Karl Bartos is experiencing a renaissance of sorts in the 21st century—even though the prolific German musician has been actively releasing music for the last 50 years.

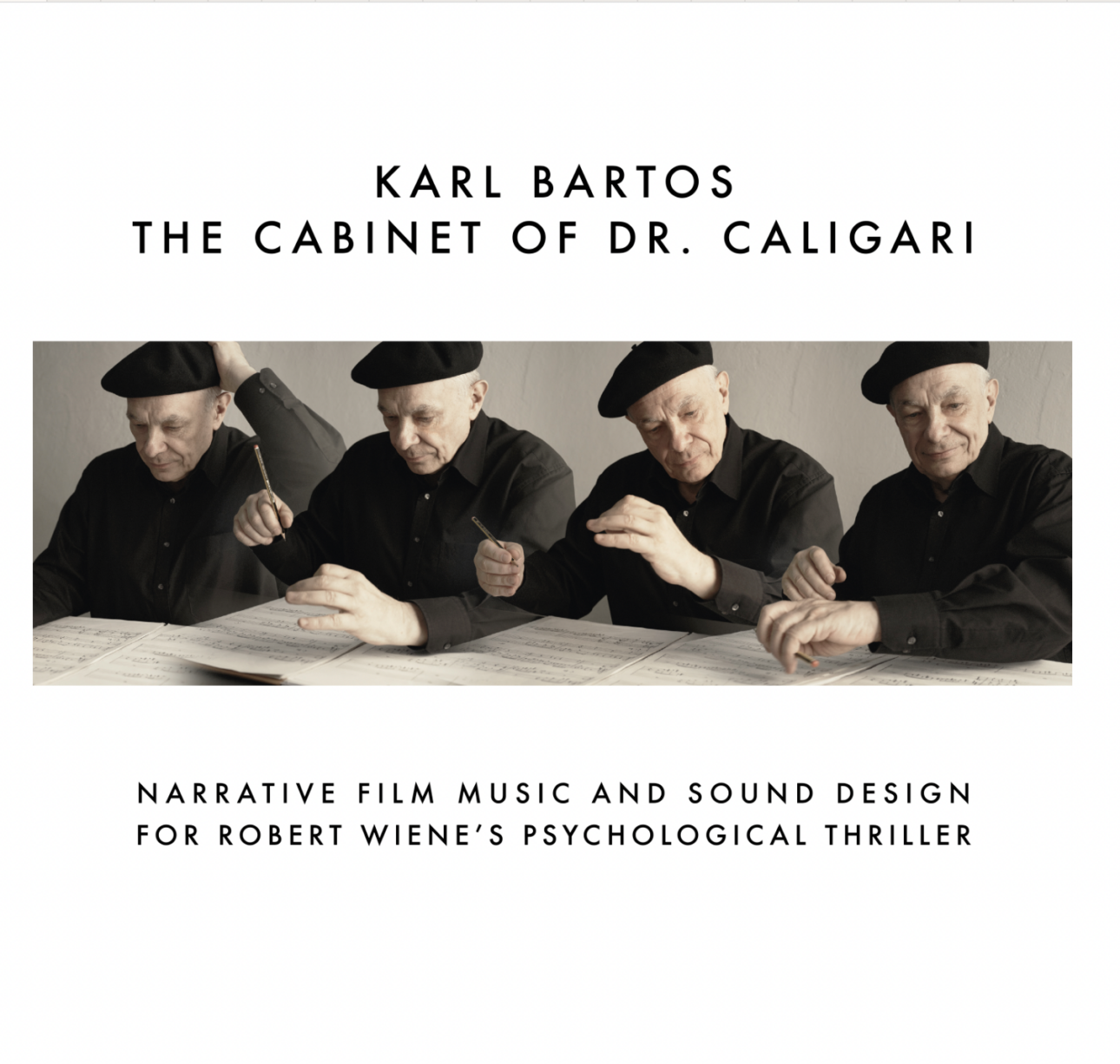

A member of the classic Kraftwerk lineup, Bartos was inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame in 2021. The English version of his autobiography, The Sound of the Machine: My Life in Kraftwerk and Beyond, was released in 2022, with the paperback released the following year. This month, Bartos’ brand new score for German filmmaker Robert Wiene’s psychological thriller The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari is premiering alongside the digitally restored 1920 film.

