This summer — Nine Inch Nails' first as a living, breathing entity in four years — Trent Reznor has been taking the stage alone. Muscular and short-haired, he opens his shows by marching to a synthesizer in full view of tens of thousands of festivalgoers, all of whom had strong reason to believe they might never see this band again. Usually wearing a sleeveless black t-shirt, heavy boots, and cargo shorts, he begins to sing the stealthy "Copy of A," a track from Hesitation Marks, the imminent new NIN album those same festivalgoers had equally strong reason to believe might never exist."That moment is our reintroduction," says Reznor, seated on a red leather couch in a conference room at Hollywood's posh Soho House, a cocktail-jazz version of Nirvana's "Lithium" clinking quietly in the background. "It's supposed to challenge the audience. I didn't want to come out and signal that we're just a band playing songs you know we're going to play."

[caption id="attachment_id_190580"]  Photo by Baldur Bragason[/caption]

Photo by Baldur Bragason[/caption]

He cocks his head, as if considering a problem he's still in the process of solving. "I haven't had a chance to live with the show yet, so it's hard for me to tell what people think."

Indeed, these things take time, but over nearly a quarter-century of Nine Inch Nails, Reznor has learned that if you tackle the hardest things first, the rest of it has a way of working out.

For roughly 80 percent of the band's existence, a bet on Trent Reznor sitting in a room like this discussing his career in early August 2013 would've drawn long odds. The reasons range from the mundane (his industrial baby-step years spent in Cleveland) to the medical (a personally confused, chemically indulgent '90s) to the plainly literal (a burnt-out Reznor told a 2009 Bonnaroo crowd, "This is our last-ever show in the United States").

Yet here we are, in a brief window between gala appearances at Lollapalooza and San Francisco's fellow multi-day extravaganza Outside Lands, with gigs on the European muddy-field circuit approaching quickly, and solo North American arena dates looming on the horizon.

"I'm at a peak of exhaustion right now," says Reznor, who minus a scowl (and plus some longer pants) largely retains his onstage guise offstage. He's sipping from both a cup of coffee and a can of Diet Coke, and is a polite, even friendly presence, firm with his handshake and quick with a smile. "I was shooting a video till three in the morning. The last few weeks have been terribly intense. The way I work is that up to the last second stuff looks like shit, and at the last minute it comes together. But I feel like I've done good work, and there's still an audience there. I'm not looking out at the crowd and seeing a bunch of orthodontists. It's new faces that look like the old ones, if that makes any sense. It feels valid to be back."

That's because more than at any time since the release of 1994's self-loathing alt-angst classic The Downward Spiral — an album to which Hesitation Marks ruefully nods across the decades — Nine Inch Nails, and their formerly tortured and wraithlike leader, once again have the zeitgeist on a leash. The man who once made it a mission to jolt rock beyond its guitar/bass/drums doldrums has delivered a heavily electronic LP into a world where binary code is now just accepted as what makes music go. The band's ticket sales are stronger than ever, and the David Lynch-directed video for self-reflexive first single "Came Back Haunted" quickly earned more than two million YouTube views. Reznor's sound — confrontational, fiercely technological, pretty damn catchy — now reverberates through the banging aggression of American dubstep and the visceral clang of so much contemporary hip-hop.

https://www.youtube.com/embed/yA281OuU3rk

For English producer Evian Christ, who contributed to Kanye West's electronically noisy Yeezus, "There's been a resurgence in the influence" of Reznor-indebted music. "I'll always be grateful to Trent for sparking my interest in music that I would otherwise never have been aware of." And in a period when the digital world is throwing off the brightest, sexiest creative sparks, Reznor has diversified, pointing his sharp mind at the puzzle of streaming music, working with Beats by Dre to develop what the company hopes will be the ultimate subscription-based music service, due to launch in a limited fashion this fall.

But Reznor knows better than most that riding these socio-cultural waves is as much a matter of luck as sweat. "There's always been an element of 'right time, right place' to Nine Inch Nails," he says. "When we stepped onstage at Woodstock '94, I could sense it. I get goosebumps thinking about it now. Like, 'I don't know how we did this, but somehow we've touched a nerve.' And then as you move forward, you realize that you can't set yourself up for doing that again. So the fact that our music may or may not be in the air now and people seem eager for it, and that I'm working on something with Beats that's a marriage of humanity and technology, which is sort of what my music has always been about, and I'm doing this after years of working on my own trying to figure out how best to get music to the people who want to hear it — you can't plan for those things. It's just the way the world works."

