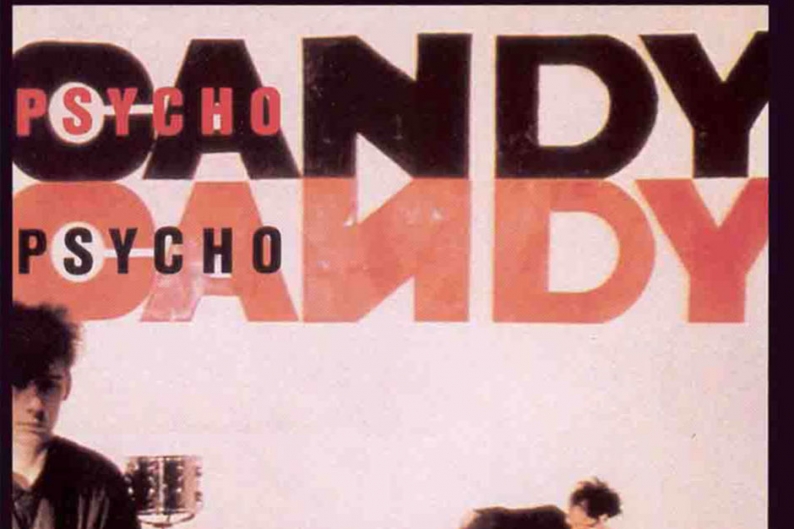

Nearly 30 years ago, the Jesus and Mary Chain — a band of pop-eviscerating Scots led by brothers Jim and William Reid — emerged with Psychocandy, one of the most rightfully acclaimed debut albums in history. A 15-track set heavy on sun-streaked hooks and ear-splitting distortion, the record has been canonized as an alt-rock classic, a Platonic ideal of noise-pop. In the years since its release, Psychocandy has become a fixture on best-of lists, been praised by Magnetic Fields mouthpiece Stephin Merritt as the “last significant event in popular-music production,” and endured as a touchstone for musicians everywhere — whether they realize it or not — who try and split the difference between the sweet and sadistic.

To celebrate Psychocandy‘s impending 30th birthday (the LP arrived in November of 1985), the Jesus and Mary Chain are parlaying their eight-year-deep reunion into an anniversary tour, wherein they’ll perform the album — along with era-appropriate B-sides and rarities — across North America. SPIN recently hopped on the phone with Jim Reid to discuss the upcoming trek, which kicks off in Toronto on May 1, as well as the legacy left behind by their first full-length.

How did this tour come together? Is it something that the band thought up or were you approached by someone?

People have been suggesting that we do a Psychocandy tour for quite a while now. It just never seemed right before. We thought, “Well, it’s the 30th anniversary, there would be no point in doing it in two years.” The other thing is we started to look at the reasons why we didn’t want to do it. I suppose when people said, “Do a Psychocandy tour,” we were kind of thinking, “Well what does that mean? Does that mean we have to act like we did during that time period? Do we have fall around the stage drunk and stuff?”And it just seemed like that was off-putting.

And then we thought about it — there’s quite a chunk of that record that was never played live for whatever reason. We thought, “Well, instead of making it about the controversy that surrounded the record or the band at the time, let’s just make it a celebration of the actual record, and go out and try and play that album live as faithfully as we can.”

What’s your relationship with Psychocandy now?

I am very happy that it happened and that we made it, but it is a complicated thing. You’re making an album. The further you get from the actual record, the kind of stranger it seems to you. It’s a photograph of what was going on inside a person’s head — of me and William in 1985 — Psychocandy is it. It’s like looking at an old photo album of your life back then and you smile a bit and think about how much you have changed. But it’s a nice feeling to go back and revisit that time.

Did you have any idea when you were making the record that it would have such an impact that you’d be celebrating its 30th anniversary?

I suppose at the time we hoped that this was going to be an important record that was going to have a life of its own. There’s no guarantee and you never know that. At the age — I was 23 when Psychocandy came out — you just can’t imagine 30 years’ time when you’re that age. It’s so abstract and you just can’t get your head around it.

When the Magnetic Fields put out their Distortion album a few years ago, the organizing principle of the record was to just drench everything in distortion. Stephin Merritt said that he was inspired by Psychocandy because he thought that was the last time something truly new had been done with music.

I remember that and it’s very kind of him to say that. I would have to disagree: Rock’n’roll, call it what you like, runs in cycles and it’s never been brand new. Each new generation is going to hear it for the first time, but all of us oldies will be saying, “Oh, I’ve heard all this before.” I’m sure that when Psychocandy came out there were a bunch of old guys going, “Oh, this is the Velvet Underground” and it was!

