When he was in third grade, his mother Alice died from a heart attack, and he was raised by his father Solomon, who four years later also died of a heart attack. Thirteen-year-old orphan Tracy was sent to live first with an aunt nearby, then, propitiously, with an aunt in California, in View Park-Windsor Hills, a predominantly Black, upper-middle class neighborhood in South Central Los Angeles.

By eighth grade, he had moved to Crenshaw, where he attended Palms Junior High, a predominantly white school. From there he went to Crenshaw High School, where he got his first exposure to gangs. Crips and Bloods stalked the halls, forming a gauntlet repeated across South Central. Although never inducted, the future gangsta rapper was “affiliated” with the Crips. And he did petty crime to make extra cash on top of the social security benefits he started receiving at 17 from his father’s death.

Crenshaw High was where Tracy had his first experience performing music, joining a group called, quaintly, The Precious Few of Crenshaw High School. At 18, he became a father.

After high school Tracy went into the Army, joining the 25th Infantry, where he discovered hip-hop when he heard one of his fellow soldiers blasting “Rapper’s Delight” by The Sugarhill Gang. Something clicked — maybe, he thought, he could go back to Los Angeles and start throwing rap parties in the same vein as local electro pioneers Uncle Jamm’s Army, who were famously minting money at the time.

It worked out better than that, as you know. He was the foremost pioneer of the West Coast gangsta rap sound. But he had more to say than just gangsta, and, like Public Enemy later on the East Coast, waxed politically, releasing the rebellious anthem, “Killers” in 1984.

“A man took an ad on T.V. / To enroll in the police academy,” he raps on the song. “He’s very talented, outstanding proof / From his clean-cut appearance to the shine on his boots / When it comes to graduation, he's number one / An expert with a rifle and also a gun / Three weeks on the beat and his weak nerves crack / And fires four warning shots into a kid's back.”

You could call it prophetic.

His professional moniker came from a nickname his friends gave him when he got home from the army. He would entertain them by accurately reciting memorized passages of novels written by Iceberg Slim (itself a professional moniker, for a pimp-turned-writer called Robert Beck). His friends, who called Tracy “T,” would say “Kick some more of that Ice, T.”

In 1986, when rap was young, and still outside the mainstream, Ice-T released “6 ’N The Mornin’,” riddled with real accounts of criminal life. It was a big hit. A year later, he had a major label deal with Sire Records and a hot debut album, Rhyme Pays. It sold 500,000 copies, a huge amount for a rap record at the time.

His next album, Power, came out in 1988 and furthered his trajectory, but it was 1991’s O.G. Original Gangster, his fourth album, that defined the era and made Ice-T the undisputed godfather of gangsta rap. With songs such as “Escape from the Killing Fields,” a powerful rewrite of Public Enemy’s “Black Steel in the Hour of Chaos,” and the Grammy-nominated “New Jack Hustler (Nino’s Theme),” featured in New Jack City, the 24-song LP painted a vivid picture of the carnage and devastation that comes from a life of crime.

Part of what made Original Gangster so intriguing was its musical diversity. The way he rhymed on “Mind Over Matter” differed greatly from his cadence on “Mic Contract,” and what he did on “Body Count” — which he later adopted for the name of his rap-metal group — was the polar opposite of what he did on the spellbinding, chilling, spoken word track “Ya Shoulda Killed Me Last Year.”

Less than a year later, Body Count, the band, would substantially ruffle the feathers of police everywhere, the National Rifle Association, Time Warner Board member and NRA shill Charlton Heston, and CLEAT (Combined Law Enforcement Associations of Texas) with the release of the controversial, vastly misinterpreted “Cop Killer.” A song built on (understandable) rage, “Cop Killer” sparked boycotts across the country and precipitated Warner Music, buckling under the pressure, dropping Ice-T (and, trivia note, parent company Time Warner jettisoning Vibe magazine, because, you know, all those rappers look the same…).

