“This is what happens when you let mentally ill people build their own playground in the desert.”

So says Wizard as we sit at the entrance to East Jesus, an open-air art museum in Slab City. The discarded junk sculptures that compose East Jesus depict ghoulish elephants made of old tires, post-apocalyptic vehicles with mannequin legs sticking off car roofs, doll houses promoting conspiracy theories about Stalin’s relationship to dolphins, and a wooden pirate ship overlooking a 12 foot tall seesaw and a DIY bowling alley.

Wizard serves as greeter for any tourist who wanders into this found-materials MoMA, letting them know that all the art can be touched (and that if they accidentally break something, they should blame it on the next guy who walks through the gates). There’s also a gentle reminder for cash or trash donations, which will help support the artists’ livelihoods or at least contribute to the next sculpture in the park. When I ask Wizard if there’s a common thread that brings people together here, he offers me this:

“Everyone is 100% certifiably insane,” he intones, stroking his Gandalf beard. “And I mean that from a clinical perspective.”

I first learned about Slab City from my mom, of all people. She needed a weekend away from her job in San Diego before a brutal stretch of work, and had heard about cool bird migrations at the Sonny Bono Wildlife Sanctuary near the Salton Sea. It’s only a three hour drive from her place. Because I was soon leaving on a backpacking trip through Cambodia, I figured I’d tag along.

