It’s a crisp spring morning, and Wyatt Cenac’s staff are down to the wire prepping for the premiere of his new show, Wyatt Cenac’s Problem Areas, which will debut on HBO the following week. Charts and clipboards litter the white walls that carve their large office floor into cubicles—everyone seems to be either just finishing a very important conversation, or just about to start one. But Cenac retains his aura of prankster cool, shadowed distantly by an assistant and welcomed warmly across the floor as we head into his sun-drenched corner office. The forty-one year old comedian, actor, and producer has the affect (and build) of a mid-twenties slacker with an optimist streak. With strangers he talks slowly and ambles along, searching through sentences for the best way to express a point or the ideal moment to slip in a punchline. “You know how in college when dudes are pledging a frat, and they disappear for a few months and grow their hair out?” he says. “I feel like I finally crossed.”

Cenac is most well known for his scorching presence in the golden age of Comedy Central’s The Daily Show with Jon Stewart. He was a regular correspondent on the satirical news program from 2008 through 2011, and his segments routinely stole the show; Cenac seemed to dance closest to the edge, playing against Stewart’s permanently-stunned straight man act in sketches that combined cunning social and racial humor with bug-eyed, Tom Greene-esque absurdism. Fans who have followed him since his departure from the show have had to follow closely. Cenac acted in animated series like Archer, The Venture Bros. and Bob’s Burgers; starred in TBS’ People of Earth and his own web-series; hosted Night Train, a weekly stand-up show in Gowanus; and recorded three comedy albums, including the 2015 Grammy-nominated Brooklyn.

Wyatt Cenac’s Problem Areas is his first time at the helm of show with full creative control; he developed the concept, hired the staff, pitched it to HBO, stars in the series, and serves as its executive producer. (John Oliver and longtime Daily Show writer Hallie Haglund are among a handful of other executive producers involved.) The show combines scripted segments, field interviews, and animation, for an in-depth report on a broad topic, or “problem area,” over a full season; the first issue they’ll tackle is policing in America. Throughout the season, Cenac visits various major cities to hone in on specific aspects of policing and how practices compare across the country, while exploring tangential issues like homelessness and covering topical human-interest stories.

The series’ non-traditional format evolved over time, Cenac says. While concepting an early version, he looked back at old government-funded public affairs shows from the late ‘60s that focussed on African-American issues, such as Gil Noble’s award-winning Like It Is, which featured in depth interviews with politicians and activists for over forty years on WABC. “So many of those shows were born out of the Kerner Commission,” Cenac explains. “In the aftermath of the Civil Rights Movement, this recognition, federally, of, ‘OK, we need to provide spaces for underrepresented communities, people of color, to tell their stories to their cities, to their nation.’”

Cenac’s twist wouldn’t be his if it was too serious; laughter, he says, has long been a medium for education. After all, it was during his tenure at the Daily Show that a generation of undergrads were trained to get their news from comedy. “You always had a little bit of that,” Cenac says, citing the Smothers Brothers and Saturday Night Live as examples. “There was still an element of people getting information from satire, whether it was comedians like Pat Paulson, or Dick Gregory, or Richard Pryor, or even Chris Rock... I probably learned more about Marion Barry listening to Chris Rock than I did reading a headline.”

