about, because it was my idea. It ended up being totally rawk: lots of big lights, out on a cliff, definitely comic to look back on now. Hopefully at some point, we’ll be able to laugh at ourselves enough to show that one.

GOLDSTONE: When we were working “Alive,” the initial feedback was, “This isn’t rock enough for rock radio and it isn’t alternative enough for alternative.”

CURTIS: People didn’t know what it was. Once people came and saw them live, this lightbulb would go on.

GOLDSTONE: The band did such an amazing job opening the Chili Peppers tour that it opened doors at radio. You look at how long that record took to explode, and it was exactly how they would have wanted it–not having it shoved down everyone’s throats the first five minutes. People got to discover Pearl Jam on their own: The kid on the street took all of his friends, and then the next time through everyone came.

CATHY FAULKNER: Early on, we always made bets on where Eddie would climb to jump from.

GROHL: I didn’t sit and watch them play until the show in San Diego, where Eddie climbed the fuckin’ lighting rig. I swear to God he was like 250 feet up in the air. It was one of the scariest things I’ve ever seen in my entire life. I’ve seen people cut themselves, I’ve seen people shit, I’ve seen people get beat onstage, and I’ve seen people break bones, break their backs, and get concussions. Honestly, I was horrified. I was really scared that he was gonna die.

VEDDER: In San Diego we were playing with Nirvana and the Chili Peppers. I had climbed an I-beam that you could kind of wrap your hand around. So I got to the top, and I thought, “Well, how do I get down?” I either just give it up and look like an idiot, or I go for it. So I decided to try it, and it was really ridiculously high, like 100 feet, something mortal. I was thinking that my mother was there, and I didn’t want her to see me die. So somehow I finally got back onstage, finished the song, and went to the side and threw up. I knew that was really stupid, beyond ridiculous. But to be honest, we were playing before Nirvana. You had to do something. Our first record was good, but their first record was better.

MCCREADY: I remember after the New Year’s Eve 1991 show, somebody running onto the bus and saying Nirvana had just hit No. 1. I remember thinking, “Wow; it’s on now.” It changed something. We had something to prove–that our band was as good as I thought it was.

1992: Why go home?

JULY 18: The Lollapalooza tour begins, including Ministry, Pearl Jam, Soundgarden, Red Hot Chili Peppers, and the Jim Rose Circus (a collective who liked to lift weights with their genitals, pump their stomachs etc.). JULY 22: “Jeremy” single released. SEPTEMBER 18: Cameron Crowe’s Singles, based loosely on the Seattle rock scene, released.

JIM ROSE: The bile-drinking contests started with [Soundgarden’s] Chris Cornell. There’s an act in our show where one of my members–and it would be a different one every day, because no one can really do it twice in a row–would force seven feet of tubing into their stomach through their nose, and we would pump in beer, ketchup and mayonnaise. Then it was sucked back out, and the result became known as bile beer.One early stop on Lollapalooza, Chris came up and drank it. The very next day, Eddie came up and did it. Then for two days after, [Ministry’s] Al Jourgensen came back on and did it. He started telling Eddie and Chris that he’s drank more than they have. Well, Chris bowed out. But Eddie’s right there every day drinking this stuff. At the end of the tour, Eddie says, “I have drunk two quarts more than you, Al, and I’ve won.”

VEDDER: Just looking for attention, I guess. Every city there’d be some old friend or my wife’s parents, and I’d get to gross everyone out.

CORNELL: There was a second stage at Lollapalooza, so Eddie and me worked up an acoustic set and got some space on the second stage for the middle of the day. We got a golf cart and drove through the crowd to the stage, and it was like the Beatles. There were, like, a hundred people running and screaming and chasing the golf cart. It was the first time I realized what was happening with his band.

BRETT ELIASON: One of the last times Ed went into the crowd was Lollapalooza–in Ontario, Canada. People were literally trying to take pieces of him. He was bloody, his shirt was torn up, somebody had him by the hair.

CURTIS: When “Jeremy” happened and they played at the MTV Video Music Awards, [Sony Music CEO Tommy] Mottola was at the Sony after-party saying, “You have to release ‘Black.'” And the band was saying, “No. Enough. This is big enough.”

GOLDSTONE: “Black” was kind of a sore subject; a lot of other people in the company really wanted “Black” as the next single.