As vital and futuristic as the 71-year-old Bartos has always been, it’s the culture of 100 years ago, during Germany’s Weimar Republic era, that captured the visionary musician’s imagination early on in life. The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari is not the first time that Bartos has tapped into inspiration from the 1920s—Kraftwerk’s “Metropolis” was written after the group watched filmmaker Fritz Lang’s landmark science fiction film of the same name.

The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari is a standout film from that silent era. At first glance, it comes across as a classic thriller with an eerie aesthetic and exaggerated dramatics. Even the German text cards in between the footage are in spooky green, Halloween-esque font. But pay close attention to what’s happening on screen and there is a sly and markedly witty humor that underscores (pun intended) the film. Bartos responded to the film’s dichotomous nature, creating a soundtrack that elevates both aspects.

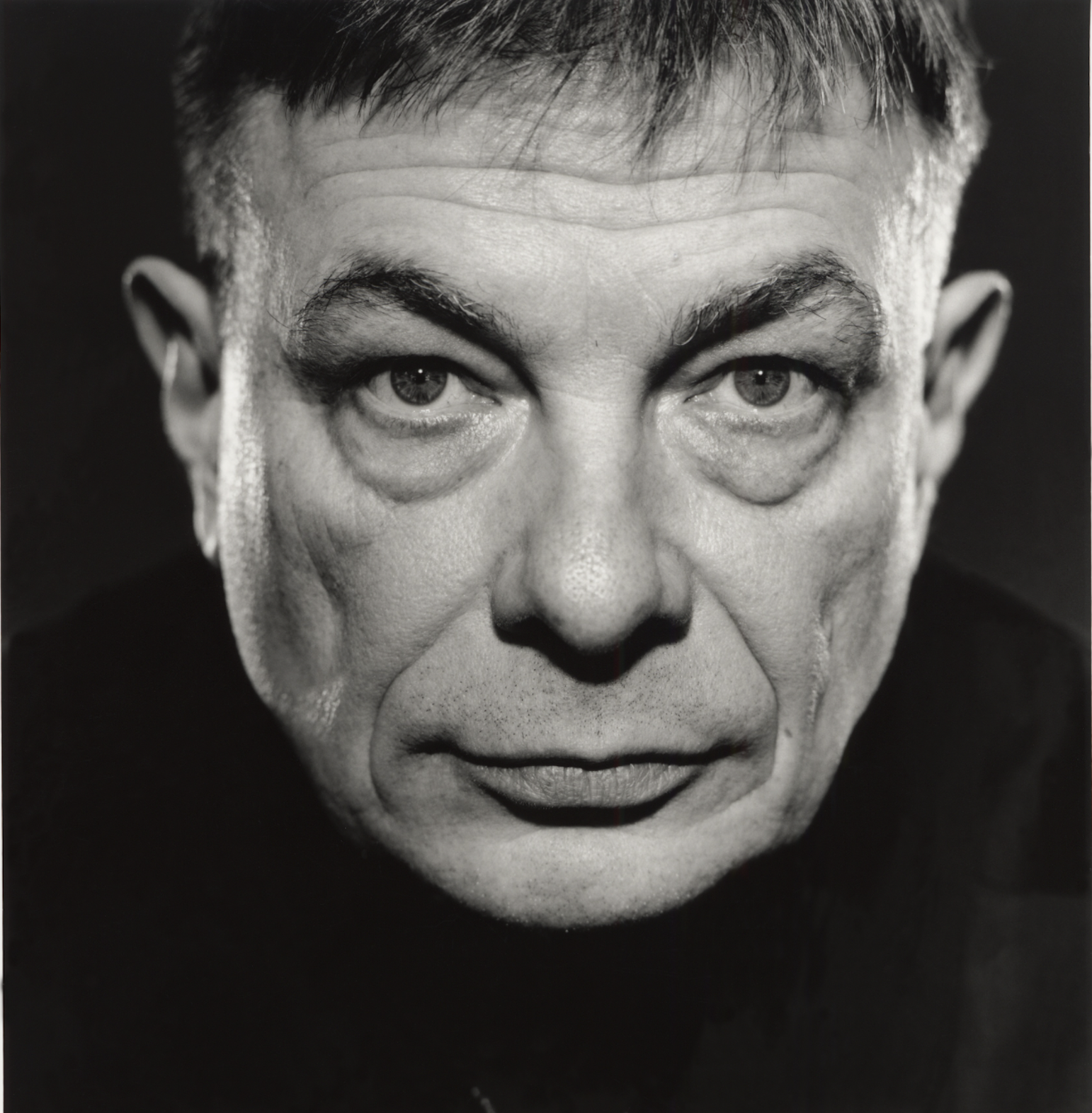

As he gears up for the soundtrack’s release, Bartos is quite excited. He sits in a room that is more office than studio, although a keyboard is propped on its side and a music stand looks lonely in the middle of the space. There is a poster of Bartos on one wall, but the real-life person is a lot more animated and smiley, keen to speak about his perfectly synced score that enhances the classic The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari.

SPIN: How did your fascination with the art and culture of the Weimar Republic begin?

KARL BARTOS: It’s a very important part of German history. The time between the First and Second World War, where everything went wrong in Germany, was a tragic period for people. But the arts were very fruitful at this time. The beginning of the 20th century was an explosion of art and progress. Before the film, we had so many machines being invented. The industry of killing was having tanks, airplanes, submarines, machine guns. They even had sound recording. Edison invented the phonograph in 1877. They had the telephone. But they couldn’t manage to bring sound and picture into one media.

