After a breakup left him “completely destroyed,” Marilyn Manson strikes back with a new (very young) muse, an intensely personal album, and a distaste for crotch panels.

Black metal gates swing open, and I steer my car up Marilyn Manson’s driveway. It’s a small hill, and there are odd, looming trees on both sides, forming a canopy, a scary dark tunnel. Manson lives in Chatsworth, a suburb of Los Angeles, it’s around 9 P.M. on a moonless March night, and I feel like I’m in a goth version of Sunset Boulevard. Will I end up dead in some swimming pool, like the writer played by William Holden?

I ring the front doorbell of the mansion, which has a grand, old-Hollywood look to it. The door opens and standing before me is a stocky young man in a dark T-shirt and loose jeans. There are two rings through his lips.

“Follow me,” he says.

I enter the front hall, and about 20 feet away is a large, empty circular room; the only thing in it is a single white cat. Its shoulders are hunched, and it looks frightened. My eyes are a bit weak, and I wonder if it’s a statue, some kind of joke, so that Manson’s guests are always greeted by a white cat instead of a black one.

“In here,” says the man, indicating a door to my left. I enter a dark chamber.

“Wait here for Manson,” he says, and leaves, closing the door behind him. His manners are grave, formal, and elegant, despite his casual dress and seeming youth.

I sit down, and my eyes adjust to the candlelit gloom. I’m in a smallish den with black-velvet sheets sealed tight over the windows. There’s a flat-screen TV, a couch, an Apple computer, and an old-fashioned Torpedo typewriter. The walls are lined with bookshelves holding hundreds of DVDs, and standing to my right is an eerie three-foot-high wax statue of Alice in Wonderland. On the table next to me is a yellowed human skull, the nostrils acting as a holder for some black pens.

RELATED VIDEO: Marilyn Manson on Lewis Carroll

The teeth are rather rotten on the skull, and I think how I haven’t been to the dentist in ten years. Then I wonder nervously if I’m being watched on a hidden camera.

Manson’s manservant comes back into the room and hands me a clear goblet with a pinkish liquid. There’s no smoke coming off the top, but I feel like there is.

“Absinthe,” he says, and stands over me, silent and erect. He’s an excellent manservant, and I appreciate his discipline and freakish behavior.

I’m not supposed to drink, due to mental problems and mild liver problems, but I immediately take a sip, like a willing Jonestown suicider. The absinthe is chilled, refreshing, and tastes of licorice. The manservant watches me.

“What’s your name?” I ask, bravely.

“Arvin,” he says.