CURTIS: We turned down inaugurals, TV specials, stadium tours, every kind of merchandise you can think of. I got a call from Calvin Klein, wanting Eddie to be in an ad. I learned how to say no really well. I was proud of the band, proud of their stances.

MCCREADY: It was at that time that Eddie took it over. Benevolent dictatorship: That’s kind of the theory. Jeff and Stone running things from one angle, but with Eddie, it was all about pulling back.

AMENT: [American Music Club’s] Mark Eitzel told us, “I saw the video for ‘Jeremy,’ and I fucking hated it.” It was so shocking, this guy we’d just met. He said, “I had a totally different vision of it, and that fucked up the whole thing.” And I agree with him.

MARK PELLINGTON: Probably the greatest frustration I’ve ever had is that the ending [of the “Jeremy” video] is sometimes misinterpreted as that he shot his classmates. The idea is, that’s his blood on them, and they’re frozen at the moment of looking.I would get calls years later about it, around the time of Columbine. I think that video tapped into something that has always been around and will always be around. You’re always going to have peer pressure, you’re always going to have adolescent rage, you’re always going to have dysfunctional families.

RICK KRIM: I have the unedited “Jeremy” video. It was too explicit. The boy sticking a gun in his mouth–it still gives me a chill to watch it. As you can imagine, the band didn’t want to change it. They felt this was their statement. I got on the phone with Eddie on a couple of occasions to argue our position, like, God forbid some kid thinks that’s cool and sticks a gun in his mouth. But it wasn’t a pleasant experience, for me or for them. That was the end of videos for Pearl Jam.

GOLDSTONE: A lot of what happened at that time, and down the street with Nirvana at Geffen, was that who was in control of the music changed. Musicians took the control back. You look at it now, and you think it’s a given. It wasn’t a given.

CROWE: Singles was in the can for a year before it came out. But the success of the so-called “Seattle sound” got it released. Warner Bros. said, “If you can get Alice in Chains, Soundgarden, and Pearl Jam to play the MTV party that we can use to publicize the movie, we’ll put it out.” So I painfully had to try and talk the bands into doing it. Pearl Jam said they’d do it as a favor to me. So the taping happened, and it was… a disaster. It was populated mostly by studio executives and their children, who wanted to see the Seattle Sound.

KRIM: Eddie was hanging with a bunch of his surfer friends from San Diego. I remember fire marshals onstage, Eddie yelling at security guys. They had to shut it down. We had to get Eddie out before they arrested him.

CROWE: They were playing covers, and somebody got into a fight, and Chris Cornell got into it, and I think [Soundgarden’s] Kim Thayil got into it. I remember Eddie yelling, “Fuuuck! What the fuck is this?” and studio executives grabbing their kids and streaming out. I was seeing this whole thing to get the movie released going down the tubes. But Singles came out, and the show aired twice, heavily edited. To anybody who taped it off the air, it’s a real collectible.

GROHL: We were coming from a punk rock standpoint. And Pearl Jam might have been as well. But we wore it on our sleeve a little more heavily than they did. Kurt [Cobain] had made his opinions known: “How could you consider Pearl Jam alternative?” Because their music had, like, guitar leads or whatever. It was pretty ridiculous. And the thing that was so funny to me was that it seemed Kurt and Eddie would have gotten along really well.

GOSSARD: When me and Jeff were at Sub Pop, we left in our wake a rift. That rift was what Kurt attached himself to, and it was perceived in the media as this huge line in the sand.

KRIM: I remember that at the MTV Awards in ’92, Eddie and Kurt kind of made up. I almost remember them underneath the stage, grabbing each other. Clapton was playing “Tears in Heaven,” I think, and they embraced under the stage. King of a magic moment.

GROHL: Yeah, some kind of fucking summit. It was so ridiculous; it had blown out of proportion. I remember the two of them smiling and hugging each other–[sarcastically] and then, all of a sudden, Seattle was okay!

https://youtube.com/watch?v=MS91knuzoOA%3Fecver%3D2

1993-1994: Letting blood

OCTOBER 19, 1993: Vs. released; it sells 950,378 copies in the first week, a record that stands for five years. APRIL 8, 1994: Kurt Cobain found dead in Seattle. JUNE 30, 1994: Gossard and Ament testify before a congressional subcommittee investigating possible antitrust practices by Ticketmaster. AUGUST 1994: Drummer Dave Abbruzzese is fired. DECEMBER 6, 1994: Vitalogy released. DECEMBER 1994: Drummer Jack Irons–Eddie Vedder’s longtime friend–joins the band.