For me, the question was, “How can I put silence into art, to close the gap to the film?” The trigger was when I was a member of my old band [Kraftwerk], we had this idea of the oscillating process between man and machine, to make that the center of our art. We came to Fritz Lang’s film Metropolis. We wrote the song “Metropolis.” We put the film into six minutes. I was really young then, in my early 20s, and I opened this door to the magic theatre of the Weimar Republic. I came across Caligari. I didn’t understand it at first. But all these characters are like robots with their overexaggerated movements. I’m fascinated by rhythm, and these people were living rhythms. I fell really in love and became addicted to this period.

Did you hear the original music from the film by Giuseppe Becce?

It’s lost. It was performed with the film, but it didn’t have original music. They ripped some parts from opera, from operetta, and from traditional music. They had a library of sad songs, happy pieces, all the feelings—they had a catalog, and they chose from that. Now, people do that with samples, and they will do it from artificial intelligence, probably. I was lucky that there was no original music. I had to come up with an idea by watching it silent.

When was the first time you saw the film?

Like with Metropolis, it was the second half of the ‘70s. We didn’t see the film. You couldn’t get tape. No internet, nothing. It was just pictures we looked at. I read this book by Lotte Eisner, The Haunted Screen: Expressionism in the German Cinema and the Influence of Max Reinhardt. She wrote, “The new media film combines the expressionist world view with psychoanalysis and the curious ghost world of romanticism.” At the time we also had [Düsseldorf and Duisburg-based opera company] Deutsche Oper am Rhein with operas by E.T.A. Hoffmann, romantic operas. This was the world where the Caligari is. It’s the product of the 20th century, but they put it 100 years earlier, and through a flashback, we’re in the 19th century and the 18th century.

How did the different time periods of the film influence the music you were creating for it?

The sound I composed for was a symphony orchestra, but it had to be transferred directly to electronic because you can’t copy a symphony orchestra. I copied it by synthesizer. A Clockwork Orange, Walter [Wendy] Carlos, he had this famous record in the ‘60s, Switched on Bach. When Kubrick heard it, he wanted to use this Beethoven track from the symphony, “Alle Menschen werden Brüder” or “All People Become Brothers,” as an ironic tool. When the main character was killing people, in his mind he was listening to “All People Become Brothers.” My soundtrack isn’t ironic at all, but I needed the orchestra sound.

