Eccentrics, rejoice—Sleepytime Gorilla Museum’s doors are open to the public once again! With their new album, of the Last Human Being, the recently reactivated band returns to the road and to the maximalist, forward-thinking rock music that made them cult heroes in the 2000s.

This is music that defies easy categorization. Songs frequently collapse into themselves only to rematerialize in thrilling new shapes. Players slide effortlessly from instrument to instrument, both conventional (guitar, violin) and invented (pedal-action wiggler, electric pancreas—electric pancreas?). Oblique ideas and recurring characters cycle through the reference-heavy lyrics, and collaborators make chance appearances onstage whenever they’re available.

There’s a teetering, shambolic quality to the whole affair, but that’s a carefully deployed effect that can only be achieved by being totally locked in—which Sleepytime most certainly are. To prepare for their upcoming tour, their first since 2011, the band put in two weeks of 13-hour rehearsal days. “We averaged getting through three songs a day,” says violinist and vocalist Carla Kihlstedt.

Entering Sleepytime Gorilla Museum’s orbit can feel a bit like climbing inside a Sleepytime Gorilla Museum song. We met up on their tour bus, an old green Greyhound that’s been customized by the band’s bassist and resident mad scientist, Dan Rathbun. (Rathbun had to miss our interview, but I could see his Jarmuschian coif of white hair bobbing up and down as he paced around on the phone, frantically trying to secure a replacement part for the bus.) Over the course of our conversation, a revolving cast of supporting characters—dancers, academics, the members’ own children—clambered onto the bus to weigh in on a question or two before vanishing. The band drank tea and ate chili, prepared in an onboard kitchen, and they frequently finished each other’s sentences, or laughed over anticipated punchlines. It was exhilarating and occasionally overwhelming.

Their set that night, at Cleveland’s Beachland Ballroom, would be much the same.