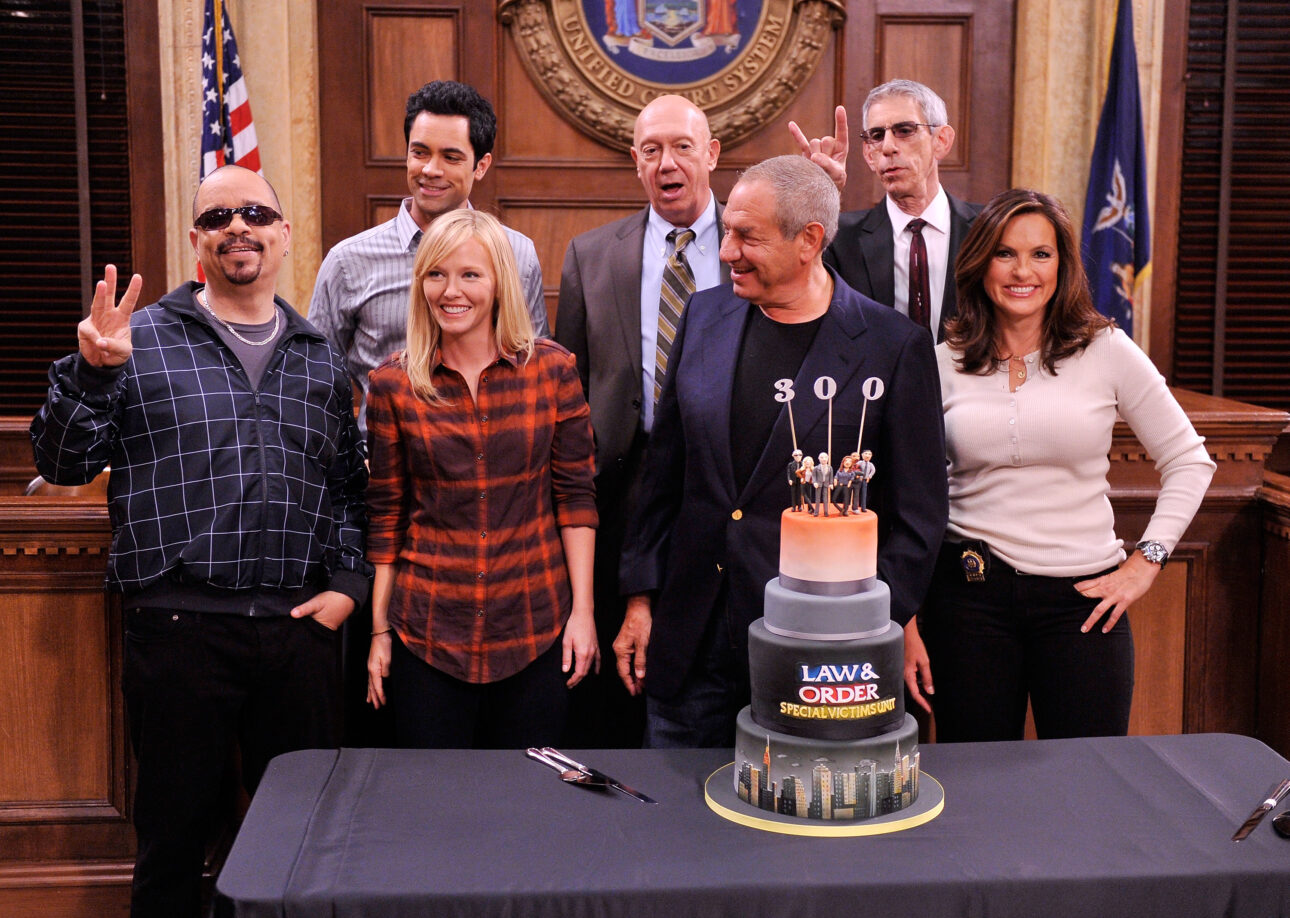

For the last 24 years (while still releasing music), Ice-T has played Detective Odafin Tutuola on TV’s longest-running police drama, Law & Order: Special Victims Unit. He got his first acting role in Breakin’ in 1984, when hip-hop was an exotic animal to most of America, and Ice was just in the right place at the right time. He had a more meaningful role in Mario Van Peebles’s classic New Jack City, as Detective Scotty Appleton.

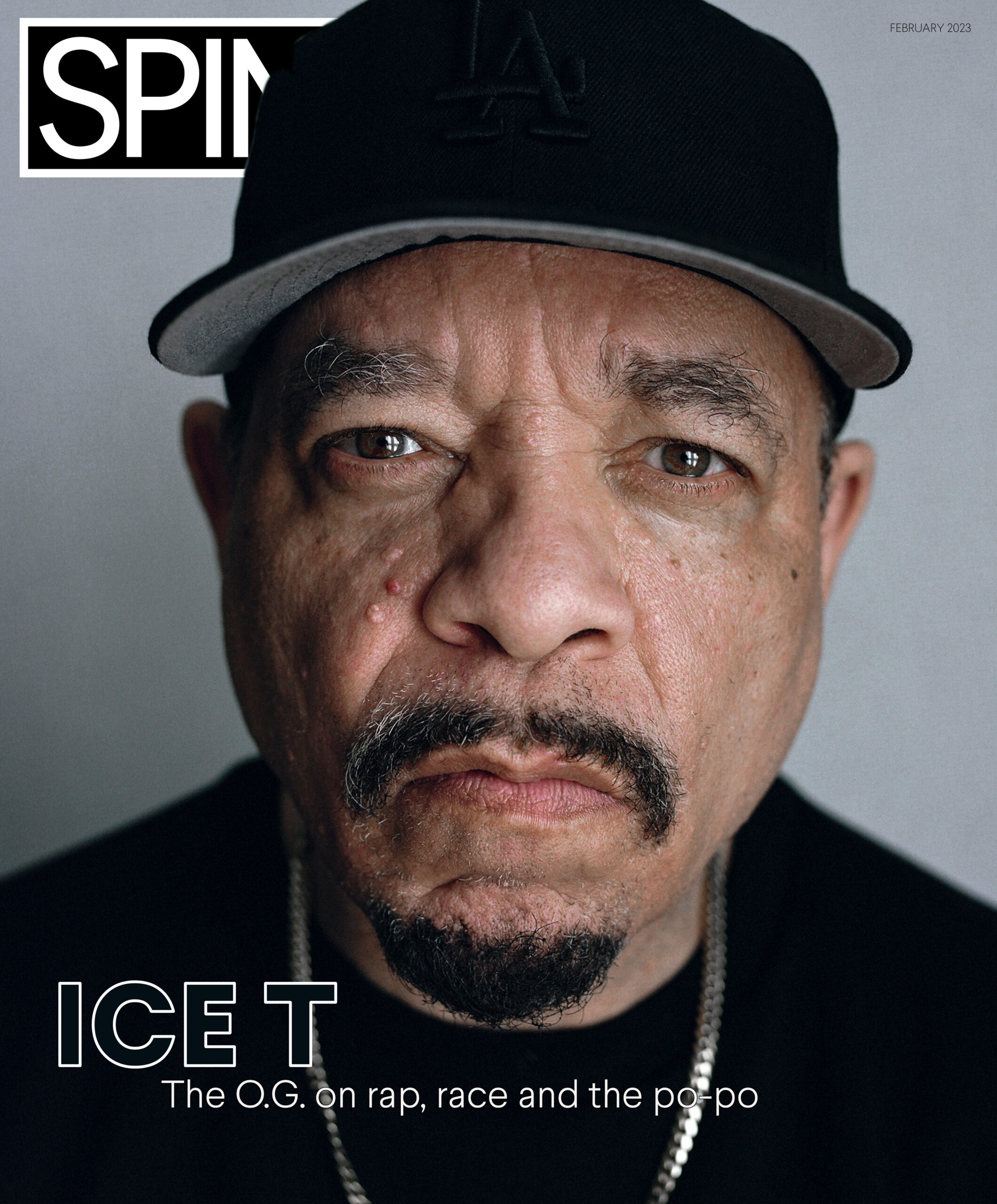

In 2018, Body Count won a Grammy Award in the Best Metal Performance category, for “Black Hoodie.” And on Feb. 5th this year, he performed at the Grammys with other rap immortals, in a slightly early celebration of hip-hop’s 50th anniversary. On Feb. 17th., a day after his 65th birthday, when he can officially start receiving his own social security benefits, he’ll get his star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame.