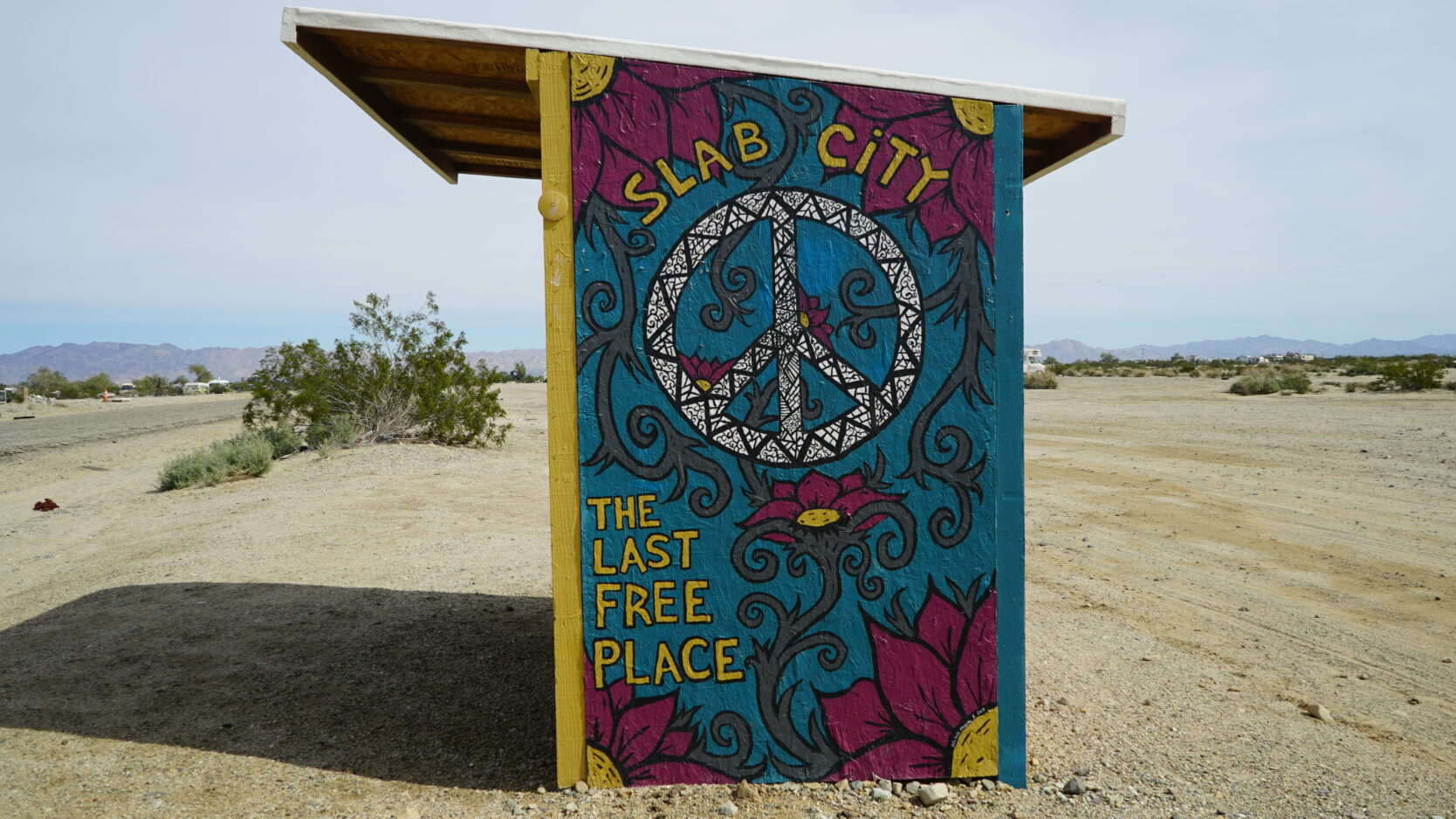

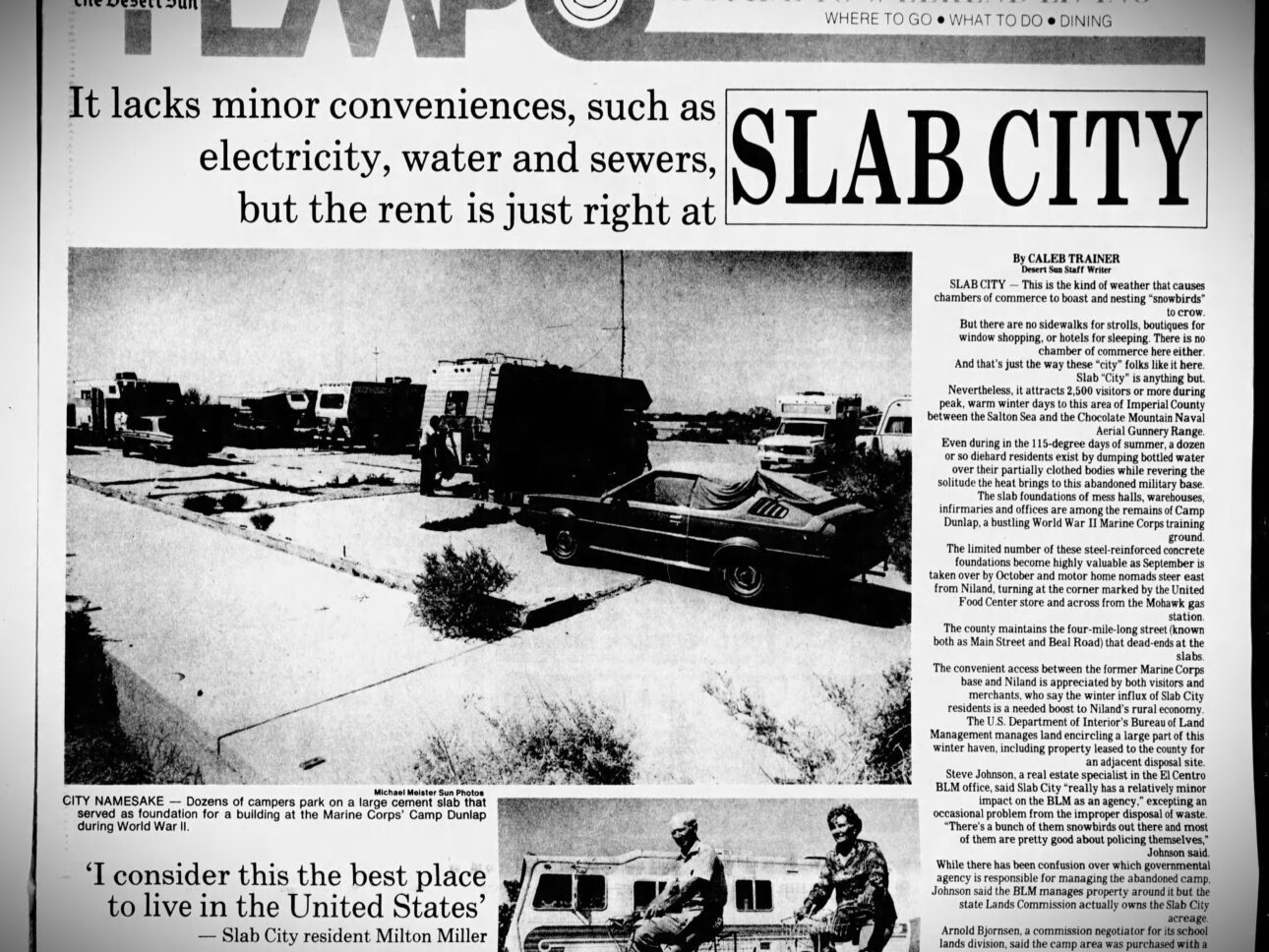

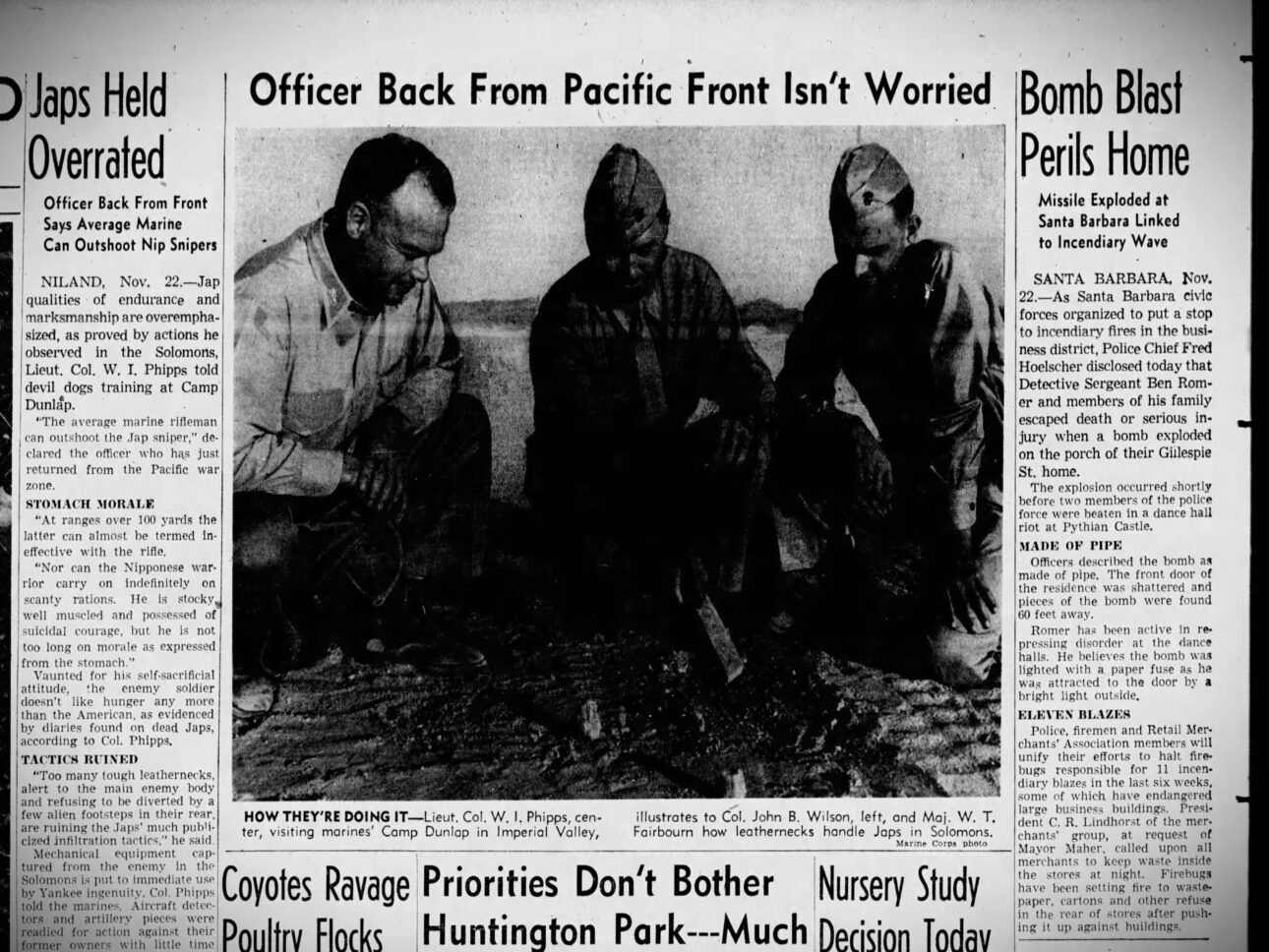

She was looking for places to stay in the area and found an Airbnb somewhere called Slab City. A cursory Google search let me know that Slab City billed itself “The Last Free Place,” with no concept of private land ownership and where an informal economy built on cash, water, and weed ruled the day. A long decommissioned US Marine base called Camp Dunlap, in this century it seemed most famous for an evangelical religious sculpture built into the side of a hill celebrating Jesus, although Emile Hirsch also flirted with Kristen Stewart here in the 2007 film, Into the Wild.

You have to pass through sparse mining towns where the sulfur fills your nostrils and the flatland of the desert is broken only by low-growing plants on dusty farms. Then you pass an ominous factory at the edge of town, cross a cracked bridge, and see a military checkpoint derelict for decades. A hand-painted sign made to look like something out of Las Vegas catches your eye. “Welcome to Fabulous Slab City.”

Right next to this, a burned out car lies in the desert sand. You’re now entering the Last Free Place.

First you pass by Salvation Mountain, which looks like Jesus’ inner monologue during a bad acid trip as directed by Baz Luhrmann. Scattered camps and trailers line the road leading to the Mountain, but only after you pass it does Slab City well and truly arrive.

On the main road you’ll see close to a hundred individual encampments. Most people seem to be living in trailers or RVs, all boasting eccentric artwork. There’s a trailer painted entirely pink with two pink lawn chairs and a makeshift pink picket fence denoting the inhabitant’s informal property line. Someone else has painted their small motorhome in Mondrian squares, while another person has a collection of sculptures made from old tires and decapitated baby doll heads staged in some surreal play. There’s a church that evokes the tower of Babel, and a watering hole called The Range that sports a stage for open mic nights.

Mom and I take a right off the main road on our way to Slab City Hostel. Unfortunately, we quickly realize that we’ve booked a methhead’s RV for our weekend getaway. This might sound rude or crass, but when a high-as-a-kite 40-year-old man wearing an Alice in Wonderland top hat keeps eye-fucking your mom as he shows you around the dust-covered digs you’ll be sleeping in for two days, your wishful optimism starts to grate against why-the-fuck-am-I-doing-this. But there’s not much time to unpack (both literally and figuratively) if we’re gonna see these geese Mom is so excited about before sunset.

