Getting superstar musicians together in the studio is like herding cats. That’s a major takeaway from The Greatest Night in Pop, the documentary about the recording of “We Are the World,” one of the best-selling singles of all time. The film, directed by Bao Nguyen (Be Water), comes to Netflix 39 years and one day after the single was recorded in 1985.

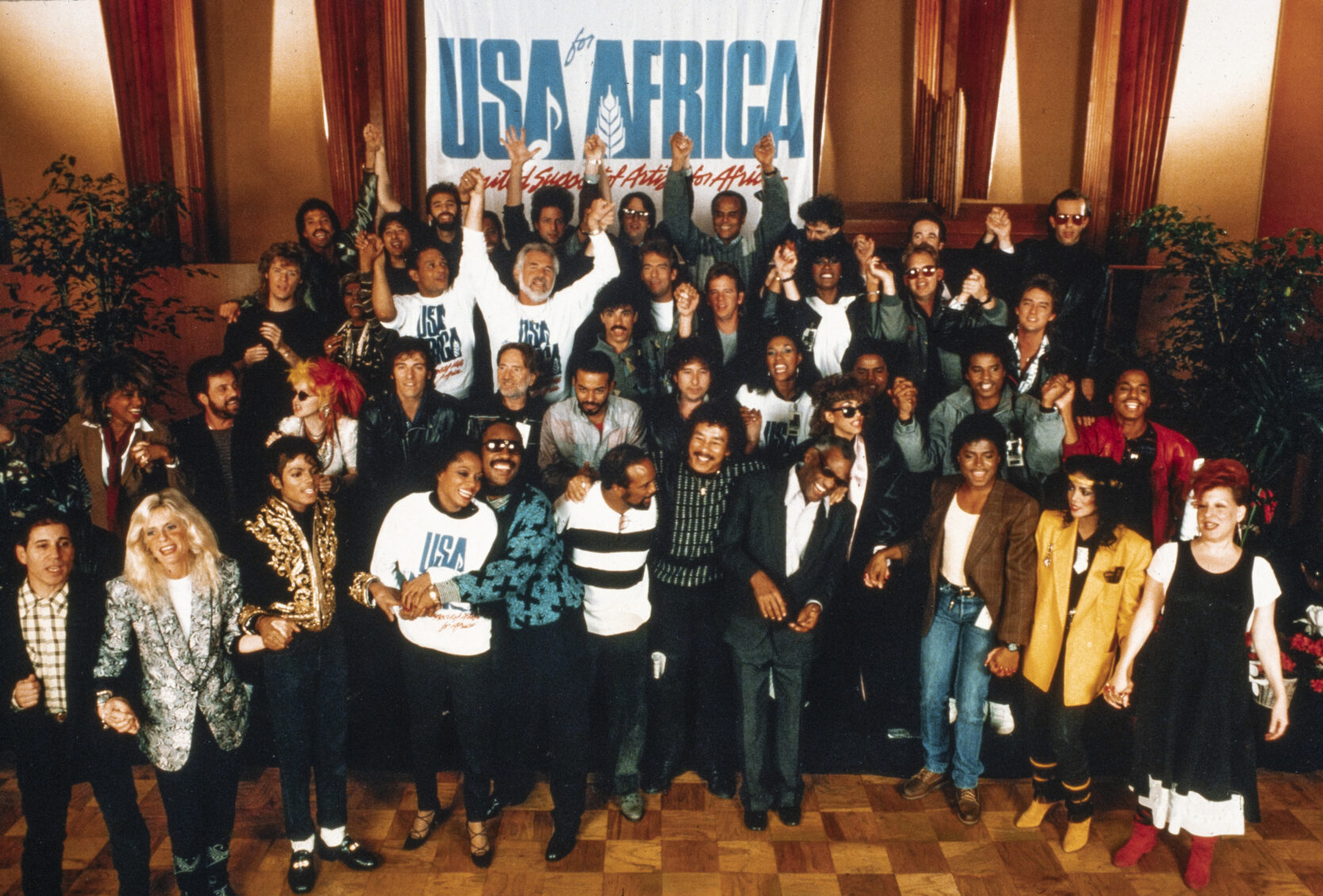

When the song was released on March 7, 1985, the accompanying video showed recording footage of the stars involved: Michael Jackson, Lionel Richie, Stevie Wonder, Bruce Springsteen, Cyndi Lauper, Diana Ross, Paul Simon, Kenny Rogers, Tina Turner, Billy Joel, Huey Lewis, Bob Dylan, and many others. As USA for Africa, under the production direction of Quincy Jones, they sang in turn, sharing the verses and the microphones, coming together for a worthy cause: providing food and aid to Africa, specifically Ethiopia.

The optics of this project have been excellent, not to mention the millions of dollars raised. The Greatest Night in Pop has a two-pronged effect. It triggers all the feelgood nostalgia vibes of a classic song sung by the most super of groups. It also blows up any rose-tinted images that may have existed about the song and the personalities (egos) involved.

The majority of The Greatest Night in Pop is extensive archival footage from that momentous night at A&M Studios (now Henson Studios). Also documented is the writing of “We Are the World” by Jackson and Richie at the former’s home. The development of the song is artistic genius—despite Jackson’s menagerie interfering and at times, frightening Richie. His anecdotes about Bubbles, Jackson’s famous chimp, his bird, and his snake are a hoot.