I interviewed him for this cover story at the toney and very discreet L’Ermitage Hotel in Beverly Hills, the day after his Grammy’s appearance.

When did you realize you had a talent for rapping?

I used to write raps for the gangs in high school. I would write little slogans and raps for them before I even knew what hip-hop was. Saying rhymes has always been a part of Black culture. Hustlers would call it toasting.

Saying rhymes was something I knew how to do in high school, so when I went into the military after I got out of school, that's where I got turned on to hip-hop, because I was in there with cats from New York, and they had tapes and they were playing this new music and I was like, “What is this, you?” The first generation of hip-hop is unrecorded or tape-recorded hip-hop, before anyone ever made a record.

We're talking the DJ Hollywood era.

Right. But there was tapes going around of hip-hop and parties, so I got a taste of it very, very early. And then “King Tim III” by The Fatback Band came out, and they were rapping. Teena Marie had a little rap on a record, and then Sugarhill Gang came out. When that came out, I felt like I could do it, because I already had been writing rhymes. But my intention was to come out of the Army and throw parties. I had gotten a lot of stereo equipment in the military. I bought a bunch of equipment, and that was my plan — to come back and actually be like Uncle Jamm’s Army. There was a big underage a scene in L.A., like people who are 18 that aren't 21 who still want to party. So that's where those dances came in. That's what the scene was in L.A, and there was tons of money being made. Uncle Jamm’s was able to fill the L.A. Sports Arena several times. Like what a rave is now, yeah, they were doing it.

Also Read

Chuck D Shows Us How to Rage With Age

Egyptian Lover was one of the DJs, Bob Cat was a DJ, and I was the one of the only people they would let rap. I just started to get more attention from rapping than carrying all that equipment around. I hooked up with Evil and Henry, they were called the New York City Spin Masters, and they were some of the earliest DJs on the West Coast that could scratch, because they were really from Brooklyn. I saw them at a show, and I introduced myself and I said, “Man, you know, I want to go with you to your parties.” And they would hit three or four different house parties or situations at night. On the flyers, there would be four or five DJ crews. So they would go from one to the other. They wouldn't just stay at one. And I started traveling with them, and I would jump on and MC.

That’s how I started rapping around L.A.

Your first single, “The Coldest Rap/Cold Wind-Madness,” in 1983, preceded the World Class Wreckin' Cru with Dr. Dre and Egyptian Lover’s first album, On The Nile. Tell us about that time.

There’s not nobody in L.A. that’s gonna say Ice-T wasn't first. There was other people out there at the time. There were groups like Disco Daddy and Captain Rap, but there wasn’t more serious music where people were like, “OK, this is cool.” My first record was done…I was at a beauty parlor called Good Fred’s — this is when I had the perm — and I would say rhymes to the girls, just rapping. A guy named Willie Strong walked in, and he owned VIP Records, the famous record store Snoop Dogg stood on in the “Doggystyle” video. It’s one of the most famous record stores in L.A. They had what they called Saturn Records. I don’t think any other record ever came out on Saturn Records. I think they created that label just for me. They said, “You want to make a record?” And I was like, “Sure.”

It was kind of like Run’s lyric: “So Larry put me inside his Cadillac / The chauffeur drove off, and we never came back.”

I went to this recording studio, and they had this music by Jimmy Jam and Terry Lewis, and there was some people singing on the track. They pulled the vocals down and said, “rap.” And I basically made “The Coldest Rap” with all the raps I had in my head, like my walking-around raps and stuff I was saying to the girls.

I made a hook on the spot: “I’m a player, that’s all I know / On a summer day, I play in the snow,” which is a cocaine reference. “From the womb to the tomb, I run my game / I'm cold as ice, and I show no shame.” I made that up on the spot. “The ladies say I was heaven sent ‘cause I got more money than the U.S. Mint” — stuff I was already saying. That was “The Coldest Rap.” It was done in one take, and they said, “Cool.” I think I made maybe two, three hundred dollars on that record.

Well, you were getting paid for music. That had to be pretty cool.

At that time, there were no real rap scene, and it just put me in the game out here. That record led to me going to the Radio Club. There’s a guy that ran the Radio Club called Alex Jordan, or A.J., and another white cat called KK, basically by way of New York. They said, “Ice-T is the only person who got a rap record. Will he come and perform at this club?” I get a call and I'm like, “Yeah,” and I went there. That was a big moment because I walked into that club and everyone in that club knew my record.

See, what happens is, if they play your music in a particular place like a restaurant or a club every night, you become a star in that room. No one else knows it, but at that particular place, you're hot. And that was a moment where I went in there, I did my song, and everyone knew every word to that record. That was my first real taste of what fame was. I was like, “Oh, shit!”

Now, no one else on Earth knew two words to that record, but in that club, I was hot. That club was a cross of the upscale white kids that were just touching the hot hip-hop.

People were there like Malcolm McLaren. Madonna came in. I actually put Madonna on the stage. I had become the stage manager because I came there so much. They said, “Hey, you can run the rappers? Take them downstairs, audition them?” So Madonna came in, and they were like, “This is some new chick.” She had a single called “Physical Attraction.” There's a picture of me standing on stage with Madonna way back when she was a kid. She did well that night.

