Founder and former music journalist Kiran Sande may have named his record label Blackest Ever Black as a lark, but his artists have taken to it like a mantra. There’s this Spinal Tap-like finality in the omnipotence that the name carries — what Sande will describe, laughing, as a “crashing overstatement.”

“You want a name that you could imagine, like, a biker having studded on the back of their jacket,” he says.

It’s an instant, almost comical declaration of unapologetic austerity for the music that would eventually come out on the label. And to the untrained eye, the most prominent artists to release music under that banner — the dubby techno deconstructionists in Raime, powerelectronics icon William Bennett’s Cut Hands, the gothy ambience of Tropic of Cancer — all hew to spectral hue of its name.

But Sande assures during an August Skype call, during which he naturally appears only as a silhouette, that these things happen with a wink and a nod back toward innocence and naivete. “It felt like a name that a teenager would call their record label, if they were sitting there with their doodle pads kind of trying to come up with a cool name,” he explains. “Obviously anyone at my age should know better than to do that, but I think that was, for me, a bit of a desire to channel that teenage way of seeing the world.”

If there’s an outlook that’s come to define the label in its now five years of existence, it’s in a willingness to acknowledge the world’s darkness, but suggest — however meekly — that it’s okay to grin anyway. Today, they’re sharing a new compilation called I Can’t Give You the Life You Want, featuring new tracks from a host of those acts, including a dread-filled ambient exercises from Dalhous and Secret Boyfriend’s brittle noise. It wasn’t initially intended as part of their fifth birthday festivities, but pressing plant delays forced its release closer to a pair of parties that Sande booked in London and Berlin featuring a number of the artists included on the comp and a host of similarly minded producer/composers.

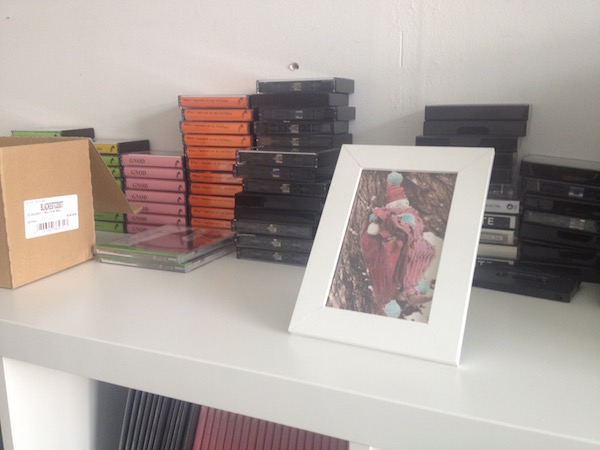

Stream I Can’t Give You the Life You Want here, as an demonstration of the depth and breadth of Sande’s label’s output, take a peek into their offices, and read an interview with Sande about the label’s origins and influence, edited and condensed from that Skype call and an ensuing email conversation.

As a former journalist for FACT, you’ve been involved in music for a while. What drove the desire to initially start the label?

It was actually a long time ago now. I always had a inchoate desire to start a label at some point in my life. So there was that in the background, but I think what galvanized things and made it happen is: It was a bleak time in London [Laughs.]. This has nothing to do with the perceived aesthetic of the label, but it just felt [like] me and everybody around me had no money, everyone was kind of miserable, a bit bored, and even the friends of mine who were deeply involved in music were all sort of depressed. I started over at that precise point because I had no money and no prospects, and in a way that’s the best time to start something like that, because I had nothing better to do. I know this is not a very inspiring story.

And meeting the guys in Raime figured in prominently right?

Someone passed me their demo. There was an instantaneous lightning-bolt moment where I went from having this gassy, indistinct idea and a desire to create a label without the faintest clue of what it would be, and then the whole thing just germinated. They were the friends I needed to meet at that time in my life because they completely re-enchanted me with music. Before the first couple of Raime 12-inches came out, I would talk with them a lot about music, about what we hated, and about what we loved. And basically we said — drunkenly, I’m sure — “fuck dub techno.” Dub techno was our whipping boy, a genre that was all about production and atmosphere but completely lacking in character and storytelling. And then as soon as the first Raime record came out, we read a review which said something like “exciting new dub-techno producers Raime.” [Laughs.]

