Houses of the Holy is on the turntable, but it’s “The Blue Danube” that is coming out of the stereo.

“I only listen to classical music on the radio, all the time,” says Zander Schloss, chopping some anchovies into paste for a salad dressing in his makeshift kitchen, downstairs in the back of a house in Los Angeles’ hilly Silver Lake neighborhood.

A tri-tip steak sizzles in a cast-iron pan on an induction burner. A painted portrait of his mother, who died last summer, made when she was young, looks on from the opposite wall of the room. A few guitars and a small recording set-up line the room, where he crafts some of the most delicate, moving, melancholically poetic songs you can imagine.

It’s been a bit of a rough year. Not only did he lose his mom, but also some key figures in his art life. Just the week before, singer-guitarist Mike Martt, with whom Schloss partnered in the ‘80s and ‘90s L.A. band Thelonious Monster and then in the folk-romp ensemble the Low and Sweet Orchestra, had died. And two days later, the world lost Shane MacGowan of the Pogues, whom Schloss got close to when they both were acting in Alex Cox’s 1987 movie Straight to Hell.

“Think about James Fearnley,” he says of the musician who was in both the Pogues and Low and Sweet. “He lost two singers in two bands that he played with.”

But Schloss had others to grieve as well.

“I’ve lost Dix Denney this year, from the Weirdos,” he says. The two of them both played guitar in the early L.A. punk band’s 1990s revival and roomed together on the road. “And [last year, Dead Kennedys drummer] D.H. Peligro, who was from St. Louis, my hometown. Right? You know?”

He pauses.

“You want some salad?” he offers to his guests, me and my wife Susan, who have been friends with the musician for many years.

He takes in the chilled air on the covered patio outside of his place, where he’s serving dinner.

“I had a friend say, ‘Yeah, this is around the age that we start losing people,” says Schloss, 62. “I said, ‘You’re wrong. It’s more like 70s and 80s. But in the punk rock community it’s in the 60s ‘cause of the rough living we all did.’ And I swear to God, I wanna talk to some of my peers. I think to myself, ‘Did we get hit with Agent Orange or something like that? What happened to us? Either we’re dead, or we’re living in our grandma’s basement, or we had to get sober, you know?

“So, you want some mashed potatoes?”

Amid all this mortality, Schloss has been furiously active with his music, in two different shapes. Very different.