Today’s bird show is a bust, but as we return to town we notice the Range lit up against the night sky. Stopping in, we’re greeted by a beer-bellied man in a pink feather boa singing dirty blues with a wire-thin guitarist and a tiny butch woman who looks a lot like Jodie Foster. They’re really good.

Three more acts follow: a gentle voiced young woman crooning Amy Winehouse, three white guys who look like headbangers but play the most enthusiastically strange cover of Ginuwine’s “Pony” I’ve ever heard, and a blonde man who sprints through three Fall Out Boy covers that nobody asked for.

But the main attraction, the performance I will remember to my dying day, closes out the night. It’s four femmes and a young masc who all look like teenage runaways from a bad ‘80s movie. They are Jester Jizz.

Everyone in Jester Jizz wears clown paint and flowing robes. They play ethereal music from a boombox and perform free verse that ruminates on our cosmic origins, the chicken-or-egg question, and the decline of semen quality since 1980.

At one point the four femmes chant in unison: “Semen quality has declined by 60% since 1980. Semen quality has declined by 60% since 1980. Semen quality has declined by 60% since 1980.” The masculine performer stands in the background playing a pan flute. There’s a sweet sincerity to the performance, and the audience is enthusiastic and encouraging.

Towards the end of the set, the Jester Jizz runaways huddle in a circle. I worry they’ll bring up semen again but they change tack, now chanting:

We are the kids of America.

We are the kids of America.

We are the kids of America.

The crowd cheers—the tweakers most enthusiastically. Something in their performance touches me. There’s an urgency, a longing, a desperation in their confession that catches me off guard. These are the children of America, running away from home, holing up in the Last Free Place. What does the future hold for them?

As the tensions of the country keep tightening, as it feels like the water in the pot might boil over at any moment, I think (for a second) I understand where these kids are coming from. Or, at least, I want to understand. Getting inside the headspace of my generation’s runaways in America’s Last Free Place might help me figure out what the hell is going on in our country. And maybe it’s not just these kids, either. Maybe it’s all the lost souls who have made Slab City their home, at least until the summer heat melts the soles of their shoes and they find cooler places to stay.