It’s funny that you talk about it being a bleak time in London; how did you decided that you wanted to put something else bleak into it?

I would say a lot, if not the majority of the music on the label is certainly, you know, adheres loosely to a kind of bleak outlook or whatever you want to call it. But the point is the bleakness of the name is meant to refer the situation in which the label was created in practical terms: breakups, empty bank accounts, and a general sense that this was the worst possible time to start a label, and therefore the only time.

I’m not sure being po-faced was ever an aim as such, I think I just viewed it as an operational necessity. With a name like “Blackest Ever Black”, being anything other than po-faced — at least to begin with — would be farcical and self-defeating. Since then I’ve allowed a little bit of light into the label, the kind that would have probably been unthinkable to me in its early stages. But it took time to do that, I felt I had to earn it. Hopefully now we’re at a point where those occasional bursts of levity make the tragedies hit a tiny bit harder.

It’s always felt like there’s a sense of humor at the heart of the music you release; somehow behind the grimace, there’s a grin.

There’s an element of humor to it, sure, but it’s also deadly serious. The two are not mutually exclusive, and I reserve the right for it to be both. Personally I think a lack of humor fatally undermines seriousness anyway… I mean, how can you take someone without a sense of humor seriously? Just like people I like as friends in real life, every artist on the label is incredibly hard on everyone else and incredibly hard on themselves. And, you know, as a result there’s a sense of humor in it, blah blah blah. It makes it sound very cute and ridiculous. We all get on, the ones that I’ve met. And that’s a sign of something — maybe it is a mystical thing coming through. Maybe, one day I’ll start working with an artist who’s a total cunt and then the theory will go out the window.

So after releasing those first couple of Raime records, very serious, heavy stuff, was there a conscious effort to not get pigeonholed?

None of us had a clue what the f—k we were doing. I was certainly scared. I was so proud of those two records but I was very aware of what the third one was, it would would seal the label’s fate one way or the other. It sounds so silly now because underground music changes so much in five years, but without wanting to sound like a dick about it, at the time it felt like a kind of, it felt like a relatively bold and slightly suicidal move to follow [the Raime records], with the first Tropic of Cancer EP, something which was in essence this morbid sort of rock ‘n’ roll. We look back now on five years ago and it seems ridiculous that I thought that that was in any way daring, but it felt that way.

Then the sound of the label just ballooned out from there.

Exactly. Natural steps. Occasional lightning bolts and bright ideas, but mostly chaos and happenstance. I like this idea that each successive release has the potential to redefine what’s come before. I like to think that the moment you hear [experimental punk/black metal act] Raspberry Bulbs, you think differently about Raime, and Tropic of Cancer, and so on.

Five years on, how do you keep things surprising? Once you’ve covered so much ground how do you continue to be surprising?

It’s not my objective to “be surprising” — constant novelty would be a bit nauseating for everyone, I think. I follow the music, my own interests. Sometimes this takes us into new areas, sometimes it doubles back into familiar themes, familiar sounds. It’s not a very fashionable thing to say, but I think it’s perfectly possible to be progressive and classicist at the same time. And to tell you the truth, the internet has made classicists of us all, so that side of the equation is unavoidable — you might as well do it properly.

Blackest Ever Black Fifth Anniversary Shows:

September 26 – London, England @ ICA (with Jac Berrocal, David Fenech & Vincent Epplay, Officer!, Af Ursin, Raime, Ashtray Navigations, Stefan Jaworzyn, Dalhous, F ingers. and AD Jacques)

October 30 – Berlin, Germany @ Berghain (with Raime, Prurient, Tropic of Cancer, Regis, Felix K, Diät)