He learned to rock ‘n’ roll and to master the blues in the clubs of Austin, and for that he is forever grateful. He’s been championed by Eric Clapton, Buddy Guy, and generations of artistes of rock, blues, and soul, won Grammys, and hit the Billboard Top-10 album chart with three consecutive albums: 2012’s Blak and Blu, 2015’s The Story of Sonny Boy Slim, and 2019’s acclaimed This Land. It sent him around the world, and will again in 2024 behind his ambitious new album, JPEG RAW, releasing on March 22.

His friend and collaborator Jacob Sciba, who co-produced the new album with Clark, is a frequent visitor to the ranch. “We spend a lot of time sitting at his pond fishing,” says Sciba. “That’s what he’s really into, what gives him peace."

Gary tried out some big cities. He chased his future wife, Australian model Nicole Trunfio, to New York and lived there for three years. He loved the city but concluded, “I don’t know how to be a New Yorker. I don’t know how this works. I am a southerner through and through.” So they moved to Los Angeles, got a place in one of the canyons, and had some good times, but the end result was the same.

“I didn’t know how to do that either, and I didn’t feel comfortable faking it,” he says now. “I know how to speak to Texans in their face. I know who my core community is.”

On a Zoom call from his home studio, where JPEG RAW began taking shape in the first year of COVID, and amid other kinds of turmoil and unrest from nationwide protests, Black Lives Matter, far-out conspiracy theories, and a crazed presidential election, he is bearded in a purple sweater, a colorful knit cap pulled over the top of his brow. He’s relaxed and ready to talk about his new album, which incorporates influences and textures from West Africa to the Mississippi Delta, classic ‘70s soul to the forward-leaning beats he’s been creating since 1999.

On This Land, he went beyond the blues, with some of his edgiest guitar work and biting lyrics on racism and social justice, bad love and good. Like that record, JPEG RAW is a search for new sounds and ideas. It was a long time in the making, finishing in 2023, including a trip to Los Angeles for sessions with the funk deities Stevie Wonder and George Clinton. Clark says he only got the album’s final masters a few weeks ago.

He returned to his ranch after finishing his 2019 This Land tour and picking up three more Grammys in January 2020. His third child arrived that February. Gary had already planned to take a break after a busy year, figuring the next record would come soon enough. Then COVID hit and the music world came to a stop.

This gave him family time he would have missed on the road. He was present in new ways. “I enjoyed being home, and my kids got to really know me, not just the guy who pops in with a suitcase every couple of weeks,” he says. “That was really getting to me, sitting on airplanes going, ‘What the hell am I doing?’”

Under pandemic lockdown, as things grew “stressful and weird,” the first stirrings of JPEG RAW began. “I didn’t know if we were going to be on tour again. I didn’t know if the whole music business was going to shut down. So I was thinking of how I was going to pivot,” he says. “That was kind of my mindstate.”

He was restless. So every Thursday, after firing up brisket for a couple of days in his smoker, he’d have his band over for dinner, a few drinks, and some extended jamming in the studio. There was no project in mind.

“I just had these guys and my family. That was my community. So it became deeper than just popping up to the studio and hanging out, bashing out a couple of tunes,” Gary says now. “This is our Starship Enterprise, and we are going to maneuver this thing through whatever happens, you know?”

Those sessions amounted to the longest period of uninterrupted musical exploration Clark has enjoyed since he signed to Warner Bros. There were no phone calls from the label, no schedules to follow. When things began opening up again, Gary and his band hit the road in mid-2021, leaving their fresh recordings unfinished. His manager, Scooter Weintraub, called him to say that he risked losing the momentum that had just peaked with This Land.

It was time to finish a new album.

“So we got real serious last year,” Gary says. "It was just us working.” Joining him were longtime sidemen JJ Johnson on drums and the guitarist Zapata, and newer players Jon Deas on keyboards and bassist Elijah Ford.

