As The Downward Spiral turns 30 this year, it still stands as an act of artistic transgression against the limits of popular music and as one of the major alternative records of the era to achieve mainstream success. Pushing the boundaries of creative censorship, it is still considered Nine Inch Nails’ most daring and uncompromising album.

When researching my 2019 book, Into The Never, about the making of The Downward Spiral, I was able to dig deep on the past, present, and future of Nine Inch Nails. For this article, I combined the extensive background I covered in my book with new, exclusive interviews with Flood, Alan Moulder, Sean Beavan, Brian Pollack, and Andy Kubiszewski to discuss their memories of working with Trent Rezner.

In the opening track, “Mr Self Destruct,” we hear a prisoner being beaten with increasing force, a sample from George Lucas’ 1971 film, THX1138, setting the tone for the record’s raw physicality. With lyrical themes of mental health issues, drug abuse, BDSM, and suicide, the record holds up a mirror to the perennial growing pains of “lost” generation Gen X, remaining as relevant today as when it was released in 1994.

With the full backing of Interscope label boss Jimmy Iovine, Reznor was given free creative reign and a budget to build his own custom studio (as well as bringing along John Lennon’s mellotron, as heard on “Strawberry Fields Forever”). The album would become notorious for his decision to record at the sprawling bungalow on 10050 Cielo Drive, the house where a pregnant Sharon Tate and five other people were murdered on August 8, 1969 by Charles Manson’s followers. Reznor would christen it the “Le Pig” studio, in reference to the word “PIG” being scrawled on the front door in Tate’s blood. Reznor later took the door with him as a grisly souvenir.

Flood, the album’s producer, who admits to his own fear of ghosts and hauntings, noted a strange ambience in the house as he entered through its large barbed-wire topped gate, telling me: “There was definitely something about it.” Situated in Benedict Canyon, overlooking Los Angeles, the land of sunshine was of little interest to Reznor and his crew, who blacked out the windows and kept nocturnal hours—according to Flood, “isolated by choice”—often working until dawn. Mixing engineer Sean Beavan remembers emerging from the house at dawn to sit down for a coffee with Flood and admire the view of the city below.

As has been widely reported, Reznor still claims he had no prior knowledge of the house—he simply picked Cielo Drive from several houses he saw that day because it afforded him enough space to build his own studio and install live recording rooms. It was only upon spotting a legal notice in the rental agreement that he discovered the house’s dark and tragic history. Every day morbid tourists would turn up, interrupting recording sessions looking for a tour of the house. Flood remembers that, on the anniversary of the Manson Family murders, the band decided to get out of the house for the day, and when they returned they found the street in front of the gate covered in flowers.

The producer encouraged Reznor to work on demos for the album recording, looking for at least eight tracks as a jumping-off point—he was blown away by what he heard: “The songs were already there.” Many parts from these demos were already deemed perfect as-is and would be cannibalized into the mix of finished songs. Beavan admired Alan Moulder as a great listener who could “focus on what was good in a song and know how to make it great”—he would add the reversed drumbeat intro of Iggy Pop’s “Nightclubbing” and suggest the final piano coda of “Closer.”

Flood remembers there were points of friction where he chose to remove himself from the process, like trying to complete the now-iconic chorus of “Closer”: “I hated the [initial] chorus. It was a load of power chords […] It sounded plain. I kept digging at Trent, and so I went away, left him to it, and that prompted him to sample a load of insects, which ended-up sounding like strings. And that was it—brilliant.”

Elsewhere, he objected to the falsetto verse and onslaught of distorted guitar smothering the chorus of “Heresy” and found songs like “Hurt” too straight, like a ballad; it would be completed much later in the mixing stage. Flood says: “The producer or bandmate doesn’t necessarily get it right. Sometimes it’s about the friction between artist and co-conspirator, and Trent would say ‘Fuck you, I’m going to do it anyway’—and that would be for the best.”

Reznor was keen to embrace a number of influences that moved beyond the unwieldy label of industrial music. Although he often mentions Scary Monsters (And Super Creeps) as his gateway David Bowie album (with “It’s No Game No.1” sampled on 1992 track “Pinion”), Flood remembers talking at length with Reznor about 1977’s, Low, choosing to embrace Bowie’s pull-the-blinds-down-and-fuck-‘em all attitude (as Bowie described his situation to one journalist at the time). This inspired a renewed sense of creative freedom, Flood says: “If we wanted to make a song that was two minutes of white noise—we did it—the idea was to let each track be what it wanted to be.”

