“Do you sell alcohol in there?”

Sixty-something and confined to an electric mobility scooter, the man asking the question at the will-call window of Ashland, Kentucky’s Paramount Arts Center has seen better days. But he gets the answer he wants.

“Good,” he says, “because, after all, Jesus turned water into wine.”

He’s referring to a well-known incident in the Gospel According to St. John. And, chances are, the 700-or-so other people who have turned out at the Paramount on this Saturday night in July are as familiar with it as he is. But in case they aren’t, the rockers whom they’ve all come to see—Stryper—will soon be flinging pocket-sized New Testaments from the stage, enabling those lucky enough to grab these unlikely pieces of heavy-metal history to read about the miracle for themselves.

“Sometimes it becomes nostalgic,” says Stryper’s frontman, Michael Sweet, 10 days later over an espresso martini at a Boston restaurant, his wife Lisa by his side. “But for us it’s more about getting the Word out there.”

And so it is that, over the last 40 years, a heavy-metal quartet that Jimmy Swaggart denounced as “wolves in sheep’s clothing” has gone on to become the Gideons’ only serious competition where the distribution of free Scriptures is concerned.

Bible tossing isn’t the only thing about Stryper that hasn’t changed since Chris Morris wrote the group up in this publication’s May 1985 (i.e., very first) issue. “[T]hey propel themselves through a set of loud, muscular metal,” Morris wrote, “with fret-mangling guitar interludes and drum solos, all the earmarks of a regular heavy-metal performance.”

And, for the most part, they still do. The drum solos may have gone—Robert Sweet, Michael’s older brother, a whirlwind of energy though he remains, is 63 (the members’ average age)—but, courtesy of Michael and Oz Fox, the fret mangling goes on. As for the volume and the muscle, Michael still belts like Tarzan on steroids. And the band as a whole, shored up by the bass playing and harmony vocals of its newest member, the Firehouse alumnus Perry Richardson, has never sounded fiercer.

And, yes, the guys still perform in the colors that inspired the title of their Enigma Records debut, The Yellow and Black Attack.

The mostly middle-aged faithful at Ashland’s Paramount can’t get enough. Not counting the lone Biker for Christ (back in the day, such bikers comprised the group’s security, turning their shows into a kind of inverse Altamont), two attendees stand out. The first shuffles with a walking stick. With her heavy make-up, powder-blue hair that might be a wig, and glitter-spangled pink robe, she could pass for the Ghost of Halloween Past. Too old to stand, she sits throughout the 90-minute set, filming every second with her smartphone. The other is a girl who’s way too cute to be a minute over 17, lookin’ like a model on the cover of a magazine, the very prototype of the kind of female that teenage boys have been learning the guitar and forming bands to impress ever since the blues had a baby. She stands all night, arms in the air, singing along to hits and deep cuts alike.

“It blows my mind,” says Sweet of the band’s enduring ability to connect with the young. “It really blows my mind.”

The night before Ashland, at the outdoor Ohio Christian-music Alive Festival (where the group went on late and sleep-deprived because of a nine-hour tour-bus breakdown en route), the crowd blew Sweet’s mind even more. “It was majority kids—the younger generation,” he recalls, beaming like a proud dad. “And they were all wearing Stryper shirts.”

Only the Christian-crossover star Lauren Daigle sold more apparel.

“We’ve never sold that kind of stuff at a festival,” says Lisa. “We usually don’t send a lot because nobody ever really does well. But I was, like, ‘Let’s just see what happens.’”

The group hopes to capitalize on such enthusiasm next year, when The Yellow and Black Attack turns 40. “We have a lot planned,” Sweet says. “Like a big year, you know? Lots of touring. We’re doing an acoustic tour. We’re doing an electric tour. We’re gonna do two sets. We’ll do the old classic set in old-style clothing, do an intermission and come back out and do a new set in a new style. We’re gonna really have some fun and do it right.” If all goes well, there’ll be deluxe-edition reissues and an acoustic album too.