[featuredStoryParallax id="97709" thumb="https://static.spin.com/files/130821-Nine-Inch-Nails-Outside-Lands-01_0.jpg"]

At some point in the not-too-distant future, Trent Reznor's sons, two-year-old Lazarus and one-year-old Balthazar, are going to hear their father sing "Closer," complete with its chorus of "I wanna fuck you like an animal."He's been airing that song in concert these days, and admits he hasn't quite thought through the long-term implications. "When I was 25, people used to say to me that having kids would change you, and I'd roll my eyes," says Reznor, who married singer Mariqueen Maandig in October 2009. "I don't know what it'll be like when they read old stories about my addiction or listen to the older songs. I do know that I caught myself swearing in front of them during a road-rage moment and was worried they'd parrot it back."

He shakes his head. "It's a humbling thing, having kids. One of my sons came to rehearsals, and now he says Daddy's job is 'go play loud music.'"

I'm not as afraid of judgments as I used to be. I just want to do the best I can do, and not squander any more time than I already have when I was high. That's my main concern.

That job, and Daddy's relationship to it, is very different now. While Reznor takes pains to point out that he'd only ever said that Nine Inch Nails were taking a break from touring — the band had been on the road almost constantly from 2005 to 2009 — he does admit that his attitude about the project that made him rich and famous had profoundly shifted.

"The main thing was that I didn't want to be on an endless rock-band tour with Nine Inch Nails," he says. "And I said that adamantly enough to force my hand at trying something new. It was like with getting sober: I announced to the world that I was sober so that I'd be held accountable. What I feel bad about is that this is some 'KISS Final Tour of Mid-2013' idea. I get that people might feel that way, but I've given up on trying to manage the spin on things. Nine Inch Nails felt right for me to do, and that's because it felt uncomfortable in a lot of ways. That's usually a sign for me that something might be interesting."

He last felt such seductive discomfort shortly after getting off the road in 2009, when director David Fincher approached him and Reznor collaborator Atticus Ross about scoring 2010's The Social Network. "The process of working on that was surprisingly great," Reznor says. "It was like the first Nine Inch Nails van tour — some of the most rewarding work I've ever done. At the time I'd just gotten married and was feeling like I was getting old to be touring, and I thought film-scoring could be a reinvention."

Reznor, who relocated from New Orleans to Los Angeles in 2005, won an Oscar for that moody, hypnotic Social Network score, and he and Ross worked with Fincher again on 2011's The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo. But those fulfilling experiences, he explains, were aberrations. "Seeing more about how Hollywood operates, you recognize that making movies is an economic calculation. If, by chance, a high-quality film comes out, that's good, but it's not about executing some great vision. Working with someone as smart as David Fincher isn't normal. I love the idea of making films, and hopefully want to make one of my own someday, but it wasn't a world I wanted to spend more time in."

Wait. So what Trent Reznor really wants to do is direct?

"I'm thinking a super low-brow bro comedy," he says dryly. "I'm into nut humor."

Even while Reznor was scoring the exploits of interpersonally awkward coding moguls and Swedish cyberpunks, he never stopped making music for himself. "Trent is always experimenting in the studio," Ross says. "He doesn't make some big announcement ahead of time and say, 'This fragment will someday be a Nine Inch Nails song,' but I knew that he'd return to Nails eventually."

The more vexing question was what Nine Inch Nails should be in the second decade of the 21st century. Sober, happily married, wildly successful in his other musical pursuits — what reason did Reznor have for bringing the band back to life?

[caption id="attachment_id_134339"]  Getty Images[/caption]

Getty Images[/caption]

"The unglamorous story is that I owed Interscope a couple of songs for a greatest-hits package," he says bluntly. "I thought that might be a good excuse to try some new things, and 'Satellite' and 'Everything' came out. It was obvious that I would have censored myself from doing things so minimal and pop in the past. That made me think, 'Let's keep chipping away at the crack in the ice. We might fall through, but that prospect is exciting.'"

With the greatest-hits project shelved until 2014, the resulting, all-new Hesitation Marks (those two early tracks included) is both sonically singular and thematically linked to a particular scarred and multi-million-selling predecessor in the Nine Inch Nails catalog. "For some reason, when I started working more on Hesitation Marks, I started thinking back romantically about who I was when I was writing The Downward Spiral," Reznor says. "I was looking back on who I was then and who I am now and how things have turned out, for better or worse. That was the air the new record was born in. I was looking at the other side of how I was not always honest about who I was in the '90s — and I knew I wasn't being honest — and if you sprinkle those negative feelings with some drugs and alcohol, it's usually not a recipe for success."

Except that it was.