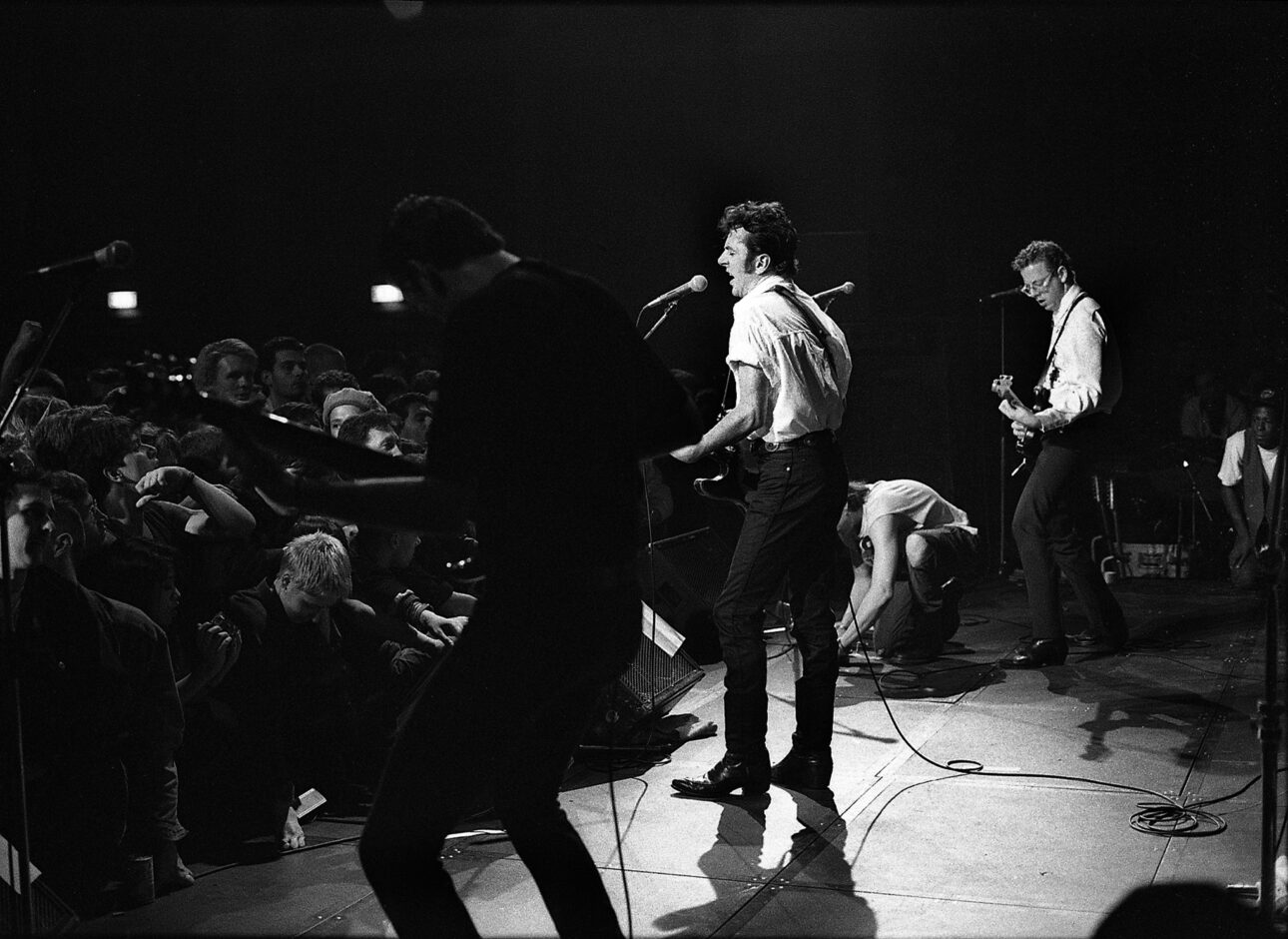

On one side, in the summer and fall he was on the road as bassist with foundational L.A. punk band the Circle Jerks, playing festivals and amphitheaters for thousands of moshing fans, young and old, a night. When the group heads back on the road in early March in a double-bill tour with the Descendents, it will be 40 years since he joined the Jerks, which still also features founding singer Keith Morris and guitarist Greg Hetson.