That’s where I started, and that led to being in the movie Breakin’. They had heard about this hip-hop scene that was popping in MacArthur Park at the Radio Club. They came in there and said, “We’re gonna use you guys as the dancers” — that’s where Shrimp and Shabba Doo and all them got picked up — “and you could be the rapper.” Then they gave us a chance to make a song, and we made “Reckless” [featuring Chris “The Glove” Taylor]. Eminem said that's the first rap record he ever heard.

“Killers” came out right after “Reckless.”

And what happened to “Reckless Rivalry” that was in Breakin’ 2? It remains unreleased as I understand.

Yeah, that was just a movie song. That was a song called “Go Off.” But The Glove and Afrika Islam scratching on it. Yeah, we need to hunt that record down! There was another record I did called “Combat” they still use in breaking competitions.

“Killers” is often considered your first political rap. What made you change course?

“Killers” was my version of Run-DMC, because I rap back and forth to myself like it was two rappers. So I rap one way, then the second verse sounded like how Run and them would rap. I think it was just coming off songs like “It's Like That” and “Hard Times” that had a little political undertone and things of that nature. I think that inspired me to do those songs.

I didn't start rapping until I was 27. It wasn’t like I started late, I was just that old when hip-hop started.

Was the Army where you realized you didn’t want to be entangled in street life anymore?

The Army wasn’t what made me want to get out of gang life. I was aware of gang life when I was in high school. At that point, I realized if you become part of a set, you immediately turn yourself into the enemy of the rest of the city. You're not in a gang, you’re from a gang. I wasn’t living in any of the neighborhoods that really had gangs. I was living in a View Park, which is like an upper middle class Black area above Crenshaw, on the west side. So I would go to Crenshaw, and that's where the gangs was, but I'm not from any of their neighborhoods. Now, Crenshaw is mostly connected to Rollin’ 60s. When I went there, they had Eight Tray Gangsters, Hoover Crips, Harlem Crips, which is the 30s, and they had some Bloods there.

I was just like, I can be affiliated with these gangs, but there's no way I should jump into no set because I'm not from they neighborhoods. I was aware of gang banging and understood the principles of it. Near the end of high school, I started hanging out with the hustlers and cats that were more about getting money, right? That's a whole other click of cats.

But when I came out in the Army, I was brought back into the crime world because my boys who were like small-time criminals when I left had now elevated to jewelry heists, and they had elevated to all kinds of other types of crimes. So I just fell back in with them. I'm doing that and on the weekends, I'm doing the rap shit.

At some point, you got into a car accident. You were admitted as a John Doe, right? Due to criminal activity you didn’t carry an ID.

Right when I was getting ready to get into hip-hop, I was still in the streets. I was making money hustling. I went to a club called Carolina West. It went from 9 p.m. to 9 a.m. Everybody knows when you come out of those clubs, your eyes aren’t working. Well, here I go, and I decided to drive home. I would close my eyes at the corner or at a stoplight, which is a bad idea. You can't close your eyes when you're in a car. I fell asleep and rolled right into an intersection. I was in a Porsche, got hit, and I was ejected into the passenger seat. Thank God I didn't have on a seatbelt because the accident broke the steering wheel off of the car, but I went into the passenger seat, so that put me in the hospital for 10 weeks. I had a broken pelvis, a broken femur, a broken foot — the whole left side of my body was smashed.

And they John Doe’d me ‘cause I didn't have an ID. When you in the streets hustling, you don't carry ID because you want to cap aliases so you can keep it moving. I didn't have that, and they didn't know who I was. I went to the county hospital and was in a bad position. Then one of my friend’s mothers was like, “Where’s Tracy? Where he at? We ain't seen him.” And she found me in the hospital some kind of way, and said, “Well, he's a vet.” She got me moved to a Veterans Hospital in Westwood, where it was much better, and I was able to heal.

How did that affect you mentally and emotionally? The D.O.C. fell asleep at the wheel, lost his voice, and his rapping career was over.

It just changed my life as far as what I was doing hustling ‘cause a lot of the stuff we were doing was basically parkour. We would take the jewels, and you’d have to catch us. It was very athletic and stuff, jumping over cats. So now I can't move, I can't run. It made me slow down a lot and forced me to focus on music. But no one had never made any money in music yet. Run and them hadn't even really bought cars yet. I’m coming from a zone where it's like, “Why you want to rap, man? You better get this money. Like, who the fuck wants to rap?" Like Grandmaster Flash said the other night [at the Grammys], this was just something that was entertainment for us. It was a pastime. It was not something you do to get paid. No one ever was gonna be a celebrity doing this shit.

How did losing both of your parents so young affect your ambition?

I think what happens when you lose your parents young, you just realize there's nobody to fall back on. There's no one who's supposed to take care of you. I think when I lost my moms in the third grade, I didn't get really cry or nothing. I didn't get it.

I'm from the age when you're a kid and somebody passes, they just take you off to the side, you end up with an aunt some place. You don't go to the funeral, you don't see nothing. You’re just isolated. And then I was with my pops for a while, and then in seventh grade when he passed, I was more like, “What’s going to happen to me?” They shipped me out to L.A. to live with his sister. And she was kind of like, “I'm taking care of you because I got to.” I knew early in life I was on my own. I don't have no brothers and sisters. I just realized there was no where to fall back to.

If I was fucked up, I was truly homeless. I was truly out there. And I got a lot of pride, so I would never would celebrate Christmas or any family holidays because I didn’t want to be in anyone else’s house over their holidays. That wasn’t my place to be in your Thanksgiving bullshit. So I ate a lot of Thanksgiving dinners at Denny’s and hamburger spots.

That kind of makes me sad, Ice.

