It’s a hallucinatory 110 degrees in a parking lot in the Los Angeles neighborhood of Glendale, where Brian Reitzell stands outside of a nondescript recording studio located amid a strip of office spaces, recounting his apocalyptic first recording session here. “I had been at work all day on 30 Days of Night, my first horror film soundtrack and the first thing I worked on in my new studio,” says the drummer/composer/music supervisor, pointing with a lit American Spirit to nearby Griffith Park, looming in the distance. “It was a scene in the film where this whole town is on fire. And I walked outside and that whole hill right there was ablaze.”

Most days, Reitzell has little chance even to feel the Californian sun, putting in long hours that make him one of the most in-demand composers and music supervisors in town. His current run of projects illustrates his range. One is his score for the eagerly anticipated video game Watch Dogs, which was UbiSoft’s highest-grossing game in its first week of release (a vinyl version of the soundtrack will be released by Portishead’s Geoff Barrow on his Invada label). The second is the second season of NBC’s Hannibal, for which Reitzell provided 43 minutes of original music each week — after 13 episodes, that’s over nine hours of nerve-melting scoring for the psycho(tic)drama. And the third is Auto Music, his first solo album in over 20 years of music-making, featuring guest turns from the likes of My Bloody Valentine’s Kevin Shields and My Morning Jacket’s Jim James. For an artist accustomed to spending most of his time behind the scenes, this last one feels especially significant, even though Reitzell says, “To me, Auto Music wasn’t work. It was in-between work.” Take that with a grain of salt, perhaps, given that he says he spent two weeks getting just the tremolo right on one song.

Along the way, in a career that has encompassed punk, ’90s alternative rock, film, and television, Reitzell has earned a reputation for coaxing even the most reluctant collaborators out of hiding. Since his soundtrack for 2003’s Lost in Translation, Reitzell has gotten Shields, Elliott Smith, Mark Hollis, and Richard D. James (a.k.a. Aphex Twin) to contribute music to his various film and television projects, even after these men have spent years — in the cases of Shields and Hollis, more than a decade — in silence. On 2013’s The Bling Ring, his most recent soundtrack for close friend and director Sofia Coppola, Reitzell wound up getting both the recalcitrant Kanye West and Frank Ocean to license their blockbuster music to the small indie film, for a budget that was estimated at a mere $15 million. What is it about this 48-year-old former drummer that gets difficult artists to say yes?

Today is a rare day off for the workaholic Reitzell. Dressed in a T-shirt, slacks, and canvas shoes that are three variations of slate blue, he has just finished mixing the last episode of Hannibal earlier in the week. “Each episode is named after a Japanese food course, so I indulged my love of Japanese films and music,” Reitzell says, pulling out a book on Japanese composer Toru Takemitsu, famous for his scores to art-house films like Woman of the Dunes and Akira Kurosawa’s samurai epics.

He has a drummer’s slouch and wears black-framed glasses with thick lenses; his hair is tucked behind his ears. Reitzell takes a tiny mallet in hand, pulling out a heavy black box and setting it on a floor tom in the live room. An eerie, resonant tone fills the room as he plays the handmade slit drum.

“One night I was watching a documentary on Toru Takemitsu and there was a shot of a guy playing what looked like a bronze slit drum on top of a tympani,” he says. “I took a screen shot with my phone and emailed a guy who makes slit drums and asked if he could make me something like that.” It took over a year to get the bronze instruments forged, each box weighing over 30 pounds. But the long, tortuous process was well worth it, he says. “It wasn’t cheap or easy, but it really paid off. Its exotic timbre sits so well inside the Hannibal score.”

He cues up a scene from Hannibal, wherein the anti-hero is preparing a meal when Laurence Fishburne’s character Jack Crawford confronts him. “The second season started out with a fight between Hannibal Lecter and Jack Crawford and then cuts to 12 weeks earlier. By the final episode, the audience knows the fight happens. I used my kitchen timer and wound it up and built on top of that tempo for the entire episode.” He cues the scene, the metronome slowly turning frantic until it explodes into a cacophony of bells and alarms, as both men hack at one another with Ginsu knives. It’s a frightening, heart-bursting scene, but on another level, it’s a masterful display of Reitzell’s musical sleight-of-hand: He has managed to sneak Japanese avant-garde noise into American prime-time television.