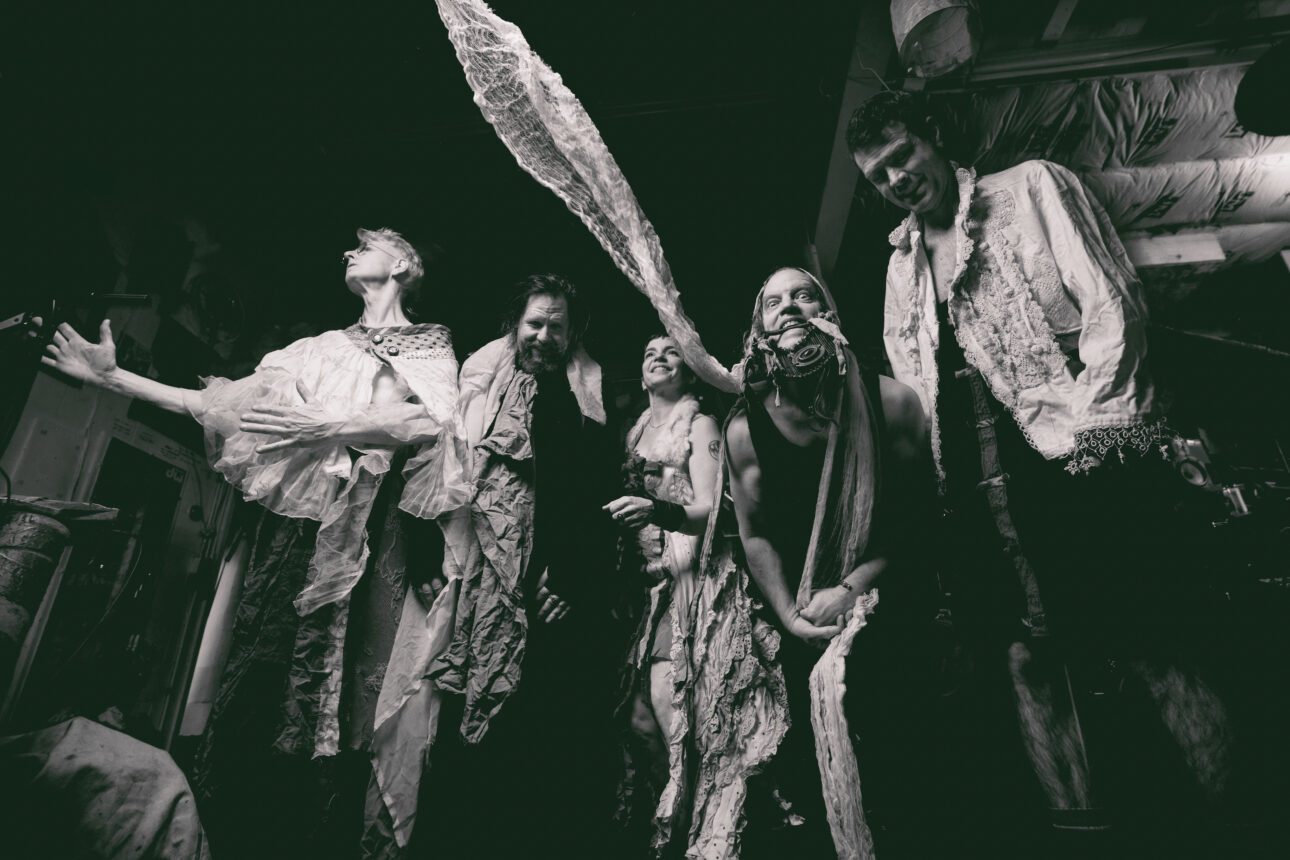

“There’s always the urge not to just have a rock show with this band,” says drummer Matthias Bossi. “There’s a fair amount of weird little interstitial noises and monologues and characters, and bits of theater, that push it past just playing the songs. That’s always the goal in an evening with the Sleepytime Gorilla Museum.”

It’s a goal that’s remained intact since the band’s earliest days. Sleepytime Gorilla Museum began operations in 1999, with a membership pulled from existing Bay Area groups like Idiot Flesh and Charming Hostess. The band arrived with a dense encyclopedia of lore and a pronounced Dadaist streak. Their first show, infamously if not verifiably, was played to a single banana slug. On their records, Sleepytime unleashed a sound they called “rock against rock,” a frayed amalgam of prog, metal, jazz, avant-garde classical, and 20th century chamber music.

But to really understand what Sleepytime was doing, you had to dig deeper than the music itself.

“All those [extratextual] elements, which have been in place from the beginning, I feel like they have a big effect on the overall mood of what we’re putting out,” explains vocalist and guitarist Nils Frykdahl. “To whatever extent people delve in, they feel like they’re getting a little piece of something bigger.”

“You can’t just transcribe Sleepytime music into pure sine waves and have it be the same thing,” adds guitarist and percussionist Michael Mellender. “The textures are a huge part of it.”

Across three acclaimed albums—2001’s Grand Opening and Closing, 2004’s Of Natural History, and 2007’s In Glorious Times—Sleepytime built out a madcap, post-apocalyptic universe with real political heft. Frykdahl credits Samuel Beckett as the predominant influence on the question at the center of the band: “The world has ended—and then what happens?” That question serves as the basis for both absurdist comedy and serious philosophical inquiry, though the line between the two is never totally fixed in place.

“I think there’s some kind of natural balance,” Kihlstedt says. “We’re on a seesaw, and there is some kind of natural balance between them, which sometimes implies a momentary imbalance.”

“The music has a way of helping balance us,” Bossi adds. “There are some lovely, pastoral passages that allow the night to breathe. But then, I think when it comes to relating to the audience outside of the music, it is a cage match. There are no rules. There’s a lot of absurdity flying around, and really, no one in the band has ever told another person, ‘You shouldn’t do that to the audience.’ It varies night to night. Sometimes it can be very warm and conversational, and other nights…”

“It’s very austere and surreal and absurdist,” Carla says, finishing her partner’s thought.