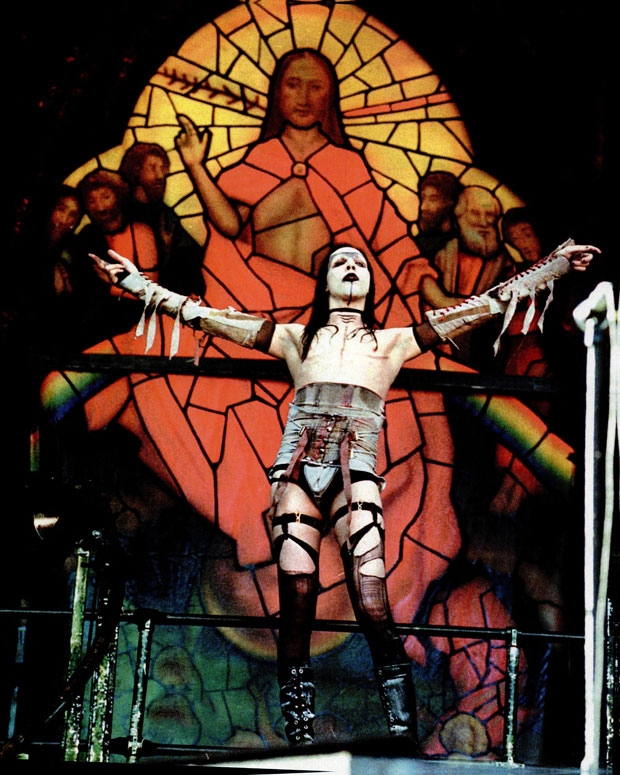

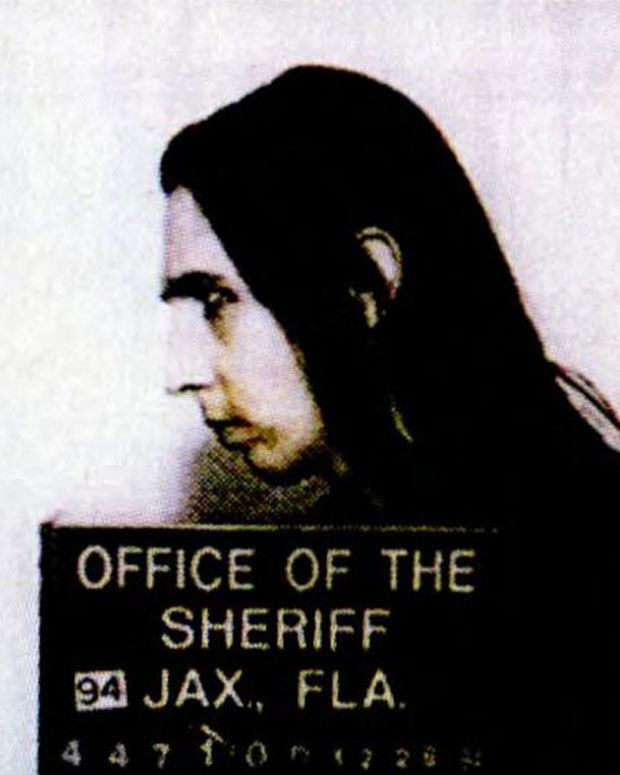

We lapse into silence. Sipping my absinthe, I try to gather my thoughts. I’ve spent the last few days reading Manson’s excellent autobiography, Googling him, and listening to his music. I review what I know: Manson, born in 1969, was raised in Ohio, where he attended a Christian school, which was meant to frighten him into obedience but had the opposite effect, sort of like the therapy in A Clockwork Orange gone haywire. His real name is Brian Warner and his grandfather was a cross-dresser who enjoyed dildos. His father poured Agent Orange on the jungles of Vietnam and dressed up as Gene Simmons when he took little Brian to a KISS concert in 1979. Manson has put together his own philosophy of hedonism, nihilism, and self-fulfillment, merging such disparate thinkers as Nietzsche and Anton LaVey, the founder of the Church of Satan. He began his postcollege life as a journalist in Florida, but then started playing music and broke out nationally, with Trent Reznor as his mentor, in 1994. Then, in 1999, he was partially blamed for the Columbine High School shootings, but resuscitated his career with an appearance in Michael Moore’s film Bowling for Columbine. Moore asked him what he would say to the kids of Columbine, and Manson answered brilliantly, “I wouldn’t say a single word to them. I would listen to what they have to say, and that’s what no one did.” Now he’s releasing a new album, Eat Me, Drink Me – his first in four years – and will embark on a co-headlining tour with Slayer in July.

The door swings open and Manson lopes in, carrying his own goblet of absinthe. He’s wearing a black T-shirt, black leather pants, and gigantic Frankenstein boots. He’s six-foot-three and looks to be all narrow torso and legs. I’m middle-aged and completely bald and immediately assess that Manson’s black hair is beginning to thin, probably from multiple dyeings. His face is sweet, and his eyes, without his usual colored contacts, are kindly.

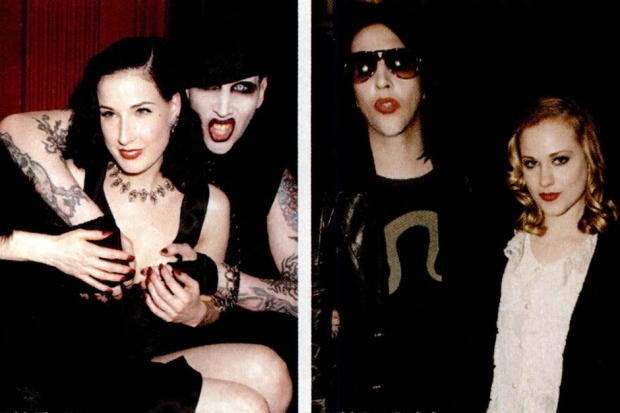

We start to talk, and Manson is sniffling a little. Right away, he starts to tell me about the breakup of his marriage to burlesque queen Dita Von Teese. They were together for six years and then, in their seventh year, they got married. “It’s the old cliché,” he says. “Marriage changes everything.”