Additional period footage fleshes out the context of the time and the nascence of the idea, credited to Harry Belafonte and moved along by Richie’s manager at the time, Ken Kragen. After the release of Band Aid’s “Do They Know It’s Christmas” the month prior, Belafonte reached out to his famous friends saying, “We have White folks saving Black folks. We don’t have Black folks saving Black folks. That’s a problem.” Still, Bob Geldof, the organizer of Band Aid was on hand in the studio and gave the pre-recording pep talk that put the project in perspective for the artists and brought gravity to the scene.

The artists were chosen based on who would sell records. The demo was sent around on cassette tape four days before going into the studio. Two days before recording, the song’s arrangement was done, as was the physical arrangement of the artists around the room. The song was recorded the same evening as the American Music Awards, after the ceremony, as many of the artists would be in town, and, provided they didn’t go to any afterparties, available.

Conspicuously absent is Madonna, but it’s revealed that Kragen wanted Lauper. The implication is that it’s one or the other. Ironically, Lauper almost didn’t come because her boyfriend heard the demo and didn’t think it was a hit. Also missing is Prince. In fact, many minutes of the film are spent talking about the ongoing schemes to get him into the room. Sheila E. goes as far as to say she was asked to sing so she could be used as a carrot to entice Prince to join the recording.

Current-day talking heads Richie, Springsteen, Lauper, Dionne Warwick, Kenny Loggins, Smokey Robinson, and Sheila E. bring an insightful perspective to the experience. Also filling out the pictures are the audio engineer, lighting designer, and videographer. This narration brings a lot to the priceless original footage. Loggins says there was a “low hum of competition…the egos were still there.” At one point Stevie Wonder helps Ray Charles to the bathroom and the observation is: “The blind really leading the blind.”