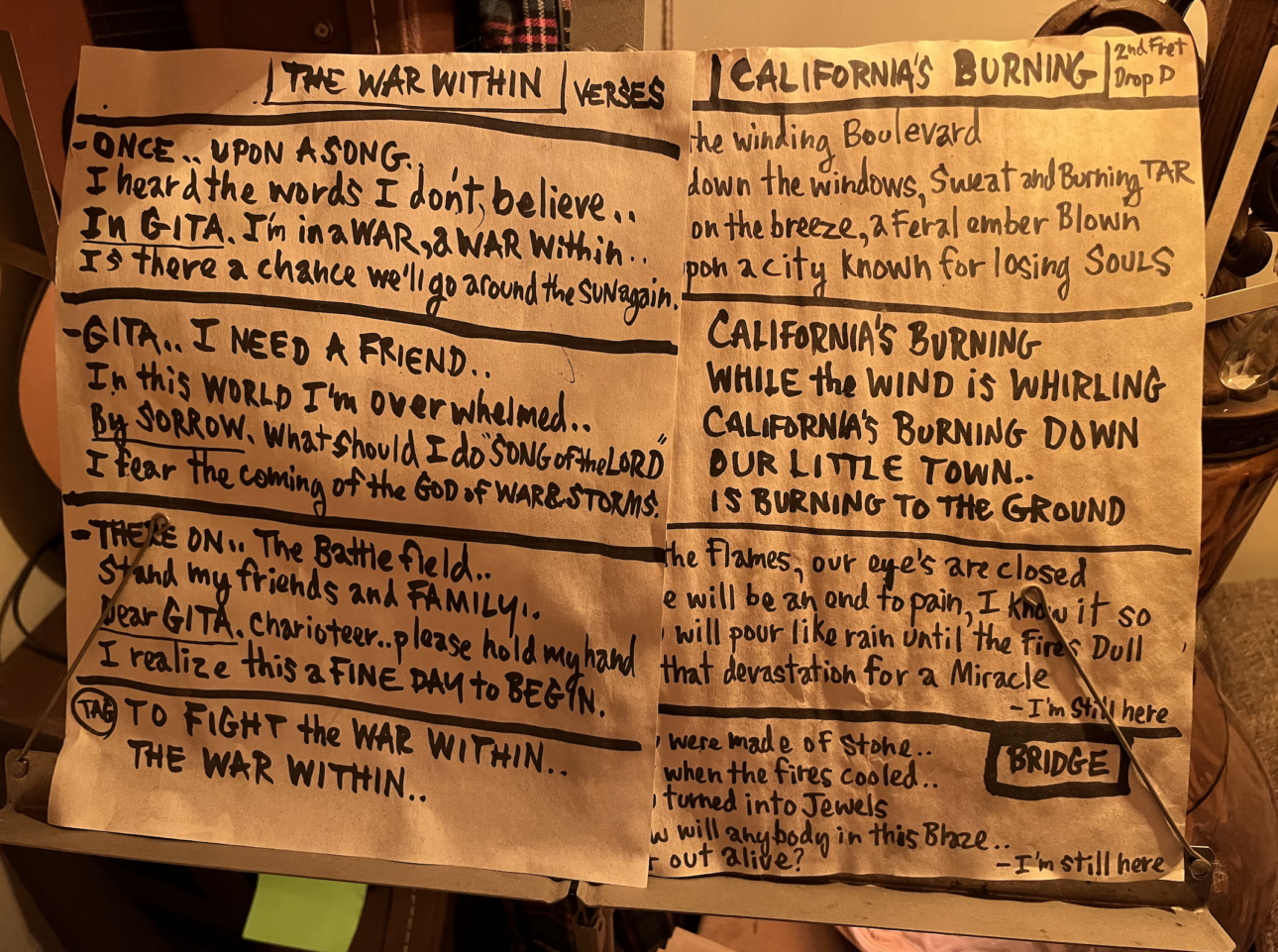

On the other is his own music, as showcased on 2022 album Song About Songs and the brand-new Californias Burning. The latter was produced with sympathetic touches by Alain Johannes (Queens of the Stone Age, PJ Harvey), and on several songs with strings and other orchestral touches written and arranged by Schloss himself. This is heartfelt balladry spotlighting his almost lute-like virtuosity on guitar (both 6- and 12-string) and bouzouki (delicate, fragile, nothing Zorba-esque) and his mix of melancholy and introspection embodied in his earthy singing. He’s the 21st century answer to John Dowland, Queen Elizabeth I’s famously dolorous court musician.

Led Zep vs. Strauss? That’s nothing next to the Schloss Dichotomy.

“It’s a process,” he says of finding his own voice in his music, getting in touch with his, well, feelings. “And I’ve been on it for a long time. And I like it.”

Through years of punk aggression and heavy drug use, though, he shut a lot of that off in himself. He’s 18 years clean now, active in the L.A. sober community helping others find and keep their way out of all that. And he’s conscious of how it’s changed him.