It’s nothing to be sad about. It’s like, you can look at a poor person and be sad for him, but then to them it's their reality, so I don't feel any special way. And honestly, I went through what a lot of people my age still haven’t. They've still have their their parents. They’re still about to go through it. I got past that hump early.

Do you still think about your parents?

No. I was too young. What am I going to think about? My mother died when I was in third grade. I can't remember that much about her. I remember the night she died. I remember that. And then my father, I remember him disciplining me, but no, I don't think about them.

“6 ’N The Mornin’” was inspired by the Schoolly D single, “P.S.K. What Does It Mean?” It was made with a Roland TR-808. Tell us about making that song?

It was just me on the beat. My buddy Randy and I were messing with the 808. I had been inspired by Schoolly D, of course, because he changed the format when he sang about a gang. And I was like, “Oh, shit!” I didn't know that was OK. But when he did that, I said, “OK.” Like I said, I used to make these gangster raps, and so my boy was like, "Say that shit you be saying when it’s just us fucking around.”

There was a record by Beastie Boys called “Hold It Now, Hit It.” And it had this weird break in the song where it was like, “Hey, Leroy!” And then it came back on. So “6 ’N The Mornin,'” I wanted a break that had nothing to do with the record. That was what kind of influenced the way the beat was created, to where it would stop and then start. You know, “Word.” That was from the Beastie Boys.

I read that Licensed To Ill is one of your favorite albums.

Real talk. We’re all influenced by different things. So you say, “Man, I want to record what that does.” When we made the song, it was B-Side to a song called “Dog'n The Wax.” I made a record called “You Don't Quit” with Unknown DJ on Techno Hop Records. I was trying to get him to do one with Henry and Evil E, my DJs. And he was like, “Nah, you gotta give me another record.” So I did that. And then the B-Side was “6 ’N The Mornin’,”and like Chuck D says, the B-Side wins again.

It was a hit. We didn't look at it like a hit, but it hit.

Would you say that is what opened the floodgates to albums like Rhymes Pays and rapping about gang life, street life?

Oh, it opened up the floodgates to up my life and my ability to talk about things that I was comfortable with. You got to understand, early on, it was like, if I’mma rap, I'm feeling like I gotta rap about parties and shit. I didn't know how long I was going to be able to rap about that stuff because there's only so much content to that. But when they finally said, “Oh, OK. We can rock with this,” I’m like, “Oh, shit. They want to hear this shit?” If you listen to early records, I’m just beating around the bush with hip-hop.

And that was kind of the point you made in the LL Cool J feud — how many times can you say you're “bad” in one song?

Right, right, right. I always compare it to making a peanut butter and jelly sandwich. If I came over your house, you made a peanut butter and jelly sandwich, I ate it and I go, “Wow, this is so good, you should sell it.” You’re like, “Sell this?” You sell it and it’s a big hit. That’s how gangsta rap fell in my life ‘cause I got all these experiences, criminal shit I've been through, but I didn’t think it was available to use in music.

Then when I hit with “6 ’N The Mornin’,” I'm like, “Oh, this is gonna be easy. I’m in now.” Now, I know what they want to hear and I got a million of this shit. That was the birth of Ice-T. You know?

If you look at me in Breakin’, I'm trying to rap like rappers, like hip-hoppers. I'm trying to dress like them. One of the big moments in my life as far as how I looked was Russell Simmons. I did a party and I was in the crowd at a place called Casa Camino Real, and I was in my street clothes, you know, the way I dress. They called me on the stage, I got up there and I did my thing. Russell said, “That’s your look, man.” He said, “You ain't got to dress up like no rapper.” He said, “Just come out like that. They want to see that L.A. style. Do your shit.” And that's when I started back wearing the Fila and all the fly shit, you know?

I thought I had to dress like Melle Mel and them because I'm trying to be part of hip-hop. But Russell was like, “Nah, fuck that. Be you.”

Looking at older videos, you do look pretty cool, especially in “I’m Your Pusher.”

That's dressing like a L.A. drug dealer, but a rapper didn't dress like that.

In 1990, when you formed Body Count, Charlton Heston attacked you for making “violent” music, and caused Warner Bros Records to drop you from the label. At the exact same time, as the NRA spokesman, he was advocating for approval for a bullet nicknamed the “Cop Killer,” because it pierced police officers’ kevlar shields.

How ironic is that?

What was your reaction at the time, and how did you handle that?

We really didn't give a fuck about Charlton Heston. He was the least of our problems. I mean, we didn't give a fuck about him at all. I thought he was just trying to get publicity, you know, he's an actor. We were dealing with the real cops and the real government, people like that. That whole “Cop Killer” shit just went out of control. It started with one thing, and the next thing you know, I'm on the news with the president and I'm like, “Lord have mercy.” In the meantime, Black Flag had been making records about cops like “Police Story.” You got rock groups called Millions of Dead Cops. It was kind of like a weird moment where we were catching a lot of heat for something we didn't even think was so bad.

You suddenly became a target.

Yeah. We’re just doing rock music. We’re just talking that shit. They thought it was a call-to-action to kill police, and it couldn't have been further from that. It was a song about rage, somebody mad enough to go after the cops, a cop killer based on police brutality. But they were like, “You’re trying to tell people to go do it.”

See, they think rappers and Black people aren't capable of making art. You have to be that angry Black man. I'm not trying to kill no police. That was just a minute in time where they were just out of control and they were going after our head. It was supposed to be over for me at that point. They were trying to blackball me and blacklist me. I was never really worried about the cops as much as I was worried about running into a cop lover.

Oh, what would be the Blue Lives Matter guys today?

Anybody. You’re in a restaurant and you run into somebody who’s like, “My Dad’s a cop,” and they want to start some shit.

Did that ever happen?

