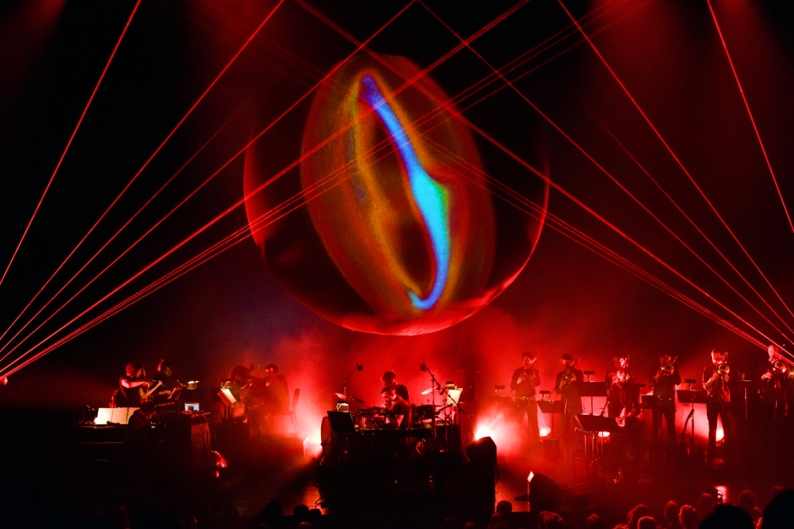

Lasers! Orchestral strings! Brass! A violin bow sawing an electric guitar! A giant, floating planet! Cloudy, trippy lights! Auto-Tuned space voice! More lasers!

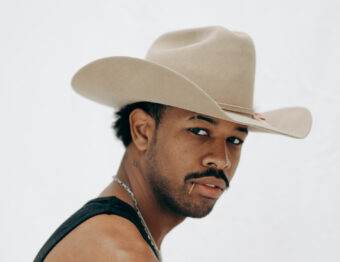

Although Sufjan Stevens has been blurring the lines between the visual stadium-rock bombast of Floyd and Zep and Phish and his own indie-folk-electronic experiments for some time now, the distinction seemed even more obscure at Planetarium, a downright proggy collaboration between Stevens, the National’s Bryce Dessner and contemporary classical composer Nico Muhly that opened at Brooklyn’s BAM theater last night. The piece, which showcases the trio respectively playing samplers, guitar, and keys, alongside a string quartet and seven(!) trombones, features a song for each of our solar system’s planets. Not to mention the sun, our moon, and the disgraced dwarf planet Pluto (included “out of pity,” according to the program). Musically speaking, it was a nebulous concoction of art-rock and neoclassicism with lyrics about dropping one’s knickers at Methodist camp, and it had some truly trippy moments.

But before the mix of well-dressed older arts patrons and T-shirt-clad Brooklyn beardos bathed in the blues, greens, and solar-flare reds of their light show, the crowd took in works for string quartet as composed by each of Planetarium’s contributors. In “Little Blue Something,” a somewhat haphazard-sounding piece by Dessner, notes skate over one another, coming together in euphonic clusters, but there was something about the rhythms, or maybe the miking of the instruments, that made the piece feel rushed and disjointed. Violist Nadia Sirota somewhat addressed these inconsistencies when she explained that the piece was a world premiere. Next up was a collection of four pieces by Stevens taken from his 2001 electronic album Enjoy Your Rabbit, each with titles like “Year of the Horse,” “Year of the Dragon,” etc. Generally, these sounded more polished than Dessner’s, thanks to new string arrangements by Muhly and first violinist Rob Moose that showed off his instruments’ timbral capabilities for squeaky harmonics and bendy sliding sounds. Muhly’s own eight-movement quartet, “Diacritical Marks,” was unsurprisingly the most accomplished-sounding composition, which began with swelling violins and percussive cello. Some movements displayed Muhly’s knack for mixing the atonal with more pleasant sounds and others showed off the quartet’s ability to make notes quiver and shiver as their fellow musicians played simple, jazzy rhythms. Overall, the quartets only underscored that full-time composer Muhly had an expected leg up on his mates in terms of composing classical music.

But Planetarium itself, which began after the unveiling of a giant sphere over the musicians at intermission, proved to be something more than classical music, mostly due to its rock drums and Stevens’s myriad electronic instruments, not to mention the vocals and heaps upon heaps of chimes (despite the fact that there’s no wind in space). Lyrically, the songs seem to have nothing to do with the cosmos, instead finding Stevens singing mostly about loneliness, sorrow, and alienation in the context of “Roman gods” and “Japanese fables,” according to the program (though the lyrics often seem more personal), as well as the previously mentioned, and very personal sounding, Methodist indiscretions in “Venus.” As Stevens sang, Muhly cued the trombone septet, leaning over his celeste, and Dessner stayed relatively still, making what we guess were ambient noises on his guitar. The rich, bellowing sounds of the trombone gave a lot of power to many of the songs, even when Stevens sang lines like “Jupiter is the loneliest planet.”

Just as important as Stevens, Muhly and Dessner were lighting designer Ben Stanton, projection designer Deborah Johnson, and laser designer Eliav Kadosh. The pair’s work drove the intergalactic experience home by projecting cloudy lights on the globe, imitating solar flares when it was supposed to be the sun and projecting more laser arrays than a Dark Side of the Moon laser light show. (Surprisingly, the one thing that was most unlike any rock show was the lack of cell phones snapping photos, despite the show having more overwhelming visuals than the average National concert.) Throughout the show, the lighting matched the tone of the music, which overall erred more often to the darker side, especially for “Pluto” and “Saturn.” Although the music owed an obvious debt to classic rock, especially with Stevens’ insistence on affecting his voice with electronics on each song and Dessner’s bowed guitar on “Earth,” it shared just as much with the minimalist music of Philip Glass and quirky work of film-score king Danny Elfman, using drawn out drones and repeated melodies.

When the threesome ended the hour-long work, it ended on a down note, with Stevens singing “I’m sorry” in “Mercury.” But considering the standing ovation the group received, the Brooklyn audience had accepted whatever it was he was apologizing for. After leaving the stage, Stevens, Muhly, and Dessner returned to the stage without their backing ensemble for a mercurial piece that congealed into an droning, vocodered closer to the evening: Judy Garland’s “Over the Rainbow.” Awash in blue and purple lights, it was all the more poignant considering Jeff Beck and Eric Clapton have both covered it, too. Is this the new classic rock?