Four women stride on stage. Fists clenched at their sides, chanting in Russian, in rhythm, words from Riot Days, the book by Maria “Masha” Alyokhina. Masha is one of three members of Pussy Riot sent to prison for two years in 2012. A decade on, the Pussy Riot Russian feminist protest art collective has grown, and here at the Bottom Lounge in Chicago on November 6th for their Riot Days tour, they spread the message: “WE WON’T DISAPPEAR.”

Pussy Riot formed in 2011 in response to Vladimir Putin “winning” a third presidential term in an election widely condemned as rigged. Members had been involved in performance art collectives prior, but Putin’s power grab sparked their urgency to warn the world.

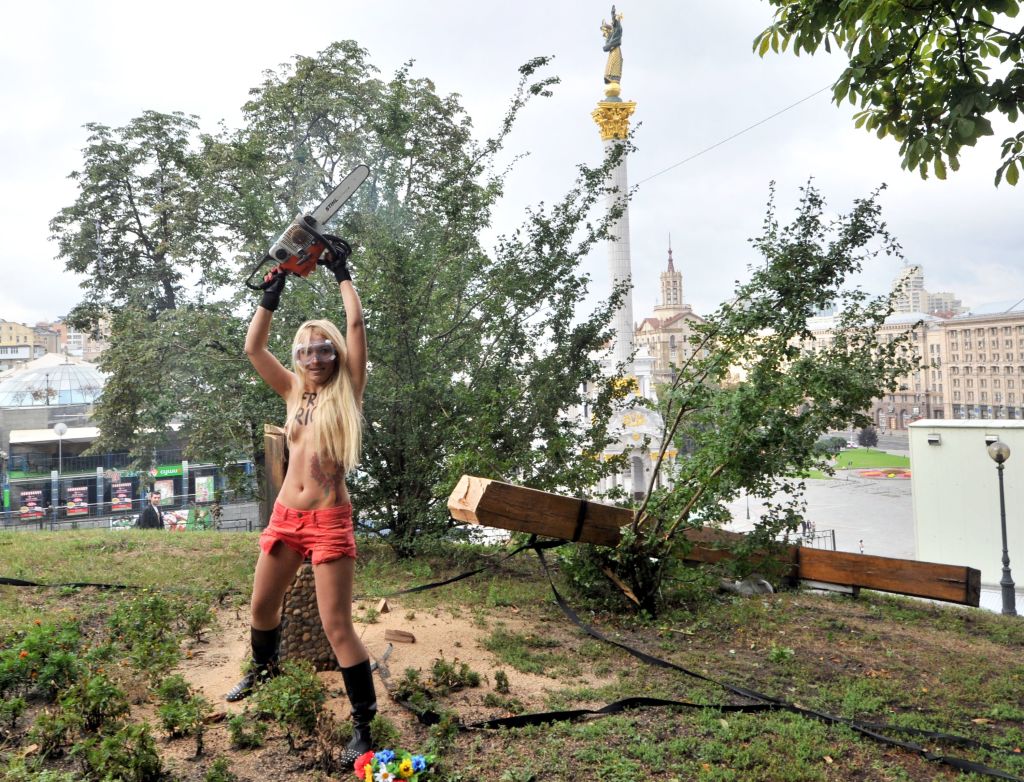

The world definitely noticed “Putin Has Pissed Himself,” Pussy Riot’s punk show performed in Moscow’s Red Square in January 2012, clad in neon balaclavas. Their subsequent protest, “Punk Prayer,” a 40-second disruption inside Moscow’s Cathedral of Christ the Savior in February 2012 sought to expose Putin’s embrace of the Russian Orthodox church and its Patriarch Kirill to solidify his regime. For their “hooliganism,” Pussy Riot members Maria Alyokhina, Yekaterina “Kat” Samutsevich, and Nadezhda “Nadya” Tolokonnikova served two grueling years in penal colonies.

This is the subject of the Riot Days tour — and it’s a cautionary tale.

Also Read

KEEPING IT REAL — ROUND TWO!

“I warned the world that he will do more,” says Masha, “and there will be more blood. Now it’s not an authoritarian regime. It’s a terrorist state. I’ve seen how it works from the inside.”