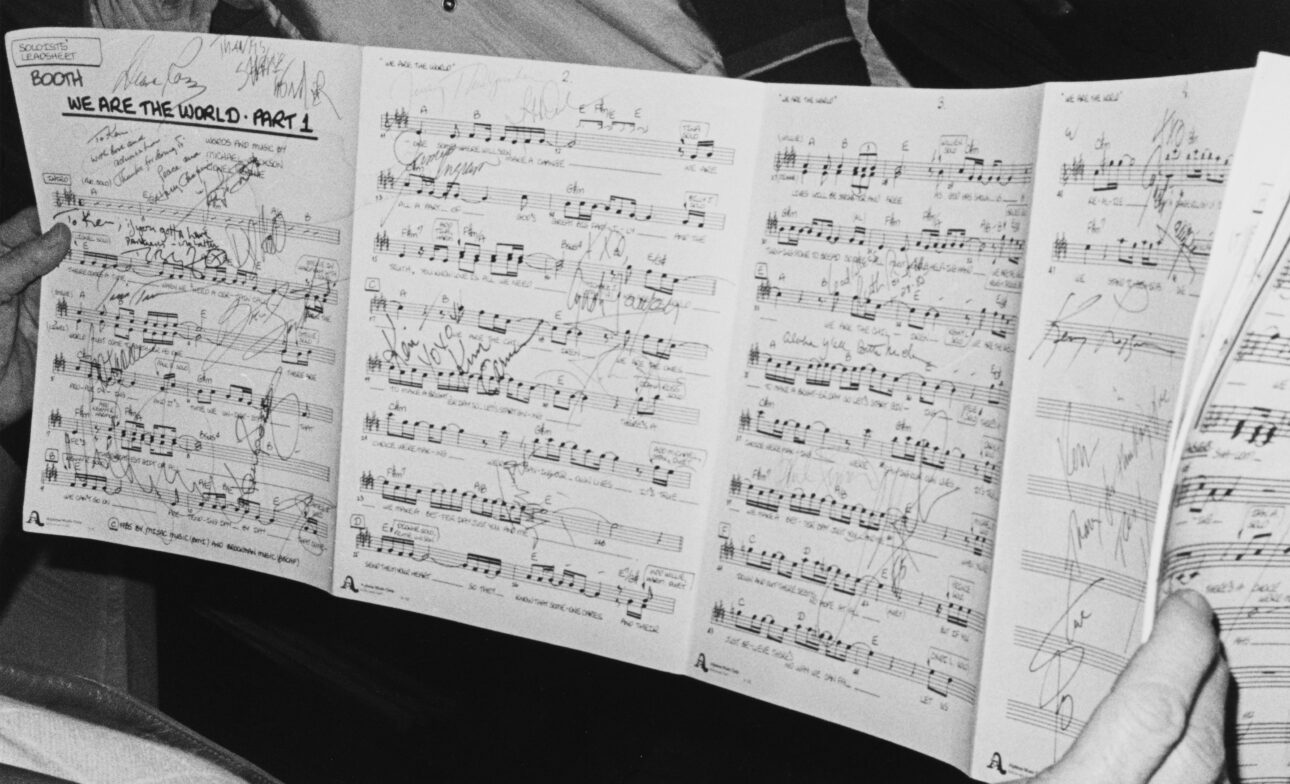

That the stars are in awe of each other is tangible and as Lewis says, “We got to interact with each other and that was the thrill.” Ross broke through this invisible wall when she asked Daryl Hall to autograph her music sheet, which sparked everyone else to do the same. The image that is the most indelible is Bob Dylan looking absolutely terrified, painfully uncomfortable, and about as far out of his element as he can get.

After a whirlwind week at Sundance where The Greatest Night in Pop premiered, Nguyen joins SPIN to talk about his presentation of that historic night and how he struck the balance between sentiment and humor.

How did you come to this project?

Mid-2020, we were looking for projects that had archival footage because we didn’t know when we could shoot anything. Through her development team, my producer Julia Nottingham found the story. She knew the song, but she had no idea about the story of how it happened in one night. We decided it was very compelling.

I was only two years old when “We Are the World” came out. I don’t remember the huge impact of the song. But my parents, who were Vietnamese refugees, had just come over to America. They didn’t speak a lot of English, but they had Lionel Richie albums, Kenny Rogers albums, and they were always playing “We Are the World.” I had personal connections to it, but I wasn’t sure if I was the right person to tell the story.

It was a trip to Vietnam shortly thereafter (my parents have since moved back) when I got into a taxicab and the 60- or 70-year-old Vietnamese driver, who spoke no English, put in a mix CD and the first song was “We Are the World.” I thought that was serendipitous and it made me want to explore why the song was so important to people, but also to find out about making of the song, an impossible feat in many ways.

