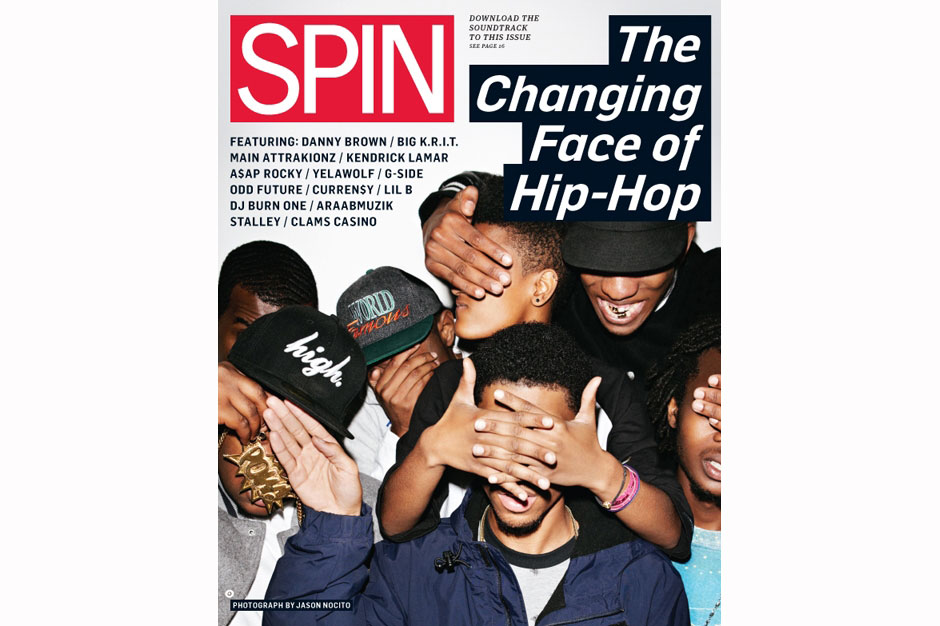

Goodbye, big-money bollocks and big-city trappings. Hello, tireless Internet hustlers taking their futures into their own hands. Welcome to hip-hop’s DIY moment.

More From SPIN’s December 2011 Issue:

• G-Side Launch a Hardscrabble, Regular-Dude Revolution

• Odd Future: The New Underground’s Loud Family Goes on the Road

• An Insanely Obsessive Infographic Tries (in Vain) to Diagram the Hip-Hop Galaxy

Rail-thin in skinny jeans and engulfed by a white T-shirt, one side of his hair shaved, the other long, straightened, and dangling in front of his face, Danny Brown steps to center stage. As a cluster of hard drums and groaning psychedelic guitars drops, he yells, “What?!”

Throwing up his arms and sticking out his tongue, Brown reveals a significant gap where his front teeth should be, then doles out high-fives to a mob of hip-hop heads, hipsters, and dance-music dorks. Finally, with a nervous yelp, he starts rapping: “Colder than them grits they fed slaves / Me to rap is like water to raves / AKs with bayonets on deck, rep my set?/ Sorta like Squidward and his clarinet / I’m in ya bitch mouth / But she just fantasizing / Staring at my skinnys, said they’re so tantalizing / Dog, I’m strategizing, plotting on the throne.”

Also Read

Trunk Muzik 4Ever

The performance is electric and unhinged — the good kind of unhinged. But quite a few at the party, thrown by tastemaking label Fool’s Gold, who released Brown’s fantastic new mixtape XXX, are confused by the rapper’s mix of sex punch lines, outré pop-culture references, and visceral flashbacks to a shitty upbringing in Detroit. And for some reason, a few are downright angry. For much of the day, lined up against the walls of the venue, groups of teenage boys, many shirtless, all smoking weed like doing so in public is actually transgressive, have treated the artists (Just Blaze, AraabMuzik, Fool’s Gold founders A-Trak and Nick Catchdubs) like they weren’t the reason everybody is gathered here on Labor Day.

