The Wu-Tang Clan introduced themselves to the world cloaked in a shroud of mystery. Claiming the hip-hop hinterland of Staten Island as their homeland, the gang of nine MCs bore kung-fu-inspired names and performed an assassin-like assault on the record industry. Their inaugural 12-inch, “Protect Ya Neck,” offered little evidence with cover art that involved only a black-and-white illustration of a book and a sword. When the oversized rap group’s debut album, Enter The Wu-Tang (36 Chambers), was released on November 9, 1993, it eschewed the chance to reveal the Clan’s faces, presenting six rappers clad in hoodies and masks. Rumors still abound as to what shenanigans were behind the incomplete cover roster.

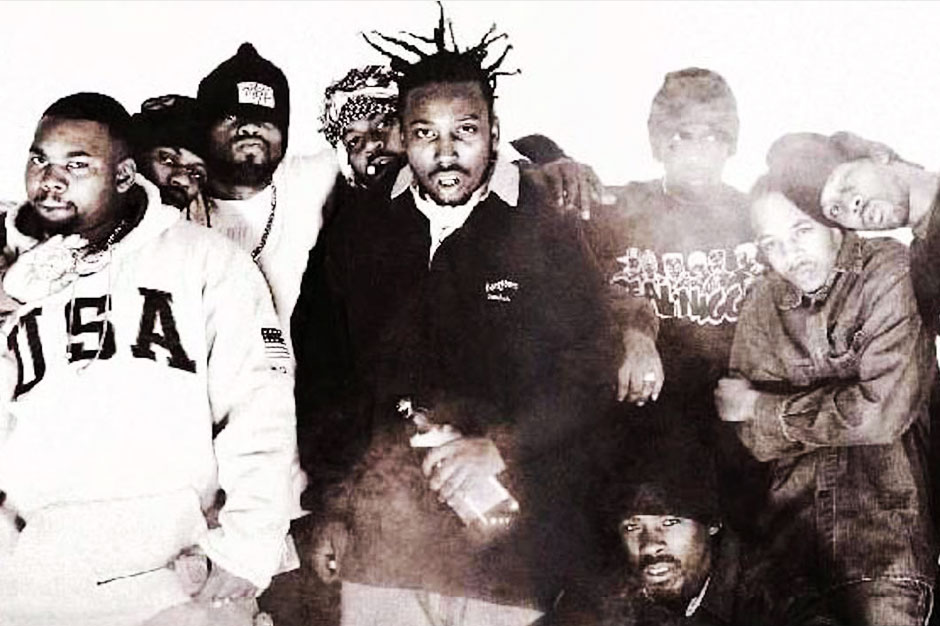

Twenty years later, the early mysticism that surrounded the Wu-Tang Clan has proved to be part of leader the RZA’s grand plan to turn scorned underground rappers into icons. It worked: The group’s nine members — including the departed Ol’ Dirty Bastard — are recognizable across the globe, grimy rap superstars from Shaolin lands. Though the Wu stepped out of the shadows and into the spotlight, there are less commonly credited music industry hands who were also involved in the group’s monumental breakthrough. We asked five of these unseen contributors to go back in the vault and reminisce over the time they helped bring the ruckus.

Yoram Vazan, co-owner of the Firehouse Studio: I met them before they were Wu-Tang, when [RZA and GZA] were Rakeem and Genius. My first impression was of Genius being an extremely talented rapper and very funny — he had lots of wit and was very bright and everybody was impressed with his rapping ability. Rakeem was of the softer kind of personality and a good vibe person. He was soft-spoken and waited his turn to do his rapping. It was a very nice family vibe.

Ethan Ryman, co-engineer: When we started recording Enter The Wu-Tang, the whole group was usually there for every session; sometimes it felt like their whole neighborhood was in the studio. Every now and then RZA and I would have to clear the room so we could get to the equipment. I remember feeling there was a very forceful energy with them. They were not playing around. They would bark orders at each other, not just saying something matter-of-factly but saying things with a tone of underlying “or else” — like everything was super important. It was badass and I started doing it too. It was like nobody wanted to show any weakness.

Also Read

GEAR THAT MADE THE GAME: Rap Machinery

Liz Fierro, art coordinator: Oh my goodness, what a cast of characters they were! First of all, we were so nervous about meeting them. They’ve got this mafioso rap persona, that’s for sure, but they were the nicest bunch of guys that I’ve ever had the pleasure of working with in the industry. We had a huge bus and we had to go to Staten Island to collect them all and find them all and we don’t know who’s who ’cause they’re all in hoodies and this and that. So like two of them were in McDonald’s getting breakfast and one’s over here by the pier. It was hysterical trying to get them all together. But we got them on the bus and then at the end of the day after the photo shoot, we dropped them all off in all these different locations like we were best friends. And Ol’ Dirty Bastard, he was like, “If you ever need anything, Liz, you know who to call.”