So let’s see what the future holds for these anarchists, (un)recovered addicts, misunderstood artists, and teenage runaways. Maybe we’ll see something of our future in theirs.

Which brings me back to Wizard and East Jesus. Wizard (who, as a way to separate his personal and artistic selves, goes by Mobar when he’s not on the East Jesus premises) has lived in Slab City six months of the year for 12 years. Originally from Wisconsin, he worked as a drug and alcohol counselor until he “made a bad call” with drastic consequences.

“I sent a guy to jail for a day,” says Wizard. “And while he was in jail, he hung himself. I shouldn’t have made the call. That was about the time that I quit.”

Wizard hopped in his car, fueling it on discarded vegetable oil found in McDonald’s dumpsters (this was back in the ‘70s and ‘80s, when restaurants didn’t put locks on their trash). He went all around the country until he made his way here and pitched his tent. After a few years camping out in the slabs the artists at East Jesus offered him free coffee and breakfast, eventually bringing him in as the museum’s full-time greeter.

Wizard stays working here “because I can say whatever I want and nobody wants my job.” He feels at home among a community of people who (in his mind) all self-identify as insane and want to live in a place where they’re not judged for that insanity.

When I ask whether there are any issues living in Slab City, he mentions Bad Thing. “So you’ve been here too long, maybe six months. After a while weird things happen to your head. It’s this nasty little spirit called Bad Thing. Bad Thing gets into your head and you have negative thoughts and they spiral. It’s just like a buzzsaw, only it’s really, really cold.”

What happens when Bad Thing shows up, I ask. Wizard thinks for a moment, smoking his pipe. He mentions that if people get too crazy out here and start bothering others or stealing, they get burned out. At first I think he means metaphorically, but no.

“Eventually, if someone is too annoying, they’re simply burned out of here—their camp is burned down,” Wizard says. “I always make it a point that no one is hurt, no lives are lost, no one is home when they’re burned out. And you never burn the vehicle, because you want them to leave.”

This seems to be the main method of expulsion in the Slabs, especially when you’ve pissed off a good chunk of the community. It’s an undercurrent of darkness that punctuates the singular weirdness of this place. You’re allowed to be yourself, so long as you let others be themselves—otherwise you’ll be burned out and banished back to Babylon (as Slabbers refer to the regular world).

Wizard has to get back to greeting tourists, but before I go I ask if he knows anything about Jester Jizz. He doesn’t, but he recommends I talk to Dot.

Dot’s House of Dots sits directly across the road from East Jesus, and is a tourist attraction in and of itself. Five trailers sprawl out in a labyrinth of surrealist artwork, skeletariums, and gift shops. Dot, the 51-year-old woman who runs the place, shows me around. First stop: Taxidermy Dinner Party.

Inside this trailer we’re greeted by a trio of deer heads sitting around a circular dining room table. Plastic human remains lie on a big plate, as the youngest buck informs its parents that it accidentally struck a wild human on the road. It didn’t want to waste the meat, so it brought the dead human home and cooked it for dinner. The parents, both wearing ornate jewelry on their antlers, are proud.

In the middle of the trailer lies the Plague of Christianity, a menagerie of twenty spray-painted rats and crosses. Next to it sits the Barbie Whorrer House, a tableau depicting three Barbie girls who make their way to a haunted dream house and end up murdered or turned into pigs. At the room’s far end a still-life sculpture depicts a deformed woman birthing deformed babies after cats have taken over the world by implanting a parasite inside human brains.

After this we head to the Skeletarium. A fridge inside the trailer displays animal bones on tiny dishes, in addition to a few snake and spider carcasses. A Party City skeleton nearby is dressed in occult robes, holding a crystal ball and offering a fortune reading.

Finally, Dot takes us to a school bus she’s converted into a thrift store. Rows of junked or used clothes line hangers, with a graveyard of dusty shoes collecting outside. It’s a popular spot for Slabbers to find new clothing or barter goods, especially if those goods are water or weed (two of the most valuable commodities in the community).

Dot’s from Ohio, where she worked in IT for a few decades. She says her neighbors there harped incessantly on the daffodils and purple-flowered weeds in her yard. It got on her nerves, so she packed her stuff and moved to the Slabs. Unlike Wizard, Dot stays here year-round. “I love it. I get to be my full self here.”

Rich, who’s temporarily posted up on Dot’s property, echoes this sentiment. Rich didn’t do well in school, he says, flunking his classes and never fitting in. After his second year of high school, he squatted with a crew of punk crockers in Manhattan’s Alphabet City, immediately feeling at home. Eventually, however, he started a family and moved to Colorado, but now that his kids have reached an age where he feels they can live more or less independently (they’re 15 and 17), he’s come out to the Slabs. It reminds him of the old Alphabet City squats. Natural environments aside, the cultures of the two free-wheeling zones are “exactly the same,” he says. “Just a lot of outcasts,” Rich tells me. “I made the move three months ago, and I immediately knew I was home: the people, the sense of freedom, the lawlessness….” He stops, catching himself. “I shouldn’t say lawlessness, more self-governance. Don’t fuck around too much. Just keep yourself in check.”

I press him on whether he’s faced any significant issues moving out here but he shakes his head, pointing to the Slab City Soup Kitchen, morning coffee at the Oasis, and the book collection at the Library as proof of the support the community provides. Then he catches himself again.

“Well, there was the first night I came here. You know about Ponderosa?”

I nod. It’s a pay per night campsite where I can sleep in my car if I want.