Some of these kids start booing and one wanders through the crowd, waving his hands dismissively during Brown’s performance. Later on, it becomes clear that these budding hard-asses are there for A$AP Rocky, who performs later in the event’s “special guest” slot (earlier rumored to be Kanye West). Rocky is a hyped Harlem rapper ostensibly involved with the underground rap scene, but he feels like a mainstream throwback, clearly unprepared to perform, dropping names of upscale clothing brands (Rick Owens, Raf Simons) and brashly promoting himself off just two songs, “Purple Swag” and “Peso,” which, after moderately high YouTube traffic, have taken on the suspicious inevitability of industry-driven “hits.”

As a response to the surly teen contingent, Brown fearlessly moves in their direction. His eyes tighten, his flow focuses, and he delivers his lines right in their faces. A few months later, we speak over the phone while Brown’s on tour with Das Racist, and his voice raises to the excited octave in which he often raps as he recalls the situation. “That really bothered me, that fucked me up, there’s no way you can ignore something like that,” he says.

Danny Brown is perhaps hip-hop’s most fascinating new face, but that doesn’t mean he’s challenging Kanye or Jay-Z or Lil Wayne or Drake for pop notoriety or first-week sales numbers. It means that on the strength of a great album, er, mixtape, he tours decent clubs (or plays dodgy hipster parties), pops up on blogs and in magazines, and puts out the music he wants, when he wants, usually for free. It’s a modest vision of success, but for 2011’s burgeoning New Underground scene, it’s a familiar, even archetypal story — wandering around the industry for years looking for a reasonable major-label deal and then ultimately finding artistic freedom and an audience on the Internet. At different points in the 2000s, Brown talked to Roc-A-Fella and Def Jam, even recording an album with 50 Cent sidekick Tony Yayo, Hawaiian Snow, released on iTunes via G-Unit last year.

Various key figures in the New Underground scene are also refugees from the major-label system who finally said “fuck it” and jump-started their careers via the Internet (sometimes signing another deal after being dropped simply for a cash infusion, but still releasing mixtapes and touring with the knowledge that they’re mostly on their own). Guys like Mississippi’s Big K.R.I.T., thoughtful and conscious in the traditional ’90s sense, though just as apt to rap about “country shit”; New Orleans’ Curren$y, an uncharacteristically ambitious label vagabond with a soothing, stoner flow; Berkeley’s eccentrically prolific, mercurial viral wisp Lil B (formerly of the Pack); and Alabama’s Yelawolf, a hyperpoetic, white-trash MC who merges rap, rock, and metal in ways that won’t make you cringe.

Other New Undergrounders, savvy adopters of the ever-evolving ?Internet model, have flirted with labels of varying sizes but remain self-sustaining. Most notably, Odd Future, the Tumblr’ing collective from L.A. helmed by provocateur Tyler, the Creator; G-Side, a regular-guy duo from the insular yet worldly Huntsville, Alabama scene; Kendrick Lamar, the most visible member of Black Hippy, an eclectic West Coast group that includes Ab-Soul, Jay Rock, and Schoolboy Q; Cities Aviv, an arty loner from Memphis, previously ground zero for crunk; Oakland weedheads Main Attrakionz and their cottage industry of blissed-out “cloud rap”; Stalley, a revolutionary-minded, working-class car enthusiast who’s honed a style he calls “Intelligent Trunk Music”; and, literally, dozens more (Freddie Gibbs, Das Racist, Don Trip, Rittz, Fiend, Starlito, XV, Mr. Muthafuckin’ eXquire, Spaceghostpurrp, Action Bronson).

For years, hip-hop hype has been about which star rapper “co-signed” who and who was about to do this or that (a product of artists being buried on majors and never securing a legitimate release date). But the New ?Underground is happening right now. Rather than aggressively compete with or overtly reject the mainstream, this more independent scene (sometimes with a regional tinge, sometimes not) has exploded on its own terms, forging a genuine alternative network of interconnected rappers and producers, touring hip-hop and indie-rock clubs, hopping onto festival bills, and releasing a staggering amount of compelling music.