“It’s either Sesame Street or Klaus Nomi,” laughs Bossi.

Of the Last Human Being pushes Sleepytime’s mingling of humor and heaviness to new extremes. The album had its origins as a theater piece—a comedy, according to Frykdahl, about “the precarious place of the human being.” Riffing on the post-apocalyptic idea at the core of the Sleepytime mythos, the band tried to channel the way San Francisco high society looked at Ishi, the early 20th century performer and so-called “Last Wild Indian.”

“He had this fascinating little run that only lasted a few years, unfortunately, as a living museum exhibit in San Francisco,” Frykdahl says. “People would come and see him flake arrowheads from obsidian and start friction fires. Society people would show up with their Merry Widow hats and go, ‘Oh, look!’

“The general consciousness of the American public is such a potentially feeble thing,” he continues. “The one we have right now is so divisive, and so influenced by the merest shred of provocation. People just say, ‘Oh, that’s how it is!’ That mindset at the time [of Ishi] took a big turn toward this collective lament. They were like, ‘Wait a minute, maybe there was something valuable there. And that’s the last guy. Oh, well, maybe we should make a statue.’ So The Last Human Being story was sort of a transplanting of that.”

Sleepytime began working on the album and its accompanying short film in 2010, but circumstances pulled the band apart before they could finish. Kihlstedt and Bossi moved to the East Coast to start a family, and the band announced a run of farewell shows, “to give it dignity rather than become a Sleepytime cover band,” per Frykdahl.

Internally, though, the band believed they were just taking a break.

“There was never any talk of a breakup or a split-up or anything like that,” Mellender says. “We had every intention of getting back together and finishing this record that is now out. Finishing the movie that is soon to be out. All these things were left up in the air, and it was just a matter of the insane logistics of getting back together, which just happened to have taken 13 years.”

Last year, the wheels finally started turning again. Sleepytime launched a Kickstarter campaign to help get the album and film across the finish line, and they started figuring out how they could exist as a bicoastal band. Songs were completed remotely, a first in Sleepytime history, and a new record deal was signed with the emergent Avant Night Records. A plan to return to the live stage was hatched. Carla Kihlstedt had to rehab two frozen shoulders—a debilitating condition for anyone, but perhaps especially for a violinist—and as she recovered, the reality of a new, improved Sleepytime Gorilla Museum came into focus. The music still churns with feverish intensity, but the band has become smarter about how they achieve that effect.

“My whole way of playing, physically, and my understanding of breath and movement, I feel way more like there’s many places in the set where I’m able to regenerate my energy,” Carla says. “So I get off the stage having been full-on physically, and I still feel like, ‘Great! Where’s the next set?’ Which is really new for me. I used to get off the stage fully winded and totally exhausted.”

Some band comebacks feel obligatory, or financially motivated. Sleepytime’s has felt genuinely reinvigorating. There’s a palpable energy among the members when they talk about the songs they’ve almost nailed in rehearsals, or the possibility of recording future Sleepytime music remotely. The shows themselves have been triumphant, with fans who thought they would never get to see this band, who meant so much to them, finally witnessing them in the flesh.

In Cleveland, the room was abuzz all night. When Frykdahl came out in his kabuki-style makeup and handmade costume, a guy behind me yelled, “Oh, my God, it’s Nils!” The mosh pit, populated by teenagers and old heads alike, was the most joyous one I’ve seen in ages.

“There’s an incredible warmth coming from the audience on this run,” Carla says. “It really kind of bowls me over sometimes. The thing that has been most rewarding is when a whole band of people will come straight from band practice to the show, and it’s like five young kids. Someone said in Chicago, ‘You guys are our KISS.’ [Laughs.] I’m not quite sure how I feel about that, aesthetically.”

I suggest that the comparison begins and ends with the use of stage makeup.

“Let’s hope,” Frykdahl replies. “Worst band of all time.”

Carla quickly rights the ship: “The more exciting thing is when they say, ‘You’ve given us permission to go deeper into what we’re trying to do.’”