The Libertines have inadvertently tapped into the human quest for immortality, which comes with living on the edge. Since they formed in 1997, the London four-piece has been as synonymous with their music as they have tabloid drama, particularly Pete Doherty, his antics and addiction, and subsequent foibles and fallouts. Doherty’s counterpart and co-frontman, Carl Barât, has been open about his own personal challenges. But what you see of them—be it on stage or in interviews or in social settings, their relationships, the music, and the band—no one can accuse the Libertines of not being exactly who they are.

But now there’s a long-awaited new record to focus on. All Quiet on the Eastern Esplanade is the Libertines’ fourth album in 22 years. It comes almost a decade after their last album, Anthems for Doomed Youth, and it’s the first Libertines album created with a clean and sober Doherty. The group’s four members, rounded out by bassist John Hassall and drummer Gary Powell, are settled as family men in four different parts of the world.

“The energy is the purest it’s been in years,” Barât tells me, referring specifically to Doherty. “Making new music has brought us closer together again. Having a shared perspective unencumbered by drug habits is a blessing. We have both moved on a lot since the early days—age plays a part in this, but also the perspective of what’s important and how little time we have on this planet. We have learnt to better tolerate each other’s foibles and see the good things.”

Doherty has been free of hard drugs—that is, crack and heroin—since December 2019. His wife, Katia de Vidas, captured 10 years of his drug use, from 2006 onward, in over 200 hours of video footage, which was released last year as the no-holds-barred documentary Pete Doherty: Stranger in My Own Skin.

“It wasn’t easy to watch,” Doherty told Brut of the film. “Because I got clean, I think it made sense for Katia to make a film about addiction: survival, I suppose; kind of redemption…but that wasn’t on the cards really. I never thought I would get clean, to be honest. Heroin was one of the gang as well. It was always there. I felt like I had a balanced relationship with it. I didn’t realize at the time that I could just shut the door to it. I thought it would always find a way back in.”

These days, Doherty’s indulgences of choice are cheese and sugar, surely plentiful in Northern France, where Doherty lives with de Vidas and their almost one-year-old daughter, Billie-May. She is the third of Doherty’s children, who also include a 20-year-old son and a 12-year-old daughter from previous relationships.

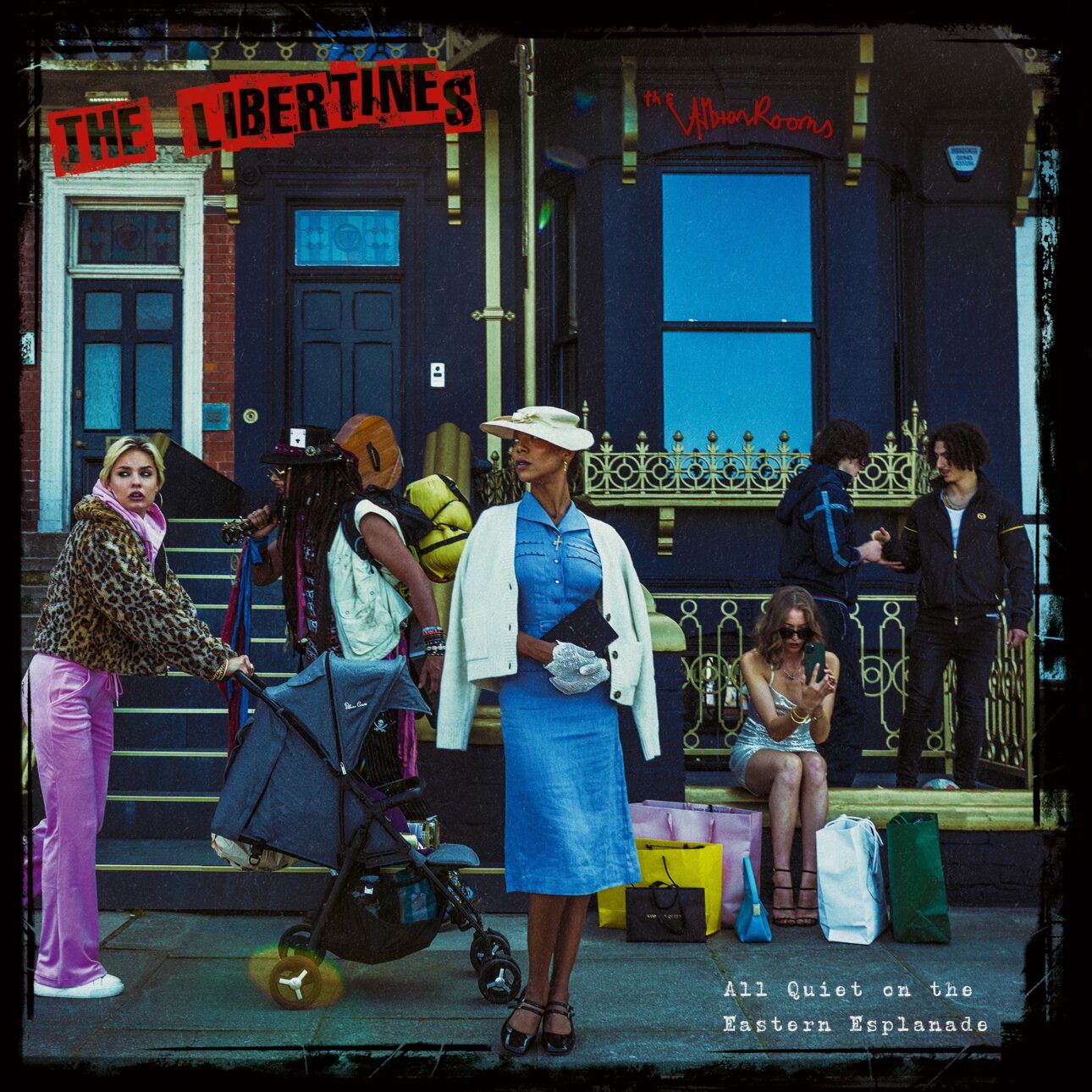

The Albion Rooms is a jointly-owned piece of Libertines’ real estate, which serves as a boutique hotel with two bars (neither Doherty nor Barât have sworn off alcohol), as well as a recording studio and a venue, located in the coastal British town of Margate, where Barât makes his home with his family, which includes two sons, aged 13 and nine.