"Until the balance got thrown off," corrects Reznor, who successfully completed rehab for drug and alcohol addiction in 2001. "I'm happy with who I am now. I feel fortunate to be where I am. We tried arranging the new songs with loud guitars, and it sounded false. Instead, we approached those old emotions in new ways that are subtler, and I think just as powerful."

Adorned with art by Downward Spiral cover designer Russell Mills and heavily influenced by the spare, rhythmically complex feel of D'Angelo's Voodoo, the result is as sleek an album as Nine Inch Nails have ever made. Lead single "Came Back Haunted" squirms on the strength of a simple drum-machine pattern, scuffed synth wash, and sequenced bass; the laser-like "Everything" could be a lost Joy Division seven-inch, complete with a chorus wherein Reznor sings (not screams), "I have tried everything / I've survived everything." But instead of sounding like a furious regret, the line hits as hard-won wisdom.

"We tried not to do the classic Nine Inch Nail things on the album," says co-producer Alan Moulder, who has worked with Reznor going back to The Downward Spiral. "The old trademark with Trent was that when we got to the chorus, the songs go up a step, he sings in his highest range possible, and a million guitars come in. We tried to do the opposite on this one. The choruses actually go down; the sound is more withheld than explosive, which is a much harder thing to do."

The album is also a more insinuating, collaborative sound, a long way from the hermetic sonic phantasmagorias of 1992's landmark Broken EP or 1999's double-disc behemoth The Fragile. "In the past," says longtime NIN visual collaborator Rob Sheridan, "Trent would bring in a violin player and give him something very specific to do. This time, he'd bring in Lindsey Buckingham and say, 'Let's see what he'll come up with.' That's a radical change in approach."

[caption id="attachment_id_134340"]  AP Photo/John Gaps III[/caption]

AP Photo/John Gaps III[/caption]

For his part, Buckingham recalls there being a "great sense of calm in the studio. Trent's got this aggressive persona, but then he turns out to be this laid-back, soft-spoken guy putting things together in a very painterly way."

Reznor also enlisted former David Bowie and Talking Heads sideman Adrian Belew and D'Angelo studio bassist Pino Palladino, among others, for Hesitation Marks, and though things still aren't perfect — Belew has since bowed out of the NIN touring production, telling reporters, simply, "It didn't work" — the overall change in dynamics is still pronounced. "There's a lot less face-punching in the songs now," Reznor says. "I'm not as afraid of judgments as I used to be. I just want to do the best I can do, and not squander any more time than I already have when I was high. That's my main concern. If you don't like the music or think I should be someone I'm not, fine."

He juts his chin out defiantly. "But I'm still competitive," he says. "If I'm going to do this, I want to win."

[featuredStoryParallax id="97710" thumb="https://static.spin.com/files/130803-Nine-Inch-Nails-Lollapalooza03_1.jpg"]

Oversharing feels vulgar to me now. I know we've been fooled into thinking it's okay to show dick pics and that the Kardashians' behavior is normal, but it's not.

In the time between 2007's Year Zero (released on Interscope) and Hesitation Marks (released on Columbia), Trent Reznor hocked a lot of thick loogies in the direction of major labels. Publicly and repeatedly, he chided them for sticking their collective heads in the sand with regards to file-sharing. He thought that the suits were more inclined to sue fans than serve them. So he left."At Interscope, it felt like we were one of 50 bands, and we didn't sell as much as Eminem, so no one cared about us," Reznor says, having finished the coffee and moved on to the Diet Coke. "Combine that with unquestionably wrong move after wrong move in terms of the response to new technologies — I just felt like I could figure things out better than they could."

He was correct, up to a point. 2008's raw, jittery The Slip, offered for free on the NIN website, was downloaded 2.4 million times; a lavish, pricey physical package sold in the neighborhood of 250,000 copies. (That same year, he also offered the instrumental ambient collection Ghosts under his own Null Corporation umbrella.)

"Being in control of your own destiny was great," he says of the decision to go indie. "It felt good to have my own neck on the line. But you spend a lot of time figuring out who the influential blogger at some radio station is. Market research is not a sexy thing to think about. More than that, when you're self-releasing, you have this walled garden of people that are interested in what you do, and to everyone else you're invisible."

Meanwhile, as he sought to extend the boundaries of his fan base, he was reconsidering his role as a public figure.

"I was excited about Twitter when we went out on our own because it felt like the most direct way to penetrate people's attention," says Reznor, an early and eager adopter of the platform, who in his mid-aughts guise was quick to volley with fans and fire shots at fellow musicians. "I also got a charge out of people realizing that I wasn't a recluse sleeping in a coffin. But in hindsight, my experimenting with Twitter was a mistake. Oversharing feels vulgar to me now. I know we've been fooled into thinking it's okay to show dick pics and that the Kardashians' behavior is normal, but it's not. I've tuned out in the last couple years. Everybody's got a fucking opinion. It takes courage to put something out creatively into the world, and then to see it get trampled on by cunts? It's destructive."

