[This article was originally published in the August 2008 issue of SPIN. To coincide with the release of D’Angelo’s long-awaited third album, Black Messiah, we’re repromoting this feature, which looks at the singer’s post-Voodoo, pre-comeback struggles.]

On a Sunday in April 2006, Gary Harris pulled up to D’Angelo’s large starter mansion outside Richmond, Virginia, in a limo. Harris, the A&R man who’d first signed D’Angelo in the early ’90s and who had overseen his 1995 debut, Brown Sugar, was on a mission: to escort the singer to Eric Clapton’s Crossroads Treatment Centre in Antigua.

As he walked into the spacious kitchen, Harris knew this wouldn’t be easy. Spread across the kitchen table, marble countertops, shelves — nearly every available flat surface — were empty alcohol bottles of all conceivable varieties. “There was scotch, vodka, beer,” Harris recalls. “While I was waiting for him, he emptied the contents out of the corners of three or four bottles to get a shot.” D’Angelo himself was unshaven, about 40 pounds overweight, and hadn’t packed. “He was trying to act like he didn’t know I was coming that day,” Harris says.

According to Harris, it took more than five hours to corral D’Angelo into the limo. Then the real journey began. Four days after hooking up with him, Harris had only gotten the then-32-year-old D’Angelo as far as Puerto Rico, delayed by missed flights, a forgotten passport, and the singer’s insistence on emptying every hotel minibar he came across. After two days of trying to coax D’Angelo from his room at the Ritz-Carlton in San Juan, Harris threw up his hands.

“I told him he can do whatever he wants, but I’m getting on a plane,” Harris says. “D’Angelo broke down and cried,” and then agreed to go to Crossroads. The night he arrived, Harris says, “he called everyone he knew to send him a ticket to get him out of Antigua.” D’Angelo wasn’t in denial about his alcohol problem, Harris explains. “He just wasn’t prepared to deal with it.”

//www.youtube.com/embed/SxVNOnPyvIU

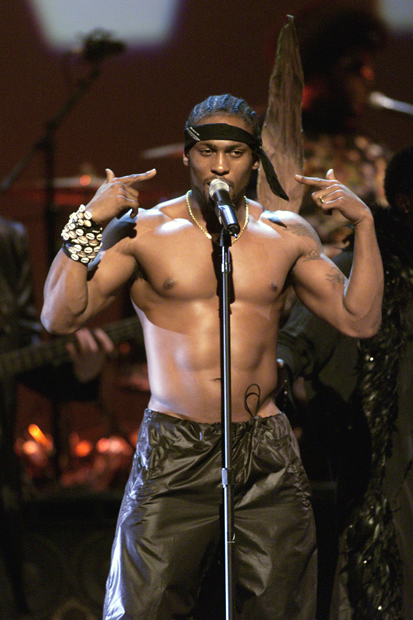

Six years earlier, a very different-looking D’Angelo stood on a small platform at a soundstage in New York City. His muscled frame was naked, save for a small gold crucifix on a chain, nestled in the valley between his pecs, and pajama bottoms hanging impossibly low on his chiseled hips, exposing the lower regions of a flat, V-shaped torso that pointed suggestively toward his crotch. The pj’s would be invisible in the “Untitled (How Does It Feel?)” video being shot that day. In it, the camera opens tight on D’Angelo’s head before drawing back slowly to reveal this once-chubby choirboy in all his sculpted glory. The effect is gloriously uncomfortable. As the camera sucks him in, it feels intimate and intrusive, revealing and voyeuristic.

“We made this video for women,” says Paul Hunter, who directed “Untitled” along with D’Angelo’s then-manager, Dominique Trenier. “The idea was, it would feel like he was one-on-one with whoever the woman was.”

The video was actually the second made for D’Angelo’s sophomore album, Voodoo. (The first, an artsy performance clip for “Left & Right,” stirred little interest.) It was part of Trenier’s strategy to shed the artist’s Brown Sugar-era image as a doughy 21-year-old kid sitting behind a piano. Although D’Angelo had been working out intensely with trainer Mark Jenkins, he was anxious about the video.