Vazan: The rest of them would say hi and give you a hug, but RZA would talk to me and tell me stories about how he’s moving on to become this aggressive rapper out of protest at the industry and at life.

Chris Gehringer, mastering engineer, the Hit Factory: RZA has a lot of things going on in his brain, you could tell that. You could watch and see him take charge.

Ryman: One of my fondest memories was seeing RZA explain to the group, who were not the moguls they are today — like Meth told me back then he was living like a viking, no hot water, no heat! — that he had turned down a million-dollar offer from RCA who were looking to sign the individual rappers, as well as the group. We all know how that turned out. A very smart dude.

Vazan: They played me “Protect Ya Neck” and it was very hard and incredible and it never stopped hitting you, you know? It was line after line, verse after verse, but when it got to ODB and it got to Method Man, it was like, “Wow, who are these guys?” The first time you heard ODB, it was amazing; it was like the Louis Armstrong of hip-hop with so much character in his voice, like he’s telling a story. ODB took you there into the text of his lyrics like a good storyteller, but also like a real actor.

Ryman: I can’t remember what jam we worked on first, and at that point, it might have even been a demo, but I remember Rakeem being smart and real cool and we got along well. Very shortly after that, the studio got a little bigger and moved to 38th Street in Manhattan and that is where I remember the first real Wu sessions beginning.

Vazan: We were in the midst of doing Masta Ace’s Sittin’ on Chrome and we moved out to Manhattan. It took us a week to re-set-up the studio so Ace could continue doing his work, and the next thing I know Wu-Tang came in. We planned to do four albums, but I remember RZA came in and said, “I got six albums to do with you.” It was Wu-Tang, Method Man, ODB, Gravediggaz, and I think he did two more at the same time. They couldn’t afford to pay, but RZA said, “Don’t worry, we’re gonna pay you back.” He was there for six months. They made Firehouse their home.

Ryman: I remember watching Genius wreck everyone at chess, and losing to him and RZA a few times myself, and playing cee-lo for dollar bills in the lounge. Cabs wouldn’t stop for RZA back then, so when we left for the night, I would go to Seventh Avenue to hail a cab for him back to Staten Island. The driver’s reaction to the switch was usually priceless.

Vazan: RZA always had a lot of thinking going on; he was the guy in the control room making his vision… I remember one day RZA comes in with a guitar and says, “I don’t play guitar, but we’re gonna get a few samples out of this instrument!” It was anything goes: Bring it in, we’ll sample it and we’ll use it. And I saw the evolution there. They used to come in with milk crates with the records and samples they wanted to use, then RZA comes in with his Ensoniq board, which was also a sequencer, and he actually recorded ODB into this machine. The recording was very crude because they know how to make beats, they don’t necessarily know how to record, and the sound was terrible but it was a technological revolution happening in front of my eyes. No more milk crates; these guys are coming in with the machines!

Gehringer: It was a little bit of a shit-show! It wasn’t the cleanest of audio, and it wasn’t audiophile material, and they didn’t spend a lot of time mic-ing and recording stuff, but sometimes art shows up in funny ways. I get that when people do stuff real grimy, and that record just seemed to work. I took that approach when I was working with it to maintain the dirt and the griminess, but at the same time, make it pump and kick and all that stuff. Most of the group were in for the album mastering and they kinda just said, “It is what it is.” They almost said — I think this is the quote — “We’re not like audiophile guys, we’re grimy niggas from Staten Island!”

Vazan: It was nothing different than what we did at the Firehouse at that time. They used to call it “basement flavor,” where it’s a low-budget studio doing hip-hop music that sells a hundred thousand copies. It was that early-’90s sound.

Gehringer: There were no real arguments from the group about the sound quality, but a lot of people at the label were like, “Okay, that’s it?” I was like, “Yeah, that’s what they gave me. It’s not going to really get any better sound-wise than that.” I think that’s what they were going for. The guys loved it, the label were kinda like, “Okay…”

Ryman: The final version of “Bring Da Ruckus” was not the original one we recorded. The first one had this blues sample that RCA couldn’t clear, so we re-recorded the sample and some of the other tracks. Other than that, the album that I bought in the store was the one we recorded.