For the album, he wanted the drums to sound like bluesman Willie “Big Eyes” Smith colliding with the visionary beat-maker J Dilla, and the bass to be a mix of Motown’s James Jamerson and hip-hop bassist/producer Mike Dean. His attitude was, “Let’s not worry about the guitars. Let’s do the whole sonic palette. The guitars will be an afterthought,” he recalls. “I don’t want to make a guitar record. I want to make a sonically unique, vast soundscape.”

The first piece he began crafting was “This is Who We Are,” on almost orchestral layers of homemade beats, built from sampling and sequencing on an MPC. “I wanted to shape this thing not like a blues band kind of thing: Let’s make all the noise. Let’s play with sound,” Gary says. “I have dreams like that."

As he did on his last record, he kicks off this one with the most explosive track at his disposal, with a fiery blend of West African rhythm and American soul on “Maktub.” It comes after a conversation Clark once had with Carlos Santana, who urged: “You’ve got to go global.” More inspiration came in records by the Mali artists Ali Farka Touré and Tinariwen that co-producer Sciba had been playing endlessly and Gary now describes jokingly as “brainwashing.”

(Later, Sciba will say, with a laugh, “I wasn’t brainwashing him! I was just gracefully encouraging him without saying anything. We had a good laugh about that.”)

Set to layers of guitar and frantic percussion, Clark isn’t doing a simple impression of West African grooves on the track, but weaving them into his own sound. He sings in a rush: “They’re comin’ through/They’re gunnin’ for you/We know the truth/So we’re makin’ moves ... Time for a new revolution/We gotta move.”

The song's title was suggested by one of its co-writers, cultural journalist Sama’an Ashrawi. Posting online recently, Ashrawi described “Maktub”—written in Arabic as مكتوب—as “a kind of destiny you must work towards, a trek along the cosmos that only ends well if you stay on the righteous path.”

The word resonated. “I just thought it was powerful,” Gary says, the “coming together of music to inspire, give hope, and hopefully some healing. It made sense to me.”

Growing up in Austin, he’d first heard songs like Bob Marley’s “Get Up, Stand Up” and Curtis Mayfield’s “Move On Up” without understanding their revolutionary intentions. Now they hit hard. “Maktub” is meant to add to that legacy.

“These songs were giving me hope and a feeling like, ‘Come on guys, we can do anything,’” Gary says. “I didn’t realize what that was doing to me. Music has a way of shaping the culture, the mind, the way we move forward, our social situations. To harness that in musical form is pretty cool.”

The album’s title song is named after digital photography terms, “JPEG RAW,” and meant to signify unaltered reality. The track transitions from “Maktub” with a quick jazzy run along the piano keys, then Clark’s searing guitar lines and a sample from the Jackson 5’s “Maria.” His vocal shifts from laid-back to impatient, packing the verses with words and hip-hop energy, if not actual rapping, as he describes love among grown-ups: “It’s all fun and games until the hangover/Pillow talk turns to real talk when that baby’s coming/I hope you feel the same way in the morning sober.”

The “JPEG RAW” metaphor is a natural choice: “I was a photography nerd in high school,” he says.

“I started taking pictures more, and I felt weird about it because at a certain point in my life, I felt like when I walked into a room, the cameras were on me, and I wanted to be the observer. I didn’t want to be the observed. It felt funny to me. So I’m taking my power back, goddamn it. I’m snapping these shots and I’m taking these moments for me.

“I like taking my camera out and catching an owl swooping down. That’s who I am,” he continues. “I’m chilling, man. I got my toes out. I’m smoking a spliff. I’m watching my kids play in the yard. That to me is the exciting shit. Not the lights and the being on stage. That’s cool, but I don’t think of me as that.”

He has turned the JPEG RAW title into an acronym, as a statement on the human condition: Jealousy, Pride, Ego, Greed and Rules, Alter Ego, Worlds.

Final vocals and overdubs for the album were done at Jacob Sciba’s studio in downtown Austin. “On a lot of levels,” the producer says, “his music is ‘jpeg raw’—it’s unfiltered. It’s not photoshopped. It’s the raw picture.”