“Initially, to him, it seemed completely bonkers,” says Trenier, who managed D’Angelo from 1996 to 2005 and still considers him a close friend. “He didn’t quite get what I was saying. He kept going, ‘What do you mean, ‘naked’?”

Jenkins sensed D’Angelo’s reluctance: “You’ve got to realize, he’d never looked like that before in his life. To be somebody who was so introverted, and then, in a matter of three or four months, to be so ripped — everything was happening so quickly.”

Nonetheless, the video was a massive hit, introducing D’Angelo as a rippling Adonis to a new audience and driving Voodoo‘s sales well past a million. In the process, it also came to define the album and, to a certain extent, D’Angelo himself.

“I feel really guilty, because that was never the intention,” Trenier says. ” ‘Untitled’ wasn’t supposed to be his mission statement for Voodoo. I’m glad the video did what it did, but he and I were both disappointed because, to this day, in the general populace’s memory, he’s the naked dude.”

D’Angelo hasn’t offered much to replace that image in the public’s mind since then. Eight and a half years after Voodoo‘s release, a follow-up remains little more than a rumor. He’s done no interviews since 2000 and refused repeated requests to talk for this story. A just-released greatest-hits package features him shirtless on the cover. Apart from scattered cameos on tracks by Common, Raphael Saadiq, and Snoop Dogg, D’Angelo’s only real public appearances have been in court to answer charges of drunken driving, drug possession, assault, and disturbing the peace, among others.

“I feel like there’s a book with a bookmark in it,” says Trenier. “Two albums? That can’t be it for this guy. He’s got so much music in him.”

//www.youtube.com/embed/eT75hdcOOkU

Voodoo‘s impact is hard to overstate. Brown Sugar had kick-started the neo-soul movement in the mid-’90s, opening the door for artists such as Erykah Badu, Maxwell, Lauryn Hill, and Jill Scott. But Brown Sugar, while undeniably intoxicating, had relatively narrow ambitions: It was an ode to weed and women, whose organic, throwback grooves owed more to the progressive mind-set of late-’80s/early ’90s Native Tongues hip-hop than to the slick, digitized R&B of the day made by Boyz II Men and Keith Sweat. The ingredient largely missing was pain. If great soul music is defined by struggle — be it political, personal, cultural, spiritual, or carnal — Brown Sugar generally lacked the ache necessary to qualify. Only “Shit, Damn, Motherfucker,” a Stevie Wonder-style fink creeper about infidelity and bloody revenge, hinted at what was in store.

Voodoo evolved from more than three years’ worth of sessions, mainly at New York City’s Electric Lady Studios. An impressive roster of soul, funk, and jazz players were brought into, in Trenier’s words, “spar with the champ.” Notable among these were Roots drummer Ahmir “?uestlove” Thompson, who became D’Angelo’s musical copilot, keyboardist James Poyser, guitarist Charlie Hunter, and trumpeter Roy Hargrove.

“What was cool about it,” Thompson remembers, “was D had the A room [of the studio] on lockdown, and Common had the B room. Then Common brought [producer] Jay Dee inside, and next thing you know, both camps are working in each other’s studio.” Others like Badu, Talib Kweli, and Mos Def visited frequently, creating a ground zero for what Thompson called “a left-of-center” black music renaissance.”

As Common puts it: “It was one of those time periods that you don’t even realize when you’re going through it that it’s powerful. What came out of that period was Voodoo, [Common’s] Like Water For Chocolate, [Badu’s] Mama’s Gun, and [the Root’s] Things Fall Apart.”

