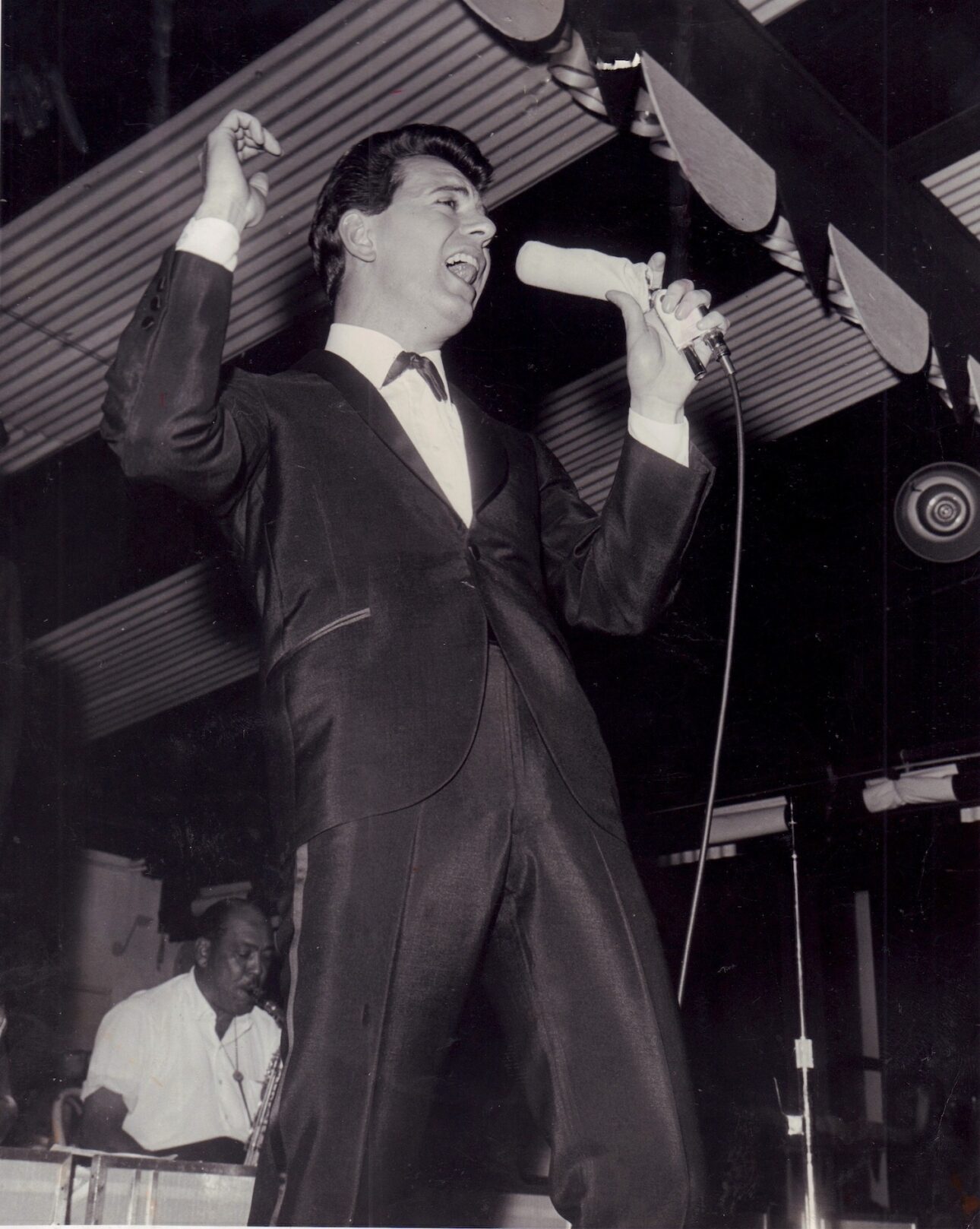

As the Dion of Dion and the Belmonts, he was the first mononymous rock star. He gave his airplane seat to Ritchie Valens and thus became the sole survivor of the ill-fated Winter Dance Party tour. He’s on the cover of Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band and was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in the same year as the Rolling Stones.

