As you know, all rap is hip-hop, but hip-hop is not only rap. And queer rap (or homo hop) is so much more than just rap artists identifying as LGBTQ. Queer rap is an act of rebellion. It is expression, and it is empowerment, and it certainly is activism.

And that, my friend, is political. As Unique Mical Robinson, a queer rapper and poet from Baltimore, says, “Queer rap is the ultimate act of freedom and liberation.”

As a gay white boy growing up in Apartheid South Africa (circa 1990s), rap music came from a few wellsprings. Firstly, my many ventures up to Europe, where I would hang at Virgin Records in London (wearing Nike Max pumped-up kicks, needless to say) into the late hours of the night, buying as many CDs as my little hands could carry. Or to Berlin, where I would slip out of the parents’ hotel and find a club I was far too young to get into, just to listen to music that I had never heard before. Like German hip-hop pioneers Advanced Chemistry, who even rapped in English — but, alas, were very much not gay.

There was also a giant warehouse in Johannesburg called CD Warehouse (started by a Mozambican Jewish couple who smuggled CDs into the country during sanction days). They sold rap, and I would sit in the listening booths with a secret flask of whiskey, listening to everything the front desk human would recommend, hours and hours poured into this love. That’s when I was introduced to Kwaito, a sort of new genre based on house music which developed in South Africa in the 1990s, filled with various rap elements.

I bopped my head along with this like the happy tyke I was. And my friends visiting from abroad thought we were the cool kids as they’d never even heard this sound. This was all pre-Die Antwoord (a problematic rap-rave duo that took the country by storm with their uniquely South African zef style) and also pre-Afrikaans boy rapper Jack Parow. Both became more well known as the Internet propelled them in the 2000s.

And then there was the trusty radio. A local Pretoria campus radio station, TUKS 107.2 FM, was always in everyone’s car. They mostly played local bands, like Just Jinger and the Springbok Nude Girls, that sounded far too “rock” to my suave ears. I wanted more. I wanted something more subversive, something anti-Apartheid, and naturally, unputdownable. I wanted something queer. And I hunted that down. So I found Johannesburg-born YFM, and they played rap from eyes open to eyes shut.

It was the late ‘90s, and it was the golden age of hip-hop. To me, most of my desires were being fulfilled by Lauryn Hill and Missy Elliott. They were my superheroes. They rapped in a way that twisted my tongue. I listened to them on my Discman and learnt every word. But I wondered why the radio –- and every house party I went to — played mostly male rappers. Straight male rappers, I should tack on. Tupac, Busta Rhymes, Enimem, and 50 Cent were constants. But where were my people, ones I could identify with a little more?

In the book Queer Voices in Hip-Hop, Lauron J. Kehrer argues that hip-hop authenticity relies on a construction of the rapper as a “Black, masculine, heterosexual, cisgender man who enacts a narrative of struggle and success.” Well, let’s be clear: I could appreciate this as music, but I couldn’t see myself in any of that.

But it’s probably useful to venture into the past to understand how we managed to get from a genre that was historically one of the least queer-friendly genres of music (with ugly homophobic views and anti-gay lyrics) to Lil Nas X rapping in ways that turn my heart custard. Afterall, the history of queer rap is intertwined with the history of hip-hop itself. And as Kehrer reminds us, “openly queer and trans rappers not as anomalies or newly emerging phenomena but as musicians within a long-standing Black queer musical lineage.”

But please let’s not skip over Lil Nas X’s sexy boy lyrics — “Oh, call me by your name (mmm, mmm, mmm) / Tell me you love me in private.”

Queer rappers were at the birth of hip-hop in the late ‘70s. Hip-hop came from disco, and you know who was on the forefront of disco? The queer community plus some well-known queer DJs like Frankie Knuckles, and Larry Levan. And then hip-hop went mainstream, where it morphed into something more heteronormative and unfortunately homophobic. Queer rappers of the time had to hide their sexuality or face discrimination or even violence.

But, nevertheless, they persisted. In cities like New York, the 1990s was home to “homohop,” where artists rapped about their genders, sexualities, and also the politics of it all. Some of the pioneers of this movement include Rainbow Flava, Hanifah Walidah, Deep Dickollective (D/DC), Medusa, Tori Fixx, Deadlee, Katastrophe, and God-Des and She. Madonna was, of course, friendly with many of them, hiring them, collaborating with them, and championing their creativity.