Voodoo itself seemed to spring up from the ether. The historical reference points — Marvin Gaye, Curtis Mayfield, Miles Davis, Prince — breathe organically from the album’s dark grimy funk. If Brown Sugar was the sound of a bright-eyed young man flush with love’s first blush, Voodoo tracks such as “Left & Right” and “The Root” suggest a guy who’s seen love’s nasty side, for better (“Smack yo’ ass, pull yo’ hair / Even kiss you way down there”) and worse (“My blood is cold and I can’t feel my legs”). “Devil’s Pie,” the album’s centerpiece, is a sweaty, head-nodding sermon against the evil seduction of hip-hop materialism.

Following the album’s release, D’Angelo put together a crack touring band called the Soultronics that included some of the Voodoo crew (with Thompson as the musical director), then hit the road with a startling three-hour nightly extravaganza that ran for eight months. Tour manager Alan Leeds, who previously helmed James Brown’s classic late’60s/early-’70s outings and Prince’s Purple Rain tour, calls the Voodoo run his most memorable. During these frenzied live shows, D’Angelo’s songs grew into entirely new animals, and the singer himself into an electrifying, charismatic frontman. But for those who’d discovered him via the “Untitled” video, that wasn’t necessarily what they came to see and hear.

“We couldn’t get through one song before women would start to scream for him to take off something,” says Hargrove. “It wasn’t about the music. All they wanted him to do was take off his clothes.”

The catcalls had an undeniable effect on D’Angelo. “He’d get angry and start breaking shit,” Thompson remembers. “The audience thinking, ‘Fuck your art, I wanna see your ass!’ made him angry.”

For D’Angelo, who, as Trenier puts it, “isn’t a sexy dude” but a “real musician who wears glasses and plays video games,” the objectification appeared to do lasting damage.

“I didn’t realize how vulnerable he was and how deep his issues ran,” says Leeds. “He’s cursed now with fretting over how much of his fan base is because of how he looked as opposed to the music. It took away his confidence, because he’s not convinced why any given fan is supporting him.”

D’Angelo, born Michael Eugene Archer, the son of a Pentecostal preacher, also struggled, like Marvin Gaye and Al Green before him, to reconcile his sexed-up musical persona with deeply embedded religious convictions. “The whole idea that you’d sold your soul because you’re playing devil’s music instead of playing in the church,” says Leeds, “that’s very much part of his issues deep down.”

Nonetheless, when the tour ended in late 2000, there were ambitious plans that included a live album, a Soultronics studio album, and a new D’Angelo full-length in relatively short order. Leeds, who by this time was co-managing along with Trenier, recalls, “The whole industry was saying, ‘This next album will turn you into a superstar. The table is set.'”

//www.youtube.com/embed/fce41OOpUPk

But things didn’t go as planned. Initially, D’Angelo took time off and returned to Virginia. Then, in April 2001, Fred Jordan, a close friend of D’Angelo’s who worked at MTV, killed himself, which reportedly left the singer reeling. “We weren’t even thinking about making a record,” Trenier says. The hopes for the live album and the Soultronics project fizzled.

Eventually, D’Angelo did begin working, mostly in New York and at a home studio in Richmond. Sessions proceeded in fits and starts for the better part of two years. “It was a slow process,” says Leeds. “He’s the kind of guy who will book the studio and then come in, not feel inspired, and play video games for three hours with the meter running.”

According to Russ Elevado, who’s been D’Angelo’s recording engineer and close friend since they first hooked up midway through the Brown Sugar sessions, there were other forces as work, too.

“He started getting really involved with alcohol, which led to other things,” Elevado says. “It was horrible to see him that way, but there was no talking to him. I tried, and then big stars like Eric Clapton were trying to talk to him. He was very hard to work with.”

Through it all and in sharp contrast to the Voodoo sessions’ communal vibe, D’Angelo was working mostly alone, trying to play every instrument himself, while Elevado worked the board.

“That’s partly the reason it’s been taking so long,” says Elevado. “The deeper he got into the drinking, he was embarrassed for people to see him in that state.” And although D’Angelo was showered with praise for Voodoo, a significant amount of the credit publicly went to his collaborators, particularly Thompson. “There’s an element of D just wanting this album for himself. There are egos involved. Maybe once he feels he’s expressed himself enough, he can get other musicians in.”