Pussy Riot members prophesied Putin becoming a dictator. They witnessed his seizure of Crimea in blatant violation of international law, the war in Ukraine, the war crimes in Bucha, the mass abduction of Ukrainian children, and, at home, his repression of the Russian LGBTQ community.

But these crimes have only increased the volume of Pussy Riot members in exile, who use their voices and art to sound further warnings of nationalism on the rise and democracy threatened.

Masha escaped Russia to Lithuania in May 2022 by posing as a food courier, though she hesitates to call it an escape. She says she’s not afraid. She wants to return. She deeply loves her country. She has been imprisoned numerous times, but that doesn’t deter her from her mission, her “actions,” as she calls them, and the Riot Days tour is her way of speaking to “anyone who will see it.”

The tour began on November 1st. in Montreal, where Masha also opened Velvet Terrorism: Pussy Riot’s Russia art exhibition at the Musée d’art Contemporain de Montréal (it runs through March 10, 2024). On stage, Masha was joined by group members Olga Borisova, an ex-policewoman in Russia who quit her job to protest against the regime; Diana Burkot who participated in the Punk Prayer but was never caught; and Alina Petrova, a multi-instrumentalist and co-founder of the Kymatic ensemble. The 22-city Riot Days tour is more than music, it’s a multi-media performance with subtitled video footage of their preparations for “Punk Prayer,” footage of their sham trial, and of their transport to the penal colony. There are photos of Putin embracing the Patriarch, dead bodies in the streets of Bucha, and quotes from the trial.

“I think it’s several missions,” says Masha when asked about the motivation for the tour.

“First, it’s super important to us to bring Riot Days to United States now because we want people to do their own actions and we want to show our story. This story is an example of what can happen if people do not fight for democracy and for freedom. And I believe that stories like this, unfortunately, can happen anywhere. And current news unfortunately proves this. You will have elections next year and I already saw once how easily Donald Trump took the power. And by the way, Donald Trump was the only president during my life who was not covered by Russian propaganda as an enemy. He was super friends, he was super cool, and Russian propaganda is really working in very similar way to Nazi Germany propaganda. I just want to shout it as loud as I can, because I don’t want conservatives, Republicans, or people like Donald Trump to take the power in the United States and help Putin with this crazy wish to rebuild the dead body of Soviet Union, with rockets and tanks and bombs.”

After her initial years in the penal colony and multiple subsequent prison terms, Pussy Riot creator Nadya Tolokonnikova makes art as a “geo-anonymous” person. The Russian Interior Ministry has placed her on its most wanted list.

She travels the world to speak and perform. “This full-scale invasion of Ukraine really put us back many steps as whole human civilization,” she says. “And we see consequences of Putin’s action all around the world today. I don’t think it will stop with just Russia’s war in Ukraine, unfortunately.”

Nadya has seen the impact of Putin on Ukraine firsthand. “When the war in Ukraine started, my first reaction was devastation. I have a lot of friends in Ukraine, comrades, people I love dearly. And I saw streets that I was walking being destroyed and I couldn’t believe my eyes. So first reaction was just crying, as any other normal human being. And then I retreated into action,” she says.

That action was an NFT art piece of the Ukrainian flag which raised $7.1 million to support Ukrainian defense efforts. “That numbed my pain because it showed me that much more people support Ukraine than I thought. They came not just with their word, but actually with their wallet, and it was really awesome to see.”

She also created an art performance and installation called “Putin’s Ashes” where a large photograph of Putin burns after balaclavaed Pussy Riot members push a button for him to be “neutralized.” Bottles of his ‘ashes’ result.

“It’s a metaphor. He has to be stopped,” says Nadya.

“Putin’s Ashes,” by Pussy Riot.

In 2018 Nadya put her experiences into words, as a guide for activism, in a book titled Read & Riot. Reminiscent of Abbie Hoffman’s Steal This Book, Nadya dispenses such wisdom as “be a woman — proud witch and bitch,” and “make your government shit its pants.”