Reitzell was born in Northern California, and he grew up in Ukiah, north of San Francisco. His father was a muscle car guy who took his son to drag races. “We saw Big Daddy Don Garlits, Snake, and Mongoose,” he says. “My dad had a candy-apple red sparkle drag boat with a giant hemi engine in it that he raced professionally. The sound of that engine was the most incredible sound ever. To this day, nothing could top it.”

His parents split when he was five, and Reitzell went to live with his mother in a commune in Redwood City, where Hell’s Angels members became his adoptive uncles and the Rolling Stones’ Goat’s Head Soup played all day long. He became infatuated with the drums via his uncle’s gold sparkle Ludwig drum kit, which was festooned with Christmas lights. “We would turn those lights on and I would sit at the drums. I was five and couldn’t reach the pedals, but that made me want to play drums,” he said. Even his uncle’s attempts to dissuade his nephews from messing with his stuff fueled Reitzell’s drum fever. “My uncle would always hide the drum sticks so my brother and I would go into the kitchen and get wooden spoons, wire whisks, whatever we could use to play. Which I still do today.”

He moved to San Francisco at 19 and began playing with the band Wire Train while also apprenticing as a chef. “I officially became a chef the day after the big SF earthquake in 1989,” he says. “In fact, I was driving across the Bay Bridge on the bottom level just past the chunk that fell!”

Eight months later, he auditioned and became the drummer for Redd Kross, the punk-turned-glam band who were the odd men out in the era of ’90s grunge. “It was a wonderful time, because that era of grunge meant I had friends in the Top Ten,” he says. While touring for Redd Kross’s 1993 album Phaseshifter, Reitzell became disillusioned with the band, and the touring grind, and quit. But he remained close with his former bandmate Steve MacDonald’s ex-girlfriend Sofia Coppola, who was friends with Reitzell’s girlfriend (now wife). He would make mixtapes for Coppola and when in San Francisco, they would get together for dinner parties. “Brian would make these pasta dishes and we’d listen to music together,” says Coppola, via email. “He made me great ambient mixes with Brian Eno and Ashra Tempel. We were so in sync on music that when I started working on The Virgin Suicides in 1999, I asked him to help me pick some songs of that period.”

Daniel Lopatin, who records as Oneohtrix Point Never and worked with Reitzell on 2013’s soundtrack for The Bling Ring, recalls that film fondly. “I was definitely aware of Brian mostly because of The Virgin Suicides soundtrack,” Lopatin says. “It was his love letter to soft rock without any irony or guilt.”

Reitzell admits now that when he began working with Coppola, he barely knew what a music supervisor did. One of his first professional hurdles was figuring out how to get Jeff Lynne from ELO to license a song for the soundtrack. Lynne’s fee to place a song on the Boogie Nights soundtrack was six figures, a sum Reitzell didn’t have for the small indie film. “But I got Jeff Lynne into the screening room,” he says, “and he walked up to me after and said, ‘You can have my song for 50 cents.'” It was an early instance where Reitzell displayed a talent just as important as his compositional chops: the ability to get that impossible sound (or that stubborn artist) into his film work.

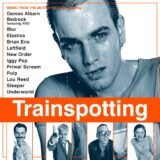

Having collaborated closely with French duo Air on Virgin Suicides, Reitzell signed on as their touring drummer. While playing a festival in Japan, he befriended another touring musician, Kevin Shields, who had been relegated to a journeyman’s role on guitar in Primal Scream, now that My Bloody Valentine was on a more-or-less permanent hiatus. Rumors of a follow-up had circulated for years, but a decade had passed with no new music whatsoever from Shields.

“Loveless was a really big record for me,” recalls Reitzell. “It was what was keeping me alive when I was still touring with Redd Kross.” He and Shields became fast friends. One drunken night, while walking through Osaka’s empty streets at 4:30 in the morning, Reitzell popped the question: “I asked him if he would ever be interested in doing a film score.”

And as Coppola began work on Lost in Translation with Reitzell, he knew that the woozy, dreamlike sound of MBV was perfect for a film about being adrift and sleepless in Tokyo. “Listening to [My Bloody Valentine] is like taking a drug,” he says. “For me, MBV sounded like it felt like being in Japan, being jetlagged, stimulated by all those sounds. So when I asked him to do it, he said yeah.”

