“Oh! Yeah! A picture here!” says Alice Randall, sitting in the office of her apartment in the west end of Nashville.

She gets up from her desk and grabs a blown-up, black-and-white photo that’s propped by the window behind her, then holds it up to the computer camera. It’s of a family, dressed up, sitting at a table in a fancy nightclub. She points to a child on the right of the photo. “That,” she says, “is Little Girl Me.”

She points to the others: her father George in a suit, her mother Mari-Alice in a nice dress, a young woman—her babysitter Beverly, who, she explains, went on later to become a judge. “This is the day, ringside,”—her father’s term for it, she says—“when the Supremes opened at the Copacabana and sang the country song ‘Queen of the House.’”

Her parents look serious, the babysitter happy. But what stands out is Little Girl Alice, her eyes looking off to the side with a bright sparkle and a grin like she’s about to burst from joy. Talking about it today, 50 years later, she still looks just as excited. “I was really there!” she says.

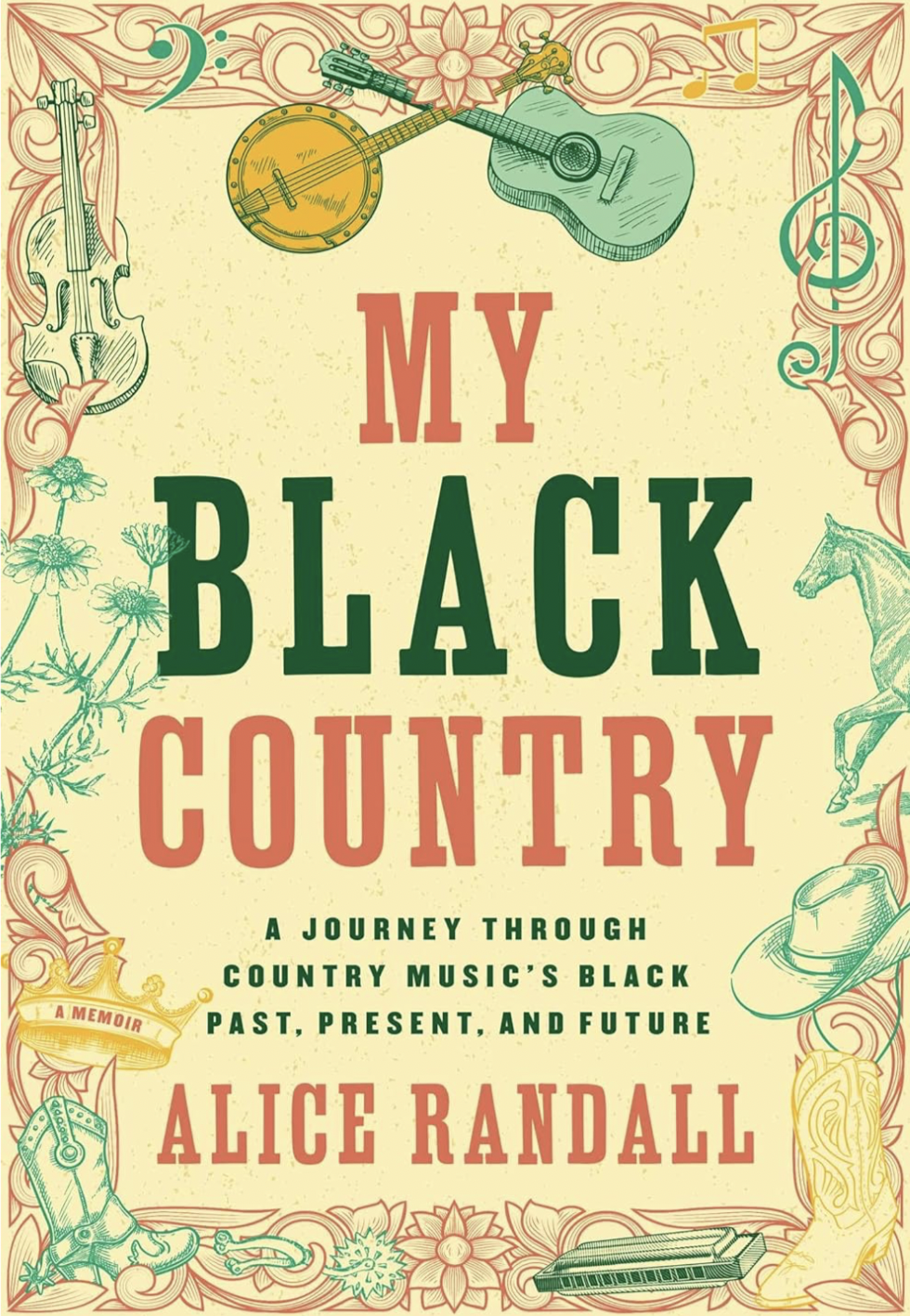

It’s a key episode early in her new book, My Black Country: A Journey Through Country Music’s Black Past, Present, and Future. The book, as the title suggests, traces a cultural history—one that is a hot topic right now. But at the same time, it’s a very personal story, one of her life and her connection to that history. And that photo shows a crucial moment, a turning point.

She was six, and her family had traveled from Detroit, where she was born and raised, to see this performance in New York. The hometown Motown trio was debuting at the glamorous Manhattan club with a show designed to break them well beyond the soul market, and her father, who was friends with Motown founder Berry Gordy’s sister Anna, wanted them all to be there to see it.

But the song Randall mentions, Jody Miller’s winking “answer” to Roger Miller’s (no relation) “King of the Road,” was another kind of breakthrough for her. This would be the first time Randall ever saw Black artists do a country song. And Black women artists at that.