The Downward Spiral echoes Low’s dual-sided structure—one side for night, one for day— and blends neo-blues funk, jarring vocal melodies, and wordless instrumentals. Reznor took this ambition further still: Individual songs are punctuated by hard-tack changes of direction—from fast, thrashing guitars and punishing drum beats, to moments of slow-burning ambient and piano interludes—becoming the sound of a mind at war with itself.

Flood refers to Bowie’s ability to create arty records that bring the avant garde into the everyday, with hits that anyone could hum along to, reflecting Reznor’s own pop nous. With a goth-disco crossover hit like “Closer” and the torch song of “Hurt,” set against more experimental songs like “Eraser” and “I Do Not Want This” that make manifest rage and suffering, The Downward Spiral neatly bridges the the agitated synth-pop of the band’s ‘89 studio LP, Pretty Hate Machine, and heavily-processed metal guitars of 1992’s Broken EP, showing Reznor could produce hooks and anthemic choruses just as easily as he could sheer walls of sound. Alan Moulder explains: “The idea that you’re making pop music is very important to Trent, because pop means ‘popular.’ So it may be confronting, but it’s not pushing the listener away.” Flood notes that other musicians in the alternative arena were either unable or perhaps afraid of making their music accessible, seeing the popular element as somehow inauthentic: “Making good pop music is really, really hard.”

As an assistant engineer at Cleveland’s Right Track studios in the late ‘80s, Reznor would spend long nights after-hours crafting ideas for Pretty Hate Machine, yielding what co-producer Flood called: “the best set of demos I’ve heard.” On The Downward Spiral, Reznor creates a ruin by design that further confronts the listener, embodied by Russell Mills’ iconic cover artwork, “Wound.” Pieced together from blood, rust, and crushed insects, it would reflect the album’s scar-damaged aesthetic of overwhelming sensation reaching the limits of self-destruction. The recording team took a broad approach to sampling, chopping up, and manipulating tracks while blending in audio clips from horror films such as Texas Chainsaw Massacre. Chris Vrenna “watched” hours of movies with the screen covered, searching for new sounds—and these samples added atmosphere to help create a musique concrete pastiche, as Flood explains: “Every single overdub was thought about. Everything was an artform.”

Although frequent collaborators Flood and Moulder didn’t cross paths during recording, the latter was present for mix engineering at the Record Plant studios in Los Angeles. He remembers trying to finish “Ruiner”: “A bastard track, it fought us the whole way—it was one of the hardest mixes—getting it to do what Trent wanted.” Reznor himself said that it was two songs forced together, eventually bridged by a guitar solo in the inverted style of Pink Floyd’s “Comfortably Numb,” after which Reznor returned to the album’s defiant refrain: “Nothing can stop me now.”

Engineer Brian Pollack reflects how Reznor would continue to add and take away from the final tracks right up until the end of the mixing process: “I was always on the move. You always have to be ready with microphones, getting everything set-up: guitars, pedals, keyboards—for when Trent wanted to record a new idea that came into his head, or using a computer with the first Pro Tools editing software to make a sound dirty or clean.” Trent invited former bandmate Andy Kubiszewski, co-founder of Exotic Birds and now Discotheque, to play drums on the album’s title track, “The Downward Spiral.” Kubiszewski gave it his best shot trying to meet Reznor’s demand to “make it shittier,” playing looser and breaking out of time, enacting the sound of chaos that would segue into “Hurt,” Polar opposites, the tracks “Big Man With A Gun” and “Hurt” were recorded as an afterthought at A&M Studios with Beavan, borrowing Bob Seger’s vocal booth set-up. “I was sat in the booth with Trent singing the vocal for ‘Hurt’ in three takes,” Beaven recalls. “Each one slightly different, right in front of me, with tears streaming down my face.”

Shortly after, Motley Crue’s Tommy Lee (credited for creating a notorious porn-star sample dubbed “steakhouse” on “Big Man With a Gun”) dropped into the studio. Blown away by “Hurt,” he demanded a cassette and then insisted on taking the band to his “office,” a strip club across the street. Beaven remembers Lee disappeared and slipped the cassette into the club sound system, before inviting over several dancers to give the most surreal striptease of their lives.