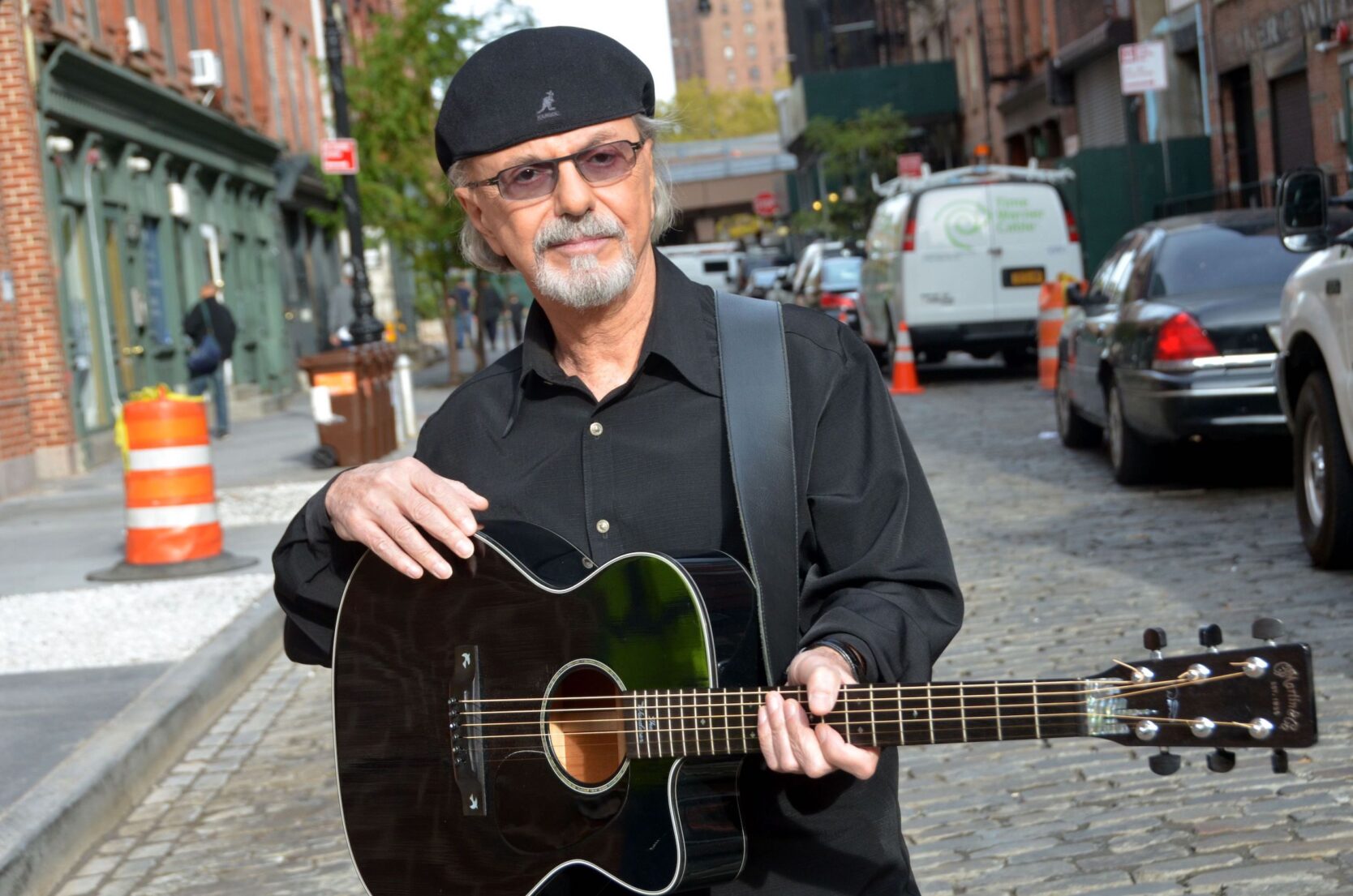

Now, at 84, he has just released his latest star-studded blues album, Girl Friends for Joe Bonamassa’s Keeping the Blues Alive label. It went to No. 1 on the Billboard Blues Album chart.

And The Wanderer, a musical based on his life, opens in New York City later this year.

Ladies and gentlemen—the Bronx’s very own Dion DiMucci!

You’ve recorded three, all-original blues albums since 2020. Why this burst of creativity?

I’ve learned that I can actually ask for help. I was brought up with that “Be self-sufficient” and “Don’t ever ask for help” attitude. But the last four years, I’ve been asking all kinds of people to join me, and they jump at the chance! [Producer] Wayne Hood and I work so well together. I have no anxiety, no nothing. I never knew how enjoyable that can be, that people want to help and be included. To be honest with you, I’m glad I lived this long because I’ve never experienced anything like it (Laughs).

Do you write your new songs with specific special guests in mind?

No, but I can hear their distinctive playing on the song. Like on Blues with Friends, I heard Jeff Beck on “Can’t Start Over Again.” He’s a guitar player that would make me cry, you know? So I thought, “He has to play on this.” Or like when I was doing Stomping Ground, I heard Peter Frampton on “There Was a Time” and Mark Knopfler on “Dancing Girl.”

You’ve also gotten Bruce Springsteen, Paul Simon, Boz Scaggs, Billy Gibbons, and Van Morrison aboard. Your Rolodex must be crazy.

I do it all personally. I just send an email. “Hey, would you like to join me on this song? I think it’ll resonate with you.” And 99% of the time it’s, like, “Yeah, I’m in.”

You also got Eric Clapton.