And this is exactly how queer rap started to find its foothold. Queer rappers were creating community — yes, Madonna helped a little on the sides –- and gathering their uber fans. Whether it was Mykki Blanco, Zebra Katz, Cakes da Killa, or Le1f, all who have been releasing albums and mixtapes since 2012, the scene was shifting. Rap was debating in its lyrics issues that queer people deal with, from sex and sexuality, to equality, to sharing their love stories and struggles. Some themes were universal, and others uniquely queer (like rapping about PrEP, the HIV drug, or discovering your attraction to the same gender, or the anxiety of the world not accepting you, etc.). And yes, today Big Freedia (the Queen of Bounce) is continuing this tradition as she takes her New Orleans sound to celebrate queerness and collaborates with Beyonce, Lizzo, and Drake.

And this is how queer rap ends up on everyone’s plate.

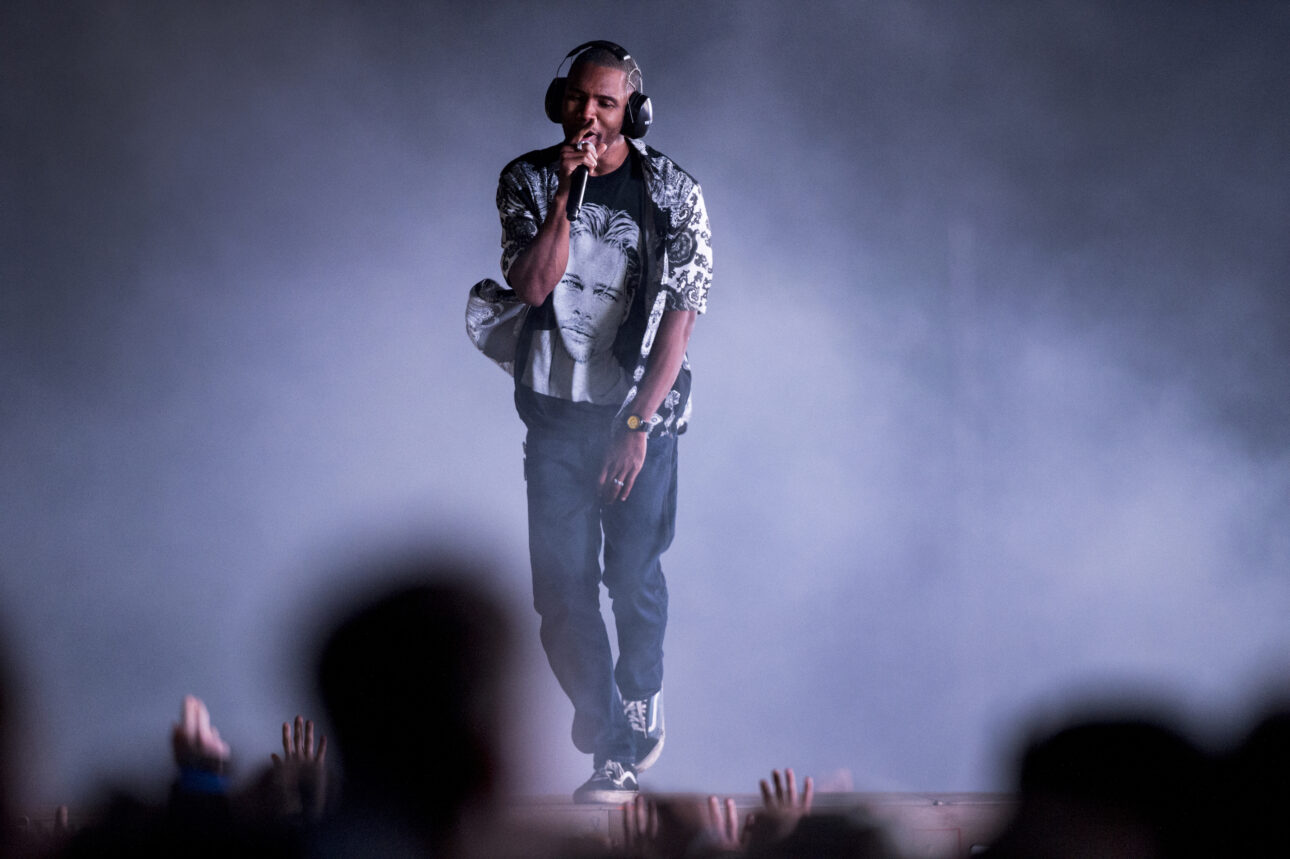

But Frank Ocean, who wrote in a 2012 blog post that his first love was a man, has become a pioneer of the queer rap movement. Even when an old-school rapper like Snoop Dogg said, “Frank Ocean ain’t no rapper. He’s a singer. It’s acceptable in the singing world, but in the rap world I don’t know if it will ever be acceptable because rap is so masculine,” it didn’t stop Ocean from shining his star. (When asked by GQ if he’s bi-sexual, he responded, in part, “You can move to the next question. I’ll respectfully say that life is dynamic and comes along with dynamic experiences, and the same sentiment that I have towards genres of music, I have towards a lot of labels and boxes and shit.”) Since sharing his story, Ocean has used his music, complete with those introspective and cryptic lyrics, as a platform to raise awareness and funds for all kinds of queer causes. Plus, he pulled in some Grammy Awards en route.

I like to think that Ocean showed up and revealed that, yes, there is a door, and it’s for whomever would like to use it. Lil Nas X ignored the door and did a base jump into the world of rap music.