Since its emergence in the mid–late ’90s as an identifiable circuit and marketable subgenre — built by indie labels such as Fondle ‘Em, SoleSides, Raw Shack, Rawkus, Rhymesayers, Stones Throw, Definitive Jux, and Fat Beats — underground (or “indie”) hip-hop has been a loaded term. On an October episode of The Colbert Report, Mos Def and Talib Kweli appeared to perform as their late-’90s incarnation Black Star. Colbert asked them about the term “underground rap” and Mos Def joked, “Underground rap is a label we never understood. What does it mean? That we don’t rhyme above sea level?” That these two legendary MCs felt obligated to distance themselves from the scene they helped brand and keep creatively vital is telling of how the legacy of the underground has shifted.

To many, a decade later, underground hip-hop is now synonymous with “conscious rap” (or less loftily, “backpack rap”) and the mid-late ’90s era’s oppositional stance, often with an Afrocentric tint, where rappers tended to frame their rhetoric around what they weren’t (“gangsta”) rather than what they were. Still, underground hip-hop came about for a very specific reason.

For its first 20 years, hip-hop primarily had been an indie and underground culture, with occasional breakthroughs — Run-DMC and Beastie Boys in the mid-’80s, Hammer, Vanilla Ice, Dr. Dre, and Snoop Dogg in the early ’90s. But in the late ’90s, the genre became pop’s dominant force, via the Notorious B.I.G. and Puff Daddy, Tupac, Will Smith, DMX, the ?Fugees and Lauryn Hill, Jay-Z, Eminem, et al. Money was burned on hip-hop like never before, resulting in million-dollar videos and the promotion of a glamorized street lifestyle as the path to celebrity. Dan Charnas, author of The Big Payback: The History of the Business of Hip-Hop, describes the attitude of rap advocates at the time: “We blew down the doors of pop radio, then we blew down the doors of consumer products, then we blew down the doors in TV and film. Puffy’s out in the Hamptons! We’re in!”

In response, a more DIY underground scene sprung up. Some were more militant than others — Company Flow righteously declared they were ?”independent as fuck” — but all agreed that hip-hop should be more than Bad Boys strutting around in silly, shiny suits.

What went unacknowledged at the time was that hip-hop’s pop explosion, and the lavish imagery associated with it, was largely attributable to a speculative economic bubble (fueled by the Internet) that had Wall Street CEOs flaunting fleets of yachts and poppin’ bottles in strip clubs (sound familiar?). By extension, the arrival of mo-money-mo-problems largesse allowed underground rap to flourish. The dynamic even created its own superstar: Kanye West. As the “first nigga with a Benz and a backpack,” Kanye brought fun and splashy hooks into the college-kid-appealing underground and some sensitivity and moral seriousness to glossy, megapopular rap, collapsing the codified norms of both.

Meanwhile, another below-the-radar scene was gradually becoming a less didactic, rowdier alternative (though not hawking itself as such). Born out of early-’90s groups like the Geto Boys and the Underground Kingz (UGK), underground Southern rap simply became Southern rap by the late ’90s, thanks to labels like Cash Money, No Limit, and small grinding indies Rap-A-Lot, Hypnotized Minds, and Suave House. Despite inventing the word bling, Southern rap steered hip-hop toward something more workaday. Rappers like Juvenile fashioned themselves as guys on the corner who just happened to make it big — and that’s exactly what they were. The rims and grills of Houstonians and the crack rap of Young Jeezy and Clipse, which focused on the hustle’s nine-to-five aspects, lowered the stakes. Even the snap music of Soulja Boy, D4L, and others had a down-to-earth take on partying that wasn’t about VIP clubs. As the country tried to recover from the trauma of 9/11 and an early 2000s recession, Southern rap’s scrappy savvy and more methodical approach made the region hip-hop’s nexus.

The biggest Southern success of the 2000s was Lil Wayne, who permanently shifted the paradigm for how a rapper could look, sound, and comport himself, while still going pop. Wayne, already an above-average MC with a number of rap hits, became a superstar due to an endless stream of absurdist freestyles on mixtapes — quasi-official releases distributed through mom-and-pop stores. “I used to call them ‘street albums,’?” says Atlanta-based DJ Drama, host of the mixtape series Gangsta Grillz, who helped curate some of Wayne’s best material. Although Wayne had been mining the conventional mixtape format (freestyles over preexisting hits), Drama helped give his records “a concept” so they flowed naturally like albums. Wayne’s mixtapes started coming out more frequently and they kept getting better, an affront to the traditional industry, which refused to release anything without months of setup time.