How did you get started on the making of the film?

I don’t make music documentaries. We didn’t have connections to Lionel Richie or Michael Jackson’s estate, and we didn’t know where to start. But Julia happened to be working on a project with MRC, who used to own Dick Clark Productions, who produced the American Music Awards, which we knew was an entry point into that world. MRC told us we should contact Larry Klein who’s in the film. Julia cold-called him and gave him the elevator pitch. He said, “I’ve been waiting for this call for 35 years.” Again, serendipity. We asked, “Has anyone approached Lionel?” He said, “A lot of people have approached him, but he hasn’t found the right team.” Julia had the tenacity to pursue it. With my vision and my connection, he gave us the keys to the kingdom.

Where was all this amazing original footage?

USA for Africa owns the footage. The footage was all over the place because they made the recording for a music video and TV special as part of the release of the song and music video. They didn’t think that almost 40 years later, filmmakers would approach them to make a documentary. The footage was in boxes and car trunks and some of it was really damaged from moisture. We had to bake a lot of the tapes to revive it. Now, since it’s such a historical document, it’s in the Smithsonian.

There is footage from the writing of the song and Ken Kragen’s office, as well as Los Angeles from that period that really complements the video of the recording. Where were those from?

One of the other discoveries of this film through our amazing archival producers was the David Breskin tapes. He was a journalist who was covering the event for Life Magazine. As soon as he got the assignment, he turned on his dictaphone and recorded every conversation he had from three weeks before the recording, as well as the recording. As I mentioned before, a lot of the archival was not in the best shape, and a lot of it was missing audio. They were recording the audio into the feed of the sound board, so it was only when they were recording the song that we heard any audio. A lot of those conversations you hear in the film are David Breskin’s tapes. We had to eye match that audio to what we’re seeing from the archival. It created this rich texture and immersion into the story that we didn’t have before.

Ken’s office and MJ [Michael Jackson], a lot of that audio was from Breskin’s tapes. But me playing director, we recreated a lot of those scenes and what you’re seeing is my vision of what happened based on those audio tapes. I was adamant about getting the exact same cameras that were shooting the recording studio. For me, it’s about immersing the audience in the full experience, story, characters and emotion. All we had was audio, but how do we bring you into this world of Ken and MJ and Lionel writing – and Quincy? The combination of what we shot on our own in modern day and found archival films of Quincy and Michael, we seamlessly put it together to feel like one cohesive film.

You made the stylistic choice of keeping the entire film in 4:3 aspect ratio, including the modern-day talking heads parts, which is very effective in keeping the visual thread.

When I’m watching a film, I personally don’t love talking heads, especially when you’re talking about something in the past. You’re jolted into a different time and a different world. I felt for this film, it was important to see the interviews because our participants are so dynamic, so iconic and they tell the story so well. We wanted them to tell it so it felt like it was in the present tense. That was one way to keep the viewers immersed in the story and not think of it like a retrospective or looking back.

Stylistically, the whole film is a practice in nostalgia. Most of the interviews were shot at Henson Studios, which was A&M Studios, in the room where it happened. It was important to me to capture that spirit and the energy of that room. A lot of the people that we interviewed hadn’t stepped in that room since the night of the recording. When they came back into that room, other memories rushed back to them. That’s another reason why we show the interviews. I don’t want to spoil it, but at the end it all makes sense of why we’re in that room.

How did your background in editing come to play in how the film comes across?

We had amazing editors. My background in visual storytelling, I wanted to make sure you felt like you were riding along with Breskin or Lionel Richie. You’re traveling through the streets of LA. You’re in Venice. You’re in Hollywood at night. You’re seeing these characters. Every shot was intentional to make sure it all blended in, and viewers were on this journey, driving through 1980s Los Angeles. It’s very much a love letter to LA as well.