Using ideas lifted from his lyric journals, Reznor imagined a new mind in which to pour all his deepest fears, doubts, and resentments. “Heresy” attacks organized religion through Christian fundamentalist response to the AIDS crisis, exploiting the Nietzschean maxim of “God Is Dead.” Further embracing misanthropic alienation, towards the end of the album “he” sinks into a new “becoming” (a nod to the killer in Michael Mann’s 1986 film, Manhunter) expressed through nightmare imagery of body horror, insect swarms, and man-machine transformation.

In presenting the worst aspects of his most vulnerable self, Reznor’s music edges towards autobiography that would later manifest as a whirlwind of punishing self-reflection. Some listeners would see The Downward Spiral as a loose concept album about a man falling apart, not unlike Roger Waters’ self-loathing megalomania that fuelled Pink Floyd’s The Wall—another major influence on the album, although Reznor would offer no conclusive ending to his narrative.

At times, the bleakness of the album can seem overwhelming—a dizzying nihilistic tailspin. It was released before the Internet age of seeking listener approval, and Reznor did not set out to be liked or with a public image in mind, only for his music to be taken seriously. Flood and Alan Moulder both point to the need for taking creative risks without fear of hurting sales or upsetting the imagined listener, noting the triptych of “A Warm Place”, “Eraser,” and “Reptile” as their favorite songs—and proof that an experimental album could be both challenging and entertaining.

One of the most disturbing aspects of The Downward Spiral comes from the disembodied voices that cut across the songs. Alongside Reznor’s vocals we hear whispers, screams, and moans that complement his lyrics; often verging on the confessional, they are delivered through the persona of a nameless narrator. Reznor would often write his lyrics in isolation, only revealing them at the moment of recording, Flood says: “I would tend not to get involved in that part of the process, unless there was something I found objectionable.”

Reznor’s extreme approach was not without ironic controversy. Following the Columbine school shooting in 1999, the track “Big Man With A Gun,” Reznor’s forward-looking, satirical swipe against gangster rap, toxic masculinity, and American gun culture, would be implicated in discussions around youth violence (alongside future edgelord Marilyn Manson) and aggressive rock music at large.

While the album is considered a complete, holistic piece, Flood and Moulder suggest there might still be outtakes left in the NIN vault, with rumors of one track labeled “Rotation.” I asked about the controversial, mythic “lost” song “Just Do It,” which Flood apparently refused to work on. Moulder remembers it as a possible working title, but not as a final recorded track; partly due to its echoes of the Nike sneaker slogan. The Downward Spiral was the last Nine Inch Nails album Flood worked on—he remembers clashing with Reznor over suicidal ideation in some of his songs: “There were a couple of people we both knew who died by suicide; I think we both felt differently about that. There was a verse on ‘Mr. Self Destruct’ that I wasn’t happy with.”

The Downward Spiral offers a glimpse into a private abyss, where the listener is shocked out of complacency and forced to bear witness to the narrator’s descent. It was only later that the album would come to be seen as prophetic: By 2000 Reznor had slipped into longer depressive phases and full-blown drug and alcohol addiction, only to emerge from recovery in 2005 for the With Teeth album.

Seen in the cold light of Reznor’s new life, the aftermath of The Downward Spiral’s sudden success amid growing personal and creative struggle would continue to haunt him, until the closure of Nine Inch Nails’ 2013 album, Hesitation Marks. Continuing the collaborative spirit of The Downward Spiral, Moulder remembers recording Adrian Belew’s contribution on the later album: “He would be noodling or playing around, and we recorded track after track and then edited these parts together.”

With content that might now be considered triggering or “problematic” to contemporary listeners, The Downward Spiral’s raw expressions of rage and despair have, at times, proven cathartic and even therapeutic for those who feel alone in their emotional pain. For some listeners, The Downward Spiral offers a deeper resonance of individual struggles, embracing teen angst and going beyond the simple bait-love-and-desire of plastic chart pop.