A companion album to the book, also titled My Black Country, is filled with Black women singing country songs: Allison Russell, Rhiannon Giddens, Leyla McCalla, Rissi Palmer, the duo SistaStrings, Adia Victoria, Sunny War, Saaneah Jamison, Valerie June, Miko Marks, and Caroline Randall Williams, each bringing a distinctive voice and artistry to the project. (The album is released on Oh Boy! Records, the label founded by John Prine.)

The thing is, every one of the songs was written or co-written by Randall. They come from her 41 years in Nashville as a respected songwriter, as well as a best-selling author, noted academic, cultural historian, and activist. And the album, too, tells both the cultural and personal stories of the book.

It starts with “Small Towns (Are Smaller for Girls),” originally done in 1987 by Holly Dunn, but here sung by Leyla McCalla. And it ends with “XXX’s and OOO’s (An American Girl),” which when done by Trisha Yearwood in 1994 made Randall the first Black woman songwriter to have a No. 1 country hit.

The latter, though, is radically reworked and performed by poet-activist Caroline Randall Williams—Randall’s daughter. While the Yearwood version has the singer dreaming of breaking out of a simple life, the new one has Williams steely, defiant, owning the “ribbons and bows” in her hair almost as scars of the battles she’s fought. The final words she speaks in the song are of hard-earned pride and progress:

“Still getting better now for American girls.”

It’s in honor of Little Girl Alice. And a lot of girls.

“There is a narrative here, and there is a definite order—a lot of thought and intention went into that,” Randall says of the album.

It unfolds through tales of a woman bandit showing up her dismissive male companion (“Girls Ride Horses Too,” a 1987 hit for Judy Rodman, sung here by SistaStrings), through several songs written for an unproduced movie project she conceived involving the stories of Black singing cowboys such as Herb Jeffries and Nat Love. (The story of her getting into Quincy Jones’ house, uninvited, to pitch the project—successfully—is a book highlight.)