During Wayne’s mixtape run in the mid-2000s, “the music industry really started to tank,” observes Dan Charnas. “It tanked in ways that really have nothing to do with hip-hop…because of the Internet.” With such easy digital options for creating and distributing music, major labels panicked — the ?focus on hits became ruthless; dependable rappers who’d once released a CD every few years to a devoted fan base became liabilities; release dates were delayed and artists held hostage until a hit single emerged. Few new voices were allowed to be heard, and mixtapes turned into a creative end run.

The flash point for the New Underground’s development came in January 2007 when the FBI raided DJ Drama’s office. All the mixtapes he was pressing up, recorded and sold in conjunction with the artists, and tacitly embraced by major labels as promotional tools, were seized. Like many ?actions instigated by the major labels’ bully pulpit, the Recording Industry Association of America, the mixtape offensive was a misguided response to pirating and bootlegging, which the RIAA believed had ruined record sales.

“After the raid, things really changed,” Drama recalls, still in awe of the sequence of events. “The actual physical mixtape CD never surfaced in the same way.” Lil Wayne’s Da Drought 3 was, instead, released for free online in the spring of 2007. “It was already going in that direction,” Drama says. “Around the same time as the raid, blogs and downloads became more prevalent to your average consumer.” Suddenly, anyone had access to mixtapes.

That’s where the New Underground really jumped off. Like the late-’90s underground, it was birthed out of industry vagaries — in this case, the ?absence of wealth rather than an abundance. The result was a new formula for a new type of success: practical underground idealism, plus Southern rap’s determined, indefatigable hustle, plus Kanye and Lil Wayne’s iconoclastic creativity. Or, as DJ Burn One, a key producer and curator of the scene, says, “Just put the shit out and see what the people feel.”

Yelawolf is a true original, a white skate-punk rap obsessive from the Deep South who could only exist in this very strange moment of transition. He’s taking advantage, simply calling his major-label deal with Interscope “an opportunity.” Signed to Columbia in 2007 and then dropped, he knows to taken nothing for granted. “The people at Columbia knew [signing me] was risky, but they didn’t know what to do with me. Then when Rick Rubin came in and brought his own team, that was it, man. He got rid of everything.”

Yelawolf worked with Burn One and producer Will Power on last year’s Trunk Muzik, a fully formed album given away for free. Based on the reception of Trunk Muzik, the Alabama rapper was signed to Interscope and the mixtape was re-released in stores last fall. Radioactive, his proper debut, is scheduled for release in November, with a rumored guest spot by Eminem, who is incorporating the younger rapper into his “Shady 2.0” crew.

Likewise, Danny Brown appreciates this specific moment. In the past, his obvious skills couldn’t make up for the fact that he is, and I mean this in the best way possible, a complete fucking weirdo. Now the whole package — high-pitched flow, fucked-up teeth and haircut, wonky ear for beats, broad knowledge of music outside hip-hop — is finally an asset. “In my head, I always felt like I was some big rap artist,” Brown says, laughing. “But every time I’d get around some type of label situation, it was always an image or marketing thing that I didn’t fit into or whatever.” He sounds more amused than frustrated. “So, after a while, I just wanted to do what I wanted to do.”

Brown’s XXX is one of the year’s most singular statements, as focused and well-constructed as any hip-hop classic. The record begins as an unadulterated party (weed, sex, Adderall), and then takes a dark turn, unveiling addiction, a death wish, and novelistic narratives about friends and family stuck in Detroit. The beats are minimal but rife with druggy effects, hinting at XXX‘s unlikely inspiration. “I was listening to Joy Division’s Closer,” he proclaims, as if that’s a totally normal influence for a rap album to have. Then again, with the New Underground, it isn’t that surprising.

Because little of this music is being sold, target audiences and copyright laws aren’t of much concern, so there’s room to experiment. For their space-age tracks, G-Side have swiped the slow-moving dynamics of post-rock, the open space of electronica, and unearthed emotive samples in what sounds like the music playing in a bummy Chinese food buffet. Cities Aviv’s Digital Lows is punctuated by experimental noise interludes. Main Attrakionz work with a web of producers all attempting to outdo one another with the most blissed-out, ethereal sounds. Along with producer Clams Casino, Lil B — a perpetual challenger of hip-hop norms — has intensified the pleasantries of New Age by slowing down samples and caking them with mood effects, ?establishing an eerie foundation for the New Underground sound.