“D’Angelo’s goal,” Leeds adds, “was to record like Prince: complete creative control. ‘I don’t even want the label to hear this until it’s absolutely finished.'”

Unsurprisingly, this didn’t sit well with Virgin, his label. Jason Jackson, Virgin’s head of urban music from 2001 to 2004 (and Lauryn Hill’s ex-manager) felt caught in the middle. “From a label’s perspective, they wanted an album and wanted an album immediately. So they began to apply a lot of pressure — ‘When’s it coming?’ ‘We need it now!’ — that kind of thing. D’s camp didn’t respond well to that.”

Virgin itself was in a state of flux. With new ownership, many staff members and executives were being let go, making the label all the more anxious to bring out a profitable record it had already sunk well over a million dollars into.

“There were probably endless hous’, days’, weeks’, months’ worth of music, but we never got a sense of when that album would come,” says Ray Cooper, Virgin’s co-president from 1997 to 2002. “We were always being told he was ‘hitting a great creative streak’ or ‘nearly finished,’ only to see nothing. It just became you’d be thankful if he was back in the studio working on something.”

He was working. Those who’ve heard the music, while cautioning that it’s all unfinished, generally rave about it. Apparently, D’Angelo had been playing a lot of guitar, lending tunes a distinctly rock edge. “the best way to describe it would be a Parliament/Funkadelic meets the Beatles meets Prince,” says Elevado, “and the whole time there’s this Jimi Hendrix energy.”

“He was determined not to make a record like Voodoo,” Leeds says. “He wanted to make some kind of different record, so he was trying to let the music flow and see where it took him.”

Whatever progress being made halted around late 2004, as D’Angelo’s drinking escalated and Virgin lost its patience and cut off funding. For roughly a year and a half, little if any recording was done. In January 2005, D’Angelo was arrested in Richmond and charged with disturbing the peace, possession of Marijuana, carrying a concealed weapon, driving while under the influence, and driving without a license.

“After, there was a really not-flattering mug shot that came out,” says Trenier, who’d moved to Los Angeles by this time. “I was like, ‘Nah, this cannot be my man.’ I borrowed a tour bus and picked him up in Richmond.”

After D’Angelo’s first rehab stint in L.A., Trenier set up meetings with J Records honcho Clive Davis and Interscope head Jimmy Iovine, both of whom reportedly flipped when they heard the music. A new deal with J was in the offing, but then, in September 2005, a drunken D’Angelo crashed his Hummer in Virginia, landing him in the hospital. According to several sources, the J deal was then pulled off the table, and in the coming months, D’Angelo split with Trenier and Leeds and, by most accounts, alienated nearly everyone close to him.

“His girlfriend had left him, his attorney had had enough of him, the babies’ mothers and most of his family weren’t really in touch with him,” says Harris. “He’d basically hit rock bottom.”

Harris helped hook D’Angelo up with Irving Azoff, a high-powered manager, who in turn bankrolled his Crossroads trip. But after that rehab attempt, according to Harris, it took five months to get a meeting with Jermiane Dupri, then Virgin’s head of urban music, to discuss D’Angelo’s future. During that time, the singer recorded cameos for Common and Snoop records, but mostly hung out in Virginia and started boozing again. Early last year, Thompson leaked an unfinished D’Angelo tune called “Really Love” to an Australian radio station, fracturing their relationship. While they’ve since patched things up, Thompson has continued to keep his old friend at arm’s length.

“It’s a fear thing on my end,” he says, sighing deeply. “I’m afraid that I’ll lose him. If I’m there and I lose him, I’ll have those feelings of guilt, like, ‘What could I have done to save him?'”