“That’s a nice place,” he continues. “I stayed there my first night too. I hung out by their fire for a while, and then I went for a walk around the slabs. It was dark as fuck, but I had my big Maglite and some bear spray just to watch my ass, you know. So I go for a walk in the dark and this fucking crazy methed-out dude carrying an ax approaches. And the fucking dude is like, ‘Who is that? Who is that?’ And I’m like, ‘My name’s Rich, dude. I’m not looking for any trouble.’” We’re like 50 feet apart and getting closer. He’s like, ‘I want to chop you up into little pieces,’ and then he fucking comes at me with the ax. I already had my bear spray in one hand and my Maglite in the other. But I’m thinking to myself, bro, I’ve been here like three hours and I’m gonna have to fucking kill somebody? So what I did instead is I backed up and ran up the road just a little bit. It was dark as fuck, so I didn’t have to run too far. I ran and I saw a little space where I could hide, and I turned off my flashlight. I hid behind some shit and I was like, if this dude even turns in my direction, I’m gonna spray him. I’m gonna fucking beat him down with the flashlight. But he didn’t. He kept yelling ‘Holy shit!’ and just walked past me. It felt like that scene in The Shining.”

I nod. Guess I shouldn’t wander around the Slabs at night.

This trip is without Mom, so I find Ponderosa and pay $10 to car-camp for the night. Afterwards I amble back to Salvation Mountain and take some golden-hour pictures. Then it’s off to the Range’s open mic to see if I can find Jester Jizz.

From the jump, I can tell there’s fewer young people than last time. Apparently there’s a desert rave somewhere past the Mountain that a bunch of Slabbers are trying to crash, but you need a sturdy 4WD to make it through the crags and dried up canals. I settle in, hoping to get lucky.

Builder Bill, who’s been here over 20 years and helped mix the mud used to construct Salvation Mountain, takes the stage first. He started the Range when he first arrived and has managed it ever since. He has a decent enough voice when he’s not coughing through emphysema. He finishes the set and admonishes the state of our nation, saying he predicted things would fall apart when the second plane crashed into the Twin Towers. A few people raise their eyebrows, and a large-bellied man sitting next to me mutters that Bill’s really on one tonight. Then other musical acts take to the stage.

For the most part everyone’s singing gentle acoustic covers. A young man emanating Very Serious Artist Energy can’t play because he can’t hear himself back in the monitors, holding up the music for thirty minutes trying to fix it. The pink boa guy from last month sings the same set I heard with my mom, and a young couple sings sweet love songs.

Then Daddy comes to the stage, and the first two rows of the Range clear out.

Daddy’s wire thin and missing teeth, swaying, and talking in nervous staccatos. Someone yells at him from outside the Range and he responds in kind, shouting: “Fuck you, Dreamcatcher!”

Then he plays.

He’s got a pleasantly weathered folky voice. He performs “Something in the Way” by Nirvana and then a cover of Wu Tang’s “C.R.E.A.M,” swapping out crack for meth and Staten Island for Slab City. He finishes to tepid applause and takes a seat in the front row. I sit beside him and ask if he’d speak with me. He needs to find some rolling papers but he’ll meet me out by the parking lot. He speaks the way he sings – jitterbug staccato, Joker laughs, swaying in circles.

We meet in the parking lot and he tells me to follow him out to Free Slab, where it’s less noisy. Two dogs yip at each other around his feet. He’s carrying a guitar, a long pole, and two or three hoodies. He won’t stop talking, assuring me he knows the Slabs like the back of his hand. He’s leading me further and further into the darkness, away from any sign of people, and I’m getting nervous. I remember Rich’s methed-out ax wielder, wishing I’d brought bear spray. The barking dogs scrambling around our feet don’t really help.

We finally reach Free Slab, so called because people place their donations for Slabbers here. It’s an old cement basketball court near the center of town, about 150 yards from the Range. The music echoes to us over the wind, but we’re the only two people in sight.

Daddy drops his things. I ask a few questions, but he’s talking so much that I mainly just listen and try to steer the conversation to a more coherent narrative.

“I grew up in the Bronx during the burning period—in the 70s and 80s there was a housing crash, and the buildings were worth more for the insurance money to the landlord torching it. If

you told me when I was 12 years-old that one day you’re gonna live in an abandoned pool that you turn into a skate park with your friends, I wouldn’t have been surprised, you know?”

I nod.

“People don’t care out here but I was a college professor in Times Square [at] New York Digital Film Academy. My specialty is artificial intelligence, actually. Computer science. I also worked at NBC, Syfy Channel, I worked on 30 to 40 TV shows. ”

I ask whether there’s been any issues living in the Slabs.

“There’s a horrible rumor mill here,” says Daddy. “Like, terrible. You have a lot of mentally ill people here. You have a lot of drug addicts here, who also tend to be paranoid. I’ve been accused of murder a couple of times, and that’s scary to me. Even though it’s the opposite of true, somebody might believe that or maybe some kind of mob justice will happen. I personally believe if people start those rumors, they do it to obscure the truth. Like who’s a real pedophile? If you call everybody a pedophile, or you call everybody a rapist, it obscures the real villains and it also, the biggest tragedy is the disservice to the victims. I mean, somebody accused me of being a necrophiliac, because I was making out with a dead person. I’m like it’s mouth to mouth CPR, I’m trying to save the guy’s fucking life. Like what the fuck?”

The wind howls around us and the dogs bark. I can’t tell whether Daddy is harmless crazy or murderous crazy. The fact that he took me to a concrete slab in the middle of nowhere isn’t helping.

You’ve been accused of murder? I ask.

“That’s why the rumor mill doesn’t bother me,” he replies. “I’ve got seven fucking CPRs. I saved a baby’s life. Family publicly thanked me right in front of my house a couple years ago. So let them fucking hate, you know? But it’s unfortunate because it makes life so difficult.”