GOSSARD: Ed was trying to break up our formula from early on; he immediately realized that getting bigger wasn’t necessarily going to make any of us happier. The song that you thought was going to be really great for the record wouldn’t necessarily be the one he’d attach himself to. It would be some sort of third riff or silly little song: All of a sudden that would be the one he’d want to work on. Looking back on it, I can appreciate it, and I sort of resent it.

DAVE ABBRUZZESE: I just thought that was ridiculous. I liked where we started out, I liked the notion of going out and playing for ten bucks a show and selling shirts and doing all these things inexpensively and keeping integrity. But, you know, you don’t sacrifice the fucking music that you make. When I got fired, I thought I was meeting with Stone to talk about working [U2 producer] Daniel Lanois. I was thinking, man, we should work with somebody who’ll take this band somewhere and let us be magical.

VEDDER: I call Stone my archenemy in the band, mainly because he’s the devil’s advocate. You could have the best idea that was absolutely nonquestionable, and then he’d bring something up why we can’t just go do it. But it’s really positive. Someone’s gotta do it, and he does, unabashedly.

AMENT: The picture of the sheep on the cover of Vs. was from a farmer down by Hamilton, Montana. That picture at least semi-represented how we felt at the time. As Prince would put it, we were slaves.

CURTIS: For Eddie, it must have been hell, because he could not do a thing. He had crazy stalkers, people threatening to kill themselves, set his house on fire. It made him miserable.

VEDDER: Maybe I wasn’t ready for attention to be placed on me, you know? Also I think it was the practical things I wasn’t ready for, or the legal things that I wasn’t ready for. I never knew that someone could put you on the cover of a magazine without asking you, that they could sell magazines and make money and you didn’t have a copyright on your face or something.

WILSON: Eddie was seeking the advice of Bono a lot. After the shows you’d see Bono and Eddie over in a corner in deep discussion.

BONO: I seem to always take the role of scolding them for not wanting to be pop stars I think they suffer me with some grace. Anyone in their right would do [what Pearl Jam have done]; this is actually how to have a life, how to keep your dignity.

PETE TOWNSHEND: I met Eddie at my solo show in Berkeley [California] in 1993. I recognized him in the audience, but he looked bemused, a little lost. [Afterward] I spent an hour with him. It could have been ironic, the play I was performing–about old, worn-out stars trying to pass on their “wisdom” to younger performers.

I can’t remember what I said. Probably something about just accepting who he obviously was–a new rock star. I think maybe he could see the new rock’n’roll rules of his life being rewritten, and he didn’t like them.

ROSE: I get a call from Eddie; he says, “It’s Roger Daltrey’s 50th birthday; I got a cake for him, why don’t you come with me?” So we went, and everybody was there: Alice Cooper, Lou Reed, Townshend, Sinéad O’Connor. So we all met up at Carnegie Hall, we gave Roger the cake, and then Eddie and I went into his dressing room and he hands me a metal chair, and says, “You throw the opening pitch,” I look around, and it’s just these gorgeous chandeliers and mirrors and gold-plated lights. And I had been drinking.

By the time it was through, there was nothing left. Even the toilet was broken down, just a pipe gurgling water from the floor.

VEDDER: I think I threw a wine bottle at a mirror and it exploded. At some point I cut my hand and started writing I HOPE I DIE BEFORE I GET OLD in blood. Which was really good.

We got a bill from Carnegie Hall for $25,000. It was maybe two grand, tops–like, a mirror and a paint job and a couple lightbulbs. We talked them down. They also said they’d never have rock’n’roll bands in [Carnegie Hall] again. Which is only right.

TOWNSHEND: I heard about it afterward. No one thought it was particularly well executed. But after all, he’s a fucking surfer!

GOSSARD: It was the most stressful and unnerving time. I was going out of my mind. The band has never been more successful, but we can’t all be in a room together. Everything’s dramatic and big.

VEDDER: I remember tearing up my hotel room in a complete rage when I found out [that Cobain had died]. We played that night [near Washington, D.C.], and I still question that. [Fugazi’s] Ian MacKaye was there, and he offered to take me in that night. So I went to get my suitcase from the hotel, but I didn’t have a key, so I had to go up with the maintenance guy to let me in the room. When he opened the door, I just looked at him and said, “You have to understand what happened today.”