The behavior he had manifested for the first six years – such as living like a vampire – became unacceptable to Von Teese, he says. But he wasn’t willing to give up his vampire’s hours. “I’m my most creative between 3 and 5 A.M.,” he says. “That’s the way I’ve always been.”

RELATED VIDEO: Marilyn Manson on His Marriage to Dita Von Teese

Going to sleep at dawn and rising at dusk was not the only issue of contention, though. Before they were wed, Manson and Von Teese were never separated for more than five days; after they got married, he wasn’t seeing her three out of every four weeks, due to her own hectic schedule. Manson is very needy, and with Von Teese on the road all the time, he started losing his mind. And he started believing her when she said that the way he lived was wrong.

“But then I realized that what’s wrong about me is right,” he says. “To play devil’s advocate – but that doesn’t really work, since I’m the devil – people would say that drugs and alcohol wrecked my marriage. But buyer beware. She said she had tolerated the lifestyle because she hoped I would change and threatened to leave if I didn’t. I was sleeping on the couch in my own home. I was no longer supposed to be a rock star. I was someone who had to be apologized for. I wasn’t prepared to be alone. I came out of this naked, a featherless bird. I needed to get my wings back by making this record.”

While his marriage was disintegrating, Manson met-then-19-year-old actress Evan Rachel Wood at a party, and a platonic friendship developed. He began to talk to her about appearing in a film he’d written, Phantasmagoria-The Visions of Lewis Carroll, concerning the author of Alice In Wonderland.

At one of their early meetings about the project, Wood wore heart-shaped glasses and looked like the movie poster for Stanley Kubrick’s Lolita. Seeing her in the glasses, Manson had what the French would call a coup de foudre – his heart was pierced. It turned out that Wood, like Manson, is a huge Nabokov fan and had worn the glasses on purpose, to acknowledge and ironically wink at the subtext of everything going on – Carroll’s long-rumored young-girl fetish, not to mention the 19-year age difference between Manson and herself. (Manson, a great believer in connections and coincidences, points out that Nabokov translated Alice In Wonderland into Russian.)

While Manson was separated from Von Teese, his friendship with Wood eventually turned erotic. One day the actress was licking a heart-shaped lollipop, and then she kissed him. He told her she tasted like Valentine’s day and immediately wrote a song about it, “Putting Holes in Happiness.” “She’s nothing less than a muse,” he says.

Wood now lives with Manson, and they collaborated recently on a video for the single “Heart-Shaped Glasses.” It’s one of the first videos to use James Cameron’s 3-D technology, and Manson was the star and director. It took four days to shoot. Cameron came to the set when Manson and Wood were filming a love scene and put himself in the director’s chair. Manson and tells me that Cameron said to him, “I’ll worry about the sweet spot and you worry about the G-spot.”

A few months before, when Manson was wildly depressed over losing Von Teese, Wood said that she would die for him, that they could die together. “It might sound strange,” Manson says, “but this made me want to live.” To me, it doesn’t sound strange. I once attended a goth music festival in Illinois, and one of my chief impressions was that goths are a very romantic people. To them, the dark costumes and the blood are imbued with romance and beauty – their apocalypse is someone else’s rainbow, is what I’m trying to say.

So Manson, like the goths who follow him, is a romantic, and it’s his most endearing quality.

After about two hours of drinking and talking, Manson wants to play Eat Me, Drink Me. “This album was borne out of depression,” he says. “But it’s also about cannibalism in a romantic sense, the idea of wanting someone so bad you want to devour them.”

Before the album started coming together, though, he couldn’t make any art for months; his misery over his failing marriage was consuming him. “I was completely destroyed,” he says. “I had no soul left. I define myself as a person, a human, an artist, as someone who makes things – writing, painting, music – and I couldn’t do anything.”

One day he was telling his guitarist and coproducer, Tim Skold, about his heartbreak, and Skold said, simply, “Why don’t you write a song about it?” Manson was shocked by the suggestion but followed the advice. “It’s strange, but it never occurred to me to work that way,” he says. “I’ve never laid myself out there like I have in these songs.”