Is that why Dreamcatcher yelled at you?

“She thinks I did something with a girl even though I was the only person in this town who didn’t fuck her! She had a man and he came to hurt me but I told him we’re just talking, I’m not doing anything untoward. He can knock down my door anytime I’m with her ‘cause I’ve never been naked around her. I don’t even shit around her because I wouldn’t take a shit in the presence of a lady. He did that twice and saw it was true and so he knows. But it’s the rumor mill, man.”

I try to nail him down on specifics but Daddy keeps spiraling, looping back to saving people, CPR, people dying not being his fault, never touching someone wrong, being a genius in New York. He sways and paces and his hands are in his pockets and sometimes he steps towards me but then staggers away. The dogs keep barking shrill in the night and someone’s singing “Life is a Highway” back at The Range and Daddy won’t drop this murder train of thought but he won’t give any specifics and the hairs on the back of my neck are standing on end. I need to be surrounded by people but every time I try to exit Daddy swoops me back into the conversation or staggers around to my side to keep me talking. I don’t get the sense that he means me any harm, but I also don’t get the sense he’s stable, and I’ve gotten all the honest information from him that I can.

Finally he asks if I want to see his house—just past Salvation Mountain, a 15-minute walk through the dark and away from the center of town.

“It’s a pile because I’m rebuilding from the fire. But if you look closely and come inside you might be able to see I do a lot of service.”

I thank him but say I have to get back to the Range and talk with some more people, but maybe I’ll see him tomorrow?

“Oh yeah I’ll be around tomorrow. I’m an open book, you can ask me whatever you want, take pictures, I won’t pose for anything but I’ve had cameras follow me around before. I can take you wherever you want to go. It’s not much, but it’s a home and I make it work. I’m rebuilding those trailers, sometimes fires happen, what can you do?”

I thank him again but tell him I really do have to get going, and he finally ducks away and picks up his guitar and the 6-foot pole he carried out here. He yells at the dogs to get away and then I’m beelining back to the Range, looking over my shoulder. I take a quick glimpse inside to see if Jester Jizz is back but there’s no clowns to be seen.

The kids of America will have to wait until tomorrow.

“Dude, at the rave last night I saw two girls peeing on each other.”

Laz (short for Lazarus) lifts his legs up, demonstrating how the girls were positioned spread eagle on the ground as they peed together. Carlos laughs while he clips his toenails and Karen gently protests, shooting a glance at my camera. “Swear to God, dude. I couldn’t believe it, out in the desert.”

“I don’t remember that,” says a man who recently woke from sleeping facedown on the concrete of the Skate Shack. His vest sports shoulder pads made with anti-homeless spikes he found somewhere in Chico.

“You must’ve been out by that point,” counters Laz. “They’re probably the ones who brought you home last night!”

I’m hanging at the Skate Park with a couple of thirtysomething BMX enthusiasts. The park itself looks like Tony Hawk Pro Skater meets Mad Max Thunderdome, complete with handmade ramps, halfpipes, and a burned-up car that the crew habitually lights on fire for jumps on their bike. It’s a five-minute walk from the Oasis, a morning cafe that serves coffee and fresh breakfast most days, supplies allowing.

I arrived at the Skate Park about an hour earlier, because I’d heard there was a BMX festival going on this weekend and I might run into more young people there. When I arrived, all I found was the aforementioned shoulder-pad man passed out on the concrete, and Laz hanging out on one of the ripped-up sofas.

“You here for the festival?” he asks.

“Yeah, to take some pictures,” I reply.

“It’s been dead this whole weekend,” he says. “Only 5 people came out this year.” The past two years the festival had upwards of 100 people come out and rip along the wood ramps and concrete half pipes, riders launching naked over the burning flames of the brown carcass of a car in the center of the pit. But there was a rival festival going on in Florida that might’ve dwindled the pool, plus the desert rave probably sucked some of the audience away.

Laz and I make polite conversation about the construction of the park, which was hand dug, filled, and molded by seasonal Slabbers and pro skaters from El Centro. While we talk, he searches for fresh tobacco, eventually picking up from the ground a half-smoked, trampled cigarette, rolling the remnants into his own paper.

“I’m about to roll the most disgusting cigarette ever, bro,” he enthuses.

While he does this we talk about what draws him to Slab City. He’s seasonal, not a year-rounder by any means, but he says it’s the people and the culture of freedom he loves most. “There used to be a bar called Handle next door, but someone burned it down over the summer. That shit happens, man. The summer drives people nuts.”

Carlos and Karen arrive shortly thereafter. Carlos and Laz are both in their thirties, and talked online for years before coming out to Slab City together. As Laz puts it, “I met him one night, let him crash, did some lines of Xanax and coke in the morning and told him we should head out here. That was eight years ago.”

Carlos jogs up and asks whether I plan to jump the car naked. When I decline but say I’ll definitely watch someone else do it, he frowns. He tells me he would, but he’s kinda dead from all the partying yesterday, plus no one’s showing up for the festival. Then he goes around scavenging among the beer cans for any that might still be full from last nigh.

Karen introduces herself next. She’s calmer and more lucidly on the level than Laz. She’s seasonal as well, living the van life as she hops from place to place around the country. She and Carlos met in the Bay Area in 2019, and have been traveling on and off together ever since.

“I just like the people out here,” she tells me. “There was a great scene before the bars burned down, but there’s still a good crowd here in the winter.”

Laz pops a beer can that’s still full.

“This is gonna be the most disgusting, flattest shit ever,” he opines before taking a swig. Then he points to the fridge in front of him, littered with cups and other random items. “Did you see what someone brought yesterday?” he asks Karen.

“What?” she responds.

“Fucking fentanyl test strips, Narcan, and condoms. Like dude, what does he think we’re doing?”