“I don’t think I’m supposed to feel good all the time anymore,” he says. “I did when I was copping heroin every day, you know. I knew how I was gonna feel. I knew what I had to do. But that’s the coward’s way. This is a hero’s way. If I am the hero, I’m just trying to find my way home at this point, Ulysses’ Odyssey, so to speak. It’s like I’ve crashed into the bluffs, I’ve wrecked the ship, and I’ve battled the Cyclops and, you know, succumbed to the sirens—and all that there is for a man to do in his life. [Now] I’m not looking to take over the whole world and conquer. I’m just trying to find my most authentic place and find a home in myself. I think my music reflects it. So that’s me. If you love that music, you love me. And I’m always looking for love, because I need more than the average guy.”

And that, in fact, is where his music story begins, more or less. In his youth he was an aspiring artist, preceded by three generations of painters on his father’s side. In his teens in the San Diego area, where he’d moved at 13 after his parents’ divorce to live with his mom and her boyfriend, he had an adolescent epiphany.

“I thought to myself, ‘Jesus, how am I gonna meet a girl sitting back here in my little art studio?’” he says. A book of Bob Dylan’s drawings and poems, though, sparked a different idea.

“I was like, ‘If I start playing guitar and start bringing the guitar to school, if I learn the song “Landslide,” I can ask the prettiest girl at school if she knows the words, and that will bring me closer.’ And I did that many times.”

His tastes leaned to singer songwriters at that point: Leonard Cohen, Neil Young, Dylan, of course. And yeah, Zep too.

“But when I wanted to make my own choice of who I wanted to be, it was the troubadour,” he says. “Because there was a direct line from the solo troubadour to me. I could hear the lyrics. I could hear the chords. I’ve heard a lot of people in punk rock say, ‘I heard this punk rock band. If they can do it, I can do it.’ And that’s how punk was born.”

He reaches for the mashed potatoes.

“But how I was born was listening to the guys strumming on the guitar, singing a melody and some words. Plus the message was very clear. And I was going through terrible times with family dysfunction and divorce and an alcoholic dad. The same old story. I don’t want to get into it, but I was a sad boy. I’ve always been a sad and lonely person. And so the music was a way for me to self-soothe. Music was a way to find therapy. It was also a way for me, so I thought, to find the validation of my parents, which I never got. My mom was not one to say, ‘I’m proud of you.’ And my father never said any of that to me. But it’s like, wha wha wha, here I am. It’s made me the beautiful person that I am today. And I realize all that pain, all that tragedy, all that trauma, makes us who we are. And who we are has to be okay. Because there are no take-backs. I didn’t turn out so bad. Despite all of my terrible modeling, I’m proud of myself.”

It took him a while to get here. While still in high school he drifted to jazz guitar, and after graduating at 17 lived for a year with his jazz teacher, painting houses to make some cash. After that he moved to L.A., enrolling at the Guitar Institute of Technology, taking on a series of short-lived jobs—making popcorn at the historic Chinese Theatre, selling Christmas trees for a firm owned by Jehovah’s Witnesses.

“I became a Jehovah’s Witness for a week, but when I came in for my paycheck, they shorted me,” he says. “And I was no longer a Jehovah’s Witness.”

Not too long after, he found himself in the world of hardcore punk, with its own mix of excitement and dysfunction, and, for him and others, hardcore drugs.

“What a weird cast of characters to be thrust into,” he says. “I was cast into that group of misfits, lovable misfits.”

He considers the years.

“If you would’ve said to me back then that you had a premonition, ‘When you are 62 years old you will be in one of the most important seminal punk rock bands in the history of hardcore punk rock and you will be touring the world and selling out giant venues and highly successful at what you do,’ I’d say, ‘You’re crazy,’” he says. “I would’ve said, ‘Look, we’re a bunch of outsiders. We can’t even get a gig at a proper venue. Nobody will put out our records. It’s a fad. It’s a phase.’ And so therefore I didn’t really pay attention. I didn’t think about it. It was just like, ‘Hey, I’m having fun. It’s sex, drugs, and rock ‘n roll. I’m just going with it.’”