But making one’s government “shit its pants” comes at a cost. In 2018, former Pussy Riot spokesman Pyotr Verzilov was poisoned, but recovered. He had been working with three Russian journalists suspiciously shot and killed in the Central African Republic in July of that year. Today he fights with Ukraine’s armed forces.

Numerous Pussy Riot members have been subjected to house arrest — not allowed to even dispose of their garbage. And two years ago, Pussy Riot members Nika Nikulshina and Sasha Sofeev fled to Georgia. Their crime in Russia? Displaying the Pride flag in Moscow.

“We came up with an action against homophobia,” said Sasha, “and on Putin’s birthday we hung rainbow flags on the main government buildings.” Nika says that this action had cultural resonance. “It’s a lot of bureaucracy in Russia and, you know, Russia is all about flags, banners, things that lalalalala. And we thought about, okay, just one time, it would be cool to make this demonstration for something great. That summer it was the law against LGBTQ. It’s illegal to have marriages. If you’re kissing, if you’re a boy and a boy, you will be beaten up. Even if you’re holding hands. So it’s like super bad. And we were like, okay, that’s what we should hang on the building—not the three color bloody flag.”

Sasha recalls Nika and her placing the rainbow flag on the main FSB building in Moscow’s Lubyanka Square as “one of the most important and happiest moments in my life.”

Sasha says, “Today almost all of us have been forced to leave Russia due to political persecution and false criminal cases. And Russia has been continuing its aggression against Ukraine and its people for almost two years now. In these dark times, the language of action is no longer, for me, capable of changing reality, because the time has come for direct action.

Nika also finds herself stymied. “It’s a bit hard to talk about this. Now I’m in Georgia and I cannot do performances anymore because it’s just my ideological thing that when I have a Russian passport and I’m in foreign land, I cannot do this. Because the action is with performance art. For me it’s totally political and as an artist, you have to put your body in danger. You have to. It’s your sacrifice for art. And here, I will be totally fine, and so that’s just a little bit two-faced for me.” She has switched to film. “I’m making a movie about war in Ukraine,” she says.

Long-time Pussy Rioter Lusine Djanyan has a more personal knowledge of authoritarian terror, having experienced it in her home country of Azerbaijan, where she was a member of the beleaguered Armenian minority before fleeing to Russia in 1988.

When asked about the anti-Armenian atrocities of Azerbaijan President Ilham Aliyev, Lusine replied, “Oh my god, I’m almost crying. You are probably the first journalist who asked me this question.” As an Armenian, Lusine feels invisible, unseen, ignored. Her art seeks to wake people up to the repression, violence, and mass displacement that Azerbaijan’s Amerian minority is subjected to.

Being outspoken about Aliyev and Putin as a member of Pussy Riot had consequences for Lusine and her family. “Our first son was born in Russia and everything changed. Now you have some human being, and you have to protect him. After my husband spent 15 days in prison after one of his actions, secret services came to our home and they threaten me that they will put us both to jail and our son will grow up in some kind of kids’ house and it was absolutely terrifying. I was attacked with my son in the streets. [The secret service] just keep attacking people. You’re playing in a playground and be attacked by secret services. You come home and they follow you. We decided that it’s absolutely impossible to continue like that.”

Today, after a stint as refugees in Russia which her Pussy Riot activities put an end to, Lusine and her family are refugees in Sweden, where Lusine used blankets as canvas for art. “I collected the blankets among my refugee families because a lot of refugees take blankets when you flee. And I took blankets and draw some family portraits. It’s recreating memories, dealing with trauma.”

On stage in Chicago, members of Pussy Riot throw water on the crowd, simulating the cold rain and wilds of the Ural Mountains and the penal colony. It’s meant to shock the senses and spur people to get involved. “There are currently more than 600 political prisoners in Russia,” read the words on the screen before a dozen or so photos of victims flash up. The fight continues a decade after Masha, Nadya, and Kat were part of that statistic.

When asked if she gets discouraged or scared, Masha, without even a pause, replies, “History doesn’t give a fuck about my feelings.”

The Riot Days tour continues through the beginning of December and raises money for the Ohmatdyt, a children’s hospital in Kyiv. More information can be found at riotdays.com.