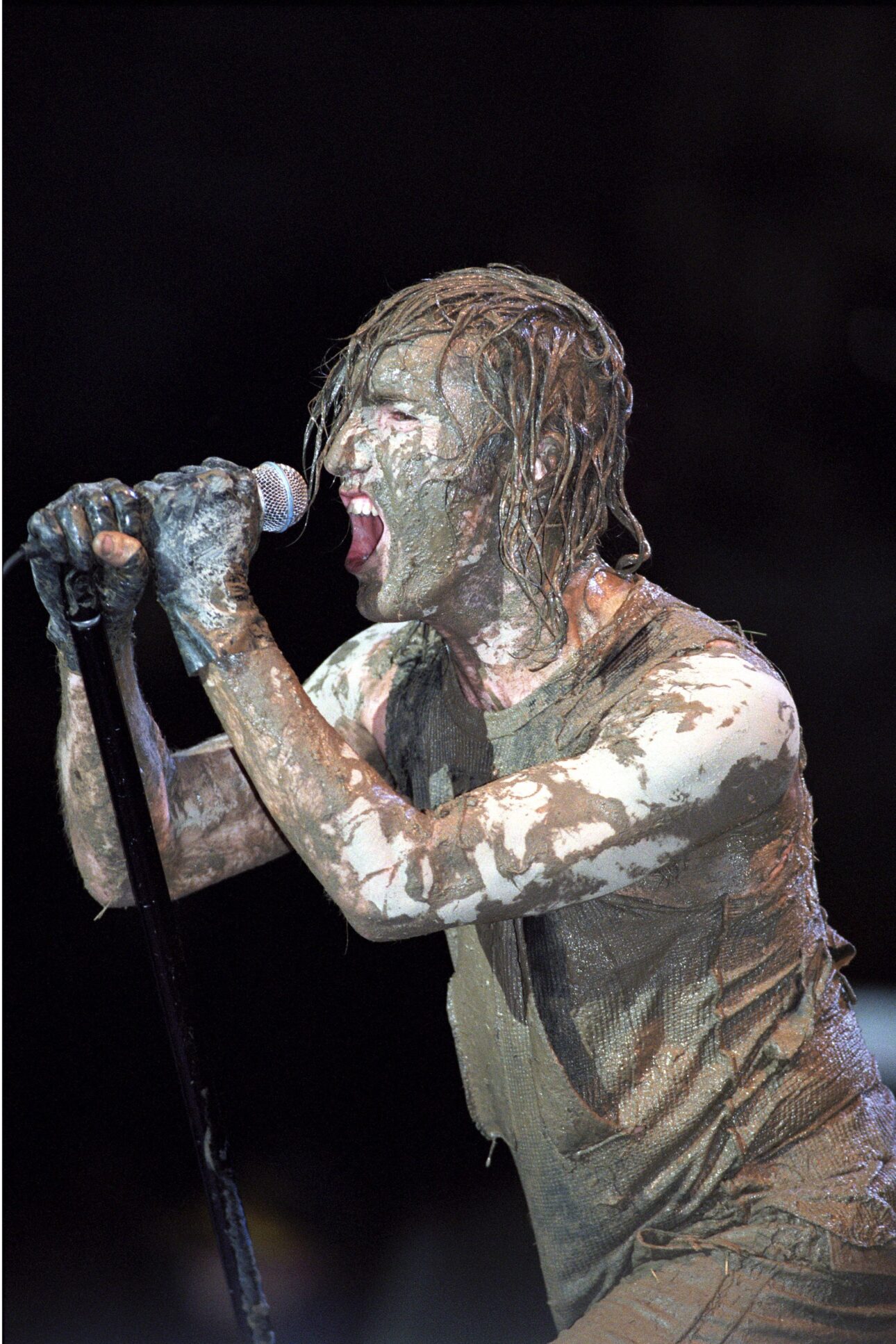

On release, The Downward Spiral defied expectations: going on to sell 5 million copies, launching Nine Inch Nails onto the extended year-long Self-Destruct Tour, and hitting a peak in popular consciousness with a headline slot at the relaunched Woodstock Festival in August 1994. Flood is keen to point out how hard Reznor worked from the earliest stages of his musical career, as he would later become embroiled in a difficult and protracted recording process for Downward Spiral’s follow-up, The Fragile: Hampered by false starts, and with Reznor mourning the death of his grandmother, as well as his beloved dog, Maisie, it was edited down from several discs of material into a double album and released in 1999, adding further momentum to Nine Inch Nails’ influence over the next generation of alternative music, particularly in the growing number of nu-metal and emo bands.

Moulder is still surprised at the runaway success of The Downward Spiral, given that it’s such a “dark, challenging” record.

“You forget how many great songs there are on there,” he says. “I had expected it to be critically acclaimed, but not so many record sales; perhaps it was the zeitgeist of the time.”