Through the punk scene he was recruited along with other cohorts into writer-director Cox’s grassroots film world, first co-starring with Emilio Estevez and Harry Dean Stanton in the wonderfully weird Repo Man, in which he plays uber-nerd Kevin, a proto-Napoleon Dynamite who is the best friend of Estevez’s Otto. After that was Straight to Hell, a mess of a film, but a place where he befriended musicians who helped him get back in touch to his folkier roots, notably members of the Pogues and Joe Strummer.

In the ‘90s he was part of Thelonious Monster, a band with great potential but greater issues with drugs and personality clashes, fronted by Bob Forrest, who went on to success as a noted celebrity drug counselor. That led to the Sweet and Low Orchestra, a step back closer to his pre-punk roots, as well as work with Scott Weiland, Mike Watt, various soundtrack projects and, after an early-‘90s hiatus, continued semi-regular touring with the Circle Jerks.

Having gotten sober, in 2007 he formed a duo with punk-rooted singer-songwriter Sean Wheeler, from the California desert punk band Throw Rag. The two embraced their acoustic, sensitive sides with such songs as “Catch Me If I Fall,” “Sometimes We Try,” and “Song About Songs” (though also “Good Pussy”).

“Song About Songs,” a hymn of salvation through music, later became the title song of Schloss’ first real album (not counting 2017’s Dear Blue, which was only sold at shows). The real heart of the album, beautifully produced by Gus Seyffert (Beck, Bedouine, Roger Waters), is Schloss’ own serenity prayer, “I Have Loved the Story of My Life.”

For the new album, Schloss turned to Johannes, whom he knew through the L.A. scene. He’d greatly admired Johannes’ work producing Mark Lanegan (for whom Wheeler and Schloss had opened on tour) and playing with PJ Harvey, Queens of the Stone Age, Chris Cornell, Them Crooked Vultures (with Dave Grohl, Josh Homme and Led Zep’s John Paul Jones), and in his own cherished band Eleven, the latter with his wife Natasha Shneider, who died in 2008. So much was his admiration that he was intimidated when they started recording, but he says that Johannes proved greatly supportive and helped build his confidence.

That confidence led Schloss to take on something he only imagined doing before: adding sessions for several songs in which the core band was joined by a string quartet, woodwinds, including flute. He’s giddy talking about it.

“I’ve got that kind of cynicism that an old man has,” he says. “But I’ve also got that kind of childlike wonder and optimism of a kid who doesn’t know any better. He might be crazy, he might be stupid, he might just be innocent. Or maybe he’s a dreamer.”

One night a few months ago, Schloss took the stage at the club Venice West near the Pacific Ocean. To say the audience was sparse understates it. There were perhaps 10 people there, several of whom were merely having a drink and left as the music started. The waiter was sent home early as there was no food being ordered and few beverages.

Schloss made note of this from the stage, but good-naturedly. It did not impact the performance. Accompanied by bassist Brandon Rauch and drummer Beth Goodfellow, Schloss’ guitar and bouzouki playing was even more mind-blowing and dynamic, his voice even earthier, more expressive than on the records.

“It was great,” he said, shaking off the low attendance of the night. “I mean, well, a guy named Joe Strummer said to me while we were playing together, ‘It’s a privilege to play for an audience, whatever size it is.’”

That’s not just a glib line. It left a great impression on Schloss, as did much of the experience when the two collaborated on music, including the score for Walker and Strummer’s post-Clash album Earthquake Weather and then in Strummer’s band, with Schloss playing guitar and serving as musical director.

“That guy taught me a lot about being a gentleman of rock ‘n roll and having gratitude.” he says. “Think of how he felt with the Clash, one of the most important rock bands of [the ‘70s] and him basically being responsible for fucking breaking it up. He was quite humbled when I was playing with him. And quite available to people. We’re both Leos and a little bit cut from the same cloth.”

He lets loose a laugh, an affably eruptive guffaw that punctuates his conversation regularly, serving both as emphasis and an amiable shrug.