BRENDAN O’BRIEN: Vitalogy was a little strained. I’m being polite–there was some imploding going on.

GOSSARD: Vitalogy was the first record where Ed was the guy making the final decisions. It was a real difficult record for me to make, because I was having to give up a lot of control.

ABBRUZZESE: Stone would kind of be the bridge of everyone’s gap. When he stopped taking that role, the music changed, and [the band] became a less communicative, more whispery place.

GOSSARD: And Mike was really starting to struggle with his addictions, alcoholism and cocaine.

CURTIS: Mike was definitely not a good drinker. He’d do stupid things: taking his clothes off, passing out, pissing in the corner.

GOSSARD: It was perfect for us to wallow around in some controversy with Ticketmaster.

AMENT: That whole [Ticketmaster] thing was a joke. The Department of Justice used us to look hip. Stone and I spent a week with our lawyer, John Hoyt; he was drilling us with serious questions that we were [supposedly] going to get asked, and then it didn’t feel like we got to utilize any of it. It made me a lot more cynical about what goes on with the government.

VEDDER: Eventually they came out with a press release that basically said, “The Department of Justice has ceased its investigation of Ticketmaster. No further investigation will take place.” That was it, after a year of struggle. It was really amazing to be right up close and get absolutely stomped on by a huge corporate entity.

O’BRIEN: And Dave Abbruzzese, for whatever reason, he and Eddie didn’t get along.

ABBRUZZESE: I felt like there was a time when I had a good friendship with that guy. And then all of a sudden I didn’t know him. But I understand–shit, if I was freaking out about stuff and having panic attacks, I can’t even begin to fathom what the hell he was going through. I give it up to him just for surviving it.

AMENT: Also, with Dave, musically, when you’d say, “I want this to sound more like the Buzzcocks,” I don’t think he related to that at all. He was a technical guy, and we all played by feeling, or by seeing bands.

GOSSARD: It was the nature of how the politics worked in our band: It was up to me to say, “Hey, we tried, it’s not working; time to move on.”

ABBRUZZESE: Stone showed up as a man, and as a good friend. I hope to one day tell him how much I appreciate [that].

I had just soured. I didn’t really agree with what was going on. I didn’t agree with the Ticketmaster stuff at all. But I don’t blame anyone or harbor any hard feelings. I’d be lying if I said I wasn’t furious and hurt for a long time. But now I just wish there was more music from the band I was a part of.

1995: Push me, pull me

FEBRUARY: Band records Mirror Ball with Neil Young. APRIL 12: Eddie Vedder begins a tour with Mike Watt and Dave Grohl. JUNE 16: A U.S. tour of alternative venues (those without Ticketmaster affiliation) begins in Casper, Wyoming. JUNE 24: After being hospitalized for food poisoning, Vedder collapses midset during a show in San Francisco’s Golden Gate Park. The tour’s remaining dates are canceled.

GLORIA STEINEM: I first met Pearl Jam because they were performing, with Neil Young, for the 22nd anniversary of Roe v. Wade at an annual concert that Voters for Choice does in Washington, D.C. When the issue of late-term abortion was emerging as a crucial one, they asked to have a briefing so that they would truly understand the issue. Maureen Brittel of Voters for Choice, who was one of the women whose story convinced Clinton to veto the legislation that would have outlawed late-term abortions, came, and the whole band was there. You know, it’s a level of caring.

Since then we’ve all become friends. And, of course, now I’ve acquired a value to my nephews that I never had before.

O’BRIEN: I got a call from Kelly. He said, “Don’t be surprised, but in an hour, Neil Young is going to call you and want you to produce a record with him.” He calls me and says, “Can you come tomorrow, or the next day?” We did [Mirror Ball] in a week and a half.

GOSSARD: That came at a time when we needed it, that Neil thought we were a band that would be good to make a record with. He probably felt sorry for us. He made it all right for us to be who we were. He’s not taking his career so seriously that he can’t take chances. Suddenly, our band seemed too serious.

GROHL: For anyone like me or Kris [Novoselic, Nirvana’s bassist] or Eddie, who may have been somehow disillusioned or jaded or just numb, being around [Minutemen’s] Mike Watt in the studio for just one day renewed that feeling of excitement. He started talking about putting a tour together: He wanted to have Eddie play guitar and me play the drums and he’d play the bass. For three people who were so starved for some sort of thrills, it kind of blew up.