A real buzz band… (Photo credit: William Hames)

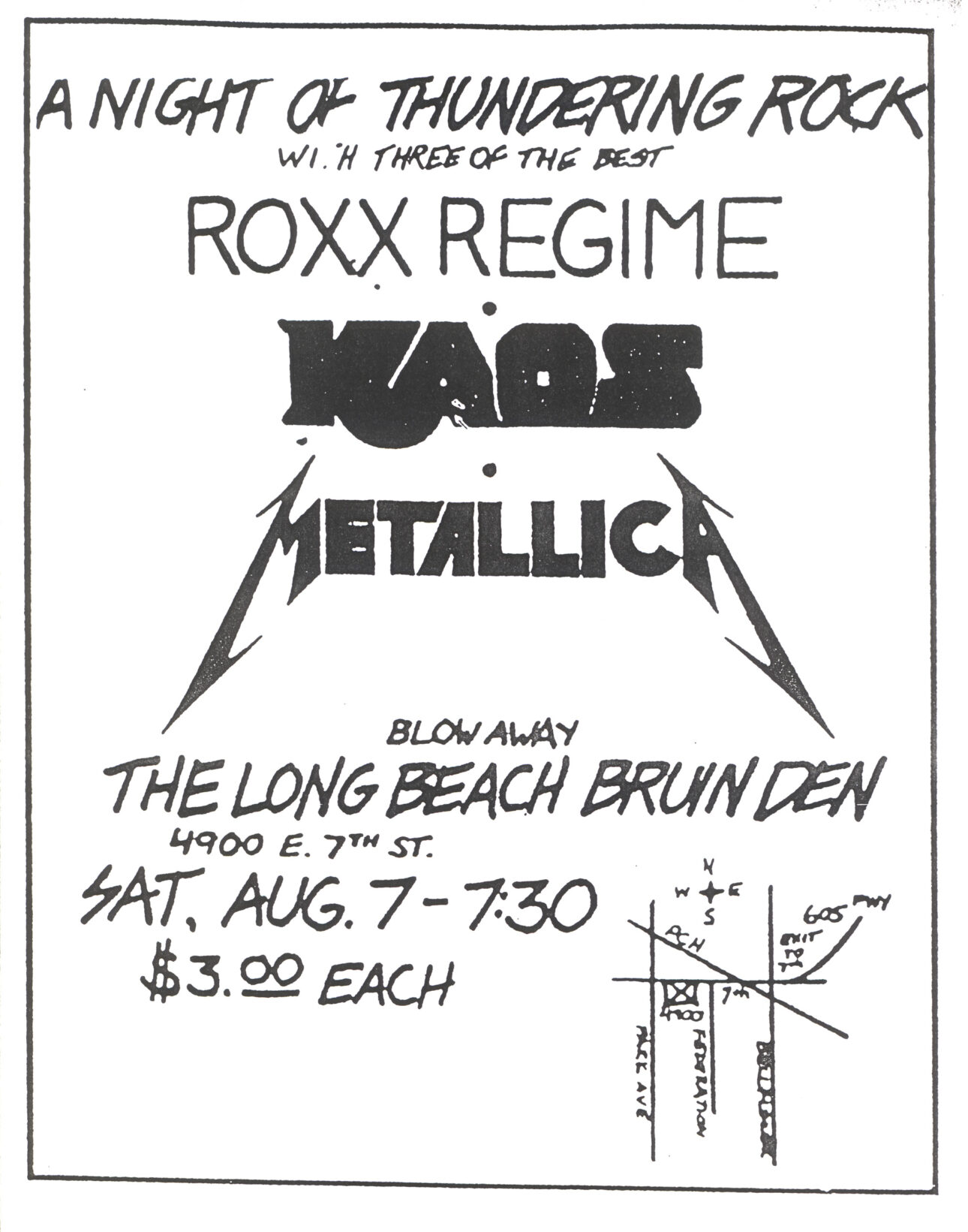

It’s this year, however, that marks the 40th anniversary of the band itself. It was in 1983 that the Sweets, Fox, and their original bassist Tim Gaines abandoned the name under which they’d been performing up and down the Sunset Strip, Roxx Regime, for something more in keeping with their two-toned performance wear and relatively newfound Christian faith. “With his stripes we are healed,” reads Isaiah 53:5, the Bible verse with Messianic overtones that became embedded in their logo.