“I mean, you never know,” she replies. “Somebody might get laid.”

“Those test strips don’t work,” says Laz. “I once did like eight lines of coke at a buddy’s house and was totally fine. He tested it the next morning and it came out full fentanyl. Like, that’s not possible, or else I have a superpower.”

“Oh, wow,” mutters Karen, a little concerned.

Carlos rushes back in, a half-slugged warm beer in his hand. “Welcome to the BMX festival!” he shouts. Everyone laughs.

I ask them about their backstories. Laz has a grandmother he’s really close with living out in Chico, and he bounces throughout Southern California BMXing and doing drugs. He smiles for me, revealing a top gumline where only three teeth remain dangling.

“Busted them up riding off a roof. Smashed my face. That’s why I barely have any teeth,” he laughs.

Carlos and Karen have traveled all across the country. They got as far as New York City, where Karen found a fantastic spot to park her van right near McCarren Park in Williamsburg. Sixty dollars a month for the spot and a community center nearby with showers. Carlos found a spot in Long Island underneath a highway overpass, but he liked it because he could walk up to shit in the woods. Karen didn’t like the traffic constantly passing by. Carlos agreed big 18-wheelers would come whooshing by and you’d see your life flash before your eyes, but he still thought the location was prime.

They all agree that the people and sense of freedom in Slab City is what keeps bringing them back, especially the Skate Park. All of them lament the burning of bars over the last summer, chief among them Handle.

“It was an awesome spot, but a lot of people were doing drugs and camping out inside the bar,” Karen tells me. “Guys with needles in their arms knocked out all over the place. Apparently they got in a fight with someone over the summer and they burned it all up.”

With burnouts on the mind I ask whether any of them knows about Daddy and his trailers that keep catching on fire. Laz is the only one who replies.

“Daddy’s annoying, dude. I don’t know of anyone who has anything actually bad on him, but he just gets on people’s nerves. You’ve seen his place? It’s a mess.”

The guy passed out on the floor finally raises his head from the ground and jumps right into the conversation. Soon everyone is huddled around the couch, debating the merits of ketamine and swapping stories from the rave.

I ask if any of them know about Jester Jizz, but they shake their heads. There’s one more camp which might finally have the answers I’m looking for, so I thank the skaters for their time and head back toward East Jesus.

Flamingo Camp is positioned across from Dot’s, forming a pseudo Arts District. It’s designed as a safe space for queer slabbers, and although membership doesn’t require queerness, most everyone who stays there is queer in some capacity.

I saw campmates leaving for yesterday’s rave in some pretty fancy regalia, so I wonder if they’ll have an idea who those kids were.

At first, the camp is a little reticent to talk. They seem more media savvy than other people I’ve met out here, and they’re understandably leary of anyone with a camera. A trans man was murdered in the Slabs back in 2021, and although it’s not explicitly stated, I gather that may have given some of the campmates pause as to a fully open-door policy. But once we talk for a little while, they agree to speak.

The first person I talk to is Little Bear (preferred pronouns they/them). They’re a caterer for movie and TV productions in Los Angeles, but come out to Flamingo Camp as often as they can. They find the stripping away of the inessential liberating. They also like living in a safe space for queer people. Campmates check in with one another, organize activities, leave space for people to exist. Little Bear had trouble finding that in the city, they say.

They also take pride in community events that Flamingo Camp organizes, such as self-defense workshops for the Slab’s children and queer people. When I ask whether there’s been issues with older Slabbers, Little Bear shakes their head.

“I mean, certain people will always treat you differently, but it’s no more than anywhere else I’ve lived,” they respond. “Plus, the community we have at Flamingo Camp is great, not to mention places like Ponderosa or the Library.”

Sunrise, another campmate at Flamingo, agrees.

“There’s an openness to be yourself here that I really enjoy,” they say. “Plus we have activities every week, like Brunch Bingo and dances, which really bring people together. I was an arts development manager in Detroit for seven years, so to be able to do that kind of work is really a joy.”

Little Bear and Sunrise are both seasonal, as are the majority of campmates I speak with. The founder of the camp, Mars, sometimes stays year round (but they’re not available to talk to during my weekend in the Slabs).

Flamingo Camp strikes me as the most chill, put together encampment in Slab City, a site that focuses less on individual anarchic self-expression than a communal, co-op living situation in an area that’s basically off the grid. They all share a similar story of avoiding queer persecution in the regular world to form this safe space in the desert, but there’s not the same sense of the “wandering refugee” mentality here as there is among the old heads (as Builder Bill once put it to me over morning coffee at Oasis). In that sense, Flamingo Camp stands apart from the other areas I visit in the Slabs: a greater sense of communal cooperation.

But none of them know Jester Jizz. Sunrise recalls someone mentioning a crazy performance last month, but can’t remember the specifics.

I thank them for their time and head out. I’m feeling light-headed. The desert heat is getting to me.

But I have one more place to visit before I can call it a day. A house call I promised to make during a windy night at Free Slab.

I spot the telephone-pole cross a few hundred meters from the entrance to Salvation Mountain. Two burned out trailers and a pile of junk extend around the perimeter, with what looks like a bunker of trash lying a few paces beyond.

Daddy’s messing with some wires in the front yard and he’s got a friend sitting on an old car seat turned living room chair in the main area. I approach and say hi.

“Hi man, hi. You got any water?”

I return to my car and pull out a bottle of water. Daddy asks for half, but I give him the whole bottle. I figure he needs it more than me. He leaves a little for his friend, who’s messing with a copper wire on the chair and introduces himself as Nobuddy. I ask how he came to Slab City.

“I came here on a hippie bus, chasing rainbows. Didn’t really like it. Don’t really like it here, but I’ve been here over ten years now. Stay for the drugs.” He chuckles. I ask what drugs specifically. He just shakes his head.