No, no, it didn’t, but it could happen. And that's what happens with any kind of beef. Say for instance me and Method Man were fighting — which, Meth is one of my best friends — but for me to say that, I could run into some Wu-Tang Clan people and they like, “Oh, you got problems with Meth?” You can end up in some shit or an altercation. Whenever you got beef out there, you don't know how it's gonna come back at you.

In 1991, there was the Rodney King beating and the L.A. Riots. In 2023, the horrific police killing of Tyre Nichols in Memphis. Has anything really changed?

Only thing that’s changed is camera phones. Right now you're seeing it — that’s it. The same bullshit’s going on. I think cops are slightly a little bit more accountable because they know they’re being watched, but they still get off. It’s too much power. Until they put one of these cops on death row and let ‘em know people aren’t having it… from being a cop all this time on TV, I’ve figured it out. They fuck over who they think they can get away with fucking over. They fuck over people they think can’t fight back. When we’re on Law & Order and they go, “Oh, they're from the Upper East Side. Tread lightly," what they're really saying is these people got money and they can sue the shit out of us.

But if you're in the projects, it can go any kind of way because they can't do nothing. “Lay him on the ground, treat him like shit.” Only if you look up and say, “My father is the District Attorney,” you're not going to lay on that ground because they know you can fight back. They take advantage of people they don't think can fight back. It's not as much racism as, “Who can I get over on?” And like I said in “No Lives Matter,” Black and brown skin has always stood for poor.

But they’re not laying people down in gay communities. They’re not doing that. At the end of the day, they know who they're fucking with, you know what I'm saying? Don’t get me wrong — you could run into some racist cops out there. There’s racist people all over the world, but it's not that simple. It's like you saw those Black cops whip on that man in Memphis. They did it because they felt they could get away with it.

Do you think it was because of their race?

They got caught out there doing some dumb shit because apparently he was messing with one their girls, but I don’t know what the fuck they were thinking about. They knew they were getting filmed — like, what the fuck? It’s abuse of power. That’s all it is. When people say, “Ice, you don’t like cops.” Nah, I don’t like bullies. I don’t like racists. I don’t give a fuck what you are or what your job is. That’s it. Period. I’m not judging you because you’re the police.

You mentioned your Body Count song “No Lives Matter.” What do you think about the Black Lives Matter movement? Has it been effective?

I think the term has been effective. I don’t really know, ‘cause anything that’s moving positive, they’re gonna try to take it apart and say, “Oh, this is a problem, and the money’s not going here or there.”

I'm not connected to the organization, Black Lives Matter. I don't even know who runs it. I don't even know what their agenda is, but I have connected with the term. I heard a comedian say, “Can we just matter?” We matter. Black lives are important. Black lives matter. I mean, goddammit, can we have a little bit of something? Shit. Dogs' lives matter. You know? It’s the very least, and people are pissed at it. I tried to make it clear in my song that if we were talking about gay people, if that was the problem, then that would be the slogan. But right now, we talking about Black lives or women’s lives, if that's the topic. But don’t be mad. Don't try to claim every motherfuckin’ thing. Can we have the word? God damn!

Here we are, it’s Black History Month. What has hip-hop done well? Is there anything to improve?

I don’t know really if it can improve. Hip-hop just evolves, and it's just gonna continue to evolve. It'll fuck up. It'll right itself. Like any other organism, you know?

What has hip-hop done for you?

I like to say it saved my life because it derailed me from what I was doing, which was negative, and it gave me a chance to do something positive. Once I found out that just being me was a brand, I was able to express myself. Whereas somebody like Public Enemy comes from this militant area, gangsta rap is the person saying, “I'm done asking for your help. Fuck you. I'm gonna take it. I'm gonna do it myself.” If anybody goes, “Oh, well, that's bad?” Well, let's bring up the Kennedys or let's bring up the mafia. Like every motherfucker that came over here, some people weren't handed shit and they just had to go get it. So that gangster is absolutely negative. After some point people go, “You know what, I'm tired of marching. Yeah, we ready to get gangster.”

It goes into another type of energy. So when they saw N.W.A and us come, they were like, “Oh shit, these are motherfuckers that really ain't asking for help. They're going to take it.” And that energy is needed. We don't have to want to fight nobody. Somebody asked me one time, “What is gangsta? What is your gangsta?” I said, “I don't back up well.”

That’s a great answer.

I’m not out here trying to push the line. I’m not out here trying to do something, but when you tell me what I can’t do “or else,” I’m not that guy. That’s what I’m about. I’m not trying to be a bad guy, but I don’t back up.

I was asked yesterday what someone can expect from you, just as a person. The first thing that came to my mind was the word “humble.” How do you stay grounded?

You know what it is, though? You get what you give. Some people, like yourself, are very pleasant to talk to. So that's what you get back. Other people aren’t, and I can give them that, too. You know what I mean? So some people are assholes, so I can play that game. You know, my thing is like, I'm as nice as you let me be.

I'm trying to be nice. But if you want to go that over there, I'm very seasoned in that area too. Like, if you want to get stupid, I’m very well versed in being a motherfucker and a bitch ass… I’ll go there worse than you've ever thought. You don't have to be like that to good people. And let me tell you, the most dangerous people I've ever met are the nicest people I've ever met. It’s not the guy who's always talking tough. It’s the guy who will pull a picture of his kids out, but during dinner could pull your fucking eye out of your fucking head.

I interview a lot of West Coast gangster rappers, and they are always the most polite, but you're not going to mess with them.

Because they got that switch they can turn on and off. Appreciate the fact it’s off. What people do is they want to poke it. They want to poke the lion. They want to see it and it’s like, “Why?” People meet me and they’ll say, "You’re so nice," and I’ll say, “Well, you're not my enemy.”