There's another factor to Reznor's more cautious approach to social media: "I've had the experience over the last few years of liking bands, and then checking what they're up to on Tumblr or something, and immediately realizing, 'This is you?' Fuck.' I don't want my personality to get in the way of what I'm trying to do musically."

//player.vimeo.com/video/58637996

Once Reznor had sifted through the results of his various outreach trials, he decided he needed a hand. In November 2012, Columbia released An omen EP_ by How to Destroy Angels, his ambient-pop project with Maandig and Ross; that was followed up with a full-length, Welcome oblivion, earlier this year. "It was no meddling, a modest advance, we split any profits," he says. "If there used to be 100 people at a major working on a record, now there are 18, but they're the good ones. There's a lean, mean hunger. I'm not trying to be a major-label apologist, I'm just telling you what I saw. Instead of me and Rob Sheridan trying to figure things out, there's an extra 15 people and the sense that someone in France was aware of what we were doing — instead of us hoping we'd remembered that France existed. So when a Nine Inch Nails album was in the works, and the mission was to try to make as many people aware of it as we can, we thought, 'Let's try it. Let's see what happens.'" (Still, he adds that NIN's deal with Columbia is "not long-term.")

But given Reznor's willingness to call bullshit on the corporate overlords, was there any hesitance from said overlords to get into the Nine Inch Nails business?

"With an artist like Trent, you have to trust that they're making the decisions they want to make," says Columbia Records Chairman Rob Stringer. "He's been very smart about building up the demand for Nine Inch Nails by working on so many different things over the last few years — and the new record is so strong — that it feels like an opportunity for us to work with somebody who has an effect on pop culture. There was no trepidation on our part."

So far, so good. "Nine Inch Nails feels bigger than it ever has," says a bemused Reznor. "Is it because we're on Columbia? Is it scarcity? I don't know, but it doesn't feel bigger in the sense that we've desperately adopted some new clothing style. It feels organic, and it feels good not to be worrying about whether or not we shipped vinyl to the cool record store in Prague. I know that what we're doing flies in the face of the Kickstarter Amanda-Palmer-Start-a-Revolution thing, which is fine for her, but I'm not super-comfortable with the idea of Ziggy Stardust shaking his cup for scraps. I'm not saying offering things for free or pay-what-you-can is wrong. I'm saying my personal feeling is that my album's not a dime. It's not a buck. I made it as well as I could, and it costs 10 bucks, or go fuck yourself."

There's been a lot of change in the life of Nine Inch Nails, but also some constants. Twenty years and hundreds of performances down a crooked road, Trent Reznor still often chooses to say goodbye to his crowds with "Hurt," the last track on The Downward Spiral, and the song that in its lean, confessional intensity is Hesitation Marks' most direct emotional precursor."When I was younger, to hear people singing that song, or any song, back to me? Holy shit, what a great feeling," says Reznor, leaning forward. "Over time, that feeling corrupted me. I didn't feel interesting enough to deserve it, and then I reinvented myself as a caricature. Money creeps in, people want to sleep with you, you distort. Add alcohol and drugs, and things go south fast. A song like 'Hurt' is reinterpreted by who I am now — and I like that person a lot more.

"The person you're talking to now is the real me — the smart, together me from high school," Reznor continues. "I feel so much younger than I am. I wish I could change some things about the path it took to get here, but I feel lucky that I'm not as caught up in anger as I was."

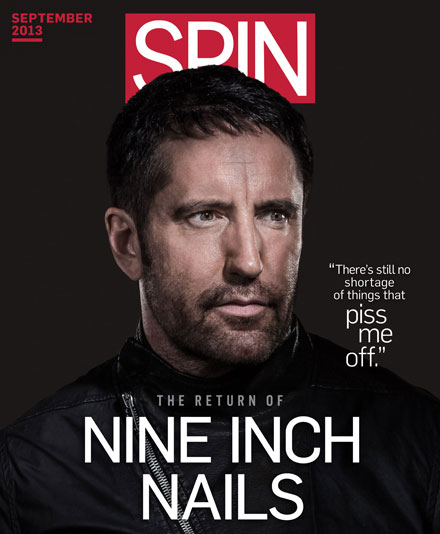

Then a sinister glimmer flashes across his hazel eyes, and Trent Reznor does what he's always done. "Believe me," he says, offering that old unsettling reassurance. "There's still no shortage of things that piss me off."