“Oxygen, man. Fumes in the air. I saw a face in the sky, burning face with fire all around it. I wasn’t even high, totally sober. It told me this would be a good place to kick it, so I figured I should listen.”

Daddy passes by muttering something under his breath while he messes with exposed wires. I ask him what he’s doing.

“I’m trying to fix my amplifier, so I can play music and blast it over the speaker. It was working yesterday but something happened to it, so I’m using this busted solar panel, hooking it up to this car battery, the kind you can use to jump a car, and seeing if I can wire it through the speakers.”

Daddy’s walking around barefoot on the hot desert sand, but it doesn’t seem to bother him. He decides he needs a bigger solar panel for the project, so he trudges over to the big trash bunker. I ask what the bunker is.

“It’s where I sleep. Wanna check it out?”

We walk toward an old iron gate with a stop sign wedged in the bars. Daddy pulls it open and we step inside, where I’m greeted by morasses of discarded junk. Daddy considers himself a technical wizard, so he has boxes of old laptops, cell phones, wires, radios. Even the living quarters used to be a technical enterprise.

“Yeah, this is a late ‘80s German NATO patrol, think they called it a forward transport. It would patrol the Soviet Bloc in West Germany and intercept and send signals to the troops. Lot of people wanted it for years, but I was able to get it.”

I peek in and his claims seem legit. There’s military signage covering the camo exterior, and it’s pretty roomy inside. There’s a bed and some dressers piled high with old clothes. What I mistook for a trash bunker is just another pile of junk strewn on top of the forward transport’s roof.

“Yeah, I’m fixing the two trailers up front, so I’m staying in here right now,” he says. “I’ve had all three of my trailers burn, but I tell myself there’s been 50 families who’ve passed through there so they’ve gotten good use, that’s a good lifespan for a trailer, you know? It’ll take a little while to fix up but I’ll get there.”

Daddy picks up the larger solar panel and trudges back to his outdoor laboratory. I follow him out but I’m developing a severe headache and feeling foggy around the temples. Maybe these are the fumes Nobuddy talked about. Or maybe I’m starting to catch Wizard’s Bad Thing.

I ask Daddy if there’s anything else he wants to discuss.

“I don’t know man. We covered a lot. I just think, the nice thing about the Slabs, is nobody cares. They don’t care whether you were a genius, they don’t care what you did in the past, or, or, or, or what brought you here. It’s just you get to be you. You treat people well, they’ll treat you well too. And they’ll leave you alone.”

He keeps on spiraling, and the more he spirals the more I can tell he truly, desperately, wants to be a good person. He keeps reminding me of lives he’s saved through CPR, families he’s sheltered in his trailers, even students he taught in New York City. But every conversation loops back to the murders he’s been accused of, the ones he insists he hasn’t committed. It keeps jutting against the rim of his brain, forcing its way to the surface. The cold buzzsaw of Bad Thing creeping into the consciousness of a full-time Slabber.

Nobuddy nods throughout this whole monologue. I ask whether he has anything to add, but he shakes his head.

I look at the side of the trailer above him. Daddy’s scrawled out a message. It reads:

DEAR PERSON WHO IS

STEALING FROM ME,

I WILL FIND YOU, AND

I WILL BREAK YOU.

FREINDS WON’T STEAL

ITEMS CRITICAL TO A FREIND’S

SURVIVAL, SO I DON’T CARE WHO

YOU ARE. I. WILL. BREAK. YOU.

– DADDY

The fumes of Bad Thing are getting to me. I need a break from the shared insanity of this place or I might lose it. Plus, I gave my last water bottle to Daddy. I hop in my car and head for Babylon.

Salvation Mountain juts out candy-colored in my rearview mirror. Tourists walk and gawk at it, taking selfies. Some of them will venture further into the Slabs, but most of them will turn around and head back to Babylon.

I never found Jester Jizz. Maybe they were just passing through for a weekend, maybe they didn’t want to be found, or maybe I didn’t work hard enough to find them. The kids of America remain a mystery to me.

But Slab City, even though my stays were short, doesn’t. I’ve never spent time in a place where the level of shared insanity vibrates at such a high and constant frequency. Some of this insanity (a lot, in fact) seems pretty harmless. Dot makes her eccentric art, Rich relives an Alphabet City adolescence, Karen and Carlos live the van life, Little Bear forms a queer community with their Flamingo campmates. Even Laz keeps to himself and does his drugs.

Then there’s Daddy living in a decommissioned forward transport, battling rumors of murder and necrophilia. Wizard running away from the ghost of a man hanging inside a Wisconsin jail cell. The burned out skeletal homes of slabbers who got on too many people’s nerves.

I can feel Bad Thing creeping up over my shoulder, the cold buzzsaw Wizard described serrating my brain, digging for the craziest part of me it can find. I’m new, uninitiated, can’t hack it. I’m not built for the anarchic individualism of the Slabs.

I hoped finding Jester Jizz would teach me something about the state of America, or at least help me better understand the mind of those teenage runaways debating the chicken and the egg while they played pan flutes. Instead I found a city where the most insane corners of the country congregate, form incredible art, organize their own soup kitchens, and build their own libraries. They also take copious drugs, get into fights, and burn down the homes of people who’ve overstayed their welcome.

For all of this insanity and chaotic individualism, the Slabbers seem happier here than in our world.

I’m reaching the end of the road in Slab City. The old military checkpoint stands against the clear sky; the burned-out car lays dead in the sand. This time, the tag on the checkpoint’s wall doesn’t serve as a welcome. Instead, it offers a warning. “Reality Ahead.”

For the first time in a long time, I’m grateful to come back to Reality. Even if that Reality is Babylon.