Not that the line connecting Stryper ’83 to Stryper ’23 has been unbroken or straight. It hasn’t, not by a long shot.

Shortly after Morris’s Spin story appeared, the group released Soldiers Under Command, which like the two that followed (To Hell with the Devil and In God We Trust) went gold and or platinum. In 1987, the power ballad “Honestly” broached the top 30. One year later, the video for “Always There for You”—the song in which Sweet nails a glass-shattering F-sharp an octave or two above middle C—went into heavy rotation on MTV.

The problem was that that clip cost $260,000 of the group’s own money (approximately $685,000 nowadays) and came to represent less about the band or its message and more about their financial extravagance, which would eventually force the group into bankruptcy.

“My mom and my brother were managing the band and controlling the finances,” Sweet recalls. “And I’m not speaking ill of them. I love them. But I should’ve stepped in and said, ‘Wait a minute here. We could do this a lot better.’ We were just spending money. It was crazy!”

There were deeper problems too. During the tour for 1990’s Against the Law, the group, weary of walking its talk, began living it up like the first-tier rock stars they almost were, and what happened on the road didn’t stay on the road. Rumors (mostly true) began to swirl, sending shockwaves through the band’s hypocrisy-intolerant fan base.

Other issues came into play as well, like which members’ compositions ended up getting recorded and therefore which members ended up earning royalties. Of the 48 originals on the group’s first five releases, 37 bore Sweet’s name alone.

And, inevitably, there were “musical differences.” Gaines, for instance, continued performing with the band onstage, but he wasn’t even invited to the sessions for To Hell with the Devil (1986) or In God We Trust (1988). “I took the heat for that,” Sweet says. “In reality though, the whole band made that decision, including the producer.

“I think a lot of people thought maybe Tim wasn’t good enough,” Sweet continues. “But it wasn’t about that. We were after a different style. And he, in our opinion, didn’t play that style as well as we would’ve liked. But he’s a great player, a great singer. It’s just one of those things where in time we realized that, personality-wise—and I think he would tell you the same thing—we were all kind of going in different directions. And when I say ‘all,’ I mean Oz, Rob, and myself—and Tim.”

It would prove to be the rift that keeps on riving.

Disillusioned, Sweet left the band in 1992. Fox, Gaines, and Robert Sweet continued—sometimes as a three-piece, sometimes with the Christian-metal vocalist Dale Thompson—but the writing was on the wall. And what it said was “Stryper is toast.”

During the next 13 years, Sweet experienced solo success (the first of his two albums for the Christian label Benson Records sold 300,000 copies) and failure (by the mid-’90s, no label would touch him). He eventually settled for a decidedly unglamorous $250-a-week job on a cranberry farm owned by the family of his first wife, Kyle. Fox and Gaines, meanwhile, formed the band SinDizzy and released the typically unsubtle He’s Not Dead in 1998.

Stryper reformed off and on, but not until 2005’s Reborn did it seem as if the reunions might take. And even then, Sweet’s 2007-2008 tenure with the post-Brad Delp incarnation of Boston (Sweet officially became “formerly of Boston” in 2011) and Kyle’s cancer diagnosis left the band on uncertain footing.

Kyle passed away in March 2009. In June, Fox married Annie Lobert, the foundress of a ministry called Hookers for Jesus. (It should probably be called Ex-Hookers for Jesus for accuracy’s sake, but how sexy is that?) A month later, the group released Murder by Pride, as unmistakable a statement of renewed purpose as anyone could’ve expected. Somehow, and against many if not all odds, Stryper was back.

They resumed their road-warrior ways, and immediately things got interesting. At one gig, Jackyl’s Jesse James Dupree kicked open the group’s dressing room door, insisting in no uncertain terms that Stryper should be opening for his band and not vice versa. (“A few years later,” Sweet says, “he apologized.”)