At 9 years old, Gary Clark was already musically obsessed, with a little karaoke tape machine that allowed him to record his own voice (and the beats he created with his dad’s Casio keyboard) over songs by Boyz II Men and Stevie Ray Vaughan. Later on, after becoming interested in the guitar, he would go to the garage with a little sister on drums, an older sister on keyboards, and a cousin on the bass, and teach himself to play the blues and the Jackson 5 hit “ABC.”

They were encouraged to play by their father, Gary Sr., who the kids jokingly called “Joe Jackson,” after the notorious patriarch.

By the time he got to Austin High, Gary was a full-time music nerd: “I would go to the music hall and meet up with the other weirdo, anti-social music-loving kids who were insecure about loving this thing that wasn’t so popular. We would eat our lunch and we would share music.”

A kid showed him how to play the riff on Nirvana’s “Smells Like Teen Spirit.” Others introduced him to distortion and punk-ska, Weezer and Green Day. He became close friends with a neighborhood girl named Eve Monsees, who played him some reverbed-out surf guitar by Dick Dale.

“I also grew up doing classical music and learning about barbershop quartets and singing opera music and doing musical theater,” he says now. “I grew up with all that at such a young age that it was just all music to me.”

It was Eve Monsees who brought Gary to his first club gig, and both were soon embraced as teenage blues phenoms during regular appearances at the legendary Austin club Antone’s. In 2010, he was invited by Clapton to play at his Crossroads Guitar Festival in Chicago. He was signed to Warner Bros. Records by Lenny Waronker, and Blak and Blu followed in 2012. It netted him his first two Grammy nominations.

Many early fans saw him mainly as a next-generation champion of traditional blues. But his impulse is to push his music further.

“People want me to play traditional blues, and if I’m being honest, I can’t do it better than fucking Muddy Waters did it,” he says. “I can’t do it better than Buddy Guy did it. Nobody can play the blues like Albert King. I’ve been getting away with it. That’s cute.”

He knows that some of the fans who first embraced him at Antone’s and various blues festivals, and who bought his first two albums, want just that from him.

“Oh, absolutely. But … so?” he says with a laugh. “I’m a musician, and I’m an observer who takes and interprets, and if I’m only feeding myself the same thing I was feeding myself 15 years ago, then I don’t feel like I’m really living my life to its full potential. I’m not just hanging around the blues clubs anymore. I’m thankful for that time in my life and all those influences. They’re always here, and they’ll pop up every now and then—like in ‘Don’t Start.’ You want some blues? That’s Blues 2.0."

Clark had a searing onscreen turn as bluesman Arthur “Big Boy” Crudup performing “That’s All Right, Mama” in Baz Luhrmann’s Elvis. (In the film, little Elvis bears witness to Crudup in a roadhouse, and the boy is shook.) There is no question that Gary is a gifted bluesman.

“It’s no fun to just do what everybody expects you to do,” he says, then leans forward with a grin. “I’m gonna shake it up on you: Surprise, motherfuckers!”

A classic example of a gifted guitarist stretching aggressively past the old ways was the late Jeff Beck, who died in 2023. Gary Clark joined Clapton, Rod Stewart, Billy Gibbons, and an all-star cast of rockers that May for a tribute to Beck at the Royal Albert Hall in London. Clark chose to play “Cause We’ve Ended as Lovers” from Beck’s 1975 instrumental album, Blow by Blow, an early peak in Beck’s solo career.

“I like people who take risks,” he says, “who [take] what you think is a basic ingredient and flip it on you and give you something gourmet and unexpected.”

Stevie Wonder collaborated with Gary for “What About the Children,” as a result of a video Clark posted in the early days of COVID and at the height of Black Lives Matter protests.

“I was just fed up— a little anger, a little frustration, a little bitterness. It was COVID. Everything was shut down. The news was all on our phone, and we were just living through the phone. So I posted this video, going on this long rant about what’s going on with people shooting people, racism, and haves and have-nots. And Stevie hit me up and he said, ‘I understood what you were saying in your video. I have a song for you.’”

Wonder sent him a demo of himself playing harmonium and singing into his phone. Clark could hear a dog barking in the background and Wonder singing unfinished lines, including, “‘What about the children playing in the street?”