Everyone in the industry thought he was crazy for pursuing a venture with Shields. “Close friends with Kevin said, ‘He’s never going to do anything; he’s never going to deliver,'” Reitzell says, but he believed he could help his friend in some small way. “To be honest, I didn’t need anything from Kevin, but I was on this mission to get something out of him. He still had it and he was trapped in Primal Scream, and I felt I could help him get out of that. And I did! With Lost in Translation, I may have helped him with some of that fear of finishing something.”

Shields ended up finishing four somethings for the soundtrack, but it wasn’t easy. “City Girl,” his longest contribution, is less than four minutes long, but it took months to complete, across three separate recording sessions at a studio in the crack-addled heart of Camden. Each time Reitzell returned there to work, he encountered a new studio engineer. Shields would only work at night, and he smoked pot constantly, insisting that Reitzell partake to make sure, as Reitzell puts it, “that I was on Kevin’s level.” Hours of useless, meandering sessions were recorded. “I never forced Kevin into anything,” Reitzell says. Finally, after weeks of false starts — once, it took eight hours just to get the guitar equalized just so — it all came together in an instant.

“One night,” Reitzell recalls, “I remember Kevin going, ‘Okay Brian, I’m ready.’ I was post-stoned, asleep; I was exhausted, and he says he’s ready. He has this crazy beautiful guitar sound, loud as all fuck. The guitar was in the isolation booth, not the drums. The guitar was so loud. Kevin’s whole trip is volume, that relationship of extreme volume with microphones. There were no effects pedals. He uses fewer effects than anyone I ever worked with. It’s pure science, it’s that physical air moving: That’s how he gets those sounds. He started playing these chords and a few minutes later, that song was done. It took weeks to get to that point and we played it once.”

Did Reitzell’s encouragement help bring about the return of My Bloody Valentine for last year’s M B V? Who knows, but in any case, Shields turned up again to lend a hand on Reitzell’s Auto Music. This time, he played organ on “Last Summer,” a song built on a process that Reitzell had discussed with him on those endless nights in the studio. Auto Music‘s nine instrumental tracks amalgamate three of Reitzell’s loves: music, film and cars. As we get ready to leave his studio to drive downtown for lunch, he pulls out a stack of DVDs that he used as inspiration for the album, having them projected in the studio as he and his cohorts played live; they include Andrei Tarkovsky’s Solaris, Víctor Erice’s The Spirit of the Beehive, Fellini’s Juliet of the Spirits, Oskar Fischinger’s early animations Ten Films, Teshigahara’s documentary Antonio Gaudí, and the collected films of Japanese director Yasujiro Ozu. Many of the song titles reference such films: the post-rock single chord churn of “Ozu,” the Talk Talk-like simmer of “Gaudi,” the quiet lullaby of “Beehive.”

He’s not the same sort of car buff as his father was, but the album does meld California’s car culture with Reitzell’s love of German krautrock, specifically the motorik beat of Neu! drummer Klaus Dinger. “‘Last Summer’ sounds like the wind is blowing in your hair, driving fast in California,” he says, beckoning me towards his black Mercedes Benz as we set off for lunch. He cues up the recently released Miles at the Fillmore as we drive.

At Water Grill in downtown L.A., Reitzell orders a platter of scallops and oysters on the half shell. By the early 2000s, he says, “We were having these dinner parties that were Sofia, myself, Spike Jonze, Mike Mills, Michel Gondry, all of these people moving from music videos to film. And I was the lone music guy with all these film buffs.” Originally the indie-rock outsider at the fringes of Hollywood, as this circle of film friends made inroads in the Hollywood establishment, Reitzell found himself enjoying more prominent soundtrack gigs.

Mills ended up tapping Reitzell to work on his first feature-length film, Thumbsucker. To soundtrack the film’s downer tone, they wanted to feature Elliott Smith. It had only been a few years since the release of what would turn out to be Smith’s final studio album, Figure 8, but the singer-songwriter was crippled with fear and doubt. “Elliot was paralyzed, he couldn’t go into his own recording studio, he was scared to death of it,” recalls Reitzell. But if anyone could coax Smith back into a studio, it was Reitzell. “Through my working with Kevin, he was able to make music again, which he hadn’t been able to do in 13 years. The people around Elliott knew that. I was the nurturer, I was the guy that could get Mike what he needed [for the film] and protect Elliot from Hollywood.”