//www.youtube.com/embed/H_WzjiTzZBA

While D’Angelo grew increasingly isolated, the rocky path he was traveling was, ironically enough, quite crowded with like-minded compatriots. At least three of neo-soul’s other late-’90s leading lights — Maxwell, Badu, and Hill — have spent much of the new millennium on the sidelines. Hill’s struggles have been well documented: She followed her 1998 breakthrough, The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill, with an MTV Unplugged set four years later that felt like the soundtrack to a real-time nervous breakdown. She’s yet to offer a second studio album and, apart from some aborted Fugees reunions, occasional shows, and involvement with a shady guru, much of her time has apparently been devoted to her family.

Badu released her triple-platinum debut, Baduizm, in 1997 and successful follow-up, Mama’s Gun, three years later, and then said she had writer’s block and went out on what she dubbed “The Frustrated Artist Tour” in search of inspiration. She eked out a slight EP in 2003 but was then largely silent, until the well-received release of New AmErykah (Pt. 1: 4th World War) last February.

Maxwell’s journey probably parallels D’Angelo’s most closely. The Brooklyn-born singer released three platinum albums between 1996 and 2001, earning frequent comparisons to D’Angelo, then seemed to disappear entirely. A new album, Black Summer’s Night, was originally slated for spring 2004 but has been delayed repeatedly. Some close to him suggest that, like D’Angelo, he’s been wrestling with a rather ill-fitting public image as a sex god. His label says he’s still working on his new album, but there’s no release date slated.

In the case of all these artists, the repeated delays and disappearances can’t be entirely attributed to personal issues. “It’s no coincidence it’s going to take ten years for the next D’Angelo record to come out, ten years for Lauryn,” says Thompson. “It took Erykah eight years, probably the same for Maxwell. You could say the same for Black Star and OutKast. You could go further and say the same for Dave Chappelle. A lot of factors have played into stalling the left-of-center black movement.”

One is quality control. “These artists won’t allow anything they believe is subpar to be out there,” says Common. “I can hear stuff D’Angelo did messing around in the studio and think it’s incredible, but if he doesn’t feel it, fans aren’t going to hear it. Same thing for Lauryn or Erykah.”

Kedar Massenburg, who managed D’Angelo early in his career and first signed Badu, and who is credited with coining the term neo-soul, says the pressure on these artists to constantly innovate can get paralyzing. “they always want to come with something different,” he says. “They rarely respect other stuff out there or listen to other things because they’re trying to contemplate ‘going to the next level.'”

According to Thompson, this perfectionism is complicated by the fact that these artists work mostly by themselves. “The one thing I kept telling Erykah was, ‘You can’t do it alone,'” he says. “When you work alone, you don’t have the judgement of others; that’s when you start second-guessing yourself and holding your things hostage. Then, some people have a ‘yes man’ factor.”

This has been a particular problem for D’Angelo. ‘Not a lot of people are willing to say no to him,” says Elevado. “He gets in the way all the time. I don’t want to say he’s manipulative; he just has a way of persuading people.”

Additionally, the neo-soul tag itself became problematic. As Leeds explains, the movement had “built-in obsolescence, because it was so associated with the heritage of the music,” which stifled excessive experimentation. “In some ways that became a trap: If you got too progressive, you’re not being true to your roots.”

In turn, there’s an additional burden to balance these creative pressures with the desire not to step so far off the reservation musically that their art will tank at the sales counter. In Voodoo‘s liner notes, African American poet/recording artist Saul Williams writes presciently about the tug-of-war between art and commerce in black culture (spoiler alert: art is losing). He contends that has put even more weight on the shoulders of D’Angelo and his ilk.

“When our generation falls victim to that Diddy mentality of ‘Get money by any means necessary,’ that puts a disproportionate amount of focus on people like D’Angelo and Lauryn,” he says. “It’s like, ‘You’re the only ones that get it. you guys have to cut through the bullshit.’ So then we’re like, ‘You’re not just a great artist, you’re the messiah! Please come out with something!’ It’s enough to drive you batty.”