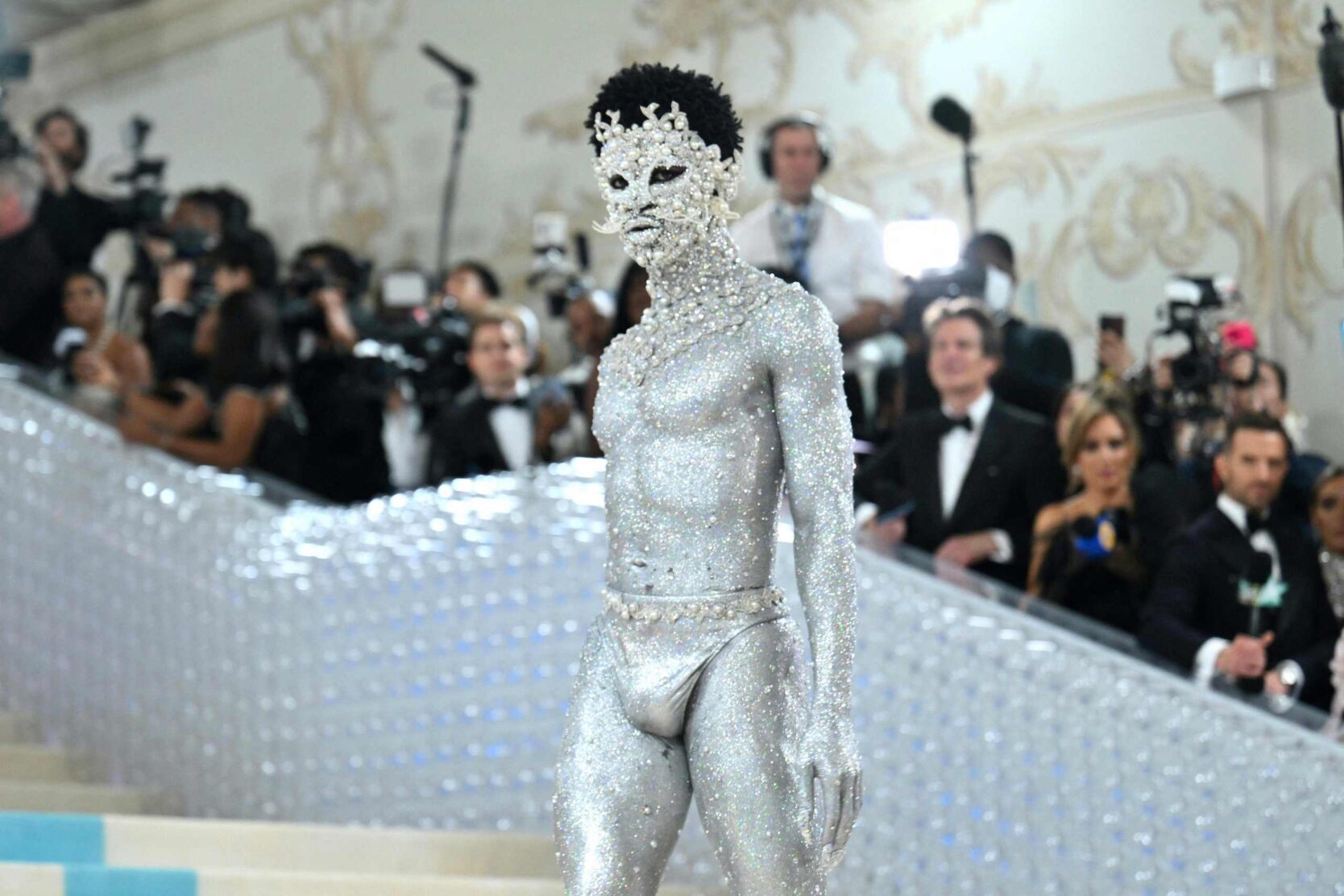

Internet-born Lil Nas X took rap (or pop-rap, depending on how you see the world) and turned it as queer as humanly possible. A young artist out of small-town Georgia, he brought an overt gayness to the genre that had never been there — leaning into lyrics and imagery that queer rappers perhaps alluded to previously, or included but then lost out on commercial success. He battled homophobia, self-acceptance in a “not always so queer-friendly” world, and leaned into what queer love could mean. Lil Nas X did it all and won every worthy music award, broke the charts, and gave male Satan a sexy lap dance in one of his music videos.

The very definition of queer rap suddenly expanded — challenging these old ideas of hypermasculinity, heteronormativity, and misogyny. “And we’re seeing how music is now the forefront of all this queerness — queer artists are now no longer just the makeup and hair behind-the-scenes teams,” shares Unique.

With a genre so male-dominated, it was also ready for a queer woman to come in and shake things up. Young M.A did exactly that. Asserting her sexuality, she had a breakthrough viral single “OOOUUU” raising visibility for lesbian rappers to join the party. (In 2019, when asked if she’s a lesbian, Young M.A told Hollywood Unlocked, “We don’t do no labels. I just wouldn’t date a guy.”) And some of the early icons were Da Brat and Queen Latifah, both of whom didn’t have the opportunities to fully come out as queer to the world. “Queer artists in general are no less talented than our straight counterparts, but we’re often undervalued and underrepresented,” adds Unique. “But the Internet has helped with some of this acceptance, and is adding to the democratizing of the music world. You’re able to build an audience and your image — however you wish.”

And even the full-on industry is shifting. It has been historically hostile and dismissive of queer rappers, often ignoring or marginalizing their contributions or subjecting them to ridicule or violence.

And as Baltimore rapper DDM (who started out doing rap battles in the early 2010s) adds, “It was a small network of us underground across the country. We all knew or knew of each other. It was tough in those years because record labels didn’t see the money in signing queer artists at that time, so we had to make it work.”