And then there was the group’s mini-tour of Nagaland, a landlocked state in east India, the very existence of which ranks high among the world’s best-kept geographical secrets. “Security was a bunch of boys with skirts and spears,” recalls Lisa, laughing.

“[Traveling] in the back of a jeep,” adds Michael. “We did three shows there, and each show was about 6,000 people. It was a tribe. The chief brought us in. It was the most interesting thing we’ve ever done.”

Alas, some of the old problems were back too—like whether Gaines was an essential cog in the wheel or just a replaceable part. It wasn’t until The Covering (razor-sharp hard-rock/heavy-metal covers) in 2011 that he was officially back on board.

He remained aboard for the next six years, performing on 2013’s Second Coming (re-recorded—and better-recorded—Stryper classics) and No More Hell to Pay, 2014’s Live at the Whisky, and 2015’s Fallen.

Then, to make a long and even now not-altogether-clear story short (Christians can be frustratingly discreet), “personal issues” made Gaines bassist non grata. He and the band went back and forth at each other for a while in the press, but in the end he was out and Richardson was in.

When asked if he can imagine a formal burying of the hatchet, if only as a testament to the redemptive power of forgiveness, Sweet says, “If that door ever opens, I’m open to it. In other words, if Tim walked into this restaurant right now, I wouldn’t go to the bathroom or say, ‘Hey, let’s get out of here!’ It wouldn’t be like that. But it hasn’t happened yet.”

Neither has perpetual group contentment over Sweet’s writing the lion’s share of the tunes. “There’s still animosity from time to time, for sure,” Sweet says, “because everyone wants to write. Everyone wants to be a part of it. And I have to be the guy sometimes that says, ‘That song isn’t good enough for the album’ or ‘That song isn’t fitting for the album.’ And then I’m sometimes the bad guy by doing so, you know? But I think that’s the case with any band. We always work through it. We’re still here. It’s not so much of an issue that it causes the band to break up—nothing like that—which it does for a lot of other bands.”

Other aspects of the Stryper situation, on the other hand, are better than ever. Thanks to Lisa, who before working exclusively for Stryper was a successful financial manager for a Massachusetts-based non-profit charity, the band is on the solidest financial footing of its career. (“Everyone can retire,” she says.) With Sweet’s daughter Ellena helping with the accounting and merch tables and Richardson’s wife Shelley coordinating the tours, the band epitomizes the keep-it-in-the-family ethos at its most efficient.

And then there’s the music. From Murder by Pride through last year’s The Final Battle (recording of which began as Fox and Sweet were recovering from brain surgery and detached-retina surgery, respectively), the group has grown from a hair-metal-era curiosity to a well-oiled, crisp, decibel-crushing machine. The guitars scald, the background vocals honor Queen and Sweet (the band), and Michael still hits notes that have to be scraped off the studio ceiling. Subject yourself to any 21st-century Stryper album, and you’ll emerge feeling pummeled. “Take It to the Cross” (obviously, the guys are still on message), from God Damn Evil, could inflict blunt-force trauma.

“We make every album the same way,” Sweet says, explaining the band’s latter-day consistency. “I’ll write the album, send it to the guys. We get together, rehearse. Then we go in, and we record. We know what to do, when to do it, how to do it, and we hope and pray that it’s good.

“I always try to outdo the last one. We just try to make our best album every time. Who’s to say that we can’t? Maybe our best album hasn’t been recorded yet.”

And even if it has, the members’ knack for staying in musical shape with productive moonlighting (Perry and Robert in Cleanbreak, Michael with Dokken’s George Lynch in Sweet & Lynch and L.A. Guns’ Tracii Guns in Sunbomb) guarantees that even their second best will do the Stryper legacy proud.

“We’ve been releasing a lot of stuff,” Sweet says, “between Stryper, myself, side projects, and whatnot. But, speaking for myself, I love to write. I love to create. More than touring. More than all that stuff. I love the studio.”

And although age is creeping up, neither he nor the band show signs of succumbing to decrepitude.

“I look at it this way: I’m alive and I’m breathing, but there’s gonna be a day when I’m not. I simply want to do this for as long as I can before that day comes.”