Yeah. I sent Clapton “If You Wanna Rock ’n’ Roll.” He recorded his part, sent it back, and I loved it. I sent him an email. I said, “Eric, you sound 19 years old on this song, man! Thank you! You really, really crushed it.” He says, “Dion, I wanted to do a good job for you, so I stood up in the studio” (Laughs).

Are all of these duets done remotely?

Maybe half and half.

Why did you decide to make Girl Friends—i.e., an all-female-duet-partners album?

When I was working on Blues with Friends and Stomping Ground, I had so much fun with Samantha Fish and Rickie Lee Jones and Patti Scialfa that when I started putting this album together, I made kind of a left turn. I thought, “Wow! There’s so many great women musicians and singers that I listen to.”

And I’m telling ya, they bring it. They don’t phone it in. Nobody took it for granted. Christine Ohlman’s a great rhythm-and-blues singer. She’s just extraordinary with the depth of knowledge she has in that genre. And Rory Block comes in and does this thing on “Don’t You Want a Man like Me” that almost felt like a When Harry Met Sally moment, you know? In the diner where Meg Ryan is having a climax. When we finished that song, her husband walks over to me and says, “Don’t play that to your wife” (Laughs).

Do you listen to a lot of blues?

I do. I listen to the Blues Channel a lot. And I’m on Joe Bonamassa’s blues cruises with a lot of these new artists.

One of the two non-blues tracks on Girl Friends is your Carlene Carter duet, “An American Hero.” It sounds like a 21st-century “Abraham, Martin and John.”

Right? I was trying to do something like that. “Abraham, Martin and John” basically says, “You can kill the dreamer, but you can’t kill the dream.” People like us will pick up on it and carry it further. There’s a state of love that does exist, and we can put it into action and make it real. The same with “American Hero.” You don’t have to look to cable news or politicians or the tabloids or Hollywood. You can look inside your own heart and be a hero to the people around you—your family or your friends or the people you work with.

Is there anyone that you wish you could’ve recorded with but for whatever reason couldn’t?

Christine McVie. I loved her voice. I wish she was around. I would’ve loved to do something with her. And on “I Got Wise,” I was shooting for Chrissie Hynde. She wanted to do it, but by the time she got freed up and wanted to go into the studio, I’d found Maggie Rose.

Bob Dylan wrote the liner notes for Blues with Friends. He has since written an essay about reincarnation inspired by your and the Belmonts’ recording of “Where or When” in his book The Philosophy of Modern Song. What did you think of that?

Boy, was that way out, huh? The lyrics of that song are awesome, so I could see where he could let his mind go. It took him into a story. His imagination went off on the song. But I love what he said. He said I’m a “bluesman from another Delta” (Laughs). I just said, “All right!” Because I’ve always thought Bob Dylan was a great blues singer. I know he’s a great blues singer, I mean, ever since I heard “Maggie’s Farm.”

Speaking of great singers, you were inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame alongside Otis Redding and the Temptations. How did Lou Reed come to be your presenter?

I asked him. He was a good friend. And he’s a rocker. We probably disagreed on a lot of stuff (Laughs), but I loved his attitude—on guitar and sound and the way he approached things. Something about it was so New York, you know?

A lot of folks probably wouldn’t peg you as a Lou Reed fan.

I’m conservative in a lot of my thinking, but I’m very liberal with my love. I’m a pretty open and non-judgmental guy. I can talk to anybody. Sometimes he would ask me, “Dion, you like that song? You know what that’s about?” And I’d go, “Yeah, I know what it’s about”! He was very irreverent, and he would write anything to get a reaction. But I don’t think he did it for that reason. He wanted to shake people loose to see what was real. And I think that’s why we got along, because he knew I was real.

You had a band for a while in the mid-’90s—Dion ’n’ Little Kings—with Scott Kempner, the ex-Dictators guitarist and Del-Lords frontman who passed away last November. How did you hook up with him?

Somebody gave me a tape of his, and I threw it in my trunk. One day I found it and put it in the cassette player in my car, and the first song was “You Move Me.” I thought, “Man! I like this!” So I got in touch with him. We went out, had lunch in the East Village, where he was living, and got together. We started writing songs and put the group together.

How involved have you been with the musical The Wanderer?

I stayed close to it the whole way to keep it on track, Stevie Van Zandt and myself. It’s rock and roll street history and early rock and roll history. And it’s action—the gangs in New York that I belonged to when I was a kid—and romance. I’ve been married 60 years to this girl Susan. So that’s part of it. And betrayal and overcoming. And there’s a lot of laughs. And the music! It’s a trip. We have a theater, and we’re opening in the fall.

Besides the blues, your career has encompassed doo-wop, rock and roll, folk—even contemporary Christian music. Is there a thread that runs through it all?

You know, as a kid, I heard Jimmy Reed and Hank Williams, and they took me to a place of enchantment. Since then, my whole life has been trying to put together songs like that, and to transmit that feeling.