And while none are as drastically reworked as “XXX’s and OOO’s,” all take on new aspects, new depths, in these performances. Most dramatic might be Giddens’ version of “The Ballad of Sally Anne,” a song about a lynching. In its first recording by fiddler Mark O’Connor with vocalist John Cowan, it’s a tragic story of a horrifying injustice. Giddens makes it something more, with her banjo (yes, the one you’ve heard on Beyoncé’s “Texas Hold ‘Em”) and voice bringing out the deepest darkness of the traditional-sounding melody, the mood then exploding with horns brought in by album producer Ebonie Smith—a motif that is used through the album.

“When Rhiannon sings that same song it embodies resistance,” Randall says. “And when Ebonie put those horns on that song it was, why?—because it reminds you that lynchings happened into the middle of the 20th century. Lynchings aren’t something that just happened in the Nadir in 1880 and 1890 and 1910, when you would use that old-timey sound, which is what was on the original version. Emmett Till was lynched and dragged down that road. Lynching happened in American into the ‘40s, and there’s some debate that it happened into the ‘50s, into the birth of rock ’n’ roll. That’s what the horns are telling you.”

That her daughter, her next generation, is there at the end is the flowering of seeds Randall—and so many others—have sewn.

“Caroline wrote her deconstruction/reconstruction independently,” she says. “And I loved that they sampled DeFord Bailey on it. That was the only thing I requested.”

Bailey, grandson of former slaves, was the first-ever performer when the Grand Ole Opry started airing on WSM radio, his harmonica rendering of the sound of a train the first sounds for that now-venerable broadcast institution.

“According to me,” she wrote in the book, “Black country was born December 10, 1927, when DeFord Bailey played ‘Pan American Blues’ on Barn Dance, a Nashville radio show blasted out on the WSM airwaves.”

To Randall, Bailey is a hero who has not gotten his due, and she wants to change that. Same for Lil Hardin, who was not only the piano player in Louis Armstrong’s 1920s groups, writing many of the ensemble’s key songs (and then married to Armstrong and helping direct his career), she also played piano on Jimmie Rodgers’ 1930 recording of “Blue Yodel No. 9,” one of the spark-points of country music—and, Randall believes, likely brought the song to his session.

Bailey and Hardin are forces to which she refers throughout the book, foremost for her among many who made their marks but have been pushed to the side in history. They are present with her through her own stories of childhood, family dramas, adventures in Nashville and Hollywood, and her own transition from difficult daughterhood to enriching motherhood.

“They were my spirit guides in some ways,” she says of Hardin and DeFord. “I thought of myself as chasing Lil Hardin. Also I feel that she and DeFord needed to get in the public [eye]. I think I’m the first person to ever document his work in writing a political jingle and helping get the first Black state senator elected in Tennessee. People want to tell this horrible story, television shows still referencing that he died a shoeshine boy. First of all, in that period that he was a shoeshine person, it was much more akin to owning a beauty shop. So I wanted to complete his story, and I really wanted to tell Lil’s story.”

Randall notes that Ray Charles’ No. 1 hit version of Hardin’s “Just for a Thrill” came out in 1959, the year she was born—several years before he broke barriers with his Modern Sounds in Country and Western Music album. It was deep in her consciousness before she was even five, by which time she had written her own first country song, singing to herself “Daddy, don’t go in that B-A-R” while sitting in her father’s car. In 2000, while grappling with difficult feelings about her dying mother, she retraced a rail journey Hardin had once made.

“I wanted to honor her,” Randall says. “That whole trip, part of it was chasing the ghost of Lil from Chicago to San Francisco.”

And she says this from her home, across the street as it happens from the mansion built by the Robinson family, which owned WSM, on riches made from the broadcast series Bailey kicked off, and down the street from a house of a family for which Bailey had worked as a valet when he first came to Nashville.

So yes, those two being written out of the story of country music’s start is personal to Randall, an energy that drives her through her exploration of her own story. And it’s not a typical Nashville songwriter story, well beyond her being Black.