Producers are pushing the boundaries the most, transcending hip-hop altogether. In the spring, Clams Casino casually put out a collection of his beats for Lil B, Main Attrakionz, and others, exposing them as haunting electronic instrumentals (and receiving a nod from Brian Eno). He’s also released an EP called Rainforest, and in August, at the PS1 Warm Up event in Queens, sponsored by the Museum of Modern Art, he blasted his slurry, moaning, feedback-drenched beats to a responsive crowd. Before the show, he excitedly told me how he’d had all his beats mastered to maximize their impact when they dripped out of the massive outdoor speakers.

AraabMuzik has gone from making beats like “Get It in Ohio” for Cam’ron to performing live on his MPC drum machine, pounding programmed samples into fist-pumping bursts of noise. This summer, he released a solo album called Electronic Dream, featuring his fractured take on trance music, and performed at the dance festival Electric Daisy Carnival. DJ Burn One’s group of live musicians, Five Points, put out a record called The Ashtray, which sounds like disco producer Giorgio Moroder and P-Funk guitarist Eddie ?Hazel locked in a room with a gang of weed. “Retro-future-type shit” is how Burn One describes the sounds on the album. Works for me.

Sincere traditionalists, long ago deemed niche artists, now have a home in the New Underground. “They wanna have fun, they wanna party,” says Big K.R.I.T., mocking the voice of A&Rs with the gall to insist what rap fans like him yearn to hear. Even his “party” track “Country Shit” was deemed “too regional” by execs. Rather than adjust his sound for a radio format, K.R.I.T. stuck it out, bridging politically charged material (“They Got US,” “Another Naive Individual Glorifying Greed and Encouraging Racism”) with loud, Dirty South bangers (“Just Touched Down,” “Sookie Now”).

K.R.I.T.’s Def Jam debut, Live From the Underground, has had its release date pushed from September to 2012, so he speaks of “staying on the road” and expects that his well-developed fan base will buy his album — whenever it drops. Meanwhile, he partnered with T.I. on the infectious “I’m Flexin’?” single. Crafting a solid collection of songs and touring go hand-in-hand, K.R.I.T. contends: “I have an entire body of music I could sell if I wanted to. I could do a whole show off it, and it wouldn’t sound like mixtape material.” For too long, touring was a reality most rappers skirted, but now they don’t have much of a choice. “You can’t download a live show,” quips Yelawolf. “It’s all that we have. It’s forced us to step it up.”

Though he’s been involved in recording Dr. Dre’s mythic, forever-delayed Detox, Compton’s Kendrick Lamar continues working on his own or with his wonderfully geeky Black Hippy crew, refusing to sit around smugly because he’s been tapped by a legend. His Section.80, released this summer, is an ?ambitious concept album about the lingering effects of Reaganomics, featuring “ADHD,” a flurry of Bone Thugs-ian syllables and beyond-stoned synths.

New Orleans rapper Curren$y, once signed to Cash Money and a frequent guest on some of those classic Weezy mixtapes, left the label after multiple delays of his debut. He raps almost exclusively about smoking weed, but he’s got an ornate ability to make it sound interesting every time by circling around to minor, telling details. There’s also a mature version of escapism in his music — he’s seen a lot, so he prefers to just kick back with a spliff and hone his craft. Between mixtapes, Curren$y has released proper albums: last year’s excellent Pilot Talk and Pilot Talk II on Def Jam; this year, Weekend at Burnie’s on Warner Bros. He seems to view labels as a place to get a loan and maybe some promo, just to maintain momentum.

The New Underground is even forcing the mainstream industry to ?adjust. At the MTV Video Music Awards this year, Tyler, the Creator received a Best New Artist award — his youthful appeal and charisma were too strong to ignore. The BET Awards’ “cypher” series, which placed a bunch of MCs on television and actually allowed them to rap, sprinkled in Big K.R.I.T., Kendrick Lamar, and Yelawolf, alongside Chris Brown, Eminem, and Rick Ross. Stalley even smuggled in some lines about police brutality.