The song’s structure and arrangement were right there, so Gary told Wonder, “I’ll get together with my band. This is perfect.” With the track worked out, he and Sciba translated Wonder’s unfinished lyrics and mumbled words into a complete song. They sent it back to Stevie and asked if he would sing on the track. Wonder then invited them to his studio in Los Angeles. Sciba especially wanted to hear Wonder back on the clavinet, the funky keyboard at the heart of classics like “Superstition” and “Higher Ground.”

During their two days together, Stevie played harmonica and sang, trying out different vocal ideas, pushing himself. He meticulously went over every detail of the track. “I was like, ‘Oh, this guy does not play it safe,’” Gary recounts. “He’s relentless and he’s super humble about it, going, ‘What do you think?’ Me and Jacob are in the studio control room, jaws on the floor, just going, ‘Yeah, yeah, you got it.’ He goes, ‘No, I need genuine feedback, guys. We are making this together. I don’t need you to just yes me. Let’s collaborate.’”

On the same trip to L.A., Gary and Sciba worked on “Funk Witch U” with George Clinton at Henson Studios. “He lights up a big old spliff, passes it around, we get to laughing, get to gigglin’,” says Clark. “He goes in there and lays that shit down in maybe two takes. And he’s just having fun with it the whole time. He’s dancing, we’re dancing, and he was quick in and out, just like that.”

Midway into the album are two romantic songs of very different moods, beginning with the old-timey jazz guitar of “To the End Of the Earth,” played and sung by Clark alone. It tells a story of idealized romance, partly inspired by a self-titled 1963 album of jazz ballads by John Coltrane and Johnny Hartman. On the track Gary sings: “You’ll never be alone/We’ll forever be in love/Just tell me, darling, will you be mine?”

“I wanted you to think of love as it was portrayed in the ‘30s and ‘40s in film—beautifully lit, kissing under an umbrella, Clark Gable saying something slick,” he explains.

The next track is another kind of romantic message, slipping into a classic soul groove in the Al Green tradition, meant as dramatic contrast to the song before, a bleak reading of the next chapter in the same love life.

“It’s the honeymoon phase versus the, ‘Oh shit, we’re in this for over a decade, plus some. We’re doing this for real. Shit’s going crazy. You’re over here. I’m over there. The kids are going nuts,’” he says. “Al Green is getting the hot pot of grits thrown on him. It’s a love song. It’s the same woman. But what the fuck happened?”

He sometimes asks that question about the town he grew up in. Austin has seen major changes during his lifetime. The scene that launched him from “the Live Music Capital of the World” is not what he remembers. Clubs have faded away. Development has changed the cityscape. His hometown is busier, and the music scene has seen famous stages where he once learned to play the blues disappear.

“I was saying something [about it] to my dad. He said, ‘Shut the fuck up. I’ve been here since I was a kid, and my folks have been here since they were kids. So you’re complaining about what’s happened in the last 20 years? I’ve seen this whole thing change. Change is happening. Either you’re in for the ride or you’re gonna get kicked off and you just get to watch.’”

There’s less “turquoise and cowboy boots” around now, Gary notes. “At some point I’m going to slow down and do my part and get involved again,” he says.

On the album, Gary again has the backing vocals of his three sisters, Shanan, Shawn, and Savannah. “It kind of completes the band on many levels,” says Sciba of their sessions. “Anytime you can get siblings to sing together, they just blend different. They finish each other’s phrasing. It’s amazing. When they’re in the studio, Gary is not the boss. He’s the middle brother. The family dynamic becomes very obvious.”