With the current rise of queer culture in all of popular culture, there is a feeling of unstoppability. This tide, oh, she’s-a-shifting. The industry has become more accepting and supportive of queer rappers, recognizing their talent and influence. For example, Kevin Abstract has gained critical acclaim and commercial success as the leader of the rap collective Brockhampton, dubbed as “the Internet’s first boy band.”

Just look at some of the magic happening in the fabulous city of Baltimore, where more and more queer rappers are making their mark — like, some of my now favorites Dapper Dan Midas (AKA DDM), Kotic Couture, and RoVo Monty.

Kotic Couture, dubbed “Queen of the Underground,” shared that she’s seeing how Baltimore specifically is letting the club scene expand. Her sound combines elements of club music, rap, every variance of hip-hop, and even ballroom. “Right now queer rap is expansive, and the sound isn’t getting pigeon-holed. We’re making it all up as we go, with no rules.” And this is evident in clubs like The Crown, in North Baltimore, where they’re switching up the music all the time from rap, to anime, to psychedelic, and ska-fused indie punk all the way to reggaeton. “Tik Tok has helped spread this –- especially at home during COVID –- and now everyone wants to get out again, and the underground is where the action is at,” adds Couture.

Well, then, where is queer rap going next? Unique thinks that it is simply going where society is going. And that is leading us to more visibility. “The backlash and the politicians think it will make us afraid, like what they are doing in Florida with the ‘don’t say gay’ bills. But it will do just the opposite,” says Unique. “The oppression won’t work. More kids will come out in whatever variance they want. And the representation for queer folks will just be everywhere, so much so that more kids can see themselves in these artists. And it is rap that is pushing all of this forward. This is a place where you don’t have to run and hide. Because we are done with that.”