He puts the CD into the stereo and it’s beautiful and devastating. Reading the lyrics as I listen, I think of the album as the love child of Von Teese and Wood, equal parts despair and joy. It mourns the loss of Von Teese and celebrates Wood’s embrace. I occasionally look up from the lyrics, sneaking peeks at him. His eyes are closed and the long, thin fingers of his left hand touch his pale temple. At one point, I nearly start crying – the music and the absinthe are working on me, and I’m thinking of all my breakups, all that lost love. Then the album is over and Manson says, “You look like you were moved.” I realize he’s been sneaking peeks at me as well.

Arvin, as he has throughout the night, comes in and refills our glasses while Manson is telling me how all his previous records had been fueled by nihilism and range at the world, but then, he says, “I become so deeply depressed, which is different from being nihilistic. You have nothing to live for. For the first time, I lost hope.”

For the first time? I think. I’m shocked by this. I haven’t had any hope in years. Manson goes on to tell me that he’s more or less back to his old, strong nihilistic self. But all of this disturbs me. Am I darker than Marilyn Manson?

I express to him that being a nihilist is a form of idealism – you don’t want to tear things down if you don’t think things could be better somehow – and he agrees. But I’ve never thought that way. I’m a despairist. I don’t get angry at the world; I go straight to sadness. I sometimes secretly hope that man can change, but mostly, I’ve given up.

I’m rather inebriated and don’t want to think that Manson is delusional. So I say to him, feeling slightly hysterical, “Do you really think, as a nihilist, you can change things? Change the world?”

He sips his absinthe and says, calmly, “No. I can’t change anything.”

He goes on to talk about Wood’s role in Across the Universe, Julie Taymor’s upcoming impressionistic film featuring Beatles songs, and he mentions the title song’s famous refrain: “Nothing’s gonna change my world.” I tell him that I know that song well – an old girlfriend put it on a breakup mixtape, and I’ve wept to it many times.

Manson then tells me he referenced the lyrics in his song “Lamb of God” (from his Holy Wood album), about the death of John Lennon, changing it to: “Nothing’s going to change the world.”

I find all of this is very soothing and reassuring. Manson is not delusional, and I feel less alone. We’re of the same mind: There’s nothing to be done.

Around 2:30 A.M., we head for the kitchen to get more absinthe. It’s my first time in the main part of the house. We walk down the hallway and the white cat, like Alice’s white rabbit, is gone.

In the kitchen, Arvin is putting out some food for Manson – a steak and salad. Looking at the food, Manson says, “I have a weight complex. I want to stay skinny, so I try to eat well. I try to come right up to the edge between healthy and not healthy.” He sips his absinthe. “You have to get your body to the point where germs are afraid to live.”

He pours me some blue absinthe – absinthe, apparently, comes in different colors – and he tells me that a German distillery is developing a brand just for him: Mansinthe.

Absinthe, due to its high alcohol content, is not sold in the U.S. Also, it contains wormwood, which is thought to cause mild hallucinations – and I have noticed, as the night has worn on, that all sources of light seem to sparkle. Manson tells me he drinks the stuff because it doesn’t fatigue him, and because the long history of artists – such as Poe, Rimbaud, and Van Gogh – favoring absinthe appeals to him.

We leave the kitchen and walk about the house, which was once owned, he informs me, by the actress Barbara Stanwyck. The place is pretty much devoid of furniture. I do spot one chair. Sitting in it is a human skeleton with an animal head.