Every day, Reitzell would drive to Echo Park, pick up Smith, and drive to West Hollywood, where the film was being edited. “He would get in the car with this Case Logic binder of 300 CDs,” he said. “It was all of his music. He had had his music stolen from him, so whenever he left the house, he took it all with him.” They had recorded a few songs for the film when Smith took his own life; ultimately, the soundtrack duties fell to the Polyphonic Spree. The resultant soundtrack wound up very different from what Reitzell originally intended, and he wonders at what might have been had Smith lived. Reitzell says that he even tried to put Smith in contact with Shields, but that Shields never got around to calling the troubled singer. “I think Kevin will regret that the rest of his life. He wanted to — he just never…” He trails off. “It’s Kevin.”

After lunch, Reitzell drives back to his house in Silverlake to bring his dog back to the studio. It is a modest house, but it would not be out of place on a tour of Los Angeles’ minor musical landmarks: The Dust Brothers recorded Odelay here in the early ’90s, and the Rolling Stones were here for the making of the Dust Brothers-assisted Bridges to Babylon. “Mick and Keef swam in my pool!” exclaims Reitzell.

When Reitzell began to put the music together for Sofia Coppola’s next film, Marie Antoinette, he again found himself courting two musical recluses. “One morning in London, when it was snowing out, I went to meet Mark Hollis over coffee and Aphex Twin for lunch on the same day.” Prolific through much of the ’90s, Richard James hadn’t put out any new music since 2001’s Drukqs, while Hollis, the former frontman for Talk Talk, hadn’t released a note of music since his solo album from 1998. Two Aphex tracks ended up on the Marie Antoinette soundtrack, and although Hollis’s music wasn’t the right fit for the film, Reitzell reached out to him again when he began working on Peacock.

“The producers wanted Philip Glass, but Mark loved the script, and then he made some music and sent it to me,” Reitzell says. “Hollis did it with the refined elegance of a great composer, but then I didn’t use it.” The reasons, he says, were all too typical for Hollywood: The studio meddled with the film, firing both the director and producer and drastically changing the film. “They took the movie away from everybody, so I protected Mark and pulled the music,” says Reitzell. (Ultimately, a sliver of this music appeared when Reitzell did music supervision for Gus Van Sant’s short-lived television series, Boss.)

I ask if he thinks this will be the last bit of music we ever hear from Hollis, now going on 15 years of silence. “My lips are sealed,” says Reitzell,” but I think there will be. There’s more to come from him.”

Perhaps it’s an extra testament to Reitzell’s abilities to coax recluses out of hiding that I couldn’t get any of them to comment for this story — or even to respond to my requests for interviews. Perhaps that’s not surprising, especially in the cases of publicity-shy figures like Shields and Hollis. But still, their continued reticence only drives home Reitzell’s almost uncanny abilities to draw out those who would otherwise prefer to remain hidden. How on earth does he do it?

For Reitzell, it comes down to it being a matter of respect: “You’re taking someone’s child, so we’re always super respectful. I showed Marie Antoinette to every artist. I even had Robert Smith come down to the set.” But if respect were all it took, then the cult-like reverence surrounding these acts would have already brought more of their work into the world in the 21st century. While being a geek about cool music is standard in most music circles, Reitzell’s sensibilities not only makes him an asset to filmmakers, but also an ally to musicians out of their element.

“Listen to the average score or soundtrack in 2014 and it’s totally formulaic: maudlin, cute, or some reductive take on Philip Glass. Brian is totally coming at it from a different place,” Dan Lopatin told me. “I think Brian’s just more a music head than he is ‘Hollywood.’ His approach is refreshing for musicians who approach their craft with any level of self-respect, and who are routinely weirded out by show business. Good taste like Brian’s is an anomaly in Hollywood.”

As we head back to his studio, Reitzell mentions that in another era he might have made millions composing film soundtracks, but his priorities are closer to those of the Replacements than U2. “I only want to make enough money to make more music,” he says. And with that, he goes back to work.