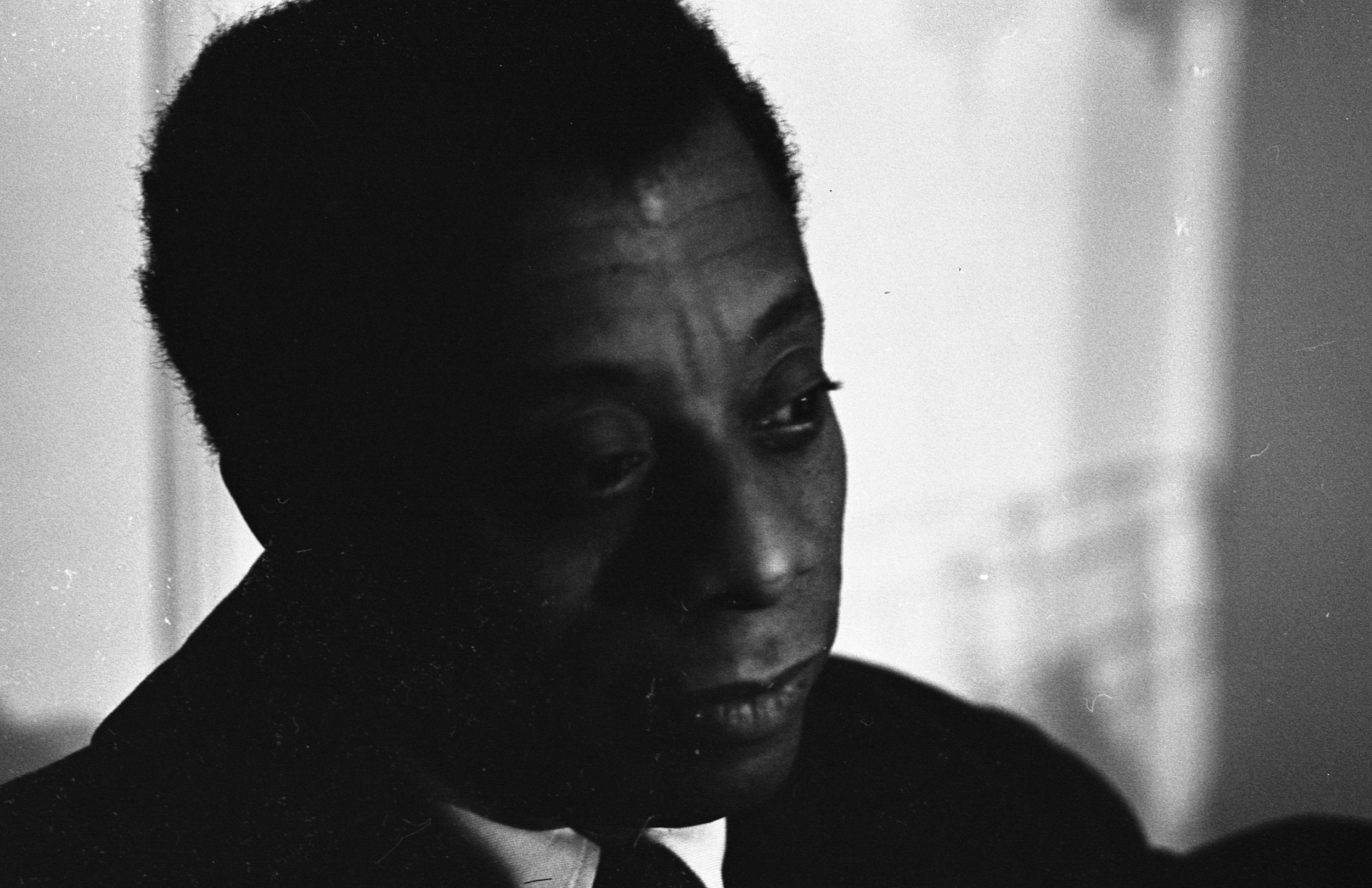

Raoul Peck’s I Am Not Your Negro played at three New York theaters during its opening weekend. I attended the Sunday morning screening at the Magic Johnson Theatre in Harlem, the neighborhood where James Baldwin was born. (This was no grand writerly gesture; it was just the only theater in Manhattan that still had tickets on Fandango.) The documentary uses Baldwin’s unfinished manuscript Remember This House—which sought to tell the story of America through the lives of activists Medgar Evers, Malcolm X, and Martin Luther King Jr.—to detail America’s deleterious relationship with African Americans, a struggle that’s very much ongoing.