Eddie and his wife’s band, Hovercraft, had this van they had spray-painted silver–it just looked like a cop magnet; it was such a bad idea. And we had this red Dodge extended van that we called Big Red Delicious. We all had CBs, and through a lot of CB conversations driving through the middle of nowhere, I realized that Eddie is a fuckin’ funny motherfucker. I think that for Eddie, at that point, a lot of things had been knocked out of perspective. That tour brought a lot of it back together. We were playing three sets a night for 12 days in a row, with a ten-hour drive every night.

VEDDER: It was really great until the middle, and then I think I couldn’t handle it. There were people throwing coins in Chicago–Minutemen fans who didn’t want to see a corporate-rock-band guy on the same stage as Watt. And I was frustrated. I was thinking, you, “I’m supporting your guy; he’s my hero too.” Goddamn. I understand where they’re coming from. I might have been one to throw the coin myself.

AMENT: We were so hard-headed about the 1995 [Pearl Jam] tour. Had to prove we could tour on our own, and it pretty much killed us, killed our career. Building shows from the ground up, a venue everywhere we vent.

ELIASON: God bless ’em for trying, but people didn’t care; they just wanted them to play. That was the first time they felt backlash from fans, which is something they weren’t used to.

KARRIE KEYES: Looking back, I’m surprised they made it through, After the ’95 tour, they took some time off.

ROSE: Okay, so back to Mexican transvestite wrestling. Back in ’95, Eddie turns up at a show, and he’s wearing a wrestling mask, and he gives me and my circus performers masks. No one knew who Eddie was, so we could walk around in the crowd and do these little mock fuckin’ wrestling matches. We started thinking, wow, let’s do wrestling as part of the show. And, well, what if the rules are changed? What if they wear dildos? What if the first one who can force it into the other one’s mouth for a 1-2-3 count wins? And it’s Mexican transvestite wrestling.

So from ’96 to ’98, we basically did a wrestling show with the Jim Rose Circus opening for it. And because I’d told people that Eddie had helped me come up with the idea, people decided Eddie was Billy Martinez, “The Barrio Bottom,” underneath that mask. I had hundreds of kids in every city I went to asking, “Is Eddie really Billy Martinez, ‘The Barrio Bottom’?” They don’t even know what bottom means in gay culture or whatever.

I ran into Eddie a year later–I was really dreading running into him because I knew it’d been all over the press–but he just smiles at me and goes, “I’ve been asked about that Mexican transvestite wrestler thing a hundred times this year.” Just looked at me and rolled his eyes.

https://youtube.com/watch?v=qM0zINtulhM%3Fecver%3D2

1996-1999: Even flow

AUGUST 27, 1996: No Code released. FEBRUARY 3, 1998: Yield released. APRIL 1998: Jack Irons quits; drummer Matt Cameron (ex-Soundgarden) joins. AUGUST 1998: Single Video Theory long-form video released. NOVEMBER 1998: Live on Two Legs released. DECEMBER 23, 1998: “Last Kiss” released as fan club-only single; radio stations across the country as soon playing it. JUNE 8, 1999: “Last Kiss” is re-released as commercial single. It reaches No. 2 on Billboard‘s singles chart, higher than any other Pearl Jam single.

O’BRIEN: By No Code, things were a bit more relaxed. It was really a transitional record. We had a good time making it. Jack [Irons] had just joined the band. Jack was like a session pro, a session-drumming assassin. Everybody was on their best musical behavior around him.

GOSSARD: No matter what, you’re going to have a time when some people are going to lose interest in you. We could still sell out live, which took some of the ego sting. But there was definitely a sense of us not delivering the goods in the way that the masses expected from us. Then, I was straining at it. We didn’t talk about it. Talk about what? How do we get people to like us again?

AMENT: During that black-hole period, there were just a lot of power struggles going on. But Yield was a superfun record to make. And so much of it was Ed kind of sitting back; we worked on all of our songs before we worked on any of his stuff. That was a huge thing.

O’BRIEN: I remember there was a concerted effort to really put together the best, more accessible songs they possibly could.