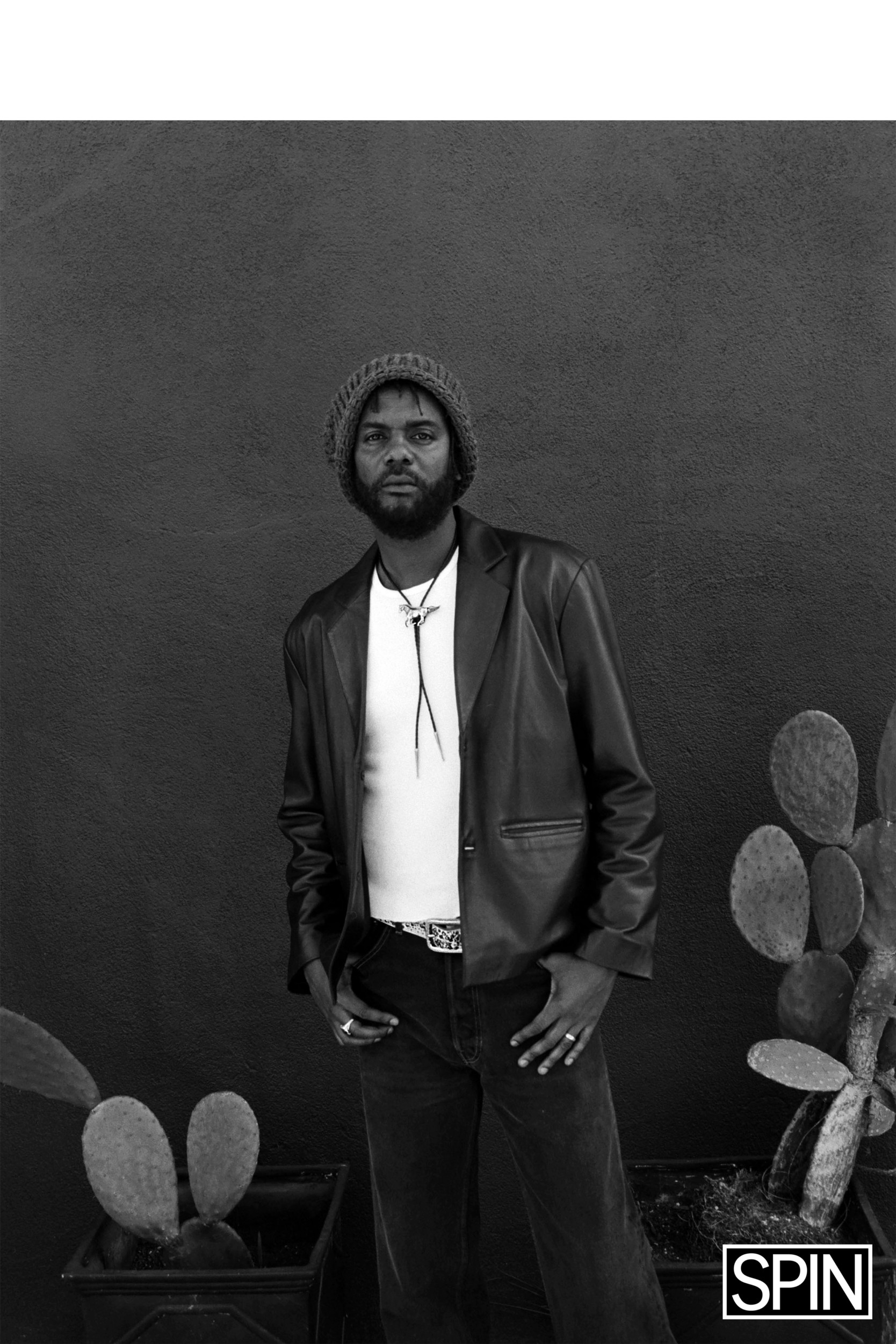

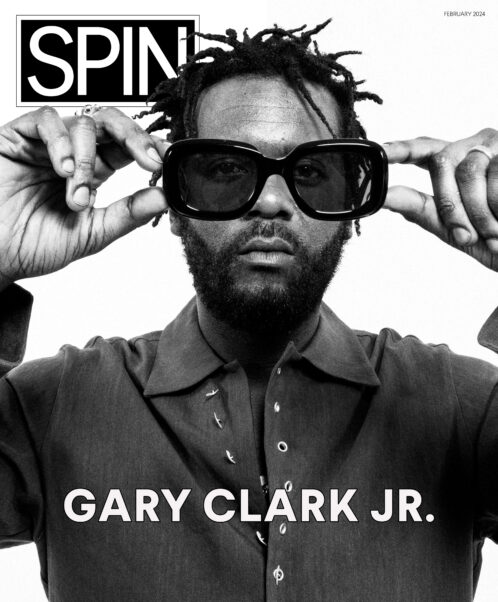

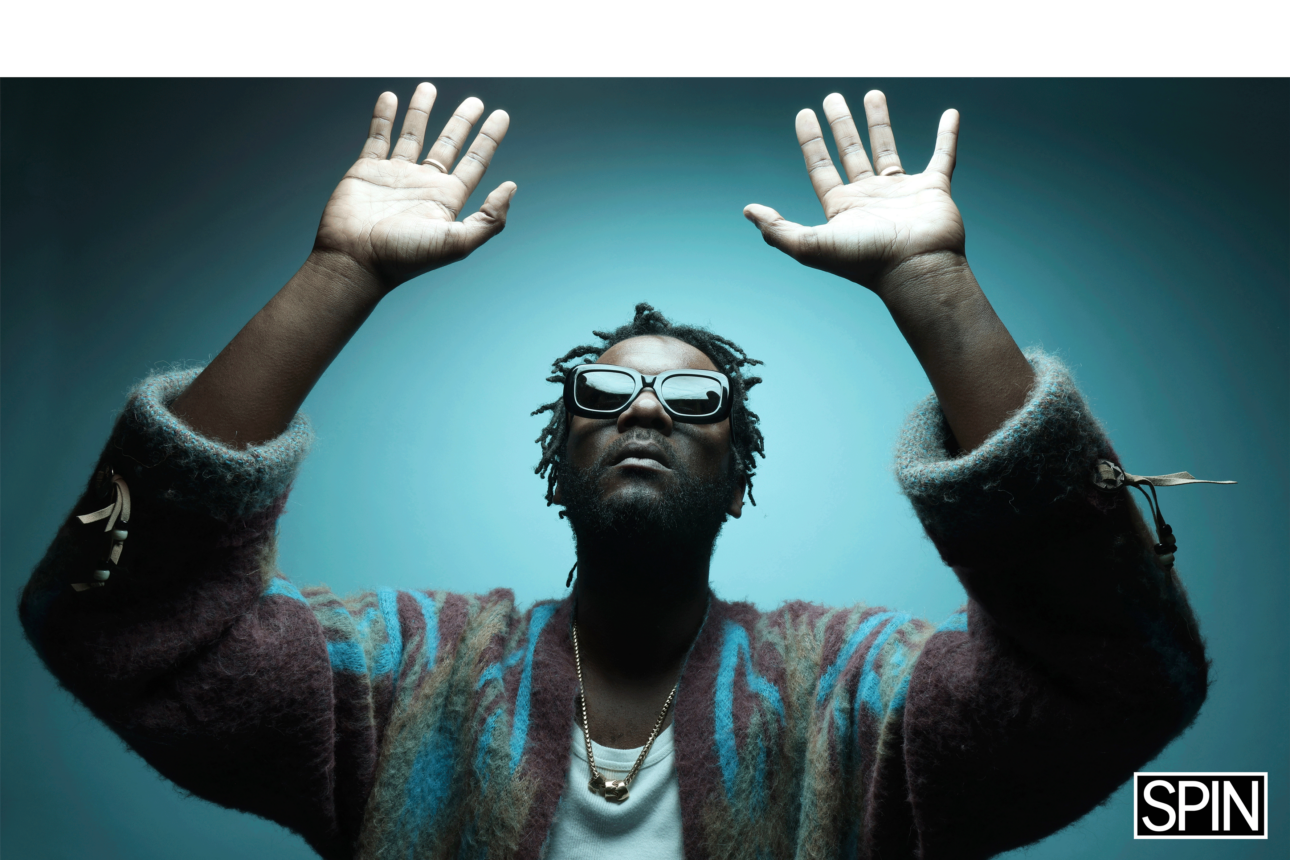