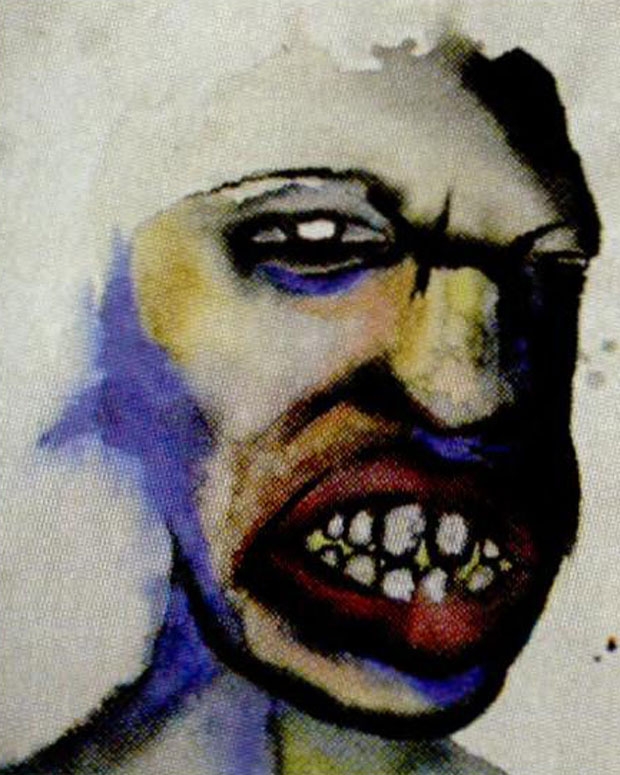

We go into Manson’s music studio, which is littered with equipment and looks like the lair of a mad scientist. We also visit his painting studio. In the middle of the room is a 19th-century embalming table that is permanently marked by the brownish strains of dead bodies.

“I thought I might make love on it,” Manson says.

Instead, he recently decided to paint a portrait of Jesus on the table. Manson wanted the death stains to come through the face of Jesus, as a sort of homage to the Shroud of Turin.

As I admire his work, he tells me about the art gallery he opened in Hollywood, the Celebritarian Corporation. The address is 667 Melrose Avenue. “That wasn’t intentional,” he says. “My neighbor is a church. They might be 666.”

We step outside, and there is a pool in which William Holden could have floated very nicely. Staring through the trees, I can see the lights of the nearby homes. “If I was a kid in this neighborhood, I would definitely bug Marilyn Manson,” he says. “That’s why I get up on the roof with my pellet gun sometimes, paranoid that there are intruders.”

We go back inside and Manson says, “Arvin will drive you home. You’re very drunk. We don’t want you to be killed.”

“Thank you,” I say.

A Phone Conversation, March 26, 2007

Jonathan: Hi, Marilyn.

Manson: Hey, you got me really drunk last night. That never happens. I was trying to keep up with you.

Jonathan: I’m sorry. I realize I just called you Marilyn. Is that all right?

Manson: Anyone who’s close to me calls me Manson. Strangely, I’ve never felt comfortable introducing myself with a woman’s name. For me, the name works only in its entirety. For brevity’s sake, it became easier to call me Manson. Early on, they called me M, but then Eminem sort of stigmatized that. He actually said – and we know each other and get along famously – when he was first starting out that he wanted to be the rap Marilyn Manson. He asked me to sing on his first record, and I would have, except that the song he asked me to sing was – and this might sound strange – too misogynistic. It was the one about killing his girlfriend and putting her in a trunk. It was on a record I could listen to, but it was too over-the-top for me to associate with. It didn’t represent where I was at. First of all, I don’t drive. And I wouldn’t put a girl in a trunk; that’s where I keep other stuff. That’s my dry, deadpan humor kicking in.

Jonathan: What about Trent Reznor? What’s the status of your relationship?

Manson: I don’t really have an answer for that. A while ago, I saw he said something derogatory about me in the press, and I called him up and said, “Why should we fight?” I have no hard feelings. He has my former bass player playing for him; that’s the only thing we have in common. He may be very muscular right now, but I’m a much more dangerous person.

Jonathan: What are your sexual fetishes?

Manson: First and foremost: women’s stockings. Stockings are such a fetish for me. I still wear them onstage. I particularly like translucent ones or skin-tone. I associate them with my eighth-grade Bible teacher. But she was probably wearing pantyhose with a crotch panel. I also like women’s feet. If I see a woman with ugly feet, I get angry. And I like looking at women’s shoes in a store, imagining them on a girl.

Jonathan: I once read this great thing about a shoe fetishist in Krafft-Ebing’s Psychopathia Sexualis. The guy was more in love with is wife’s shoes than with his wife, and he couldn’t perform in bed with her. So Krafft-Ebing or some other doctor told him to nail a shoe over their conjugal bed and to look at the shoe while he made love to his wife, and maybe then he would be able to perform. I always like thinking of that shoe nailed over the bed.

Manson: Yeah, if I was a psychiatrist, that’s the kind of thing I would prescribe. That’s the kind of doctor I would be!

Jonathan: Are you close to your parents? I couldn’t believe it when I read in your memoir that your dad would say to your friends, “Have you ever sucked a dick sweeter than mine?”

Manson: Yeah that’s my dad. He’s still potentially perverted. My parents are retired. My mom is going through a rough period. I support them. I’m closer to them now.

Jonathan: You’re a good son.