There’s a 1993 movie, The Thing Called Love, with Samantha Mathis as a young woman fresh in town heading to the Bluebird Café, the Nashville proving ground for singers and songwriters. Randall wrote a few songs for the movie. And she knew the story, as she, like so many others, also went to the Bluebird on her second night there. But few right away get Steve Earle’s attention with him becoming mentor and advisor, as happened on that very evening.

And not many came there from Harvard, as Randall did, arriving with a cum laude degree in English and American literature. And even fewer went on to write novels standing at the forefront of modern Black fiction—starting with 2001’s headline-grabbing The Wind Done Gone, a parody of Gone With the Wind told from a slave’s perspective. And only a very select number went on to become professor of African American and Diaspora Studies and writer-in-residence at Vanderbilt University, not to mention holding the school’s Andrew W. Mellon Chair of the Humanities position. That number is an emphatic one, Randall alone.

(She’s also the only one, certainly, to have found herself trying to force a chicken into a Nudie style suit for a Johnny Cash video shoot—with assistance from Roy and Barbara Orbison. But you have to read the book to get that whole story.)

Naturally, she’s watching the Beyoncé-boosted conversation about Black country that’s raging these days with great interest—and, of course, she had no idea when she started working on the book that this would be going on now. But it’s a conversation she’s been leading for decades, in her work as a songwriter and an academic. One of the first classes she introduced at Vanderbilt was on country lyrics in American culture, and since 2015 she’s taught a course in Black country. And her 2006 book, My Country Roots, features prominently contributions from Black artists and writers in its comprehensive look at country music.

She takes pride in seeing the emergence of a younger generation of Black country-rooted artists represented by the women singing her songs on the My Black Country album, each a distinctive presence established solidly well before Beyoncé took up the call. And the push-back against Beyoncé is, of course, nothing new to her.

“I think the people listening to ‘XXX’s and OOO’s’ for 30 years, the audience doesn’t know that a Black woman wrote that necessarily at all,” she says. “In Nashville, the co-writers, the record labels, all of those people knew. I’ve had writers who would not write with me because I was Black or who did not want me in the industry. One of the people [who], when I arrived in town I thought was one of the great poets of the genre, stepped back four feet from me and said, ‘I’ve been at this too long if I have to compete for cuts with [N-word] girls from Harvard.’ And I just said to him, ‘I am. And you do.’”

She laughs about that now.

“I was surprised by that one,” she says. “I was more surprised once when I was writing with someone I liked and I pushed back on a line we were editing and they literally, before they or I knew it, said, ‘Don’t go acting like an uppity N-…’ They stopped themselves halfway through the phrase. Uppity.”

An ingrained reflex?

“Ingrained powerflex,” she says. “I never wrote with them again. And their biggest song was the song they wrote with me.”

But she’s also had a lot of positive, supportive experiences. One revolved around her song “Who’s Minding the Garden?”, a song about environmental crises that she updated to cover current climate concerns for the new version done on the new album by Rissi Palmer. The first released version was by Glen Campbell in the early 1990s. Campbell was drawn to the message, comparing it to his Jimmy Webb-written hit “Galveston,” which took an anti-war stance in the Vietnam era. When she went to the studio to meet Campbell, she had Caroline, then just four or so, in tow because she’d fallen at camp and scraped up her face.

“I asked Glen’s people if I could bring her to the studio with me,” she remembers, fondly. “And he was so wonderful to her. He got on his knees and told her how pretty she was. And he was a beautiful man, basically like an angel. And then he stood up and told me, ‘This song is so important.’ And he said, ‘It’s ‘Galveston’ good.’ And that was just wonderful.”

Back to Little Girl Alice, her grown-up self wants to point out something specific in that photo.

“That little dress I’m wearing,” she says. “It’s scalloped. It’s so exquisite. My Aunt Mary Frances literally sewed for Hollywood and sewed for couture in New York. This was an exquisitely crafted, amazing dress, professionally designed and done.”

Another Black artist who influenced her, whom Randall wants to make sure gets her due.