MCCREADY: We were hanging out a lot, Eddie and me, talking politics, life, surfing, music. I remember telling him we need to be very cognizant of the powers that be, because it’s critical to our survival. We needed to go out and play music, and enjoy it, within this capitalist structure. To still support those causes, but to work through the established channels.

CURTIS: And then Jack left. He was a guy whom everybody had wanted in the band, and initially he really had a great effect on everybody. But he stepped into the PJ world, and it was pretty overwhelming. He wasn’t able to continue.

VEDDER: I only talked to Jack recently for the first time in quite a while. I think that him deciding that he wasn’t going to be in the band really hurt.

MATT CAMERON: End of tour, Eddie said, “Hey, man, you want to join?” I said, ‘Let me think about it.” So I said, “I’ll do a record, do a tour, if you wouldn’t mind me doing it that way.” I haven’t really joined them long-term.

Working with them is totally pro. They can sell out any arena anywhere in the world. They’re kind of in a special league. They can tour really comfortably but keep it kinda small as well. Punk-rock arena rock is the way they approach it.

SILVER: In Texas, a very, very drunk Dennis Rodman refused to leave the stage no matter what they did or how firmly they asked. He would go behind Stone and start strumming on the guitar while Stone was playing or just walk in front of Stone and talk about how incredible each guy was. They finally got him a stool and sat him in front of the drum kit, and he sat there for a song looking like the kid in the corner pouting; then he looked back and realized he didn’t know the drummer. He spent what looked like eternity to me leering at Matt like, “Who are you? Show me what you got.”

GOSSARD: “Last Kiss” was one of my favorite moments in their band’s history.

VEDDER: I had found a copy of [J. Frank Wilson and the Cavaliers’ 1964 version of “Last Kiss”] that day and then learned it. We were playing a small club show in Seattle, and Matt and I did it at the end of the night.

GOSSARD: Brett recorded it later, we spent $1,500 mixing the single at home, and it was our biggest song ever. The same performance that was at soundcheck. Just us trying to sound like a ’50s song and and sounding half-assed. Ed’s interpretation is sentimental and beautiful, and it’s not ironic, or clever, or sarcastic.

CURTIS: There was this pressure [from the label] to release it commercially. We came up with the idea that you can release it, but you’ve got to give all the money away.

VEDDER: “Jeremy”‘s kind of a teen death song, too. We’ve done really well with teen death songs.

https://youtube.com/watch?v=CxKWTzr-k6s%3Fecver%3D2

2000: Gods’ dice

MAY 16: Binaural released. MAY 23: Pearl Jam begin European tour in Lisbon, Portugal. JUNE 30: Nine fans are trampled to death in the audience pit while Pearl Jam perform at the Roskilde festival in Denmark. AUGUST 3: The band begin a U.S. tour in Virginia Beach, Virginia. SEPTEMBER 26: Twenty-five live albums are released (from the European tour).

VEDDER: I never really spoke with anybody about Roskilde. It’s the most brutal experience we ever had. I’m still trying to come to grips with it.

Right before we went on that night, we got a phone call. Chris Cornell and his wife, Susan, had a daughter that day. And also a sound guy left a day early, ’cause he was going to have a child. It brought me to tears, I was so happy. We were walking out onstage that night with two new names in our heads. And in 45 minutes everything changed.

CURTIS: I think if we had felt responsible in any way, they couldn’t have played again. There’s been plenty of times in Pearl Jam’s career where you see people go down and you stop the show.

GOSSARD: Well, this particular show, the barrier was 30 meters away; it was dark and raining. They’d been serving beer all day long. People fell down; the band had no idea.

CURTIS: The reason those people died was that no one could get word out what was happening. It was just chaos. There was a lot of Danish press that said we were inciting moshing. It wasn’t during a crazy part of the set; it was during “Daughter.”

GOSSARD: We were part of an event that was disorganized on every level. Mostly I feel like we witnessed a car wreck. But on another level, we were involved. We played this show, and it happened. You can’t be there and not have some sense of being responsible. It’s just impossible. All of us spent two days in the hotel in Denmark crying and trying to understand what was going on.

VEDDER: The intensity of the whole event starts to seem surreal, and you want it to be real. So you sit there with it, and you cough it up and re-digest it. You still want to pay respect to the people who were there or the people who died and their families. Respect for the people who cared about you.