Barât looks much as he always has, whippet-thin with floppy rock star hair, and a butter-wouldn’t-melt set to his jaw. He’s always come across as the person holding everything together in the Libertines, with or without Doherty. The two of them performing, spitting into the same microphone, is an unmatched rock ‘n roll force. When Barât had to go it alone because of Doherty’s indisposition, his commitment was almost greater, and he leaves it all on the stage.

“Like any relationship, the chemistry is the nucleus,” says Barât. “If it’s still there after many years, it will inevitably be stronger. You can only get blindsided by certain types of problems for so long before you learn what’s important, although that can take many years as well. I never know what tomorrow brings, though. We have shared a lot of life.

“Becoming a father made me decide to stop putting my life on the line,” he continues. “I’ve been in therapy for a decade. I have more coping/managing strategies. It helps me to relate better to other people too.”

The Libertines are relating the best they ever have, hence the Albion Rooms joint venture. “We built [The Albion Rooms] to make this record. It took years, and in doing so, the album, its meaning, and purpose grew around us, so there was no other place we could have made it,” says Barât.

“Having The Albion Rooms has stirred the loins of creativity between us and reinvigorated that old bond that we used to have together,” says Powell.

All Quiet On The Eastern Esplanade (so named because of The Albion Rooms’ location) was recorded over a period of four weeks with producer Dimitri Tikovoï (The Horrors, Charli XCX, Becky Hill), who is known for his pop polish. This is the next step along from Anthems for Doomed Youth, which was helmed by another pop producer, Jake Gosling. These later albums are an evolution from the garage rock-meets-post punk immediacy of the Mick Jones-produced Up the Bracket and The Libertines from two decades ago.

For All Quiet On The Eastern Esplanade, Tikovoï worked the Libertines hard, with daily 12-hour, alcohol-free sessions. This method worked well, according to Hassall, who says, “We just got in that really creative bubble, where everyone was doing different stuff, really working to their strengths, and not holding back—definitely the most enjoyable album process that we’ve ever had.”

“It had to be this way,” says Barât, who had previously done some writing with Tikovoï. “He is accomplished and trusted. I knew he was great at working with potentially difficult artists, and he works from the songs outward, not the other way around. We worked right up to the wire on the final day and nearly didn’t finish ‘Shiver.’”“It went great, purely on the basis of our rekindled relationship,” Powell says. “The relationship was good beforehand, but now it has been kind of galvanized to a point where anybody can say anything to each other, and even John is coming up with song ideas, whereas our job was always basically just to back up Peter and Carl, and fill in the gaps.”

All Quiet on the Eastern Esplanade was finished in one week at La Ferme de Gestein Studios in Normandy, with additional production and mixing by Dan Grech-Marguerat (Lana Del Rey, Liam Gallagher, Paul McCartney). “We went to Normandy when the cabin fever took hold because we had to,” says Barât of the location change. “It gave us great perspective on things.”

Prior to beginning recording at The Albion Rooms, Barât and Doherty decamped to GeeJam Studios in Jamaica for writing sessions. They had a disparate mix of experiences there, including watching Queen Elizabeth’s funeral on television. “It felt surreal, as Jamaica is an ex-outpost of her inherited empire. It felt like a turning point in our world,” says Barât, and they got a standout song out of it: “Shiver.”

They also found themselves in a local church “in a shack on a hill,” says Barât. “It was a powerful experience seeing people so intoxicated in spirituality. The drummer was insane. It’s where all the drummers cut their teeth on the island apparently. That and a screaming preacher was quite a combo. There was a girl there, Sister Mary, [who] looked both lost and found. She made it onto our record on ‘Mustang.’”

All Quiet On The Eastern Esplanade has the vim and vigor of classic Libertines songs, as well as the razor-sharp and relatable lyricism on tracks like “Run Run Run” and “Oh Sh*t.” There is also the signature Libertines cast of fictitious characters in real situations on songs like “Baron’s Claw” and the Swan Lake-inspired “Night of the Hunter.” Atypical for the Libertines are songs such as “Merry Old England,” with orchestral elements and topical commentary on current events.

“We once sung of imaginary worlds steeped in history and make-believe, and I suppose we still do,” says Barât. “We all inherit the earth in some way or another as we grow up. Singing about the world around us has become important somehow. It’s good to be in the room once in a while.

“I can only write between episodes personally,” he continues. “The mental health issues and addiction, we can sometimes manage, but not without occasional Herculean and sometimes Sisyphean challenges. I’m just enjoying some calm whilst I can. I’d love to think it will be wine and roses from here on in. Maybe it will be, eh? Let’s say that’s the case, we still have a good few lifetimes’ worth of material to draw upon, so I can’t see it getting boring.”