While most of these artists never viewed music as a path to fame and riches, Thompson maintains that it’s not hard to subconsciously internalize those commercial pressures. “I live with that,” he says. “When I create things, I almost have to dumb it down a little, because low record sales for me is seen like a failure…Black product is only celebrated when the artist’s image is overbloated, overanimated, and there’s sales to back it up.” This isn’t necessarily clear-cut racism, he says, but rather something the black community bears some responsibility for fostering. “the new minstrel movement in hip-hop doesn’t allow the audience to believe the artists is smart,” he continues. “I love Kid A, but I don’t think D’Angelo would be allowed to sing ‘Cut the kids in half’ over and over and be taken seriously. It’d be like, ‘What’s wrong with that boy?'”

//www.youtube.com/embed/YBB8valskCQ

Nearly everyone interviewed for this story agrees D’Angelo is in pretty good shape these days. After a few setbacks, sobriety seems, for the moment anyway, to have stuck. He returned to the studio in earnest around late 2006 and has recorded at a reasonably consistent if not exactly breakneck pace since. There is, however, disagreement on how close he is to actually finishing his album.

After protracted negotiations, J Records finally inked him to a new record deal last December. Tha label hopes he’ll have an album on the shelves by the fall or winter, and his new manager, Lindsay Guion, says he’s on track to finish recording by the end of August. While no one disputes the quantity or even the quality of recording that’s been done, Elevado, who has been part of nearly every D’Angelo recording session since Voodoo, says that, as of late May, the number of songs actually competed stands at zero.

“Six songs are very close,” he says. “Just a couple of lyrics, a couple of overdubs, and they’ll be ready for mixing.” The latest sessions have gone well, Elevado says, “but not as productive as I’d like and nowhere near the Voodoo times. He’s still taking a lot of breaks. He’ll come in and not do a lot. His energy is better, but I don’t know where his focus is.”

As of early June, D’Angelo was in Virginia taking time off. He’d been recording out near San Francisco in March but returned home shortly after the death of Chalmers “Spanky” Alford, the guitarist on the Voodoo tour. “That hit him pretty hard,” says Elevado. But more recording is planned for later in June, and sessions are planned with Saadiq, John Mayer, and Cee-Lo.

Whatever form the album takes, questions remain as to which D’Angelo will promote it. What if he looks more like the pudgy Brown Sugar kid than the chiseled Voodoo hunk?

Peter Edge, D’Angelo’s A&R man at J, Doesn’t think that particular scenario is likely. “I’m not saying he’s going to be doing the ‘Untitled’ video again, but he’s into martial arts these days and very much back in shape.” Despite D’Angelo’s troubled history, Edge has high hopes. “I want him to be a big, universal superstar who could transcend genre and appeal to everyone. He’s that good.”

//www.youtube.com/embed/HPp6pTrNw44

The question, though, is whether D’Angelo wants that himself. Trenier, for one, isn’t so sure. “He’s a throwback in that he’s like, ‘Why can’t I just put the music out? If I want to tour, cool, but I don’t want to go on MTV and shake hands with Carson Daly.'”

In some ways, choosing material, collaborators, and a marketing plan are just details, and all the talk of self-image, art, commerce, and inspiration are simply justifications for an artist who has been stuck in what Saul Williams calls his “prince of Denmark phase” for too long.

“A lot of it is just letting go and telling himself, ‘I’m not going to add another thing,'” says Elevado.

Trenier agrees: “Don’t feel sorry for him, because it ain’t that. It’s on him to change and go, ‘I’m ready.'”

In fact, nearly all those close to him concur that at this point, the only thing keeping D’Angelo from finishing this album is D’Angelo. Thompson says it all comes down to something those in his and D’Angelo’s circle call the “Latifah factor.”

“The Latifah factor is that last scene in Set It Off, where she’s like ‘Fuck it. If I’m going to get the shot, I’m going to get shot with my chin sticking out,'” he explains. “She gets out of the car and gets blown the fuck away.

“That’s a rather morbid view of it,” Thompson continues with a laugh, “but really, I think D will be pleasantly surprised. He just needs to stop tripping over his feet and make the record already.”