“We spent hours and hours talking and commiserating about life and philosophy and music. We both had that kind of cynicism, but still that wonder about everything and everybody—social stuff, poetry, music, geography, whatever. And so he taught me that. ‘Just don’t be a dick and be ungrateful and get up there because there’s only five people in there. You’re doing this. It’s a gift that you’re giving people, no matter how many people are in there. And these are your friends.’ You know?”

And whatever the numbers for his solo shows, it’s a gratifying change of pace.

“For the first time I’m not getting punches on the arms from big sweaty dudes going, ‘Bro, do you do hugs? Can I take a selfie with you?’ And it’s like they put their arms around me assuming that they can touch me. I’m like, ‘No, that’s gonna cost you five dollars extra to touch me.’”

He laughs again.

“But there are women that are coming up to me and saying, ‘Oh my god, your music is so beautiful. It touched my heart.’ And it proves my point that females, with their feminine energy, which is a nurturing energy, which is a healing energy, respond to this. And I’m not afraid to say that I have that feminine energy and that attracts females, because it’s romantic, it’s honest. It’s a feeling. And I know that I’m on the right track when women keep coming up to me. Not dudes. No dudes responding to this music.”

Tonight, Schloss is not only mourning friends, but also a nearby restaurant that has just closed, a Cuban cafe that was a local anchor. In his bedroom there’s a large black and white picture, about a-foot-and-a-half tall and a yard wide, of the view from the corner outside the cafe looking east on Sunset Boulevard. It looks like a photo, but it’s actually a painting he commissioned from a friend.

“That was my view many days, sitting there,” he says.

When news spread about the closing, a number of social media comments noted the restaurant’s back room, which for years hosted 12-step meetings. Various people said that those meetings, that room, saved lives.

“It saved mine,” Schloss says. “That’s why I had my friend do the painting.”

He deeply values the community of sobriety, as well as the community of music.

On that note, the opening song on Californias Burning is titled “I’ll Be Your Friend.” If that sounds a bit Fred Rogers-esque, keep in mind that Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood was not all smiles and sunshine and cardigans, that it was a place where complicated emotions and experiences were brought out in the open, a place where being a friend and having friends really mattered in coping with all of that. Same for Mister Schloss’ Neighborhood.

Here there’s the muted “Memories of Me and You,” the hoping-beyond-hope “100 Years,” the somber “All the Bells Are Ringing,” and the ashes-filled title song:

Our little town

Is burning to the ground

“There are a lot of layers to it, and there’s a shitload of melancholy to it,” he says.

Of course, there’s also “Play Me a Happy Song,” with a snappy beat and cheery melody. Don’t be fooled, though, he warns. Not that he gives us a chance to be fooled.

“That’s a result of my manager Tom [Carolan] saying, ‘Why do you always have to play slow, sad songs?’”

He laughs. After all, one of the songs on his last album was titled “Married to Sadness.”

“So I wrote a song about him saying, ‘Play me a happy song,’ and sort of counted some of the reasons why I think it’s not a realistic thing. Like, ‘Why do I have to act like I’m okay for you to feel comfortable?’”

He quotes a line from the song:

I gave up on humanity

Don’t worry, I’ll be okay

It’s better this way

“Everybody’s terrified, right?” he says. “And nobody’s talking about it. They’re just sitting there with their arms crossed, going, ‘Everything is fantastic’ and being tough guys. I can clearly see the toughness is killing the world. And it’s my crusade to be the anti-tough guy. It’s actually braver to be tender. Braver to be honest. Maybe we can all get together and—I don’t mean to sound like a pussy—expose our transparency and vulnerability and have a good cry together about how fucked up things are. And maybe people could be a little bit more compassionate towards one another and generous.”

With that he gestures to the spread on the table, now cold, and ponders just one more mystery of the universe.

“I feel like the beef was a little tough,” he says, chewing. “I’m wondering if it’s the cut of meat or the way I cooked it. I don’t know. I don’t think we’ll ever get to the bottom of that question.”