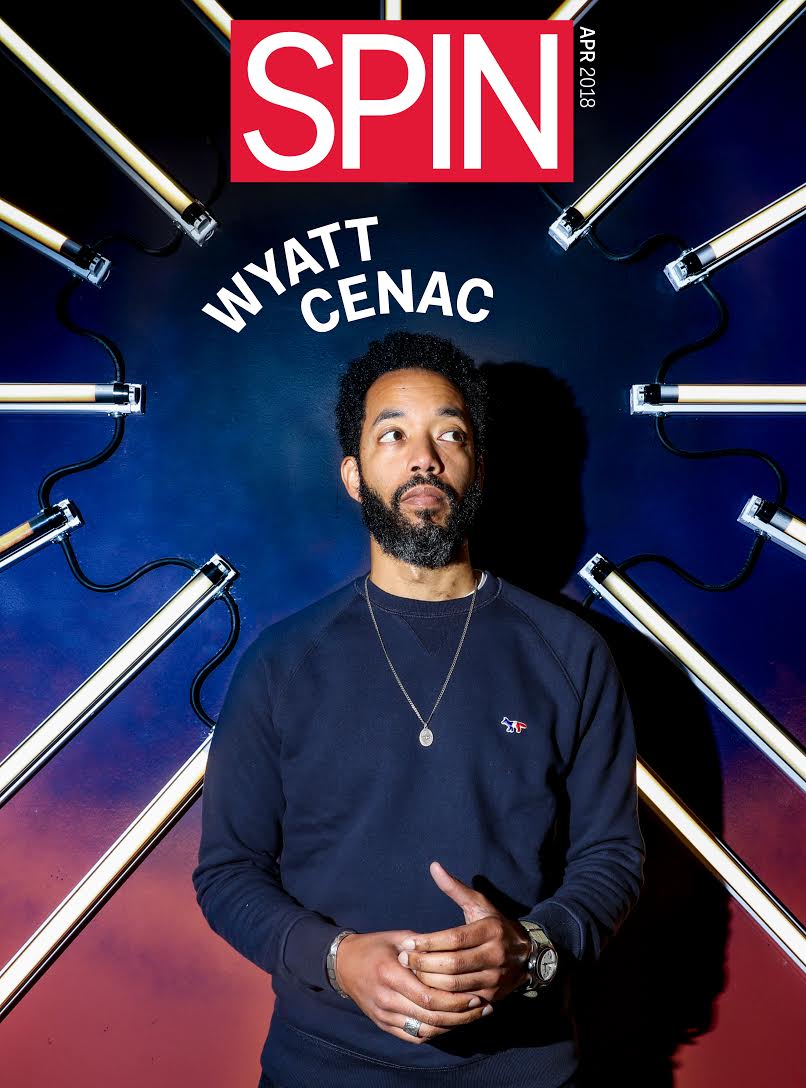

[caption id="attachment_id_286605"]  Krista Schlueter for Spin[/caption]

Krista Schlueter for Spin[/caption]

The first time Wyatt Cenac made someone laugh, he knew he’d earned it. As a kid in Cleveland, Ohio, he’d befriended a classmate named Brian who kept him in stitches. “I would try to make Brian laugh, nothing. I would try to make my mother laugh, nothing. Nobody ever fucking laughed at me. And I’m sure there are people like, ‘they still don’t, nigga.’” With a crowd like that, it’s easy to see why he would remember actually landing a joke. “Brian had this friend, this little girl who was our age. I don’t even remember what I said, but I said something and she laughed, and I remember that feeling. Then I said something else and she laughed again. I was able to keep it going, just naturally. I felt this wave of, ‘Oh, this feels good.’ I’m making this person laugh. I didn’t really know any other feeling like that.”

Raised between suburbs of Dallas, Cenac spent summers with his grandmother in Crown Heights at the height of the crack epidemic of the '80s. When he was a child, his father, a taxi driver, was shot and killed in his car by a teenage passenger; he discusses the experience in depth in the semi-biographical Brooklyn, where he connects the trauma to his lifelong love of Batman, a grieving child turned vigilante community hero. He caught the comedy bug early, rabidly consuming his grandmother’s gifts of Bill Cosby comedy books (which is something he shows some uneasiness about now), and boasts to this day about being able to distinguish between the styles of Looney Tunes animators Tex Avery and Chuck Jones; as a teenager he watched In Living Color and Eddie Murphy and Bill Murray on SNL. “It wasn’t until college that I thought [working in comedy] could be possible,” he says.