That Rick Ross, perhaps the last unrepentant holdover of late-’90s decadence, has embraced an MC like Stalley as a member of his Maybach Music crew (along with former underground survivors Wale and Pill) is an interesting by-product of the New Underground’s emergence. Respected rappers are reaching down to align themselves with younger, less-established artists rather than the other way around. Diddy, Jay-Z, Snoop, Method Man, Nas, Waka Flocka Flame, Game, and Clipse’s Pusha T have sought out Tyler, the Creator for collaborations.

One rather pathetic example of this phenomenon was Three 6 Mafia’s Juicy J, who introduced A$AP Rocky in the “special guest” slot at the Fool’s Gold party, along with lo-fi Miami producer Spaceghostpurrp. As the two came onstage, the teenagers who’d booed Danny Brown rushed to the front, throwing elbows — which was particularly absurd because Juicy J, the former king of ’90s mosh rap, had been performing for about an hour and none of them seemed to care. The party emptied out because nobody else there knew who Rocky or Purrp were. The fact that they haphazardly rapped over their own prerecorded vocals didn’t help, either.

A few days later, A$AP Rocky was brought onstage by Drake at a Versace Fashion Week show. A live review of a Rocky show later that week reported that it was delayed by nearly two hours because the rapper was waiting for Drake to show up. Five weeks after Fool’s Gold Day Off, and one day after a New York Times profile, RCA Records welcomed Rocky to their label. He’s also set to join Kendrick Lamar as one of the opening acts on Drake’s next tour. His first release after signing with RCA, “Out of This World,” oddly sounded nothing like his previous tracks. Frankly, the A$AP Rocky narrative is a little too perfect, and his inexplicable rise flies in the face of the New Underground’s values.

Superficially mixing earlier Southern styles with Dipset bluster and a vague New Underground vibe to cop a just-edgy-enough context, Rocky is an anachronism du jour. Overblown pronouncements about his crew’s “movement” and his desire to be a business executive and style icon are pure ’90s delusion. The industry’s approach to the New Underground has been typical: Throw money at immature, blindly ambitious, buzzing artists — like Rocky or Kreayshawn, the white female rapper who signed to Columbia for a much-reported and yet-to-be-confirmed “million dollars” after her “Gucci Gucci” video blew up on YouTube — and then mold them into slightly reshaped versions of established stereotypes.

This is exactly why the New Underground’s ethos is based on measured self-sufficiency. Huntsville’s G-Side are the most poignant example of this ?approach. ST 2 Lettaz and Yung Clova rap to starry-eyed beats that soundtrack the unglamorous realizations that they no longer have to work day jobs and can travel outside the South. The group’s decisions are informed by a Harlem Renaissance-like devotion to the idea of independent, black ownership, as well as hip-hop’s longtime affection for DIY “out the trunk” distribution.

Touring most starkly illustrates much of this renewed focus on hard work and individual responsibility. “I’ve seen so many people play and it’s just…dudes rapping,” says Cities Aviv. “No feeling. I hate that kind of shit.” A few days after performing his first New York show at Brooklyn’s Glasslands, he was front and center for Danny Brown at Fool’s Gold. Cities Aviv speaks ?excitedly, like a fan first and a rapper second: “When I go to a show, I want to feel like, ‘This dude is gonna kick me in the fuckin’ face.’ If they let you down live, it’s to the point that you don’t want to listen to the record anymore.”

Given the influence the New Underground has already exerted on the industry, I float the theory to Danny Brown that this group of artists, and their way of doing business, could have a Nirvana-like effect on hip-hop. I certainly hope so. Rick Ross makes hot songs, but the whole shtick looks pretty ridiculous next to Brown’s ability to balance his X-rated chatter with raps about economic disparity or G-Side’s emotionally affecting sweep.

Brown doesn’t buy it. Like most of these guys, he’s too aware, too modest. “I don’t want it to be like some scene-type shit,” he explains. “[Nirvana] were trying to go pop and be commercial even though their whole gimmick was that they weren’t, you know?”

He stops, not wanting to speak for anybody but himself. “I just don’t think with us, it’s really like that.”