A friend of an Australian guy named Anthony Hurley asked if I would write something for the funeral. That was just hands-down the hardest thing I’ve ever had to do–not really knowing what was appropriate, not knowing how the family or friends felt; maybe I’m the last person they’d like to hear from. But it meant a lot to them, and it really helped me. I think it also helped the rest of the guys.

Hurley had three younger siblings, and they said he really cared about our band, and that’s why he was in the front. And that he was actually doing something he loved during his last minutes. His sister and a friend of his–who was with Anthony that night–came to Seattle and saw our last two shows. And that was nice, spending time with them. That’s been really important.

AMENT: Some of us thought maybe we should cancel the [North American] tour. I felt if we cancel, what are we running from? It made us deal with it every day on some level, and that was the most positive thing we could do. The shows were all reserved-seating, which made it a lot easier. At first, it was hard to look at the crowd. A couple kids I saw at Roskilde, they’re burned in my memory forever. Sometimes, when you’re looking at a crowd, you can’t help but see those faces.

The Vegas show on the U.S. tour was pretty heavy. That afternoon was the first time we’d played the Mother Love Bone song “Crown of Thorns.” Kelly and Susan Silver and my parents are there, my whole family, and all of a sudden, playing that song, it was the first time I properly reflected on what we’d gone through and what a journey it’s been. And that moment was reflected in a purely positive way, feeling blessed, happy to still be playing music.

CURTIS: With the [live albums], we’d been talking about the idea for years, but it had been prohibitive. We’d always recorded our shows, and now our sound engineer said it could be done cheaply.

ELIASON: For the Europe set, they gave me two weeks to mix 25 shows. In man-hours, it took me 15 hours a show. My assistant stayed here at the house and we just went, “Tag, you’re it.” One slept while the other worked.

But it was worth it. We had 14 records in the Top 200! Nobody’s ever done that.

2001: Present tense

FEBRUARY 27: Twenty-three more live albums released (from the first leg of 2000’s North American tour). MARCH 27: Twenty-four more live albums released (from the second leg of the North American tour) MAY 1: Touring Band 2000 DVD and video released.

CURTIS: The nest studio album is our last under our contract. We’re not going to re-sign with a major, under current ways of thinking.

GOSSARD: We’ve kind of played small ball. And it’s been great.

GOLDSTONE: Like any great band, there’s peaks and valleys. If the continue to do what they want to do, they’re going to be one of those bands that’s around for 20 years. It’s not that easy to achieve.

BONO: I’m a fan of the Pearl Jam organization, of what you might call the culture around the group. It’s like the Grateful Dead. We’ve been thinking a lot about that West Coast way of doing business. I must say, I’m not sure how long U2’s going to have energy to take on the mainstream. And the Pearl Jam/Grateful Dead model is something to be really proud of. They exist entirely unto themselves. They don’t depend on the media, don’t depend on the radio.

GOSSARD: If we’re at all like the Grateful Dead, that’s the ultimate–a band believing in their own weird little world and people loving it because it is in a little bit of a vacuum.

AMENT: I still don’t think we know what’s going to happen, but we’re much more relaxed about it. We’ve had a nice little ten-year run.

CORNELL: Better than any other band almost in history to have had that kind of enormous success, they dealt with it really eloquently. I think that set a great example to other musicians that, you know what, you can actually control the media spotlight. I think they stayed vital. The records they made didn’t necessarily appeal to the same number of fans who were into Ten, but they appealed to a lot of people. They sold millions of records without having to make videos and without having to do an overhyped press campaign for each record.

VEDDER: I’m writing on ukulele a lot [lately]. It’s an interesting instrument, ’cause it’s four strings, and the fewer strings, the more melody, I’m finding. And it’s also about the smallest instrument you can play. So I’m just shrinking. As for the future, right now I have the luxury of not thinking about it at all. At the moment everyone is getting to figure out things about themselves. After everything that’s happened, it’s just really good that we’re not trying to do what we usually do right now. That would just be unbearable.

But I have a feeling that recording again is going to be a very similar thing. It’s going to be the same kind of practice place, and the same kind of walking around, plugging in. And Stone’s gonna plug in first and play really loud while the rest of us are trying to talk and say hello. We’re gonna yell out, “Does anybody have a tape recorder?” And then they’re gonna find a ghetto blaster from the back room, and then we’ll play some songs, and we’re gonna learn a couple of them, and then I’m gonna go home and drink beer.