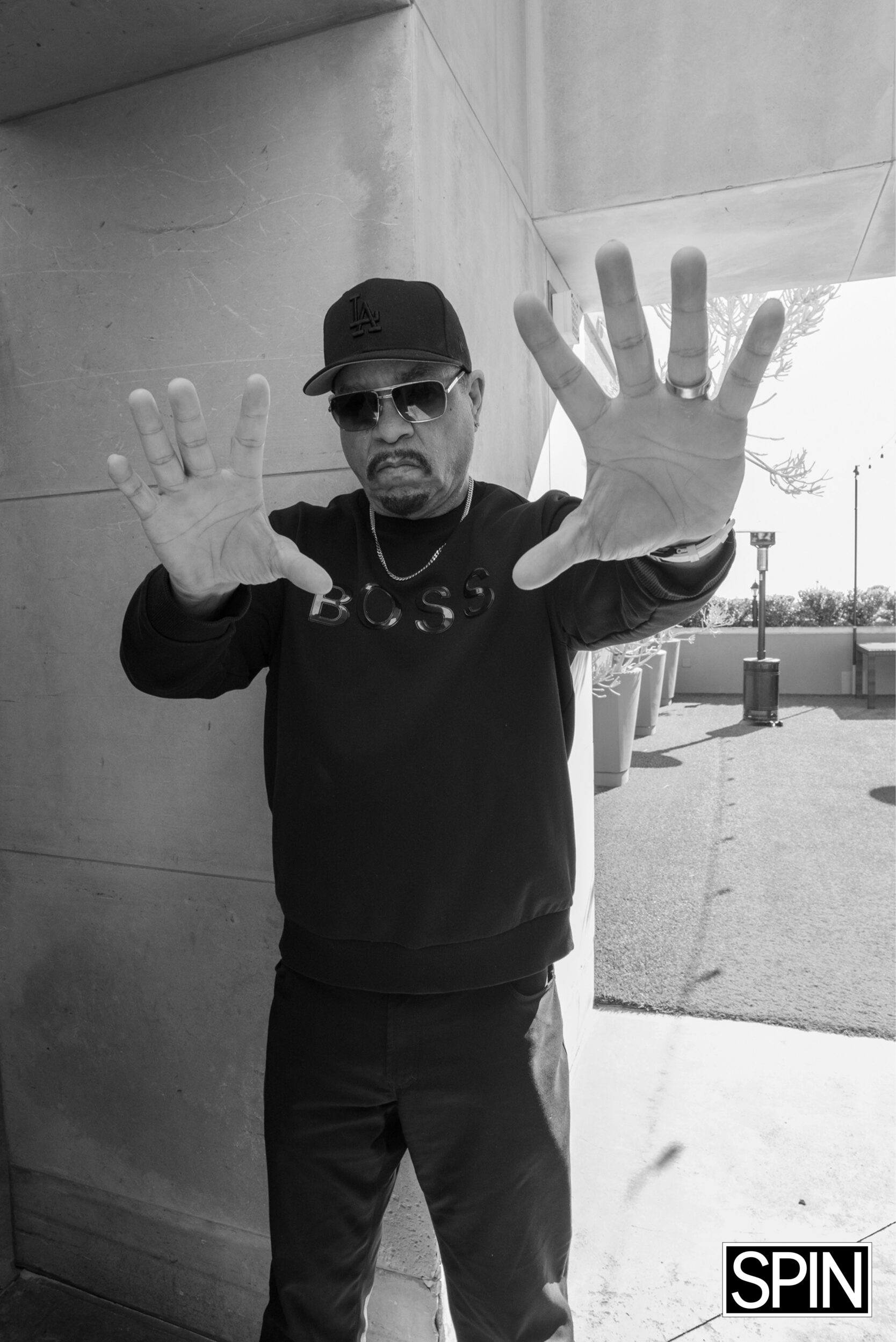

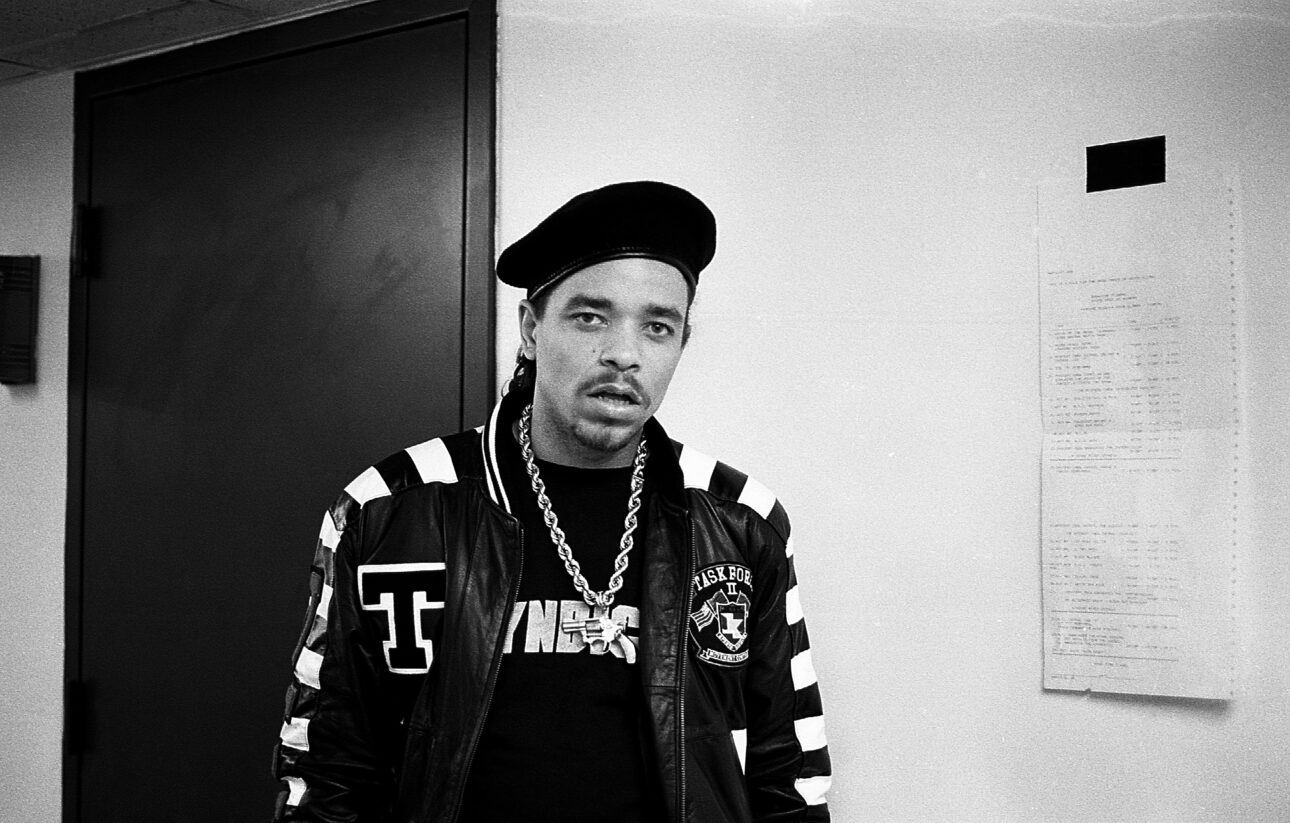

Photo Credit: Raymond Boyd

Photo Credit: Raymond Boyd

Photo Credit: Raymond Boyd

Photo Credit: Raymond Boyd

Photo Credit: Raymond Boyd

Photo Credit: Raymond Boyd

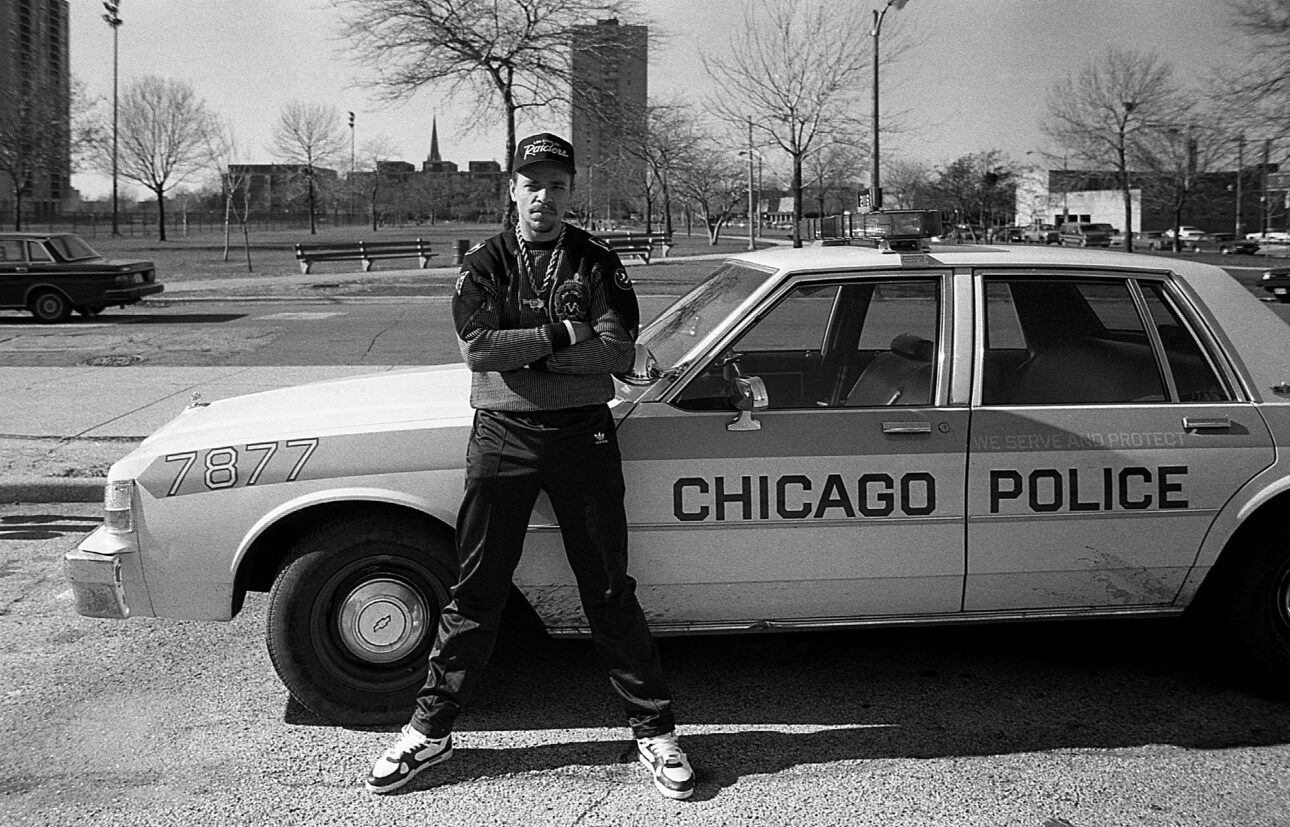

Photo Credit: Paul Natkin

Photo Credit: Paul Natkin

Photo Credit: Raymond Boyd

Photo Credit: Raymond Boyd

Photo Credit: Raymond Boyd

Photo Credit: Raymond Boyd

Photo Credit: Metal Hammer Magazine

Photo Credit: Metal Hammer Magazine

Photo Credit: Raymond Boyd

Photo Credit: Raymond Boyd

Photo Credit: Jose Perez/Bauer-Griffin

Photo Credit: Jose Perez/Bauer-Griffin

Photo Credit: Stephen Lovekin

Photo Credit: Stephen Lovekin