Baldwin’s words are often considered prophetic, and a majority of the audience in my showing were well into adulthood, presumably well aware of what it feels like to be black in the United States. Going into it, I’d already braced myself for reactions to the film: As narrator Samuel L. Jackson–in one of his subtler and contemplative performances–recited Baldwin’s words, viewers in the theater responded with chorus of “Mm-hmm.” They mostly came from women, and carried the reflexive, soulful tone of a mm-hmm that confirms a quote as truth. I Am Not Your Negro is the sort of film that is built to elicit plenty of those. “White is a metaphor for power,” Baldwin says via Jackson at one point. (“Mm-hmm.”) For the black moviegoers who filled that auditorium—the ones who’re constantly gaslit to believe that power structure doesn’t exist—the film serves as an affirmation, not a revelation. It’s also why it falls just short of being an essential piece of work.

The 30 pages of Remember This House that Baldwin managed to finish before his death was enough for a tidy one-and-a-half-hour arc. Because the film is also tied into the current struggle against white supremacy–I’ve been told it’s supposed to get me ready for the next four years, too–historical protest footage and images of destroyed black bodies are interspersed with recent trauma. Much like the generations of Jim Crow violence shown in Ava DuVernay’s documentary 13th, the transitions are hauntingly seamless. Peck’s delicate filmmaking and Baldwin’s vivid prose interact in a way that neither feel like tableau for the other—rather, they’re constantly conversing.

After leaning toward a traditional documentarian approach in the film’s more autobiographical first half, Peck uses a surreal sleight of hand to visualize Baldwin’s dark thesis—that white people have created the “nigger” as something to be reviled in order to maintain their purity. In one of I Am Not Your Negro’s humorous moments, Baldwin looks flustered when a Cambridge lecture hall of white students stand and applaud after he foretells of a “very grave moment for the West.” Moments later, we see images of political figures (the Clintons, Donald Trump, former Ferguson police chief Thomas Jackson) delivering feckless apologies as they’re transparently imposed upon a red sky bleeding through a silhouetted neighborhood. The goal is clear: To poetically restate the limits of white absolution, a self-serving method that rarely concerns the victimized. Later on, white actors thriving in Hollywood-constructed idylls—two of whom Baldwin calls “most grotesque appeals to innocence”—segues into images of lynched black bodies and an inhuman white mob. They jarringly connect in a way that illustrates America’s delirium. Those images don’t simply juxtapose but bleed into one another.

The craft is exceptional, even if the form itself is limited. I Am Not Your Negro jives with the platitude “James Baldwin is the voice for our times.” I have to question whether that’s ever been in doubt. Baldwin the Prophet isn’t a new discovery: There’s a clarion that arises preternaturally from his works. His words scarcely needs further elucidation or contextualization because they do a fine job of providing both on their own. The interviews and the lectures fluidly compose the larger story arc, but taken apart, they’re still rich philosophical microcosms. Baldwin’s momentous appearance on the Dick Cavett Show—where he verbally dispatches of philosopher Paul Weiss’s argument that he’s making too big of a deal about race—arrives as a late film triumph. Baldwin disassembles through palpable logic: Why is he making an “act of faith” to trust white people when systemic prejudices against black people flagrantly advise otherwise? It’s a minute thrilling enough to elicit a guttural “Get him!” from a brother in the back of the theater. Still, the argument is just as earth-shattering as a YouTube clip.

Baldwin’s autobiographical ruminations and his intimate throughs on Malcolm, King, and Evers provided the more compelling moments. Their appeal wasn’t just because they were informative; of course, it was Baldwin’s empathetic voice (via Jackson) that made these stories riveting. They’re not tales of martyrdom, but of crippling loss—these were beloved men who died before their 40s. There’s a felt heartbreak when Baldwin remembers Malcolm X (“And held him in that great esteem that’s not easily distinguishable, if it is distinguishable, from love”) and evoked despair when he recounts receiving the phone call about King’s shooting (“The record player was still playing: ‘He’s not dead yet. But it’s a head wound.’”). I Am Not Your Negro never loses that mournfulness for heroes too often romanticized, but rarely humanized.

In another highlight, the film switches its attention to Sidney Poitier’s 1958 vehicle The Defiant Ones, which follows a two escaped prisoners—black and white (Noah Cullen)—as they survive while still shackled together. At the climax, Poitier’s character is escaping on a train while Cullen is running after him, just out of his hand’s reach while escaping authorities. So, in a selfless act, Portier jumps off the train.“The white liberals downtown were much relieved and joyful,” Baldwin says. “But when black people saw him jump off the train, they yelled, ‘Get back on the train, fool.’” The signature boldness cracked through Jackson’s voice by the end of the story, landing the punchline with knowing sense of indignation.

The Harlem audience got a kick out of it, too.