The following evening, I’m performing at a club in Hollywood called Largo. I’m a writer, but sometimes I do comedy. My friend Fiona Apple has come to see me and provide support, and thinking of all the weird connections, I recall that Fiona once covered “Across the Universe.” Manson shows up with Evan Rachel Wood and sits with us. Fiona and Manson have met before, years ago, and are happy to see one another.

Manson is wearing a fedora and offers me a hit from his flask of absinthe. Having to perform, I decline. Wood is much more beautiful in person than in the photos I’ve seen. She looks like a young Grace Kelly.

Aimee Mann starts the show with a few songs, and then the comedian Patton Oswalt takes the stage, followed by me. I tell a number of stories and do an extended monologue on how in high school, after reading a letter in Penthouse magazine describing such an action, I put a hairbrush up my ass, producing a violent orgasm. When I get offstage, Manson hugs me and says, “I’m your number one fan! I also had a hairbrush put up my ass once!”

Afterward, Manson tells Mann how much he admires her music and her role in The Big Lebowski, a film he worships. Then a bunch of us go to Bar Marmont, where Manson has secured a VIP table.

Fiona doesn’t like the scene and takes to drawing elaborate faces in a journal. The bar, I observe, is filled with Paris Hilton knockoffs, like fake Rolexes. It occurs to me that Hilton is a knockoff of some sort. I think of Manson’s song “The Beautiful People.”

Manson’s friend Stanton LaVey, the grandson of Anton LaVey, joins our party and tells me, “Manson is the most revered Satanist, second only to my grandfather.” Dave Navarro comes over to shake Manson’s hand.

I ask Wood what her fetishes are. She looks adoringly at Manson and says, “Boys in eye makeup are the greatest thing ever – that whole androgynous thing.” The two of them are madly in love. They are beauty and the beast, like Manson’s name personified. Wood used to be in a TV show called American Gothic, and now she’s really living it. About her attraction to androgyny, she explains: “I’ve been obsessed with David Bowie since I was five – that’s what started it.”

“We have so many mutual obsessions,” says Manson, also an enormous Bowie fan. Then he tells her, “Show him your tattoo.”

Wood pulls back her skirt, and on her upper thigh, right next to her adorable red panties, is a black heart with a lightning bolt inside. “The black heart is for me,” says Manson, “and the lightning bolt is for Bowie.” He shows me a black heart he had tattooed on his inner wrist as an expression of his love for her.

I then have this poetic thought that if Bowie was the man who fell to earth, then Manson is his dark mirror – the man who came out of the earth, the suburban earth of Middle America, vomited out of his Christian-school upbringing, the child of a Vietnam vet. Manson and his father used to go to a support group for families affected by Agent Orange. You don’t get more grotesquely American than that. You don’t get any more American than Marilyn Manson.

My thoughts are interrupted when a short, squat man approaches Manson and says, “Hi, Brian.” He shakes Manson’s hand and walks away. I realize that it’s Lars Ulrich, the drummer for Metallica. It’s like Manson is the Godfather – people keep coming over to pay their respects, including other rock stars. He says to me, “Whenever someone wants to act like they really know me, they call me Brian. But not even the people I sodomize – and I’m not saying I sodomize Evan – call me Brian.”

Then he beckons me to come with him to the bathroom. Arvin materializes, follows us, and stands guard.

“Want to do drugs?” Manson asks.

“What kind of drugs?” I whine, scared.

“You know what kind of drugs I do,” he says, and I think of his runny nose two nights before.

“I have a flight in the morning,” I whimper.

“Come on,” he says. “It’s rock’n’roll.”

I look at Arvin and then follow Manson into the toilet.

A few hours later, the sun is up and I pull into a gas station on my way to the airport. As I pay for the gas at the register, I see that amid the display of magazines is a copy of Penthouse with Dita Von Teese on the cover. The coverline reads: SEE WHAT MANSON’S MISSING. This is too strange. I buy Penthouse for the first time in probably 25 years, but I feel a little embarrassed and try to explain my purchase to the cashier, “I know him. Marilyn Manson.”

“Really?” the cashier responds.

I get in my car and open the magazine. Von Teese is certainly very beautiful. Then I go to the letters section, wondering if there will be any more coincidences, but I don’t see, much to my disappointment, a single letter about hairbrushes going up anyone’s ass.