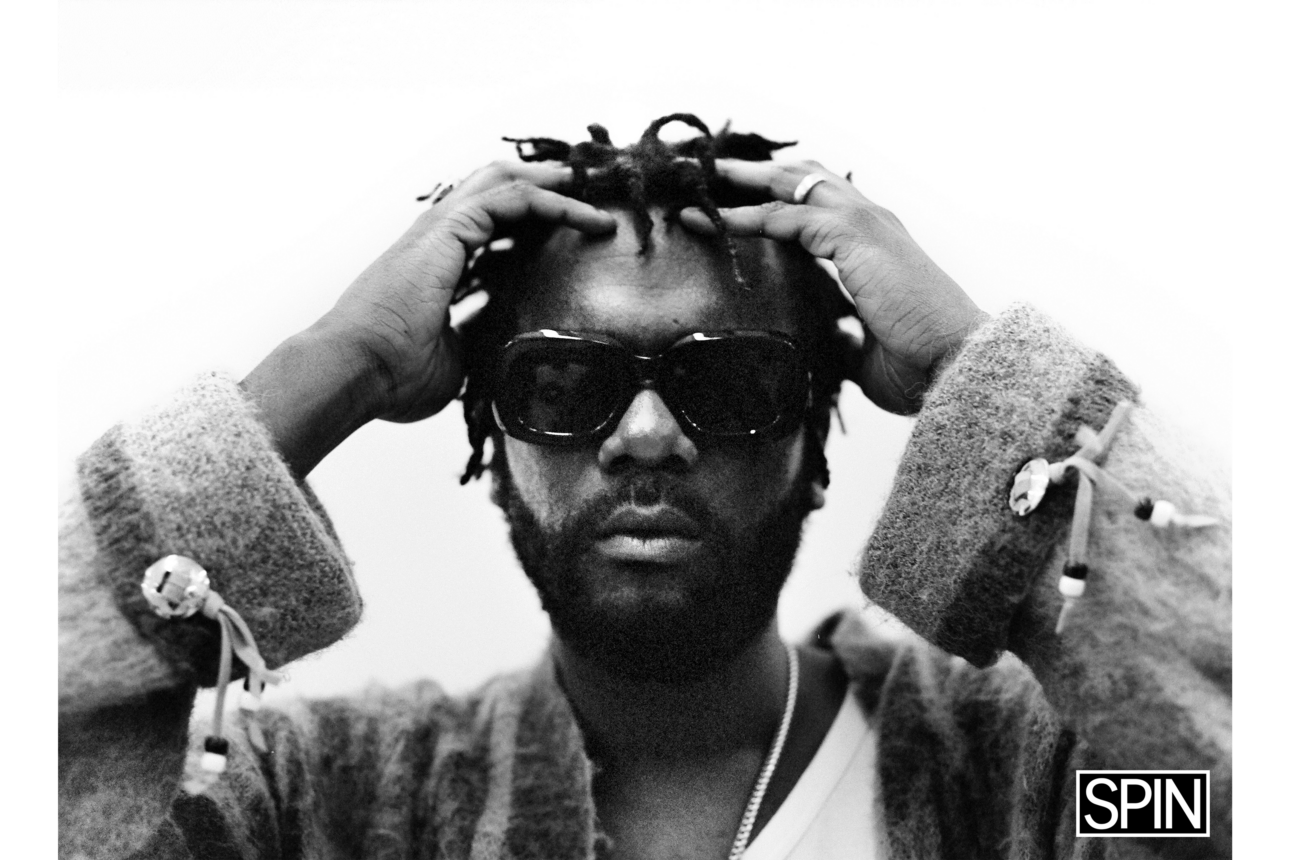

Photo Credit: Mike Miller

Photo Credit: Mike Miller

Photo Credit: Mike Miller

Photo Credit: Mike Miller

Photo Credit: Mike Miller

Photo Credit: Mike Miller

Photo Credit: Mike Miller

Photo Credit: Mike Miller

Photo Credit: Mike Miller

Photo Credit: Mike Miller