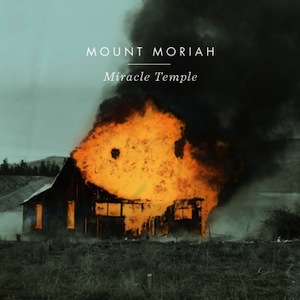

Release Date: February 26, 2013

Label: Merge

Like a lot of bands from the American South, Durham, North Carolina’s Mount Moriah sound voluntarily haunted by tradition. Their style is as traceable to Lynyrd Skynyrd as to Lucinda Williams, Southern artists who built careers by contradicting as many myths about where they came from as they embraced. Guitarist Jenks Miller recycles scraps from the Allmans’ playbook without the Allmans’ tumescent showmanship, and singer Heather McEntire sounds like nobody if not Dolly Parton, in whose tough yodels you can hear one of country music’s central paradoxes: showing how hurt you are by talking about how you’ll never ever get hurt again.

Despite their affiliation with Merge Records — home to Arcade Fire, Neutral Milk Hotel, Spoon, and a handful of other popular indie-rock bands — there is nothing indie-sounding about Mount Moriah. Their second album, Miracle Temple, sounds like music for people who think contemporary country is corny and inauthentic, indie-rock too vaguely metrosexual and disaffected, and the antiquarian high jinks of bands like Mumford and Sons too nightmarish to even register with the conscious mind. The guitars are amped to sound distressed, the drums are dry, the room is bare, and there is no audible trace of digital sound magic.

More than anything, though, the band’s spirit is an outgrowth of punk: They’re sparse and hard-bitten when they could stretch out, wry when they could be kind, and seem like they might elect to sleep on hard surfaces. To better understand Mount Moriah, it may help to have some familiarity of the North Carolina Research Triangle, where traditional Southern culture coexists both weirdly and inspiringly with progressive politics. When I lived in Chapel Hill, the anarchist bookstore was three blocks from a pricey Southern restaurant who ran a giant pig sculpture up a pole like a flag.

Nearly every moment on Miracle Temple takes place in the past. “You were always wild,” the opening line of “Younger Days” goes. “Show me where we been, where we started,” goes “Connecticut to Carolina.” In proper Southern fashion, the past for Mount Moriah is as alive as the present, and moreso when people in the present are drinking, which they seem to be doing constantly. Witness McEntire’s threat that “nothing will keep you from remembering,” or the hopeful promise that “that little girl is still alive inside me,” lines that treat what happened then as the primary force in shaping what’s happening now — or, to see where you landed as being mostly a factor of the place you jumped from.

This isn’t nostalgia because nostalgia actively wants to restore things to how they once were. Like good country, Miracle Temple is capable of painting a world where the past comes back in part because people aren’t really strong enough to keep it at bay. Their approach is the classic heal/wound/heal punctuated by trips to the social club and, when lucky, a misguided attempt to climb someone or another’s balcony. Or, in McEntire’s words, “Everybody knows you’ll always fall for the chase / Rookies and Beaujolais.”

It’s on the record’s bigger reckonings where the band most feels weighed down. “Miracle Temple Holiness,” “Telling the Hour,” “Union Street Bridge” are long and overly earnest, filled with vague words about darkness, light, mama, and whiskey — cliches of Southern songwriting that the album’s richer, more specific lines (about decorative plastic doves, Seven & Sevens, and tan lines) suggest without succumbing to. As in life, the serious moments are a letdown, and the supposedly less serious ones always seem to mean more as time goes on.

Yet for an album whose most apparent traits are simplicity and broadness, Miracle Temple‘s best moments are pretty idiosyncratic: The way Jenks steps into the spotlight on “Eureka Springs,” but so obviously avoids a big solo, the vaguely Eastern violins of “I Built a Town,” the choirs of “Rosemary,” and most of all, McEntire’s vocal performance, which at one point introduces the letter “Y” to the word “Connecticut.”

Whatever the lyric, whatever the stripped-down utility of the music, there’s always McEntire. “What is harm?” she sings on “Bright Light.” “Shalom, shalom / If darkness has you only bringing bruises into the light, let darkness take its toll and make it right, make it right.” What this cloud of abstraction is meant to mean Is anyone’s guess. The important thing is the animal sympathy of her voice, which flutters like a leaf loosed from a tree or a paper receipt falling toward the street from a 12th-story window, graceful even when subjected to the tyranny of gravity — which, as anyone who has ever felt held down by a small town knows, has a funny, bittersweet way of winning.