Gehringer: Yeah, I’m not super proud of the overall output of the original mastering of it ’cause a lot of the mixes were not that great sounding, but as the album took off, every time they did a single, someone remixed it and it came out with a little better quality. I know the single version of “C.R.E.A.M.” sounded better than the album version.

Ryman: At the end of “C.R.E.A.M.,” when Meth is saying, “Dollar dollar bill y’all,” the last “Y’all” is pitched. That happened when RZA was laying down a sample of Meth doing the chorus, and while the tape was rolling, he rocked the pitch wheel on the sequencer to make that happen. That is some typical Wu-Tang creative fuck-you stuff.

Gehringer: We literally took a VHS machine and copied [the kung-fu samples] RZA wanted off the VHS machine and onto a DAT player and edited those pieces in… This was back in the days of pre-audio and computer workstations, so we were using digital editors that couldn’t cross-fade more than half a second and they had a lot of those skits that they had to slide in. It was probably more work putting that part of the album together than anything else.

Ryman: I remember there were probably ten or 15 skits and kung-fu pieces that never made it. We were literally cutting like five seconds here, two seconds there to put all these things together that the RZA wanted to make. He wanted to make a statement.

Fierro: The idea for [the album cover] was a collaborative effort. We had gotten a bunch of props — masks and hats and hoodies and candles and, actually, I still have the candles from the photo shoot. And there were some members who didn’t show up, so we decided to put masks on the members who were there. We also Vaselined the lens on [photographer] Daniel Hastings’ camera so it would give that effect of begin really eerie and so nothing would be sharp. They wanted the masks, as well, though. I don’t think we would have brought stockings on our own.

Jackie Murphy, art director: Daniel and I knew we had some missing members and we had these masks already as props. So because we had some absent members that day we put two of the managers in the shot. It helped that we had a clear vision of what the shots would be since the location was scouted and propped.

Fierro: We shot it at an old temple in Manhattan. I don’t think the building was condemned, but it looked a little condemned. We had them staggered ’cause there were steps, which was where the altar was; we had a couple of guys on each level. They were really great for taking direction. We were nervous about working with them, we didn’t know how they were going to be, and here’s two little white girls from Long Island directing them, but they were so cooperative. Right after the photoshoot, we had a music convention… and some of the members of the Wu-Tang Clan were there. I remember Ol’ Dirty Bastard was there and we were dancing with those guys all night long. He was doing some dirty dancing, that’s for sure!

Gehringer: My main memory of ODB was one time we had just finished a record and we were in the lobby of the Hit Factory; Poke and Tone [of the Trackmasters] had just pulled up with Destiny’s Child in their Jaguar. They walked into the lobby and were standing there waiting to go into the studio. ODB was like, “Yo, I’m ODB, Destiny’s Child, I got to spit on your record.” They literally all got back into the car and sat there! He harassed them!

Murphy: I remember having to call him from a pay phone at the Staten Island Ferry when he didn’t show up for the photo shoot. We were running out of quarters and we wouldn’t let anyone near the pay phone because we were waiting for return calls that we left on his answering machine.

Ryman: ODB was, I think, the first vocal we did — “Shame On A Nigga” maybe. He’s in the vocal room and I adjust the large boom mic over his head, give him his headphones and show him how to adjust the volume and where to stand. Then I go back to the control room to get the levels and make sure he’s comfortable with everything. So I’m looking at him through the glass and he’s kind of fidgeting and playing with his hands and looking nervous and I thought maybe he wasn’t used to being in the studio and was used to having a mic in his hand like on stage. So I push the talk-back button and say to him something like, “Yo, if you’re used to holding something, I can get you something to hold,” meaning I would get him a handheld mic if it would make him more comfortable. He starts laughing and shaking his head because he thinks I was telling him that if he was scared he could hold my dick! We got along well after that. He’s one of the wildest dudes I have met, but also a really intelligent, talented man.

Gehringer: One time he was at the Hit Factory and they were working on a Wu-Tang record there, and ODB literally said, “I’m going out to get a pack of cigarettes.” I heard the next day he calls from L.A. He just went to an airport and got on a plane.

Vazan: In all the years I’ve been doing music and making recordings, since ’81, you never know who’s going to make it. I knew Das-EFX were very special, but I had no idea they’d be that big. When Wu-Tang came, we knew the buzz was out, but we didn’t think it was going to sell, what, like five million? At one point, I just stopped keeping track. We didn’t know it was going to be a whole cult. They came out of the projects and were making music that became a worldwide revolution. I remember one day after the album [was released], RZA called me and said, “I just bought this mansion in Ohio. I’m moving out to a mansion.” It was beautiful.