The film was restored about 10 years ago, and is now digitally restored by the Friedrich-Wilhelm-Murnau Foundation. When did you start working on the score?

I started four years ago. It took a year to compose the basics. I did a lot of pre-syncing, which is very hard. There was no music, so I had to come up with a lot of the ideas for the compositions, inventing the parts.

How did it come about that you did this score?

It was my idea. Because, as I said, I fell in love with the movie so long ago. When I finished my autobiography, talking about Kraftwerk brought me back to the film, which was always on standby. I thought, “I should start now.” I talked to my friend Mathias [Black], the engineer. It’s really quite a task for two people. He is still in Düsseldorf. I’m in Hamburg. We got together every day through the computer. A technical brain and an abstract brain working together on this project.

How is it that this is the first film you’ve scored?

People ask me regularly to make film music. But the film composer is the last guy on the line. And someone always tells you how the music is supposed to be. I’m glad that I haven’t had to do it. This movie is so special. Everybody knows Metropolis, but Caligari isn’t that famous. Metropolis is a film about the future. You see a lot of machines. But the producers of Caligari were so clever, they put the film 100 years before the Romantic era so there are no machines at all. If you put a story into the future or the past, you separate it from the present. What you have is what people feel inside. Hundred years ago, people were like us. They had the same feelings and the same intelligence. Sometimes I think they’re much more intelligent than we are today having the education of the internet.

What were some of your key sound sources?

It has to be equivalent to these three time periods: 20th, 19th, 18th century. I had to have music which belongs to musical history. You have music from each period of the development of music, starting with the Baroque era where you have choral music, which could be composed by Bach, but I haven’t copied Bach. It starts before Bach, with Monteverdi. With Bach, they had this circle of fifths, and well-tempered tuning. It’s the idea of this time period. Also Prokofiev mixed with electronic music. Romanticism within music. I came to musique concrete.

I also thought, “What if I make the narrative world sound itself?” Like people walking. There was a journalist who visited where the film was made. He wrote there was a hell of a lot of noise. There was happy noise going on. I thought, “That’s my door. Why can’t I make the same atmosphere?” What you see in the narrative makes sound, even what people are saying. But I didn’t want to make it a talking movie. It’s just the idea of a madman who tells a story. I asked myself, “How do I perceive music and sound in my dreams?” I couldn’t remember. I have heard, all my life, music in dreams. But even working on the film for four years, I can’t remember a melody. But it’s not a normal dream—it’s a horror dream. I had this idea that people talk to each other, but it’s not real talking, it’s “emotion talk.” Sometimes they speak backwards. It’s not really what we do. It’s not communication. It’s musicalized talking. You can see the text in the film, which is the dialogue. But my talking is emotional or sometimes what I think is in their subconscious. A strange communication, a feeling communication. Every sound which is produced in the narrative, you can hear, which is quite a lot.

The music is explanatory in its tone, which helps if you’re not sure what’s happening in the film.

It’s adding another dimension, which is generating in your head. If you’re writing music for a ballet, for example, the choreographer creates choreography [for] it. For me, it was the opposite. I understood the movements and the edits like choreography. I composed the music to the movements.

The music sounds like my thoughts as I’m watching the film. It feels like I’m imagining the sounds.

This is exactly the intention. How can I put the viewer and listener into the narrative? Putting them not before the screen but into the screen. The screen is two-dimensional. I thought the third dimension could be created with the music. I made the film music and the Foley narrative sounds one concept. For example, the footsteps became part of the rhythm every now and then, not all the time. I had to produce them all, to see where I needed them and where I could fade them away. Same with the talking. It’s produced everywhere, but sometimes I go into the silent movie reception for short periods. It’s just a mashup of all these different thoughts I have.

Most people who compose for film think the music and the actions of the people in the film have to be consonant or dissonant. But my thought was, “How does the killing sound inside the killer? How does it feel? Maybe it’s a triumph for him, or a relief.” I started to make the film music more noisy or sometimes sweet. Maybe the devil is listening to a major chord instead of a minor chord and he’s happy with the major chord and a sweet melody. There’s a lot of ambiguity within music because it’s abstract.