Cenac tells me about a particular high-school experience that led the way, when his parents made him take a test for gifted black students that would help place them in notable internship programs that match up with their skill sets. “Some people talk to you and they’re like, ‘You all are the Talented Tenth,’--they tell you all that shit. You take this test, and based on this test, it’ll place you into whatever. If you should be in finance, they’ll pair you with companies.” He remembers taking the test alongside “two hundred or three hundred kids” and getting his results. “Mine comes through, and the first thing it listed as a possible career path for me was stuntman. No bullshit. Stuntman.”

“They were like, we got nothing for you. There was a list of ten things on there--it might have been stuntman and circus performer. I told my step-father, like, ‘yeah… the test said I should be a stuntman…’ But he was like, ‘you’re still gonna be a doctor right?'”

By 1996, Cenac was gigging around campus open mics at the University of North Carolina, where he was a student, and mailing sketches to Saturday Night Live, addressed to the names he saw in the credits. “They’d send the sketches back and we did this dance for months because, legally, they can’t read them,” he says. “There was someone at Lorne Michaels’s desk who was getting these sketches and would have to send them back to me.” Eventually they replied, pointing him toward the internship department. Vets like Colin Quinn and Tracy Morgan took a liking to him, which Cenac says made him feel he truly belonged in comedy. “I remember Tim Meadows gave me a radio. It was a radio he didn’t want anymore,” he tells me. “I gave it to my grandmother, and she had it ‘til the day she died. To me it was, ‘I got a thing from Tim Meadows!’ I think my grandmother was like, ‘I got a thing from my grandson!’”

Cenac would soon cut his teeth as a staff writer for King of the Hill, an animated sitcom about a conservative Texas father and the encroaching liberal culture he struggles to adjust to. On his first day, the staff were workshopping an episode in which a former Dallas Cowboy moves onto Hank Hill’s street. Cenac coincidently related to the plot: while he was living in Dallas as a child, a special teams football player for the Cowboys moved across the street, and his neighborhood “lost their minds.” In a room full of Harvard grads writing dialogue for a Reagan-obsessed white father and his working class family, Cenac found he could actually relate to Hank the most. He credits this time in animation, specifically, with his ability to see stories from perspectives other than his own, to put himself behind someone else’s eyes. “I had this real sense of confidence,” he says. “Oh right, we’re just telling stories about a family in Texas.”

[caption id="attachment_id_286621"]  Krista Schlueter for Spin[/caption]

Krista Schlueter for Spin[/caption]

The first episode of Problem Areas opens with two fast-paced segments on billionaires like Elon Musk mass-exiting earth, and the science behind “poop” as a source of natural energy. “It feels like we’ve learned a lot more about each other,” he says to the camera around seven minutes in. “I know that you shit, and guess what, I shit too. So why don’t we get deeper?” Cenac then dives into a report on policing reform in the wake of the murder of Philando Castille, who in 2016 was killed in his car after complying with an officer during a traffic stop in St. Paul, Minnesota.

The transition between the two is unavoidably jarring, funny as the jokes may be; Cenac announces that the show will cover policing in America across ten episodes, and the camera jerks away as if our viewer is about to bolt for the door, before he exasperatingly pulls it back. “I’m not saying all this to bum you out. Look, we just met, I barely remember your name,” he quips. Still, the show’s creator seems keenly attuned to the perception of another black comic discussing police brutality, and all the potential viewers who may write the show off early. “It’s easy to think that I was making the camera a white person in that moment,” he explains. “[But] for people who live in a neighborhood where they are constantly being policed in a way that’s detrimental to their society, they don’t wanna hear shit they already know,” he continues, pointedly. “Come at me when you got answers.”

https://www.youtube.com/embed/dCYRxTvxE9g

Cenac takes on the project by earnestly playing the part of an Average Joe seeking information about modern policing from experts that include officers, politicians, community organizers, professors, and students, who bring first-hand accounts and impartial expertise to the circumstances of Castille’s death. New York City Mayor Bill DeBlasio, Black Live Matters affiliate Chauntyll Allen, and Peter Moskos, a former Baltimore police officer and professor at John Jay College of Criminal Justice, make appearances in the episode about police training in St. Paul. There’s little fluff: the show’s cameras go into precincts and city halls across the country, and the subjects deliver illuminating, truly informative interviews about hiring practices and character screening. By exposing audiences to how policing currently works behind the curtain, Cenac aims to reveal areas in which policing may be improved, a solution-oriented approach to the conversation that has largely escaped public discourse. “Monsters aren’t as scary if you start shining lights on them,” he says.