Rock’n’roll is a borrowed art form. The Rolling Stones borrowed Chuck Berry. Chuck Berry borrowed Muddy Waters — that’s how it works. You have to be careful to avoid pastiche. It’s easy to look at another band’s ideas and completely rip them off — but there is no point in doing that. You have to put a little bit of your own identity in there. I think the greatest records are like that: People try to emulate their heroes, but either got it wrong and it ends up being unique, or their personality is so strong that that comes through.

There’s a Lou Reed quote where he says something to the effect that he started the Velvet Underground because he wanted to take the writing of William S. Burroughs and set it to rock music. Did the Jesus and Mary Chain have any kind of mission statement like that?

I’ve never heard that quote before but I don’t believe that. It’s just one of those things that sounds good. And, yeah, it sounds plausible because the subject matter that he was dealing with wasn’t a million miles away from the likes of Burroughs and Ginsberg, but at the same time the Velvet Underground were a pop band. They were an extreme-pop band that sang about heroin and going to meet your man on Lexington and 125th, but it’s still pop music. I always thought that the Velvet Underground were just pop music that didn’t understand the boundaries.

I wouldn’t dare to compare the Mary Chain and the Velvets, but in that respect, I would say that describes what we were doing. We had no clue as to what you were allowed to do or what was acceptable, we just went out and did whatever the fuck we wanted to do. A mission statement? “Psychocandy” is it. That describes everything of what the band was intending to do in 1985. “Psychocandy” is not just the album title, it’s a description of the album and it’s a description of what we were trying to do at that period in time.

The first time I heard the record, something clicked halfway through — when I got to “Some Candy Talking” — and for some reason I found myself wishing I was a teenager in the ’60s, not the ’80s.

I felt that. I wasn’t a teenager in the ’80s — well, I was for a portion — but the ’80s was a decade that we found ourselves in. It wasn’t a decade that we particularly identified with. A lot of the things that were important to the Mary Chain at that time were things from 20, 30 years before.

What seemed important to people [in the ’80s] just appalled us. In Britain, it was all about Margaret Thatcher and grab every little penny that you can and fuck everybody else. That kind of filtered through everything, into art — certainly music and movies. If you look back at things that were made in ’80s, a lot of it had no soul. We were very aware of that as it was happening. I don’t think that many people were, but the ’80s were not a great decade.

You’ve played a few gigs for the 30th anniversary tour in the U.K. already and you’re getting ready for Canada and the States. Do you notice any differences between the U.K. crowds and the North American ones?

Generally speaking, an audience is pretty much the same the world over. You’re standing in front of a bunch of people that hopefully have bought your records and seem to know what you’re all about. Obviously, the longer you’ve been around, the friendlier the audience is.

Back in ’85, during the Psychocandy times, it wasn’t necessarily like that. There was a lot of hostility from the audience because, basically, the Mary Chain grabbed people by the throat. Live, it was quite aggressive. We were quite shy people so the only way we could think to do it was to get pretty fucked up on stage, which made it all a bit chaotic. It wasn’t “show business,” put it that way. A lot of people had heard the hype and had been coming along out of pure curiosity. You certainly weren’t standing in front of an audience that you already had in the bag. You had to win them over. We were not very good at doing that.

How have you changed as a performer over the years?

I’ve come to terms with what I can and can’t do. But back in those days, I felt as if I just didn’t have what it took, andthat was a lot of the reason I would get very, very drunk or take drugs on stage. It’s because I just never felt good enough. I used to want to be Iggy Pop but I couldn’t — I was just too crushed with shyness. It’s not easy for me. I don’t talk to the audience and I hope at this stage of the game, people know that I’m not being aloof and I’m not being rude. I just focus on the songs and by doing that, I think I enjoy it now more than I ever have.

Does it ever get frustrating to feel like Psychocandy cast a shadow of the rest of the catalog?

It did for while. You’d have a new album out and people wanted to talk about Psychocandy, so you’d be like, “Yeah, but what about the new record?” It could be a bit annoying depending what was going on at the time. All this time later, it’s great. If you’ve got one record that 30 years after it’s released people want to come and hear you play it live… that’s a great thing. Fabulous. I’m not going to complain about that.

Which Jesus and Mary Chain records are you most comfortable listening to on your own time?

It’s a weird thing. I do, from time to time, listen to an album, but it’s not very often. You don’t really listen to your own music. It’s kind of a thing that you get feverish about when you’re making it. But once it’s done, it’s done. You always want to change the music that you made.

It’s never perfect. You go into the studio — if you didn’t discipline yourself, if you didn’t force yourself to say you’re finished now, you would continually record and tweak that record for forever till doomsday. You get to the point and say, “Well, fuck it. We’re gonna have to see. It’s finished now.” So if you don’t listen to it for a year and then you go back to it, you hear all of the things that you would have changed. It’s a bit frustrating. But obviously, at the same time, it’s like revisiting an old, comfortable pair of shoes.