One of the episode’s best bits digs up examples of internal police training, which includes a cultural diversity class, a video game that simulates traffic stops turned violent, and a self-described “killology” expert, who helps officers desensitize themselves to the prospect of violence with promises that, after killing a bad guy, they’ll have “the best sex they had in months.” Cenac cuts in right on time, offering up less bloody roads to great sex: “What about a Sade record? Or eye contact?”

“From the very start, he wanted to be an observer of the stories,” Diane Fitzgerald, a producer on the show, says. “I don’t think he wanted to inject himself.” To achieve an even perspective, Cenac reached out to staffers he thought were “hopeful,” and culled together a writing room repeatedly described to me by those I talked to as “diverse.” Producer Hallie Haglund recalls that he wanted to create “something that felt a little like a response to people’s despair at the current political moment.” Haglund continues: “Wyatt is an incredibly compassionate person that has empathy for people on either side of a topic.” When discussing policing, this means the side of the folks who think police should be criticized for their use of force as a tool of the state, and those who think they should be celebrated for the risks they take to serve and protect. The series strikes a fine balance, one that most contemporary political comedy must aspire to: no matter how heinous a headline politics serves up, is there a joke that can soften its blow? Can humor be used as a salve to get to the root of issues more quickly, or forge common grounds more frequently?

When I ask if he considered how speaking out against police violence might affect his career, he shrugs. “After I left the Daily Show, I was kind of sitting out for five years,” he says. “I know what it’s like to not be able to have that platform for my voice the way I want it. This is my opportunity… I’m not gonna allow my ego to make me feel entitled enough that I’m guaranteed another opportunity.”

[caption id="attachment_id_286626"]  Krista Schlueter for Spin[/caption]

Krista Schlueter for Spin[/caption]

The Problem Areas staff that I spoke to say they are most excited about the show's format, which bucks familiar traits like a studio audience and special guests in favor of a more intimate tone. “One of the things that I was thinking about was the Serial podcast,” Cenac says. “They did such an amazing job of telling this real time story and getting people invested in it in a way that you had people going out into the woods trying to solve this case, trying to exonerate Adnan. If people are doing that for a true crime story—is there a way to serialize a social issue?”

The question comes back to the idea that news cycle is often so chaotic that the core issue is lost to speed. “There are real lives and real consequences that are being forgotten,” he says. “When I watched the coverage of Ferguson,” he continues, “the footprint that the media took up, moving into a place like Ferguson for as long as they did... and when the story is done, they all pull up stakes. Only a few national journalists go back. What is the impact of giving a place that much attention, and then taking it away?”

For now, the Problem Areas remains a rolling experiment in humor and human interest, a show about the lightning rod hot-topic of policing with a script that allows the light, monotonic voices of Alexa and Siri to chime as eavesdropping passersby that fact-check and prod its host. Cenac hasn’t yet had his wave of pop adulation, nor a controversial departure from the spotlight. While peers like Jon Oliver and Samantha Bee have extended their profiles through a similar route, Cenac’s future is likely to be similarly defined by this new creation. In any case, by pointing his resources and capabilities explicitly toward measurable change, he’ll fall on the right side of history, no matter the series’ fate. Problem Areas feels like a vision of tomorrow’s political comedy, concerned with poking fun at polarization altogether. “It’s very easy to want to burn it all down and rebuild,” Cenac tells me. “It’s a lot harder to get the gasoline.”